Let's Put On A Play! A History of the Ann Arbor Civic Theatre

On February 23, 1935 the Ann Arbor Daily News announced the formation of a “Civic Amateur Theatre Group intended to meet the need for a dramatic organization in Ann Arbor.” It was open to anyone, not just those interested in appearing in plays but also those who were willing to work behind the scenes.

The group had begun in 1929 as a private club that met in homes and school rooms. When they invited the general public to join, they already had 250 members and had chosen a play to be put on in a month, The Late Christopher Bean by Sidney Howard. Their second production, in May of 1935, featured dance and music as well as two one-act plays to “offer a representative resume of the many talents and interests of the members.” The News reported that the group “follows the idea of English community drama” and that they were obviously filling “a real need in Ann Arbor.”

In the fall they started a new season with meetings every other week at the Michigan Union, alternating between laboratory productions and play reading. After the meetings they had a social time with “cigarettes and coffee.” One of the lab productions was a one-act play written by a local man, Dr. Harold Whitehall, the assistant editor of the Middle English Dictionary.

Their public performances were usually comedies or mysteries. Anyone familiar with pre- World War II movies will recognize many of the titles such as You Can’t Take It With You, Easy Living and Arsenic and Old Lace. They used the Michigan Union Small Ballroom for their lab productions, but moved into bigger venues for their public shows, starting with school auditoriums and later into Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre.

Their shows got wide coverage in the News and were enthusiastically reviewed. Women participants were identified by a “Mrs.” in front of their husband’s name and addresses were always given. Where one lived was evidently an important identifier in those days. Although reports always sound like the group was doing great, a later article stated that they were beset with money worries during this time. Not surprising, since Ann Arbor, like the rest of the country, was in the midst of the great depression.

In 1942 they reincorporated as the “Ann Arbor Civic Theatre, removing “amateur” from the title. They continued operating during the first two years of World War II and put on several fundraisers to help finance the Chamber of Commerce’s War Services Office. They disbanded from 1944-46 when they found it hard to keep going with a shortage of manpower.

When the Civic Theatre reconvened in 1947, they could no longer use the Michigan Union as their headquarters. Soaring enrollments, with veterans returning to school on the GI bill, meant the Union was needed for university functions. The Civic Theatre rented space at 305 ½ Main for rehearsals and scenery building until the city let them use the old log cabin at Burns Park. When the log cabin was torn down to make room for a park shelter, they moved to an abandoned one-room school at Wagner and Ellsworth. They continued to use area theaters for their public productions. My Sister Eileen was their first post war show, followed by The Late George Apley, a benefit for the police department to buy a new cruiser.

In 1951 they hosted their first awards banquet. Ted Heusel, who had joined the year before, received two “Oscars” for performing and directing Strange Bedfellows, a play that the reviewer said was “as easy to take as an innerspring mattress.” Heusel stayed involved for many years, sometimes directing all the plays in a season. When, because of failing health, he stepped down in 1994, he estimated that he had acted or directed in over 200 shows. His wife, Nancy Heusel, often played leading ladies, both under his direction and those of others.

In the post-war years the Civic Theatre widened their offerings. War-themed plays were a staple such as Mr. Roberts, Stalag 17, and Diary of Anne Frank. Works of major playwrights were presented - Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, Clifford Odets, George Bernard Shaw. It was productions of Miller’s All My Sons and Shaw’s Major Barbara that so impressed Burnette Staebler, that she became active in the Civic Theatre, both as an actor and a director. In a later interview she said, “I decided this was a group that was interested not just in being a little social club that gives plays for fun, but were really interested in doing the very best job that amateurs can do.”

Reviewers were also taking them more seriously, sometimes actually critical of productions, something that they had not done in the “amateur” days. In 1957 when the group first tried to do Shakespeare, the reviewer wrote “Merchant of Venice too much for Civic Theatre.” Undeterred, the next year they put on Julius Caesar, offering special matinees for junior and senior high school students.

The introduction of musicals was better received. The reviewer wrote in 1958 that the production of Guys and Dolls was better than expected, saying it “draws skeptical critic’s raves.” From then on musicals were a staple and always an audience pleaser. In 1958 Heusel directed Mia Mine, a play by his friend Harriet Bennett Hamme, daughter of the notorious Harry Bennett, henchman of Henry Ford. Although Hamme admitted that the play takes place in a mansion similar to the one she grew up in, she said none of the characters were based on living people. As a student at the University of Michigan, she had earned a Hopwood Award for the play.

Real life events intervened at the October, 7, 1960 production of Darkness at Noon when the curtain at Mendelssohn was delayed until 8:45 to allow the audience time to watch the Kennedy - Nixon debate, which was to end at 8:30. They also had two televisions in the lobby.

The group was able to expand its work space in 1961 when the city gave them temporary space in the unused utility building at 803 W. Washington, at the end of Mulholland. They bought the building the next year. With financial contributions, plus lots of volunteer hours and donated materials, they built a meeting room, studio for classes, rehearsal space, storage for sets and props, and a costume room and theater space that seated 66 people.

In 1967 they began their “Summer Workshop Programs” which they described as “plays having an experimental flavor that otherwise wouldn’t be produced by the group.” The first offering was two plays by Ionesco. This model of presenting more daring plays in their own space continued in other locations, albeit with different names. The more mainstream plays were always put on in area theaters.

Beyond their own volunteer base, they had lots of support in the community when specific needs arose. When they needed coconuts for The Night of the Iguana they put a request in the News that people visiting Florida bring some back. Florida visitors as well as Delta Airlines responded to the plea. When they needed a goat for The Rose Tattoo, they borrowed Henry from a nearby farm, who is shown in pictures looking totally bewildered. In 1976 they had the use of a real Walker and Company carriage for Oklahoma! The carriages were made in the building now home to the Ann Arbor Art Association. The costume room was full of contributions from people’s attics.

In 1969 U-M student Gilda Radner, later of Saturday Night Live fame, played the lead in She Stoops to Conquer. The play received rave reviews with her performance rated the best. “However, the one who is so suited to her role it seems she almost was made for it, or vice versa, is Gilda Radner,” wrote long time News drama critic Norman Gibson.

In 1979, having outgrown the W. Washington space, they put a down payment on the Elks building at 338 S. Main. It had ample room for all their behind the scenes activities: set making, costume room, box office, meetings, rehearsals, and storage. It also had room to create a performance area they dubbed the “Main Street Stage” to replace the “Summer Workshop Programs.” Their old building was converted to apartments and later into condos.

