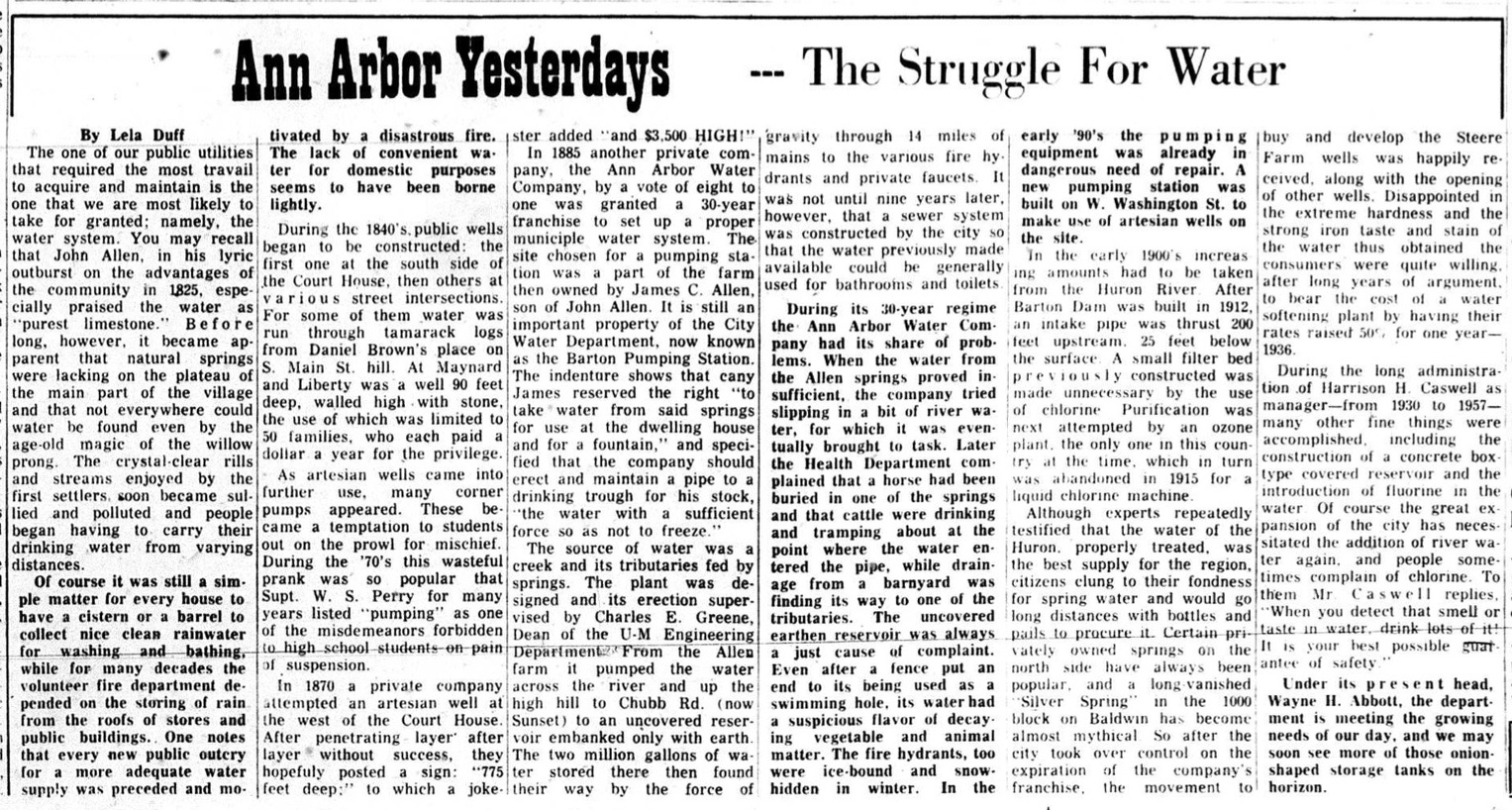

Ann Arbor Yesterdays ~ The Struggle For Water

Ann Arbor Yesterdays — The Struggle For Water

September 19, 1960

By Lela Duff

The one of our public utilities that required the most travail to acquire and maintain is the one that we are most likely to take for granted; namely, the water system. You may recall that John Allen, in his lyric outburst on the advantages of the community in 1825, especially praised the water as "purest limestone." Before long, however, it became apparent that natural springs were lacking on the plateau of the main part of the village and that not everywhere could water be found even by the age-old magic of the willow prong. The crystal-clear rills and streams enjoyed by the first settlers, soon became sullied and polluted and people I began having to carry their drinking water from varying distances.

