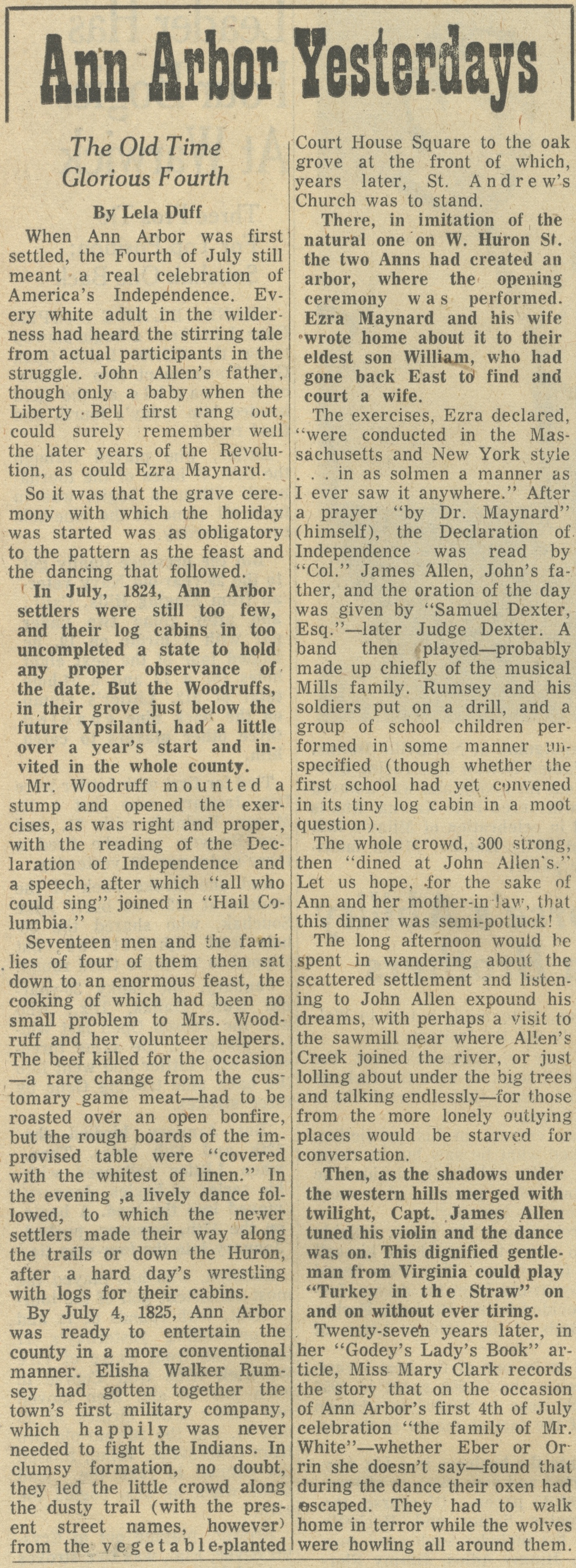

Ann Arbor Yesterdays ~ The Old Time Glorious Fourth

Ann Arbor Yesterdays

The Old Time Glorious Fourth

By Lela Duff

When Ann Arbor was first settled, the Fourth of July still meant a real celebration of America’s Independence. Every white adult in the wilderness had heard the stirring tale from actual participants in the struggle. John Allen’s father, though only a baby when the Liberty Bell first rang out, could surely remember well the later years of the Revolution, as could Ezra Maynard.

So it was that the grave ceremony with which the holiday was started was as obligatory to the pattern as the feast and the dancing that followed.

In July, 1824, Ann Arbor settlers were still too few, and their log cabins in too uncompleted a state to hold any proper observance of the date. But the Woodruffs, in their grove just below the future Ypsilanti, had a little over a year’s start and invited in the whole county.

Mr. Woodruff mounted a stump and opened the exercises, as was right and proper, with the reading of the Declaration of Independence and a speech, after which “all who could sing” joined in “Hail Columbia.”

Seventeen men and the families of four of them then sat down to an enormous feast, the cooking of which had been no small problem to Mrs. Woodruff and her volunteer helpers. The beef killed for the occasion —a rare change from the customary game meat—had to be roasted over an open bonfire, but the rough boards of the improvised table were “covered with the whitest of linen.” In the evening, a lively dance followed, to which the newer settlers made their way along the trails or down the Huron, after a hard day’s wrestling with logs for their cabins.

By July 4, 1825, Ann Arbor was ready to entertain the county in a more conventional manner. Elisha Walker Rumsey had gotten together the town’s first military company, which happily was never needed to fight the Indians. In clumsy formation, no doubt, they led the little crowd along the dusty trail (with the present street names, however from the vegetable-planted Court House Square to the oak grove at the front of which, years later, St. Andrew's Church was to stand.

There, in imitation of the natural one on W. Huron St. the two Anns had created an arbor, where the opening ceremony was performed. Ezra Maynard and his wife wrote home about it to their eldest son William, who had gone back East to find and court a wife.

The exercises, Ezra declared, "were conducted in the Massachusetts and New York style ... in as solemn a manner as I ever saw it anywhere.” After a prayer “by Dr. Maynard” (himself), the Declaration of Independence was read by "Col.” James Allen, John’s father, and the oration of the day was given by “Samuel Dexter, Esq.’’—later Judge Dexter. A band then played—probably made up chiefly of the musical Mills family. Rumsey and his soldiers put on a drill, and a group of school children performed in some manner unspecified (though whether the first school had yet convened in its tiny log cabin in a moot question).

The whole crowd, 300 strong, then “dined at John Allen's." Let us hope, for the sake of Ann and her mother-in law, that this dinner was semi-potluck!

The long afternoon would be spent in wandering about the scattered settlement and listening to John Allen expound his dreams, with perhaps a visit to the sawmill near where Allen’s Creek joined the river, or just lolling about under the big trees and talking endlessly—for those from the more lonely outlying places would be starved for conversation.

Then, as the shadows under the western hills merged with twilight, Capt. James Allen tuned his violin and the dance was on. This dignified gentleman from Virginia could play “Turkey in the Straw” on and on without ever tiring.

Twenty-seven years later, in her “Godey’s Lady’s Book” article, Miss Mary Clark records the story that on the occasion of Ann Arbor’s first 4th of July celebration "the family of Mr. White”—whether Eber or Orrin she doesn’t say—found that during the dance their oxen had escaped. They had to walk home in terror while the wolves were howling all around them.