In 1984, in honor of their upcoming 50th anniversary, they revived their first play, The Late Christopher Bean. Although outdated, it got rave reviews from the News’ Christopher Potter who said without the talented cast it could have been a disaster, but instead was a wonderful resurrection of “a wispy little comedy from a dusty corner its languished in for half a century.”

Another revival occurred in 1986 when Ted Heusel repeated himself by Gypsy using much of the same cast that he used in 1964 including Judy Dow as Mama Rose. In an interview with The News, he laughed about how times had changed. In the 1964 production, there were police in the audience, responding to the complaint that there was stripping in the show. “There were just bumps and grinds, but it’s nothing today.” explained Heusel.

In 1987, after ten years of ownership, they sold the building. Money was tight and they had a good offer for its sale, so they moved into the American Legion Hall at 1035 S. Main. Because they were still on Main Street they kept the name “Main Street Stage,” for their more adventuresome productions.

In 1991 they bought a former roller skating rink at 2275 Platt, after what they called “seven decades of wandering in an architectural wilderness, no more temporary offices and converted meeting halls.” A clever repurposing by architect John Mouat created a versatile theater with seating for 175 in the area where there had been skating, plus three rehearsal rooms and a spacious lobby and snack bar.

They kept the same format, albeit with a name change. The more experimental plays were presented on site and were called “the Second Stage”, a name they changed three years later to “Footlight Productions” to clear up any misunderstandings that they were lesser offering. At the same time they changed “MainStage,” the name for their bigger productions in downtown theaters to “CenterStage.”

In 2000 they sold their building to Vineyard Christian fellowship, a church out of Milan. They had not raised as much money as they had hoped and were unable to make the big balloon payments coming up. They had a large volunteer base but never seemed to be able to raise enough money for brick and mortar establishments. They temporarily moved into the old Performance Network space at 408 W. Washington, which was empty because the building was soon to be torn down for the building of the new Ann Arbor Y. They called that venue “Ann Arbor Civic Downtown.”

In 2004 they moved to 322 West Ann, into rented quarters. “We would not want to own outright again ….We learned the hard way that’s not what our membership is really interested in,” said program director Cassie Mann in a 2004 interview. The Oldnews Collection, which ends in 2009, records the many plays they put on in that time, using their time tested system of smaller offering in their home base and bigger ones in area theaters.

A2CT Programs

Take a look at the Ann Arbor Civic Theatre programs to follow over 80 years of amazing shows. Relive the shows you saw or discover new ones with cast lists, notes from A2CT presidents and directors, and hundreds of advertisements from local businesses who sponsored A2CT shows over the years.

Ann Arbor News Articles

AADL has digitized hundreds of articles from the Ann Arbor News documenting the history of the Ann Arbor Civic Theatre as it happened, starting with the announcement of the first play and following through years of great performances. Read the previews and reviews of plays gone by and learn about the ups and downs of putting on over 80 years of shows.

Photos

Let your memory of past shows be rekindled (or see glimpses of what you missed) with this collection of photographs of the Ann Arbor Civic Theatre. Photos include those taken by A2CT and many by Ann Arbor News photographers of performances, rehearsals, behind the scenes work, and even theatre buildings.

Open To The Public: A History of the Ann Arbor District Library

At the dedication in 1991 of the second addition to the downtown library, director Ramon Hernandez explained that his goal was to have the library be strong in three areas: children’s services, reference, and popular materials. This collection of Ann Arbor News articles shows that these were goals from the very beginning.

The first article, dated 1886, is an editorial written when the library was still part of the high school, then at the corner of State and Huron (site of today’s North Quad), and the first librarian, Nellie S. Loving, was just three years into her almost 40 year tenure. The headline reads “GOOD READING FREE: The Public Library of this City and the Good it is Doing.” Although there had been earlier lending libraries in Ann Arbor, this was the first free one. Starting in 1883, on Wednesdays from 4 to 5 p.m. the high school’s collection of 2,500 books was available to check out by anyone in the school district over fourteen years of age. The library remained connected with the public school system until 1995. When the high school library opened to the public, the main subscription library in town was the Ladies Library Association, who deeded their collection of 4,600 books to the public library in 1908.

After the 1886 article, the collection jumps to 1930 when the first article is fittingly about children reading, always a key mission. That summer young people could join the “Around the World Club” and after reading ten books about different countries and writing reports on them, were congratulated on having completed the “Library Cruise.” A picture shows the participants in front of the library, the façade of which is now preserved on the Huron Street side of North Hall. Summer reading programs continued for many years using themes such as Paul Bunyan, Space Ships, and Knights. Activities the rest of the year included story hours, talks on children’s books, children’s book week, reading clubs, and displays of children’s books. When the bookmobile was introduced in 1954, it was touted as a way that children could more easily get books. In the summer it stopped at all the supervised playgrounds.

From the beginning, the library worked to be relevant to current conditions. The second article in the 1930s section, dated 1933 in the midst of the Great Depression, is headlined “Unemployed Make Wide Use of Public Library.” Otto Haisley, superintendent of schools, boasted what a community resource the library continued to be, giving the unemployed a chance to make good use of their unsought time for leisure.

From the beginning, the library worked to be relevant to current conditions. The second article in the 1930s section, dated 1933 in the midst of the Great Depression, is headlined “Unemployed Make Wide Use of Public Library.” Otto Haisley, superintendent of schools, boasted what a community resource the library continued to be, giving the unemployed a chance to make good use of their unsought time for leisure.

After World War II, technology began creeping in. In 1947 the Lions Club raised money to buy devices that allowed bedridden people to read on the ceiling, available to check out of the library as long as a letter from a doctor was produced. In 1952 microfilm readers were introduced to save space. The collection started with seventeen magazines, which the New York Times and Ann Arbor News was soon to be added. Library director Homer Chance offered to show anyone how to use the readers. The next year a drop off box, looking very much like a mail box, was underwritten by the Kiwanis and the Friends of the Library. It could take books, but not phonographs, which by then had been added to their list of library offerings. A picture of Homer Chance demonstrating its use appeared in the paper as he stopped his car on a less than now trafficked Huron Street.