Of course it was still a simple matter for every house to have a cistern or a barrel to collect nice clean rainwater for washing and bathing, while for many decades the volunteer fire department depended on the storing of rain from the roofs of stores and public buildings. One notes I that every new public outcry for a more adequate water supply was preceded and motivated by a disastrous fire. The lack of convenient water for domestic purposes seems to have been borne lightly.

During the 1840's public wells began to be constructed: the first one at the south side of the Court House, then others at various street intersections. For some of them water was run through tamarack logs from Daniel Brown's place on S. Main St. hill. At Maynard and Liberty was a well 90 feet deep, walled high with stone, the use of which was limited to 50 families, who each paid a dollar a year for the privilege.

As artesian wells came into further use, many corner pumps appeared. These became a temptation to students out on the prowl for mischief. During the '70’s this wasteful prank was so popular that Supt. W. S. Perry for many years listed "pumping” as one of the misdemeanors forbidden to high school students on pain of suspension.

In 1870 a private company attempted an artesian well at the west of the Court House. After penetrating layer after layer without success, they hopefully posted a sign: “775 feet deep:” to which a jokester added "and $3,500 HIGH!”

In 1885 another private company, the Ann Arbor Water Company, by a vote of eight to one was granted a 30-year franchise to set up a proper municipal water system. The site chosen for a pumping station was a part of the farm then owned by James C. Allen, son of John Allen. It is still an important property of the City Water Department, now known as the Barton Pumping Station. The indenture shows that canny James reserved the right "to take water from said springs for use at the dwelling house and for a fountain," and specified that the company should erect and maintain a pipe to a drinking trough for his stock, "the water with a sufficient force so as not to freeze."

The source of water was a creek and its tributaries fed by springs. The plant was designed and its erection supervised by Charles E. Greene, Dean of the U-M Engineering Department. From the Allen farm it pumped the water across the river and up the high hill to Chubb Rd. (now Sunset) to an uncovered reservoir embanked only with earth. The two million gallons of water stored there then found their way by the force of gravity through 14 miles of mains to the various fire hydrants and private faucets. It was not until nine years later, however, that a sewer system was constructed by the city so that the water previously made available could be generally used for bathrooms and toilets

During its 30-year regime the Ann Arbor Water Company had its share of problems. When the water from the Allen springs proved in sufficient, the company tried slipping in a bit of river water for which if was eventually brought to task. Later the Health Department complained that a horse had been buried in one of the springs and that cattle were drinking and tramping about at the point where the water entered the pipe, while drainage from a barnyard was finding its way to one of the tributaries. The uncovered earthen reservoir was always a just cause of complaint. Even after a fence put an end to its being used as a swimming hole, its water had a suspicious flavor of decaying vegetable and animal matter. The fire hydrants, too were icebound and snow-hidden in winter. In the early '90’s the pumping equipment was already in dangerous need of repair. A new pumping station was built on W. Washington St. to make use of artesian wells on the site.

In the early 1900s increasing amounts had to be taken from the Huron River. After Barton Dam was built in 1912, an intake pipe was thrust 200 led upstream, 25 feet below the surface. A small filter bed p r e v i o u s I y constructed was made unnecessary by the use of chlorine. Purification was next attempted by an ozone plant, the only one in this country at the time, which in turn was abandoned in 1915 for a liquid chlorine machine.

Although experts repeatedly testified that the water of the Huron, properly treated, was the best supply for the region, citizens clung to their fondness for spring water and would go long distances with bottles and pails to procure it. Certain privately owned springs on the north side have always been popular, and a long vanished Silver Spring in the 1000 block on Baldwin has become almost mythical. So after the city took over control on the expiration of the company's franchise, the movement to buy and develop the Steere Farm wells was happily received, along with the opening of other wells. Disappointed in the extreme hardness and the strong iron taste and stain of the water thus obtained, the consumers were quite willing, after long years of argument, to bear the cost of a water softening plant by having their rates raised 50¢ for one year — 1936.

During the long administration of Harrison H. Caswell as manager—from 1930 to 1957— many other fine things were accomplished, including the construction of a concrete box type covered reservoir and the introduction of fluorine in the water. Of course the great expansion of the city has necessitated the addition of river water again, and people sometimes complain of chlorine. To them Mr. Caswell replies, "When you detect that smell or the taste in water, drink lots of it! It is your best possible guarantee of safety."

Under its present head, Wayne H. Abbott, the department is meeting the growing needs of our day and we may soon see more of those onion-shaped storage tanks on the horizon.

Article

Subjects

Lela Duff

Ann Arbor Yesterdays

Local History

Water Supply

Public Utilities

Water Wells

Ann Arbor Water Company

Barton Pumping Station

University of Michigan - Faculty & Staff

Public Health

Huron River

Barton Dam

Old News

Ann Arbor News

John Allen

Daniel Brown

W. S. Perry

James C. Allen

Charles E. Greene

Harrison H. Caswell

Wayne H. Abbott