Greatest Of All -- 'Sparks'

George Wedemeyer has seen many electronic advances during his long career. But his fondest memories go back decades when he was "sparks" on an ocean-going freighter.

__ City/Comfy/Region _

Page

3

The Ann Arbor News Saturday, October 29, 1977

Greatest Of All—'Sparks'

By William B. Trend

George Wedemeyer is living proof that dreams do come true.

If you're willing to work for them.

In pre-World War I days American youngsters dreamed of becoming cowboys or major league baseball players or aviators. Young George Wedemeyer had none of those dreams. He had only one thing in mind: he wanted to be a "sparks" — a wireless radio operator on an ocean-going ship.

His ambition did not come from reading books or seeing pictures of wireless operators toiling away at the blue sparks of the wireless transmitter. He had seen, close up, professional “sparks” aboard real ships.

William Wedemeyer. George’s father, was a U.S. congressman in the days immediately preceding World War I. At that time Rep. Wedemeyer was on a congressional commission appointed to oversee the operation of the relatively new Panama Canal. As a member of the commission the senior Wedemeyer was sent to the Canal on an inspection tour. He took his son, George, with him.

THE OCEAN VOYAGE took a week each way and young Wedemeyer became fascinated by the crashing blue sparks emitted from the wireless transmitter aboard the ship.

"I made a pest of myself, asking the operators endless questions about the wireless." he laughs today. "But maybe because my father was a congressman the operators were patient and answered everything I asked. I was amazed and awed by their profession. And I vowed some day I would become a "sparks."

As if to test young Wedemeyer’s youthful hope, fate sent a two-day hurricane his way on the way back from Panama. The winds at one point hit 110 miles an hour. All the ship's life boats were torn from their moorings and landed in the raging sea. The wireless aerial was yanked free by the screaming winds and the ship itself received substantial damage.

"I was terror-stricken," Wedemeyer admits. "I was sure I would never see home again."

BUT THE SHIP, virtually given up for lost, finally cruised into port three days late.

"We had beaten the sea." Wedemeyer recalls. "And rather than scaring me on I knew I had to go back again. I had sea fever."

Before he entered his teens. George Wedemeyer had his first "ham" wireless and by his 17th birthday he had earned his first class commercial license. The U.S. Secretary of Commerce who signed Wedcmeyer’s license was Herbert Hoover.

Even though he had not yet finished high school, young George signed on as a wireless man on a new U.S. Shipping Board freighter, the Pulaski, leaving Toledo. Ohio for the east coast and points south

The crew addressed the youngster as "Sparks" and his position permitted him to cal with the ship's officers.

"It was just about too wonderful to believe." Wedemeyer recalls today. "Here I was a certified wireless operator aboard a ship! And they were paying me $125 a month besides!"

THE TEEN-AGED Wedemeyer remained aboard the Pulaski as the "sparks" until the day on the east coast that a harbormaster officer appeared with orders for the youth to go ashore.

"My mother wanted me home to finish high school, it was as simple as that!" Wedemeyer chuckles. "And, with some regret. I went.''

Back he came to Ann Arbor High School to finish his schooling and later go on to electrical engineering studies at the University of Michigan and the University of Virginia.

Later he would return to the sea as the "sparks" on various freighters plying the Atlantic coast. Eventually he returned to Ann Arbor where his radio knowledge led him to help operate the city's first commercial radio station. It was called "WQAJ" and operated from the top floor of the former YMCA building on N. Fourth Avenue.

One of the sponsored programs was a "music memory contest" paid for by the Ann Arbor Daily Times-News as a promotion gimmick. Later he designed one of the early radio models. the "Arborphone". an instrument which was .built by an Ann Arbor company.

STILL LATER Wedemeyer landed a job as designer-serviceman for a Monroe radio* company which manufactured and sold a model called the "Monrona." It was working for that firm that Wedemeyer was sent on a service call to what turned out to be a bootlegger's hideout. He was greeted by drawn guns held by racketeer guards but after identifying himself was allowed inside where he repaired the radio.