Ann Arbor High School moved to West Stadium when the buildings that housed the library and the high school were sold to the University of Michigan and renamed the Frieze Building. After much discussion, the public library decided to stay downtown. They hired Midland architect Alden Dow to design a building on a site they had purchased at the corner of Fifth Avenue and William Street. Dow demonstrated his motto, “gardens never begin and buildings never end” by placing a garden on the roof of the veranda that ran across the front of the building, as well as a second one at ground level in the front of the building. A 1961 picture shows forsythia blooming on top of the veranda.

Ground breaking for the new building at 343 South Fifth Avenue took place in October 1956. Its progress was well documented in photos, starting with the basement being dug and ending with staff filling the shelves with books. The final cost was $170,000. Pictures of the interior show an open floor plan with lots of natural light, outfitted with modern furniture of the day. The card catalogue was prominently placed where it could be seen when people entered. There was enough room that students were encouraged to study there. Upstairs a listening room allowed patrons to enjoy music or spoken word records. At the dedication in 1957, Howard Peckham, director of the University of Michigan’s Clements Library, said the new library “added an extra room to each of our houses.” He continued that even with TV, movies, and automobiles “nothing replaces the printed book.”

Once settled into the new building the library began adding services such as delivery of books to seniors in 1968 and a circulating art print collection in 1969. In 1986 a compact disc collection was added to the items that could be checked out, followed with video tapes the next year. In 1969 they inaugurated a Black Studies collection. 1974 they published a list of non-sexist children’s books.

The Friends of the Library, organized to help the new library, began holding book fairs every May. The first one, held in 1954 on the grounds where the new library was to be built, was to raise money to buy a bookmobile. After the library was finished, they held the sales on the long front porch, a perfect place protected by the roof of the veranda. The News helped them with publicity by running pictures each year of the ladies, all described by a Mrs. in front of their husband’s names, sorting boxes and boxes of donated books. At the 1962 sale the women dressed in nineteenth-century garb to emphasize that the proceeds were to be used to publish Lela Duff’s Ann Arbor Yesterdays, based on a series of newspaper articles on historic subjects that she wrote.

In 1965 the first branch library opened, named after first librarian Nellie S. Loving. Located on the east side of town at 3042 Creek Drive, just off Packard, it served residents of the neighborhood that had until 1957 been the separate village of East Ann Arbor. Local architect David Osler designed a modern building with floor to ceiling windows and sky lights. Coupled with modern furniture it was very welcoming. In 1966 Osler received an award for the building from the Michigan Society of Architects.

In 1974 the downtown library celebrated the completion of a 20,000 square foot addition that extended straight east behind the original building. Designed by Donald Van Curler, its purpose was to create more seating and shelving space. Wells of windows that created sunny places for patrons to sit and an enclosed garden on the south side fit well with Dow’s original conception.

The second branch library was completed in 1977, this one on the west side of town in the Maple Village Shopping center. A few years later, in 1983, it moved across Jackson Road to the Westgate Shopping Center. A third branch opened in 1981 in the Plymouth Mall Shopping Center and was expanded 1985.

A second addition was opened in 1991 at the Downtown library. Osler Milling added two floors to the Van Curler addition, renovated the older part, and updated mechanical systems to handle increased use of technology. The first computer room was established with three PCs available for patrons to use.

The library was named “Library of the Year” of 1997 by the Library Journal, a national publication. They were becoming more computerized and making plans for new branches when, in 2000, an independent audit showed not only a deficit that the board had not known about, but also that money being embezzled by the finance director. He was arrested and found guilty, but it still left the library with the problem of funding. The board cut expenses, tabled plans for new branches, and raised the millage.

The next year, then-director Mary Anne Hodel left for a new job and the head children’s librarian, Josie Parker, was named interim director. In 2002 she was asked to stay on as permanent director. She started the job with the debt paid off and staff support evinced by the fact that about a dozen attended the board meeting, clapping when she was formally hired.

In 2004 the Malletts Creek Branch opened to replace the Nellie Loving library, which after almost fifty years of use was too small and out of date. Designed by Carl Luckenbach, Mallets Creek was done with attention to latest green strategies and with new technologies including the first self-checkout machines. In 2006 Pittsfield opened to better serve people in the south side of the district library area. Again designed by Luckenbach, it too paid attention to energy efficiently. Parker suggested it could be used for community space and that children could come and run around, a complete turnaround from traditional library philosophy. Traverwood, replacing the Northeast branch, opened in 2008. Architects Van Tine/Guthrie of Northville took the green strategy a step further by using local trees that had been devastated by the Emerald ash borer.

The archive ends in 2009 after Parker negotiated a deal with the Ann Arbor News to obtain their archives after they had stopped publishing a daily print edition.

Ann Arbor's Sister City Program ~ Friendship, Education and Controversy

Since 1965 Ann Arbor has established six sister city relationships, two of which are still very active.

A City Made Beautiful By Gardens - The History of the Ann Arbor Garden Club

The Old News collection of Ann Arbor News articles and photos on the Ann Arbor Garden Club spans more than 80 years, starting in 1930, and chronicles not only changes in the club itself, but in women’s role in the world. When the club started in 1930, it was an era when women were known by their husband’s name with a Mrs. in front of it and took their position in society based on his profession.

The club was formed by a merger of three community groups - The Garden Sections of the Faculty Women’s Clubs, the Woman’s Club of Ann Arbor, and the Ann Arbor Garden Club. Of these three entities, the faculty women’s club appears to be the most active. They had started a yearly garden show in 1926, held in the Hudson-Essex agency on East Washington, and in the years following, at the Detroit Edison building (where the Detroit Edison parking lot is now). Their most memorable activity, a year before the merger, was a visit to Mrs. Henry Ford’s garden arranged by Mrs. Ford’s sister, a Mrs. Grant, the president of the Dearborn garden club.

The new garden club’s mission was “to make Ann Arbor beautiful by improving individual gardens.” Most of the meetings were held in the afternoon, possible in the days when women generally didn’t work out of the home. Their events - elections of officers, meetings in homes, speakers, public service projects - were given full coverage in the Ann Arbor News, often accompanied with pictures of women posing in their gardens dressed in formal attire. The Ann Arbor Garden Club was the first federated garden club in Michigan and took a leadership role in the state as other communities organized.

In the early days the emphasis was on educating themselves and the community on the basics of gardening. Meetings were full of practical information such as the use of herbs or how to grow vegetables. Special interest groups led meetings with talks on their specialties such roses or perennial shrubs. Eli Gallup, the city’s first superintendent of parks, spoke to the group on trees and soil. Larger events open to the public included “A Pilgrimage to God’s First Temples,” a noted expert speaking in 1935 on his “round the world trip to see the rarest and most beautiful trees, illustrated with tinted stereopticon pictures which his wife had colored using notes from the trip.” A 1940s program featured a plant geneticist showing stereopticon pictures “in natural colors of flower fields in Michigan and California.” A talk from the associate editor of Better Homes and Gardens was co-sponsored by U-M’s school of landscape design.

