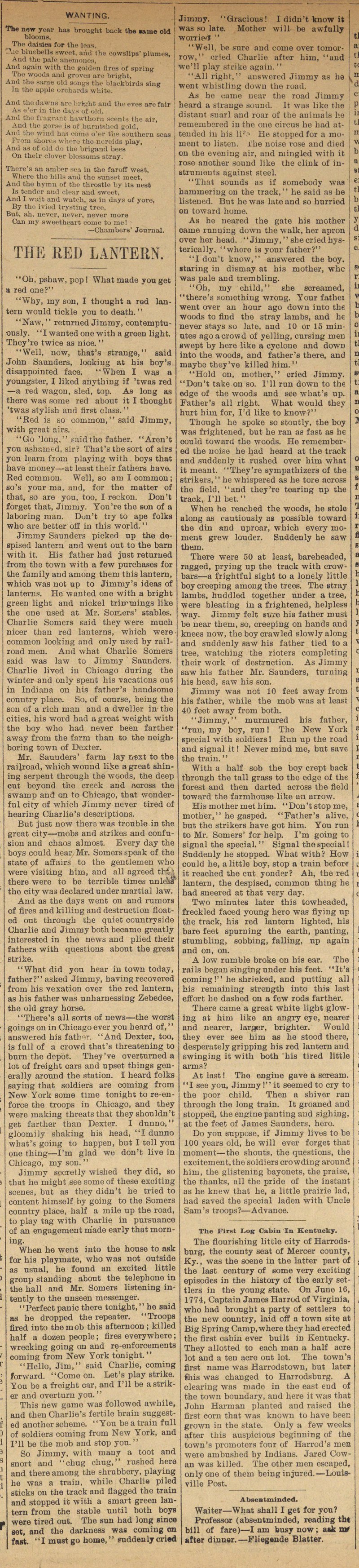

The Red Lantern

"Oh, pshaw, pop ! What made you get a red one?" "Why, my son, I thought a red laniein would tiokle you to death. ' ' "Naw, " refnrued Jimmy, contemptuonsly. "I wantedonewith a green light. They're twice as nice. " "Well, now, that's strange, " said John Saunders, looking at bis boy's disappointed face. "Wbeii I was a youngster, I liked anything if 'twas red - a red wagon, sled, top. As long as ;here was sonie red about it I thought 'twas stylish and íirst class. " "Eed is so conimon," said Jimmy, with great airs. "Go 'long," said the father. "Aren't reu asbaiiH:d, sir? ïhat's thesort of airs ron learn from playing with boys that ïave mouey - at least their fathers bave. Sed comniou. Well, so aru I common ; so's your ma, and, for the matter of ihat, so are you, too, I reokon. Don 't 'orget that, Jimray. You 're the son of a aboring man. Duu't try to ape folks who are better off in this world. " Jimmy Saunders picked up the despised lantern and went out to the barn with it. His father had just returned 'rom the town with a few purohases for he faraily and among them this lantern, which was not up to Jimmy's ideas of anteras. He wanted one with a bright 'reen Hght and nickel trirrtnings like ;he one used at Mr. Soroers' stables. Charlie Soruers said they were much nicer than red lanterns, which werecommon looking and only used by railroad rnen. And what Charlie Somers said was law to Jimmy Saunders. Dharlie lived in Chicago during the winter and only spent his vacations out in Indiana on his father's handsome country place. So, of course, being the son of a rich man and a dweller in the cities, his word had a great weight with ;he boy who had never been fartber away from the farm than to the neighjoring town of Dexter. Mr. Saunders' farm lay &sxt to the raijroad, which wouud liice a great shining serpent through the v6ods, the deep cut beyond the creek and across the swamp and on to Chicago, that wonder - ful city of which Jimmy never tired of hearing Charlie's descriptions. But just now thera was trouble in the great city - mobs and strikes and confusión and chaos al most. Every day the boys could hear Mr. Somers speak of the state pf affairs to the gentlemen wbo were visiting him, and all agreed thi there were to be terrible times unleW' the city was declared under martial law. And as the days went on and rumora of fires and killing and destruction floated out through the quiet countryside Charlie and Jimmy both became greatly interested in the news and plied their fathers with questions about the great strike. "Whatdid you hear in town today, father?" asked Jimmy, having recovered from his vexation over the red lantern, as his father was unharnessing Zebedee, the old gray horse. "There's all sorts of news - the worst goings on in Chicago ever you heard of, ' ' answered his fathor. "And Dexter, too, is full of a crowd that's threatening to burn the depot. They've overturned a lot of freight oars and upset things generally around the station. I heard folks saying that soldiers are coming from New York some time tonight to re-enforce the troops in Chicago, and they were making threatsthat they shouldn't get farther than Dexter. I dunno, " gloomily shaking bis head, "I dunno what's going to happen, but I teil you one thing - I'm glad wo don't live in Chicago, my son. " Jimmy secretly wished they did, so that he migbt seesomeof these exciting scènes, but as they didn't he tried to content himself by going to the Somers country place, half a mile up the road, to play tag with Charlie in pursuance of an engagement made early that morning. When he went into the house to ask for his playmate, who was not outside as usual, he found an exeited little group standing about the telephone in the hall and Mr. Somers listening intently to the unseen mossenger. "Perfect panic there tonight," he said as he dropped the repeater. "Troops flred into thernob this afternoon ; killed half a dozen people ; fires every where ; wrecking going on and re-enforcoments coming from New York tonight." "Helio, Jim," said Charlie, coming forward. "Come on. Let 's play strike. You be a freight car, and I'll be astriker and overturn you. ' ' This new game was followed awhile, and then Charlie's fertile brain suggested anotherscheme. "You be a train full of soldiers coming from New York, and I'll be the mob and stop you. " So Jimmy, with many a toot and snort and "chug chug," rushed here and there among the shrnbbery, playing he was a train, while Charlie piled sticks on the track and flagged the train and stopped it with a smart