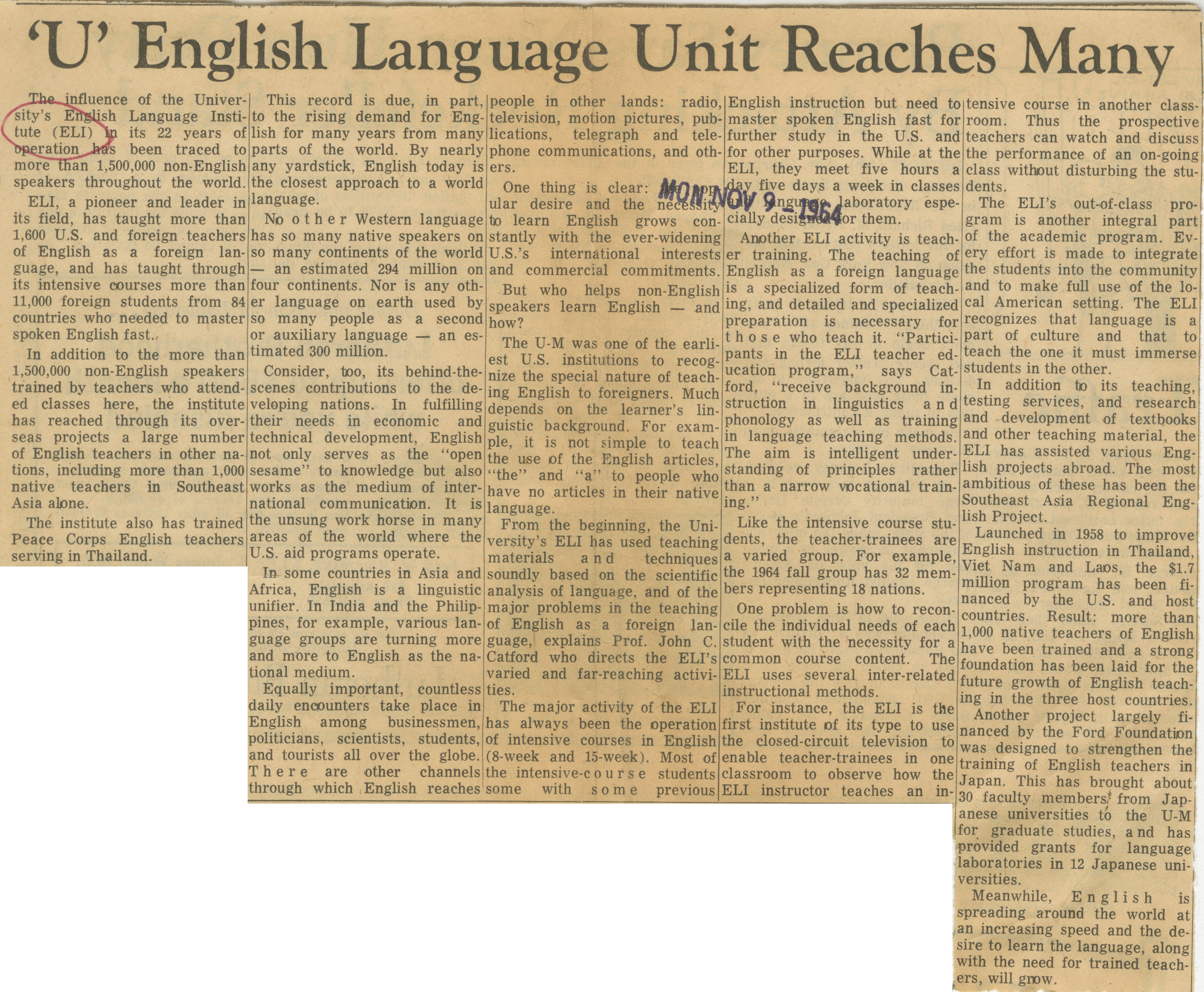

'U' English Language Unit Reaches Many

‘U' English Language Unit Reaches Many

The influence of the University's English Language Institute (ELI) in its 22 years of operation has been traced to more than 1,500,000 non-English speakers throughout the world.