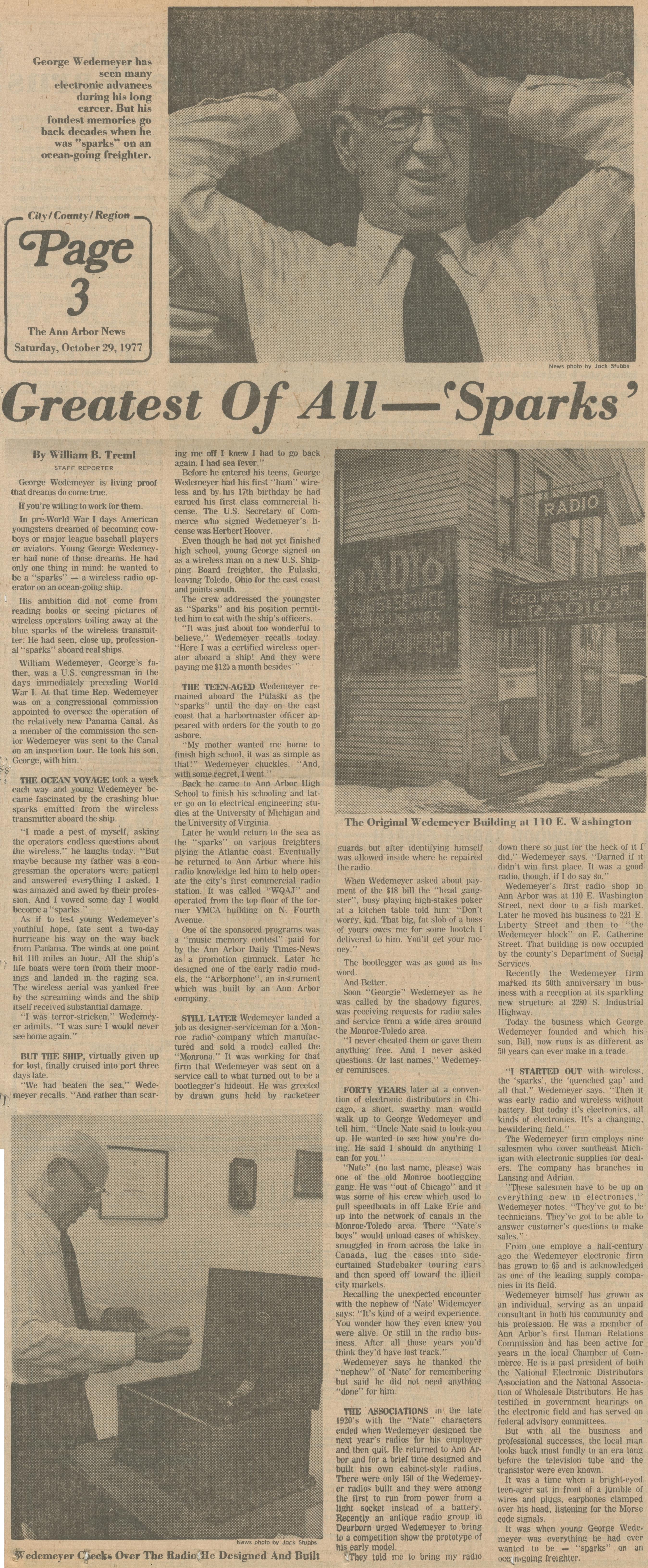

Wedemeyer Checks Over The Radio He Designed And Built

When Wedemeyer asked about payment of the $18 bill the "head gangster," busy playing high-stakes poker at a kitchen table told him: “Don't worry, kid. That big. fat slob of a boss of yours owes me for some hootch I delivered to him. You'll get your money."

The bootlegger was as good as his

And Better.

Soon "Georgie" Wedemeyer as he was called by the shadowy figures, was receiving requests for radio sales and service from a wide area around the Monroe-Toledo area.