In the summer the club organized garden walks, open only to members, where they visited a selection of each other’s gardens. The garden shows, however, were open to the public as part of the club’s effort to improve gardens city wide. Called the “Ann Arbor Citizen’s Flower Show,” the only requirement was that the flowers be grown in Ann Arbor. During the months leading up to the show, the News articles were full of requests for people to participate, even with clip out entry forms and ads in the paper during the event urging people to attend.

To beautify public areas of the city, the club at various times provided flowers for the Michigan League, the public library, and the post office. In 1937 they sponsored a City Beautiful contest, giving awards for gardens in a wide array of categories such as homes, industry, businesses, fraternities and sororities, and institutions. They also visited schools to teach children about gardening and nature and helped them build bird houses.

In 1938 the Ann Arbor Garden club hosted the state convention of the Federated Garden Clubs. In addition to many displays - how to do ikebana, drawings and photos of plants - the event included visits to prominent member’s gardens. Mrs. James Inglis, considered the club’s founding mother, invited attendees to breakfast. (Her house on Highland has been owned by U-M since 1951.) Mrs. Harry Earhart invited people to tea at her house (now part of Concordia) to see her gardens complete with one of the rare green houses in town. The event ended with a ball at the Michigan Union with gardenias given as favors. The Ann Arbor News photo shows Mrs. Alexander Ruthven, wife of U-M president, presenting a flower to Mrs. Frederick Coller, whose husband was head of U-M’s Department of Surgery.

Hospital work varied but was always one of their major projects. In the 1941, after hearing a talk on flower arranging, they decided to start every meeting with a member demonstrating a different arrangement, after which the sample was given to the hospital. In 1942 they committed themselves to keeping the ninth floor of University Hospital filled with flowers. They first collected vases that their members were not using. They then arranged that every Wednesday members could bring flowers to the ambulance entrance and hand their contributions to an attendant, thus avoiding the need to park.

The first mention of World War II in the garden club articles occurred in January 1942, a month after Pearl Harbor, when members putting together the club book announced that it “was designed to meet war conditions.” They assured the group that they had taken into account a shortage of materials and increased costs and added information on Victory Gardens. The club finished out the year with a speaker on vegetables and a garden walk, after which there is no mention of the garden club for the next seven years. These same ladies were no doubt using their organizational skills to do war work. See “Ann Arbor Goes to War” in Old News.

Articles about the Garden Club reappeared in 1949 with the announcement of an exhibit at Clements Library that included books and drawings about flowers and gardening. In the post-war era the club returned to many of their original projects but with less of an emphasis on basic gardening techniques and more interest in the wider world. Their new beautification project was raising money for a Shakespeare Garden at the Michigan League. The garden was to contain plants mentioned in the Bard’s works. An art walk through selected gardens was organized, with sculpture loaned by the Forsythe Gallery. Programs often focused on other nations, such as a talk by a member who had returned from Japan on the gardens of that country or a Christmas program on Christmas tree decorations of others lands.

Club members were interested in, and became experts in, a new field called “garden therapy.” They worked with patients at the County Hospital (where the Meri Lou Murray Recreation Center now stands) teaching them how to make corsages and do flower arrangements. They visited children in University Hospital, showing them how to work with fresh flowers. They also continued working with children through the schools, planting bulbs at Eberwhite, working with Wines’ students to set up a flower show, helping Thurston students plant fir trees to later replant nearer the school building, and awarding a conservation scholarship to a teacher for summer camp at Higgins Lake.

The intense coverage the News gave the garden club in the pre-war years lessened as the town grew and more activities vied for attention. In the 1980s women gradually began being referred to by their Christian names, sometimes used interchangeably with Mrs. in the same article.

In 1991 the garden club took on the big job of reinstating the yearly garden shows, which they had stopped in World War II. After the war they held events that they called garden shows but they were small events reserved mainly for their members. The new one was, and is, for the whole community, as were the original ones. In 2001 garden club president, Kathy Fojtik encouraged “a large contingent of people to bring their plants, something they’ve spent time raising.”

In the twenty-first century the News gave the garden club much less coverage, with only an occasional article, usually about events open to the public such as an upcoming garden show or garden tour. The last one in the collection is a 2006 article noting that the garden club gave Matthaei Botanical Gardens a decorative garden gate.

Hill Auditorium’s Hundredth Birthday

Hill Auditorium, built in 1913, turned a hundred in 2013. To celebrate this milestone, the Ann Arbor District Library has scanned articles about the auditorium from the Ann Arbor News archives. Seen in the long perspective the changing programs mirror the interests and concerns of the community.

Hill Auditorium was built using $200,000 that Arthur Hill, U-M regent, alumnus, and Saginaw lumber baron, had left in his will for that purpose. It was the first university building on the north side of North University, replacing U-M professor Alexander Winchell’s 1858 octagon house. The auditorium was designed by Albert Kahn, best known for his Detroit factories but soon to become U-M’s most prolific architect with major buildings such as Angell Hall, Burton Tower, Hatcher Library, and the Clements Library to his credit.

It is generally agreed that Kahn was inspired by Louis Sullivan’s Auditorium Building in Chicago for the exterior design of Hill. For the interior, he was guided by acoustic expert Hugh Tallant, who was brought in from New York. Although it was men such as Albert Stanley, Henry Frieze, and Francis Kelsey, founders of University Musical Society and the School Music, who had been lobbying for a better performance venue, U-M president Marion Burton told Tallant his assignment was to create a space where the whole student body could meet and be able to hear the speaker. Tallant’s final product did what they asked, but also created a wonderful space for music, attested to by the world famous performers who come back again and again. (See UMS site.)

The dedication of Hill Auditorium, June 25, 1913, was headline news in that day’s paper. An hour-long parade led by a fife and drum corps, followed by a who’s who of important people and the whole senior class, wound its way from central campus to Hill. A vocal music program including the Messiah’s Hallelujah chorus opened the program, thus marking the first time the public heard music in the auditorium.