green lantern from the stable until both boys were tired out. The sun had long since set, and the darkness was coming on fast. "I must go home," suddenly cried Jiininy. "Gracious! I didii't know it was so late, Mother will be awfnlly worrifí " "Well, be sure and cotne over tomorrow, " cried Charlie after hiin, "and we'11 play striko again. " "AU i'ight, " unswered Jiiumy as ha went wbistling down the road. As be name uear the road Jimmy ■ heard a .strange sound. It. was like the I distant snarl and roar of the animáis he i remeiubored in the one circus be had tended iu bis li?." He stoppedfor a I ment to listen, i'be noise rose and died en tbe eveniug air, and ruingled with it ' rose another sound like the clink of i Btrnments against steel. "That sounds as if somebody waa hammering on the track," he said as he listeued. But he was late and so hurried on toward home. As he neared the gate his mother oame running down the walk, her apron over her head. "Jimmy," she cried hysterically, "where is your father?" "I don't know," answered the boy. staring in disruay at his mother, whc ■was pale and trembling. "Oh, my child," she screamed, 'there's something wrong. Your fathei went over an hour ago down into the woods to flnd the stray lambs, and he never stays so late, and 10 or 15 minutes agoacrowd of yelling, cursing men wept by here like a cyclone and dowu nto the woods, and fatber's there, and maybe tbey've killed him." "Hold on, mother," cried Jimmy. 'Don't take on so. I'll run down to the edge of the woods and see what's up, Father's all right. What would they hurt him for, Va like to know?" Tbough he spoke so stotitly, the boy ■was frightened, but he ran as fast as he oould toward the woods. He remembered tbe noise he had heard at the track and suddeuly it rushed over him what t nieant. "They 're sympathizers of tbe strikers, " he whispered as he tore across he field, "and they 're tearing up the track, Pil bet. " When he reacbed tbe woods, he stole along as cautiously as possible toward he din and uproar, which every moment grew louder. Suddenly he saw them. There were 50 at least, bareheaded, ragged, prying up the track with crowDars - a frightful sight to a lonely little üoy creeping among the trees. Tbe Btray lambs, huddled together under a tree, were bleating in a frightened, helpless way. Jimmy feit exise his father must De near them, so, creeping on hands and snees now, the boy crawled slowly along and suddenly saw his father tied to a ;ree, watching tbe rioters coinpleting their work of destruction. As Jimmy saw his father Mr. Saunders, turuing ais head, saw his son. Jimmy was not 10 feet away from ais father, while the mob was at least 40 feet away from both. "Jimmy," murmured his father, "run, my boy, run I The New York special with soldiers I Run up the road and signal it ! Never mind me, but save the train. " With a half sob the boy crept back tbrough the tall grass to tbe edge of the forest and then darted across the field toward the farmhouse like aa arrow. Hismotbermet bim. "Don't stop me, mother, " he gasped. "Father's alive, but the strikers have got him. You run to Mr. Somers' for help. I'm going to signal the special." Signal tho special! Suddenly he stopped. What with? How could be, a little boy, stop a train bef ore it reacbed the ent yondar? Ah, the red lantern, the despised, common tbing he had sneered at that very day. Two minutes later tbis towheaded, freckled faced young hero was flying up the track, his red lantern lighted, his bare feet spurning the earth, panting, stumbling, sobbing, falling, up again and on, on. A low rurable broke on bis ear. The rails began singing under his feet. "It's coming !" be sbrieked, and putting all his remaining strength into tbis last effort he dashed ou a few rods farther. There carne a great white light glowing at him like an angry eye, nearer and nearer, laraer, brighter. Would they ever see him as he stood there, desperately gripping his red lantern and swinging it with both 'his tired little arms? At last ! The engine gave a scream. "I see you, Jimmy !" it seemed to cry to the poor child. Then a shiver ran through the long train. It groaned and etopped, the engine panting aud sighing, at the feet of James Saunders, hero. Do you suppose, if Jimmy lives to be 100 yoars old, he will ever forget that moment - the shouts, the qtiestions, the excitement.tbe soldiers crowding around him, the glistening bayonets, tbe praise, the thanks, all the pride of the instant as he knew that he, a little prairie lad, had saved the special laden with Uncle Sam's

Article

Subjects

Ann Arbor Argus

Old News