"I never cheated them or gave them anything free. And I never asked questions. Or last names," Wedemeyer reminisces.

FORTY YEARS later at a convention of electronic distributors in Chicago, a short, swarthy man would walk up to George Wedemeyer and tell him. "Uncle Nate said to look-you up. He wanted to see how you're doing. He said I should do anything I can for you."

"Nate" (no last name, please) was one of the old Monroe bootlegging gang. He was “out of Chicago" and it was some of his crew which used to pull speedboats in off Lake Erie and Monroe-Toledo area. There “Nate’s boys" would unload cases of whiskey, smuggled in from across the lake in Canada, lug the cases into side-curtained Studebaker touring ears and then speed off toward the illicit city markets.

Recalling the unexpected encounter with the nephew of 'Nate' Widemeyer says: "It's kind of a weird experience. You wonder how they even knew you were alive. Or still in the radio business. After all those years you'd think they'd have lost track."

Wedemeyer says he thanked the "nephew" of 'Nate' for remembering but said he did not need anything "done” for him.

THE ASSOCIATIONS in the late 1920's with the “Nate" characters ended when Wedemeyer designed the next year’s radios for his employer and then quit. He returned to Ann Arbor and for a brief time designed and built his own cabinet-style radios. There were only 50 of the Wedemeyer radios built and they were among the first to run from power from a light socket instead of a battery. Recently an antique radio group in Dearborn urged Wedemeyer to bring to a competition show the prototype of his early model.

They told me to brig my radio down there so just for the heck of it I did." Wedemeyer says. “Darned if it didn't win first place. It was a good radio, though, if I do say so."

Wedemeyer's first radio shop in

Ann Arbor was at 110 E. Washington Street, next door to a fish market. Later he moved his business to 221 E. Liberty Street and then to "the Wedemeyer block" on E. Catherine Street. That building is now occupied by the county's Department of Social Services.

Recently the Wedemeyer firm marked its 50th anniversary in business with a reception at its sparkling new structure at 2280 S. Industrial Highway.

Today the business which George Wedemeyer founded and which his son. BUI, now runs is as different as 50 years can ever make in a trade.

"I STARTED OUT with wireless, the 'sparks', the 'quenched gap' and all that." Wedemeyer says. "Then it was early radio and wireless without battery. But today it's electronics, all kinds of electronics. It's a changing, bewildering field."

The Wedemeyer firm employs nine salesmen who cover southeast Michigan with electronic supplies for dealers. The company has branches in Lansing and Adrian.

"These salesmen have to be up on everything new in electronics," Wedemeyer notes. "They've got to be technicians. They've got to be able to answer customer's questions to make sales."

From one employee a half-century ago the Wedemeyer electronic firm has grown to 65 and is acknowledged as one of the leading supply companies in its field.

Wedemeyer himself has grown as an individual, serving as an unpaid consultant in both his community and his profession. He was a member of Ann Arbor’s first Human Relations Commission and has been active for years in the local Chamber of Commerce. He Is a past president of both the National Electronic Distributors Association and the National Association of Wholesale Distributors. He has testified in government hearings on the electronic field and has served on federal advisory committees.

But with all the business and professional successes, the local man looks back most fondly to an era long before the television tube and the transistor were even known.

It was a time when a bright-eyed teen-ager sat in front of a jumble of wires and plugs, earphones clamped over his head, listening for the Morse code signals.

It was when young George Wedemeyer was everything he had ever wanted to be — "sparks" on an ocean-going freighter.

Article

Subjects

William B. Treml

WQAJ Radio

Wedemeyer Electronc Supply Co.

United States House of Representatives

Radios

Radio Stations

Electronics

Anniversaries

Ann Arbor Human Rights Commission

Ann Arbor Daily Times

Ann Arbor Chamber of Commerce

Has Photo

Old News

Ann Arbor News

William Walter Wedemeyer

George E. Wedemeyer

Jack Stubbs

2280 S Industrial