Four men made addresses, two representing the university and two from the state level but none from the music community. U-M emeritus President James B. Angell, who had been a personal friend of Arthur Hill, at the request of the Hill family, presented the building to the university and the state. U-M regent William Clements (himself to later be donor of the library that bears his name) accepted it for the university, while Governor Woodbridge Ferris and Senator Charles E. Townsend accepted it for the state. The latter is of interest in that from the beginning the auditorium was for all, not just the university community, which has indeed been the case.

Now best known for music, when the archive starts in Oct. of 1924, the events for the rest of the year included two music series and five talking programs. The latter consisted of the Choral Union and another series with the Sousa Band headlining. The spoken programs included two religious services, Vilhjalmur Steffansson on his Arctic adventures, a pro-League of Nations speaker, and a debate between U-M and the Oxford Union on prohibition. At the end of the evening, the packed auditorium voted for the U-M team who were on the pro side.

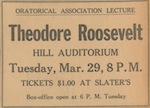

Spoken word events continued to lead for the rest of the 1920s although music was well represented especially with the May Festival, a three- and later four-day celebration of music which had begun in 1894 and continued until 1995. Notable speakers included Will Rogers and Theodore Roosevelt, the latter talking about his hunting trip in Central Asia. Interest in faraway places continued with a program on Mongolia and a visit from the Japanese ambassador encouraging friendship between the two countries. The auditorium was also used for local events such as a debate between Ann Arbor High School and Albion High School over government ownership of coal mines.

The 1930s continued with the same mix. May Festivals were supplemented the rest of the year by famous performers such as Paul Robeson, Ted Shawn, Sergei Rachmaninoff (listed as “Russian pianist”), Vladimir Horowitz, and the “boy violinist” Yehudi Menuhin. World events could be followed with an equally impressive roaster of speakers including Winston Churchill in 1932 warming that the world was facing disaster and Countess Alexandra Tolstoy, daughter of the novelist, explaining the problems in her former homeland. Other educational lectures included ones on Christian Science, historic Washington with “colored slides,” and a movie of the 1932 Olympics.  Live theater ran the spectrum from a Broadway production of Robin Hood to a passion play for the religious minded. When famous cellist Gregor Piatigorsky played at Hill in 1937 his girlfriend, Jacqueline de Rothchild, accompanied him so that they could secretly marry away from her family in Europe. Alva Sink, wife of Charles Sink, head of University Musical Society, heard of their plans and insisted that the ceremony be in the Sink home.

Live theater ran the spectrum from a Broadway production of Robin Hood to a passion play for the religious minded. When famous cellist Gregor Piatigorsky played at Hill in 1937 his girlfriend, Jacqueline de Rothchild, accompanied him so that they could secretly marry away from her family in Europe. Alva Sink, wife of Charles Sink, head of University Musical Society, heard of their plans and insisted that the ceremony be in the Sink home.

By the end of the 1930s and into the first half of the 1940s, Hill was used mainly for war-related speakers, starting in 1939 with Eleanor Roosevelt, followed by foreign correspondents Leland Stowe and Anne O’Hare McCormick, Sinclair Lewis debating Lewis Browne on whether fascism could happen here, and Sen. Burton K. Wheeler sponsored by the campus anti-war group.

In 1948, with the war was over and people returning to civilian life, Charles A. Sink suggested that a bigger auditorium should be built to accommodate the increased university enrollment and more demand for concert tickets. Lack of funding, rather than appreciation for the building in the pre-historic preservation days, prevented the project. A year later a major updating of Hil, which an Ann Arbor News editorial described as “creeping over a third of a century,” was announced. The skylights were covered to allow better use of the auditorium during the daytime, the chandeliers taken down because they were considered too old fashioned, and a color scheme of maize and blue used throughout including painting the organ pipes those colors. In the next fifty years only minor changes were made. In 1964 a kiosk announcing coming programs was put around the stately elm in front, which stayed until 1977 when the elm was cut down. In 1973 Hill’s granddaughter donated a portrait of her grandfather. Repairs to the organ were regularly reported.

Interest in world affairs increased after World War II. In the 1950s and 1960s lectures on this topic included a visit from the Philippine Ambassador, a debate with two senators over foreign policy, and a talk By Saturday Review editor Norman Cousins who is described as a “world traveler and analyst.“ Travelogues aimed not just at the curious but to the increasingly large group of foreign travelers became a staple. The effect of television on the movie industry could be seen in the upsurge of travelling shows put on by movie stars including Bette Davis, Ilka Chase, Basil Rathbone, and Burgess Meredith.

The red scare that hit the nation after World War II affected Hill. In May of 1950 a talk by Herbert Phillips, an avowed communist, was cancelled by the U-M regents. Students objected and tried to organize a student/faculty forum to discuss the topic, but that too was cancelled because they couldn’t find a faculty member willing to defend the ban. Fourteen years later, in 1964, the same issue arose, this time the controversial person, neo-Nazi George Rockwell, was allowed to speak, albeit with picketers and lots of heckling. In 1972, after an April Fools’ rally when in spite of no smoking rules, the U-M fire marshal reported that “smoking of marijuana did occur”, the rules were tightened with more conditions on rentals.

The most unusual use of Hill may have been in 1950 when “Buff” McCuster, a former skating partner of Sonja Henie, and a cast of 30 put on an ice show, “Icelandia,” using a portable ice rink. Another unusual program took place in 1956 when a hypnotist demonstrated his skill using volunteers from the audience.

The last part of the collection deals with the most recent restoration that updated systems while returning the décor to as close as possible to Albert Kahn’s original conception. Articles trace the project from its first suggestion in 1989, to approval by the regents in 1993 after a feasibility study, to work finally beginning in 2001, the delay due to slowness of getting donations.

We have several other collections to relating to the history of Hill Auditorium and the University Musical Society.

Photos of Hill Auditorium from the Ann Arbor News Archive

AADL has digitized several images of Hill Auditorium taken over several decades, including this wonderful photograph of Vladimir Horowitz by Ann Arbor News photographer, Jack Stubbs, as well as many others by News photographers Eck Stanger and Robert Maitland LaMotte.

More Photographs at UMS: A History of Great Performances

AADL has digitized hundreds of photographs of UMS performances, including candid backstage shots in Hill Auditorium. This collection is part of UMS: A History of Great Performances, an archive of historical programs and photographs created in partnership with the University Musical Society.

UMS Concert Programs Archive

AADL, in partnership with the University Musical Society, has digitized a full run of historical programs covering 100 years of concerts at Hill Auditorium and over 130 years of UMS concert history. The Programs Archive is available for browsing and full-text searching, and is part of UMS: A History of Great Performances.

