At Retirement, 2 Veteran Detectives Leave Legacy Of Quality Police Work

At retirement 2 veteran detectives leave legacy of quality police work

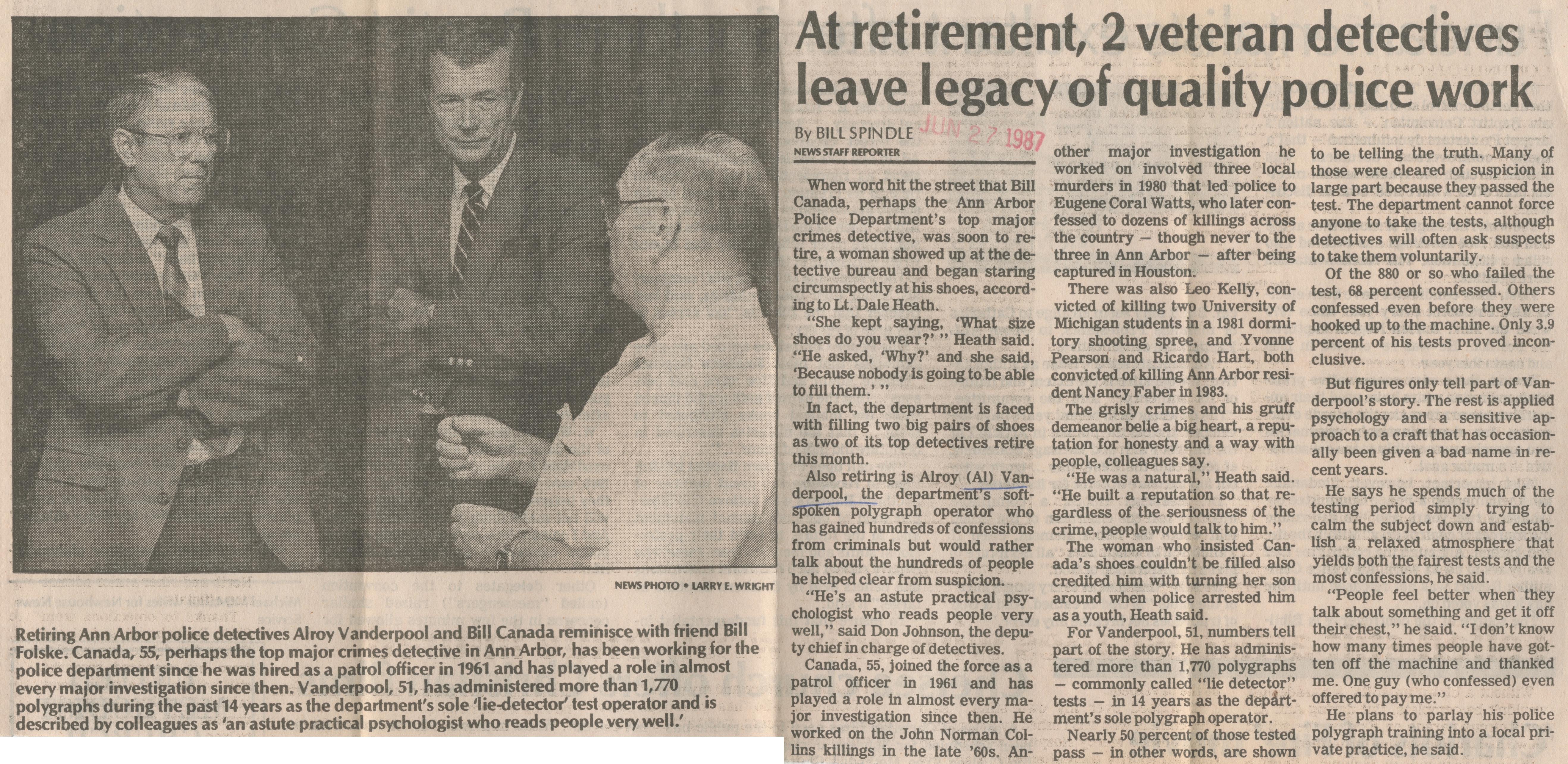

Retiring Ann Arbor police detectives Alroy Vanderpool and Bill Canada reminisce with friend Bill Folske. Canada, 55, perhaps the top major crimes detective in Ann Arbor, has been working for the police department since he was hired as a patrol officer in 1961 and has played a role in almost every major investigation since then. Vanderpool, 51, has administered more than 1,770 polygraphs during the past 14 years as the department's sole 'lie-detector' test operator and is described by colleagues as 'an astute practical psychologist who reads people very well'.

By BILL SPINDLE

NEWS STAFF REPORTER

When word hit the street that Bill Canada, perhaps the Ann Arbor Police Department’s top major crimes detective, was soon to retire, a woman showed up at the detective bureau and began staring circumspectly at his shoes, according to Lt. Dale Heath.

“She kept saying, ‘What size shoes do you wear?’ ” Heath said. “He asked, ‘Why?’ and she said, ‘Because nobody is going to be able to fill them.’ ”

In fact, the department is faced with filling two big pairs of shoes as two of its top detectives retire this month.

Also retiring is Alroy (Al) Vanderpool, the department's soft-spoken polygraph operator who has gained hundreds of confessions from criminals but would rather talk about the hundreds of people he helped clear from suspicion.

“He’s an astute practical psychologist who reads people very well,” said Don Johnson, the deputy chief in charge of detectives.

Canada, 55, joined the force as a patrol officer in 1961 and has played a role in almost every major investigation since then. He worked on the John Norman Collins killings in the late ’60s. Another major investigation he worked on involved three local murders in 1980 that led police to Eugene Coral Watts, who later confessed to dozens of killings across the country - though never to the three in Ann Arbor — after being captured in Houston.

