Take This Swamp And Shovel It

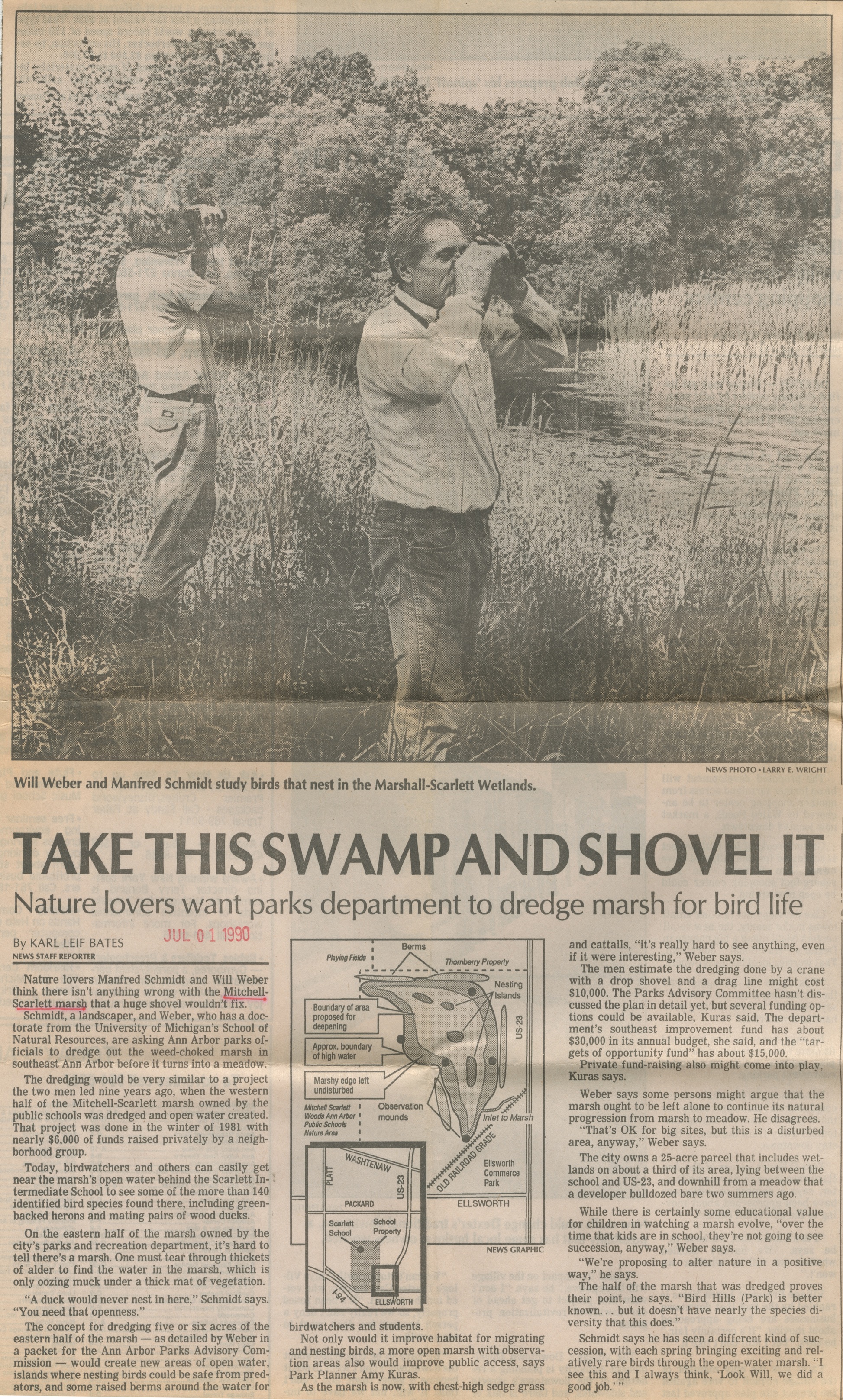

NEWS PHOTO * LARRY E. WRIGHT

Will Weber and Manfred Schmidt study birds that nest in the Mitchell-Scarlett Wetlands

TAKE THIS SWAMP AND SHOVEL IT

Nature lovers want parks department to dredge marsh for bird life

By KARL LEIF BATES

NEWS STAFF REPORTER

Nature lovers Manfred Schmidt and Will Weber think there isn't anything wrong with the Mitchell-Scarlett marsh that a huge shovel wouldn't fix.

Schmidt, a landscaper, and Weber, who has a doctorate from the University of Michigan's School of Natural Resources, are asking Ann Arbor parks officials to dredge out the weed-choked marsh in southeast Ann Arbor before it turns into a meadow.

The dredging would be very similar to a project the two men led nine years ago, when the western half of the Mitchell-Scarlett marsh owned by the public schools was dredged and open water created. That project was done in the winter of 1981 with nearly $6,000 of funds raised privately by a neighborhood group.

Today, birdwatchers and others can easily get near the marsh's open water behind the Scarlett Intermediate School to see some of the more than 140 identified bird species found there, including greenbacked herons and mating pairs of wood ducks.

On the eastern half of the marsh owned by the city's parks and recreation department, it's hard to tell there's a marsh. One must tear through thickets of alder to find the water in the marsh, which is only oozing muck under a thick mat of vegetation.

"A duck would never nest in here," Schmidt says. "You need that openness."

The concept for dredging five or six acres of the eastern half of the marsh--as detailed by Weber in a packet for the Ann Arbor Parks Advisory Commission--would create new areas of open water, islands where nesting birds could be safe from predators, and some raised berms around the water for birdwatchers and students.

Not only would it improve habitat for migrating and nesting birds, a more open marsh with observation areas also would improve public access, says Park Planner Amy Kuras.

As the marsh is now, with chest-high sedge grass and cattails, "it's really hard to see anything, even if it were interesting," Weber says.

The men estimate the dredging done by a crane with a drop shovel and a drag line might cost $10,000. The Parks Advisory Committee hasn't discussed the plan in detail yet, but several funding options could be available, Kuras said. The department's southeast improvement fund has about $30,000 in its annual budget, she said, and the "targets of opportunity fund" has about $15,000.

Private fund-raising also might come into play, Kuras says.

Weber says some persons might argue that the marsh ought to be left alone to continue its natural progression from marsh to meadow. He disagrees.

"That's OK for big sites, but this is a disturbed area, anyway," Weber says.

The city owns a 25-acre parcel that includes wetlands on about a third of its area, lying between the school and US-23, and downhill from a meadow that a developer bulldozed bare two summers ago.

While there is certainly some educational value for children in watching a marsh evolve, "over the time that kids are in school, they're not going to see succession, anyway," Weber says.

"We're proposing to alter nature in a positive way," he says.

The half of the marsh that was dredged proves their point, he says. "Bird Hills (Park) is better known...but it doesn't have nearly the species diversity that this does."

Schmidt says he has seen a different kind of succession, with each spring bringing exciting and relatively rare birds through the open-water marsh. "I see this and I always think, 'Look Will, we did a good job.'"

Article

Subjects

Wetlands

University of Michigan - Faculty & Staff

Scarlett-Mitchell Nature Area

Parks - Ann Arbor

Mitchell-Scarlett Woods

Conservation

Bird & Birding

Ann Arbor Public Schools

Ann Arbor Parks Advisory Commission

Has Photo

Old News

Ann Arbor News

Will Weber

Manfred Schmidt

Amy Kuras

Larry E. Wright