Ann Arbor Goes to War

Much has been written about World War II, but this collection of articles from the Ann Arbor News archives does something the general histories can’t: it provides a glimpse of how it would have felt to be living in Ann Arbor during the two years leading up to the war. Old News has culled through the The Ann Arbor News to find the articles from September 1939 to December 1941 that deal with local events related to WWII. The articles start on September 3, 1939, the day after Hitler invaded Poland and end December 12, 1941, five days after Pearl Harbor.

We see how everyone pitched in to help war-struck European countries, how they reacted to the draft, how local industry began gearing up to play their part in the Arsenal for Democracy, and how citizens strived to get educated about the situation. Advertisements for stores and movies add to the feel of what life was like then. People who were in Ann Arbor during those years, or who have family that was, will appreciate that Old News has included the names of people involved, so you can look them up with a simple search.

One of the first articles is an announcement that the Ann Arbor News had printed up 5,900 maps of the European War Zone to give to school age children. The maps, which included naval bases, the British blockade, and the topography of the area, aimed to give “an accurate and comprehensive picture of the war scene.”

When Europe suddenly became a war zone, Ann Arborites’ first concerns were for the safety of friends and relatives who were abroad. In the fall of 1939 the paper was full of stories of narrow escapes that sound like plots for movies. A student traveling home on a Norwegian freighter after bicycling around Europe survived three days on a lifeboat when his ship was sunk by a mine. Another student was briefly arrested on suspicion of being a Nazi spy while taking pictures in England. A report that a British boat with three U-M co-eds on it was torpedoed caused a lot of worry, but they were eventually reported to have reached Ireland. A local family visiting in England finally got passage on a mysterious boat that had been painted grey and was accompanied by an airplane escort. The News followed these and other stories until they could report that the people involved were safely home. Reacting to the fear that our country might be attacked, the local National Guard began holding maneuvers. On the state level, discussions began on how to make our highways strong enough for tanks.

War relief work, most of it organized by women, started almost immediately and was constant through all this period. Under the direction of the Red Cross, local women’s groups began making heavy winter clothes for people in the Balkans as well as Britain and France. At the end of November, the Soviet Union attacked Finland, and for the next few months most of the relief work was aimed directly at raising money to help the Finns. The Woman’s Club led by organizing an evening of songs and one-act plays followed by cards and sewing (called a thimble party). University musical organizations gave a concert to raise more money. Finnish dancers from Detroit headlined another fundraiser. Ann Arbor also hosted many refugees from war-torn Europe.

Although the U.S. was technically neutral until Pearl Harbor, it was clear from the beginning that public opinion was largely on the Allied side. However, there were a few dissenters. In December 1939 radio commentator H. V. Kaltenborn spoke at Hill advocating isolationism. In April of 1940, after another isolationist spoke at Hill, a Nazi flag, described as “a home-made banner, a painted bed sheet,” appeared on the flag pole by the Natural Science building. A month later the columns of Angell hall were painted with numbers one to four with a three-foot red swastika on the fifth, a reference to the “fifth column,” enemies within a state. Reaction in both cases was for officials to immediately take action to remove them. University officials called the latter action the work of “immature pranksters.”

When Germany invaded Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxemburg in May 1940, attention veered from Finland to those countries. The Red Cross opened a knitting center in a donated office in Nickels Arcade where they distributed yarn, and inspected and packed the returned items. Kline’s Department Store announced that people could drop off “old worn shoes, which still have many days wear in them,” in their shoe department to be sent to Europe. Later a Greek war relief committee was formed, made up of leading members of local Greek community as well as a few other community leaders who leant their names to the cause. Another group of about a hundred met every Tuesday to knit and sew for French children under the age of four.

In the summer of 1940 France fell, leading President Roosevelt to sign a peacetime conscription bill on September 16. The next day an article in the News explained that our county had been assigned to provide 250 or 260 conscripts, half from Ann Arbor and half from rest of county. On Oct. 16, all the men in Washtenaw County between the ages of 21-35 were told to show up at their election precinct to register for the draft. Volunteers were recruited to help with the paper work. On that date there were long lines of men waiting, but as the News reported they were “mostly good-natured.” In the following months names of the 14,586 registrants were drawn on a regular basis and those called were taken by bus or train into Detroit to be inducted into the army. In July a second registration was held for men who had turned 21 since October. In July 1941 the first draft objector mentioned was sent to a camp to perform work connected with the war.

Along with the draftees, there was a steady stream of enlistments, for the regular army, army pilots, navy, National Guard, and nurses. In 1940 Dr. Edgar Kahn, U-M brain surgeon, offered his services to the American Hospital in Paris. In January, 1941, Stanley Waltz, general manager of the Michigan Union, was called up for duty. By September 1941 twenty faculty members had asked for leave.

FDR’s agreement at the end of 1940 to supply Great Britain with war materials soon affected Washtenaw county as we geared up to do our part in the Arsenal for Democracy. Our most famous contribution was the Willow Run Bomber Plant, where the B-24 bombers were made. First mentioned in May of 1941 with two articles about its siting, it was a continuing story. In July 1941 King Seeley was awarded a contract to make 60 mm mortar ammunition shells and the next month American Broach was given a contract to make units used in gun construction. Soon there were articles complaining that there was a labor shortage, something that was not a problem in the Depression.

New war industry necessitated more materials. The month of July 1941 was devoted to a community-wide aluminum drive, starting with an organizational meeting at the Michigan Union at which most of the major service clubs were represented. The plan was to have two days of picking up contributions from neighborhoods and in addition to provide drop off sites. Wire contraptions called cribs built to hold donations were put on the courthouse house lawn and also on the Fifth Avenue side of the armory. On the days the pick-ups were scheduled, 25 trucks provided by local merchants were driven by volunteers, while fifty Boy Scouts went door to door. One volunteer reported that he was surprised when at one of the houses that he stopped at the resident gave him the coffee pot right off the stove, only to have it happen a second time. Another interesting contribution was from Randolph Adams, director of the Clements Library, who donated his World War I canteen. At the end of the drive Ann Arbor had collected 7,500 pounds of aluminum, almost four times over the goal they’d been given of 2,000. Ann Arbor also gave generously that summer to the USO Drive, raising money to build USO Centers across the United States.