There was also Leo Kelly, convicted of killing two University of Michigan students in a 1981 dormitory shooting spree, and Yvonne Pearson and Ricardo Hart, both convicted of killing Ann Arbor resident Nancy Faber in 1983.

The grisly crimes and his gruff demeanor belie a big heart, a reputation for honesty and a way with people, colleagues say.

“He was a natural,” Heath said. “He built a reputation so that regardless of the seriousness of the crime, people would talk to him.”

The woman who insisted Canada’s shoes couldn’t be filled also credited him with turning her son around when police arrested him as a youth, Heath said.

For Vanderpool, 51, numbers tell part of the story. He has administered more than 1.770 polygraphs - commonly called “lie detector” tests - in 14 years as the department’s sole polygraph operator. Nearly 50 percent of those tested pass - in other words, are shown to be telling the truth. Many of those were cleared of suspicion in large part because they passed the test. The department cannot force anyone to take the tests, although detectives will often ask suspects to take them voluntarily.

Of the 880 or so who failed the test, 68 percent confessed. Others confessed even before they were hooked up to the machine. Only 3.9 percent of his tests proved inconclusive.

But figures only tell part of Vanderpool's story. The rest is applied psychology and a sensitive approach to a craft that has occasionally been given a bad name in recent years.

He says he spends much of the testing period simply trying to calm the subject down and establish a relaxed atmosphere that yields both the fairest tests and the most confessions, he said.

“People feel better when they talk about something and get it off their chest,” he said. “I don’t know how many times people have gotten off the machine and thanked me. One guy (who confessed) even offered to pay me.”

He plans to parlay his police polygraph training into a local private practice, he said.

Article

Subjects

Bill Spindle

Retirement

Lie Detectors

Criminal Investigations

Ann Arbor Police Department

Has Photo

Old News

Ann Arbor News

Yvonne Pearson

William D. Canada

Ricardo Hart

Nancy Faber

Leo Kelly

John Norman Collins

Don Johnson

Dale T. Heath

Coral Eugene Watts

Alroy Vanderpool

Larry E. Wright