ELI, a pioneer and leader in its field, has taught more than 1,600 U.S. and foreign teachers of English as a foreign language, and has taught through its intensive courses more than 11,000 foreign students from 84 countries who needed to master spoken English fast.

In addition to the more than 1,500,000 non-English speakers trained by teachers who attended classes here, the institute has reached through its overseas projects a large number of English teachers in other nations, including more than 1,000 native teachers in Southeast Asia alone.

The institute also has trained Peace Corps English teachers serving in Thailand.

This record is due, in part, to the rising demand for English for many years from many parts of the world. By nearly any yardstick, English today is the closest approach to a world language.

No other Western language has so many native speakers on so many continents of the world — an estimated 294 million on four continents. Nor is any other language on earth used by so many people as a second or auxiliary language — an estimated 300 million.

Consider, too, its behind-the-scenes contributions to the developing nations. In fulfilling their needs in economic and technical development, English not only serves as the “open sesame” to knowledge but also works as the medium of international communication. It is the unsung work horse in many areas of the world where the U.S. aid programs operate.

In some countries in Asia and Africa, English is a linguistic unifier. In India and the Philippines, for example, various language groups are turning more and more to English as the national medium.

Equally important, countless daily encounters take place in English among businessmen, politicians, scientists, students, and tourists all over the globe. There are other channels through which English reaches people in other lands: radio, television, motion pictures, publications, telegraph and telephone communications, and others.

One thing is clear: the popular desire and the necessity to learn English grows constantly with the ever-widening U.S.’s international interests and commercial commitments.

But who helps non-English speakers learn English — and how?

The U-M was one of the earliest U.S. institutions to recognize the special nature of teaching English to foreigners. Much depends on the learner’s linguistic background. For example, it is not simple to teach the use of the English articles, “the” and “a” to people who have no articles in their native language.

From the beginning, the University’s ELI has used teaching materials and techniques soundly based on the scientific analysis of language, and of the major problems in the teaching of English as a foreign language, explains Prof. John C. Catford who directs the ELI’s varied and far-reaching activities.

The major activity of the ELI has always been the operation of intensive courses in English (8-week and 15-week). Most of the intensive-course students some with some previous English instruction but need to master spoken English fast for further study in the U.S. and for other purposes. While at the ELI, they meet five hours a five days a week in classes and language laboratory especially designed for them.

Another ELI activity is teacher training. The teaching of English as a foreign language is a specialized form of teaching, and detailed and specialized preparation is necessary for those who teach it. “Participants in the ELI teacher education program,” says Cat-ford, “receive background instruction in linguistics and phonology as well as training in language teaching methods. The aim is intelligent understanding of principles rather than a narrow vocational training.”

Like the intensive course students, the teacher-trainees are a varied group. For example, the 1964 fall group has 32 members representing 18 nations.

One problem is how to reconcile the individual needs of each student with the necessity for a common course content. The ELI uses several inter-related instructional methods.

For instance, the ELI is the first institute of its type to use the closed-circuit television to enable teacher-trainees in one classroom to observe how the ELI instructor teaches an intensive course in another classroom. Thus the prospective teachers can watch and discuss the performance of an on-going class without disturbing the students.

The ELI’s out-of-class program is another integral part of the academic program. Every effort is made to integrate the students into the community and to make full use of the local American setting. The ELI recognizes that language is a part of culture and that to teach the one it must immerse students in the other.

In addition to its teaching, testing services, and research and development of textbooks and other teaching material, the ELI has assisted various English projects abroad. The most ambitious of these has been the Southeast Asia Regional English Project.

Launched in 1958 to improve English instruction in Thailand, Viet Nam and Laos, the $1.7 million program has been financed by the U.S. and host countries. Result: more than 1,000 native teachers of English have been trained and a strong foundation has been laid for the future growth of English teaching in the three host countries.

Another project largely financed by the Ford Foundation was designed to strengthen the training of English teachers in Japan. This has brought about 30 faculty members) from Japanese universities to the U-M for graduate studies, and has provided grants for language laboratories in 12 Japanese universities.

Meanwhile, English is spreading around the world at an increasing speed and the desire to learn the language, along with the need for trained teachers, will grow.