After the successful aluminum drive, the next big push was to urge citizens to buy Defense Stamps. When the stamps, which were sold for 10 cents each, added up to $18.75, they could be exchanged for a Defense Bond worth $25 at maturity. A huge sign urging people to buy them was erected on courthouse lawn using volunteer labor and materials donated by local merchants. A group of high school girls and college co-eds were organized to pass out the cards that the stamps were affixed to. Store customers could take their change in stamps, while many companies offered to automatically deduct stamp purchases from wages. In Sept. ’41 it was announced that Ann Arbor led the nation in per capita buying of saving stamps at $39.77 per capita.

Relief work continued side by side with the military-based activities. While the projects moved around from country to country depending on which one was in the most trouble, English relief work was a constant. An on-going British war relief knitting group met in members’ homes. At the end of 1940 the Women’s Club planned 40 parties for English war relief to be held in private homes, doing what they did for fun but also for a good cause – suppers or desserts, cards including bridge, musicales. The proceeds from the 1941 Juniors on Parade, a yearly production by the Roy Hoyer Dance Studio to showcase the talents of their students, that year featuring military theme numbers, was used to buy a truck with a mobile kitchen to be sent to England. That May a group of women began making windbreaker jackets for British seaman using scrap leather from the car industry. Individual English children could be adopted by proxy for $30 a year, a project many locals participated in including a class at Angell School.

The local Red Cross was the key to much of this activity. They outgrew the office in Nickel’s’ Arcade, moving to what had been the directors’ office in the old Catherine Street hospital, and expanded from knitting sweaters to other knitted items such as mufflers, and mittens and to sewing clothes and quilts, which could be made right there on sewing machines they had at the headquarters. Surgical dressings were made in the Rackham Building. They commandeered all the help could get, such as people accompanying patients to the hospital. The ever-present Boy Scouts helped with the packing. To encourage more cooperation, garments were displayed at Mack and Co., the city’s biggest department store. July of 1941 they began training people for canteen service, followed a few months later by mechanics courses for women so they could become Red Cross drivers.

To feed the public demand for more information on the situation in Europe in the days when sources of news were more limited, there was a constant stream of public lectures. Early on they were mainly by U-M professors putting events in context vis a vis their specialties or their points of view. U-M President Alexander Ruthven felt called on to make pronouncements now and then. The public library, then on Huron, highlighted their collection of books relating to the subject. The local pundits were supplemented by national speakers, who came more often as the situation worsened. Already in 1939 two famous speakers had come to town, Mrs. Franklin Roosevelt (like all the club ladies she is not identified by her first name) and Leland Stowe, Pulitzer Prize winning foreign correspondent, warning about the situation in Europe. A few isolationists and pacifists also spoke, but by and large, at least those reported, were for helping the Allied side. As the war heated up a steady stream of speakers from Europe also came through including Jan Masaryk, son of the deposed president of Czechoslovakia; Count Sforza, leader of the opposition to fascism in Italy; Sir Robert and Lady Mayer asking for help with British children; Mrs. Robert Fraser, former Labor member of London City Council; Jack Jones, a Welsh miner; and Erika Mann, Thomas Mann’s daughter.

Soon after the military draft began, advertisements referencing the situation began showing up, some clearly fitting in with the war effort, while others were more of a stretch of logic. The News suggested that car buyers use their classified ads to buy used cars since new one would soon be hard to find. Kline’s announced they would continue selling silk hosiery so buyers shouldn’t hoard them. A fur company announced it would cancel the debt if man who bought a fur coat for his wife was drafted in the next three months. A Cunningham’s ad suggested that people might want to send a “welcome package,” to friends in the service. Their ad has a picture of a soldiers saying to his friends “Boy oh boy, look what I got from Cunningham’s.” Movies also started having war themes. Early on there were low budget forgettable ones like “Confessions of a Nazi Spy” or “Women in War,” but as the situation worsened Class A movies such as “Foreign Correspondent” and “The Great Dictator” were shown at local theaters. The Military Club held dances at the Armory featuring both local and touring bands and singers.

In mid-September of 1941 a group of ads that at first glance appear to have no connection to the war – undergarments, electric supplies, stoves, pens, windows, appear under the rubric “Retailers for Defense.” Reading on we find an article explaining that a group of local merchants have agreed to a list of wartime policies including keeping prices low, finding replacements for products no longer available, and discouraging speculation.

Dec. 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor, the stage moved to the Far East. News articles talked of soldiers being sent to the Pacific, people worried about friends and relatives caught in Hawaii, and merchants debated whether it was alright to sell Japanese products already on their shelves. Meanwhile, a local shoe store suggested that since there was a war going on that people should give practical Christmas gifts such as shoes.

The Story of Argus Camera

The story of the Argus Cameras, Inc. is one of ideas, perseverance and adaptability.

Founded in the Depression years by businessmen who were as tough as the times, it employed, at its height, 1300 workers and occupied 2 city blocks on 4th Street.

In 1929, local inventor Charles A. Verschoor and Mayor William E. Brown Jr. started a radio manufacturing business with support from local bankers called the International Radio Company. In 1932 they produced the Kadette, the first radio that used tubes instead of a large transformer. Verschoor then traveled to Europe researching the idea of producing a camera (like the Leica) but made and sold for $10. With the first camera rolling off the assembly line in 1936, the name of the company was changed to Argus, after the Greek mythological god of 1,000 eyes. The Model A camera was so popular, it sold 30,000 units by Montgomery Ward in the first week.

In the 1940s, with stiff competition from cheaper Japanese cameras available on the market, Argus diversified its product lines with projectors, optical and specialty equipment for several United States Department of Defense contracts during WWII, and the Korean War, thus saving many local jobs.

Local historians like to point out that Argus Cameras, as one of Ann Arbor’s early industries, was 100% Ann Arbor: 100% Ann Arbor capital, 100% Ann Arbor brains, and 100% Ann Arbor people. The Old News staff have gathered decades of news articles, photos and videos that trace the rise and decline of this very important manufacturer in local history.

While the business no longer exists, Argus cameras remain much sought-after collectibles. (See them at the Argus Museum Exhibits and photos taken by AADL photographer Tom Smith). The original Argus buildings still stand, now used by various departments of the University of Michigan, and inspired local author Steve Amick’s second novel Nothing but a Smile (2009).

AADL has partnered with the Argus Museum to digitize a wide variety of images and documents that build a fuller picture of what it was like to work at Argus Camera, its products, people, and impact.

Ann Arbor News Articles

AADL has digitized hundreds of articles from the Ann Arbor News documenting the history of Argus Camera as it happened. These articles include announcements of new products, changes in the company, and the company's impact on the Ann Arbor Community. Argus Camera's role as an industry leader and a major employer in the area assured that coverage by the Ann Arbor News was in-depth.

Argus Eyes

AADL has digitized the Argus Eyes, the employee newsletter of Argus Camera. This publication includes details about the company and its workers, from descriptions of new product lines and facilities to birth announcements and company picnics. And of course, given its source, it is also full of spectacular photos, many of them from the Ann Arbor area.

Podcasts

AADL has conducted the following interviews regarding the history of Argus Camera: -Cheryl Chedister, Argus Museum Curator -Milt Campbell, Art Dersham, and Elwyn Dersham, long-time Argus Camera employees -Art Parker, long-time Argus Camera employee

Argus Camera Publications

In addition to the Argus Eyes, the Argus Museum and AADL have made available digitized copies of many of the publications created by the Argus Camera organization over the years. These include instruction manuals for many of Argus's products, parts lists for the same, and educational booklets on how to take better photographs using Argus cameras.

Photos

The Argus Museum and AADL have also made available a collection of photographs of Argus products and the museum itself. These include high-resolution photos of some of Argus Camera's most iconic creations, from the Kadette Radio to the Argoflex camera.

Argus Videos

We've also digitized two historic films about Argus cameras, Argus Eyes for Victory, from 1945 and Fine Cameras and How They Are Made, from 1953.

Close Encounters in Washtenaw County

In the early morning hours of March 14, 1966, Washtenaw County sheriff's deputies reported sighting "four strange flying objects" in Lima Township. Soon police agencies from Livingston County, Monroe County and Sylvania, Ohio were also reporting "red-green objects . . . moving at fantastic speeds." By the end of the day the Civil Defense and U.S. Air Force were called in to an investigation that has never really ended for many of those involved.

AADL has assembled all the articles that dominated the Ann Arbor News for weeks in 1966 and continues to resurface through sightings, interviews and research into UFOs and extraterrestrial life. Two facets of the UFO story make it especially compelling. Washtenaw County Sheriff Douglas J. Harvey did not immediately dismiss the sightings. In fact, he demanded a top-level investigation and challenged the U.S. Air Force's conclusions. Equally persistent was Bill Treml, the legendary and intrepid police beat reporter for the Ann Arbor News. His stories dominated the local pages of the paper with in-depth interviews with witnesses, seemingly 24-hour coverage of police operations in tracking the UFO sightings, and a dogged pursuit of U.S. government officials investigating the sightings.

The UFO story provides an interesting look at the way news events affect the lives of the participants and their communities. The Dexter family that reported the UFOs near their farm was overwhelmed by the coverage, became victims of vandalism and eventually distanced themselves from the story. The UFO sightings proliferated and swept Washtenaw area communities into a worldwide news event. Read the articles and decide for yourselves whether Washtenaw County's history includes close encounters of the first, second or third kind.

AADL Talks To Former Washtenaw County Sheriff Doug Harvey about the 1966 UFO Sightings

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| AADL Talks to Doug Harvey about the 1966 UFO Sightings | 4.53 MB |

Michigan Basketball: The Cazzie Years

Colleges across America are once again gripped by March Madness. The University of Michigan Wolverines are in the thick of the NCAA’s annual contest to name the No. 1 men’s college basketball team. The Maize & Blue are seeded fourth in the Midwest.

To celebrate this annual hoopla, the Ann Arbor District Library is offering an opportunity to turn back the clock and experience the triumphs of an earlier Wolverine team, the 1963 ~ 1966 squad coached by Dave Strack and led by All-Americans Cazzie Russell and Bill Buntin.

The ups and downs of the three-time Big Ten champions was chronicled in the Ann Arbor News, especially in the passionate reporting of Wayne DeNeff. These articles are available online through the Old News site, presenting the dramatic story of a great team anchored by two outstanding players. Buntin set an all-time school scoring record, only to see it broken by his teammate Russell the following year.

The 1964 team made it to the Final Four, falling to Duke in the semifinal. The 1965 team had no losses going into its final Big Ten game before losing to bitter rival Ohio State, but they were named the No. 1 team in America by AP and UPI. The team went on to run through the NCAA playoffs with wins against Dayton and Vanderbilt. In the semifinal game they beat Ivy League champion Princeton and that year’s player of the year Bill Bradley. They lost in the final to the UCLA Bruins, another victim of John Wooden’s record-setting 1960s basketball juggernaut. At the time only 23 teams competed in the playoffs and only one team could compete per conference. Russell was named 1966 player of the year. Russell and Buntin had strong support from Oliver Darden, Larry Tregoning, George Pomey and other excellent players.

The News stories provide a glimpse of college basketball in a less frenzied media atmosphere, presented with behind the scenes atmosphere, drama and heart.

To see all the articles and photographs about the Cazzie years, click here.

AADL recently interviewed one of the Wolverine’s big players from the 1964 and 1965 championship runs, George Pomey. George took on some of the toughest guard assignments in NCAA basketball history. His stories of student life, sports in a different era and how the team has remained close over the years is not to be missed.

While researching the Wolverine's 1964 ~ 1966 NCAA Championship runs we came across another bit of Michigan history, the debut of longtime Men's Glee Club director Philip A. Duey's fight song, Go Blue! Read articles on Mr. Duey's amazing song, his career at Michigan and even hear an excerpt of the song.

John Norman Collins and the Coed Murders

The Coed Murders riveted Washtenaw county from the first murder in July 1967 to John Norman Collins' conviction three years later on August 19, 1970. The Ann Arbor News featured hundreds of articles over these three years and the investigation and trial were covered in detail by News police reporter William B. Treml. A detailed summary of the Coed Murders is available in our online version of True Crimes by Sergeant Michael Logghe, formerly of the Ann Arbor Police Department. We've pulled together some highlights below.

You can search and browse using keywords such as Coed Murders, Michigan Murders, John Norman Collins - Murder Trial, or by the people featured in the articles, including John Norman Collins, the victims (listed below), Prosecutor William F. Delhey, Chief Defense Counsel Joseph W. Louisell, Washtenaw County Sheriff Doug Harvey and Judge John W. Conlin.

The Victims Mary Fleszar, Joan Schell, Maralynn Skelton, Dawn Basom, Alice Kalom, Karen Sue Beineman