Acapulco Gold

GB: Another thing that's different this year that we did not have last year is that one of the county organizations in Salano County has organized a monthly state-wide initiative newspaper called the Grassroots Gazette. The Gazette has been coming out every four to six weeks about sixteen pages long, about the initiative and marijuana news coming from other states. The Gazette is being sold on the streets and each person who wants to sell the Gazette gets to keep a dime for every copy he/she sells. So we are using this paper as a vehicle to get information on the initiative out to the people as well as helping support people working for the initiative.

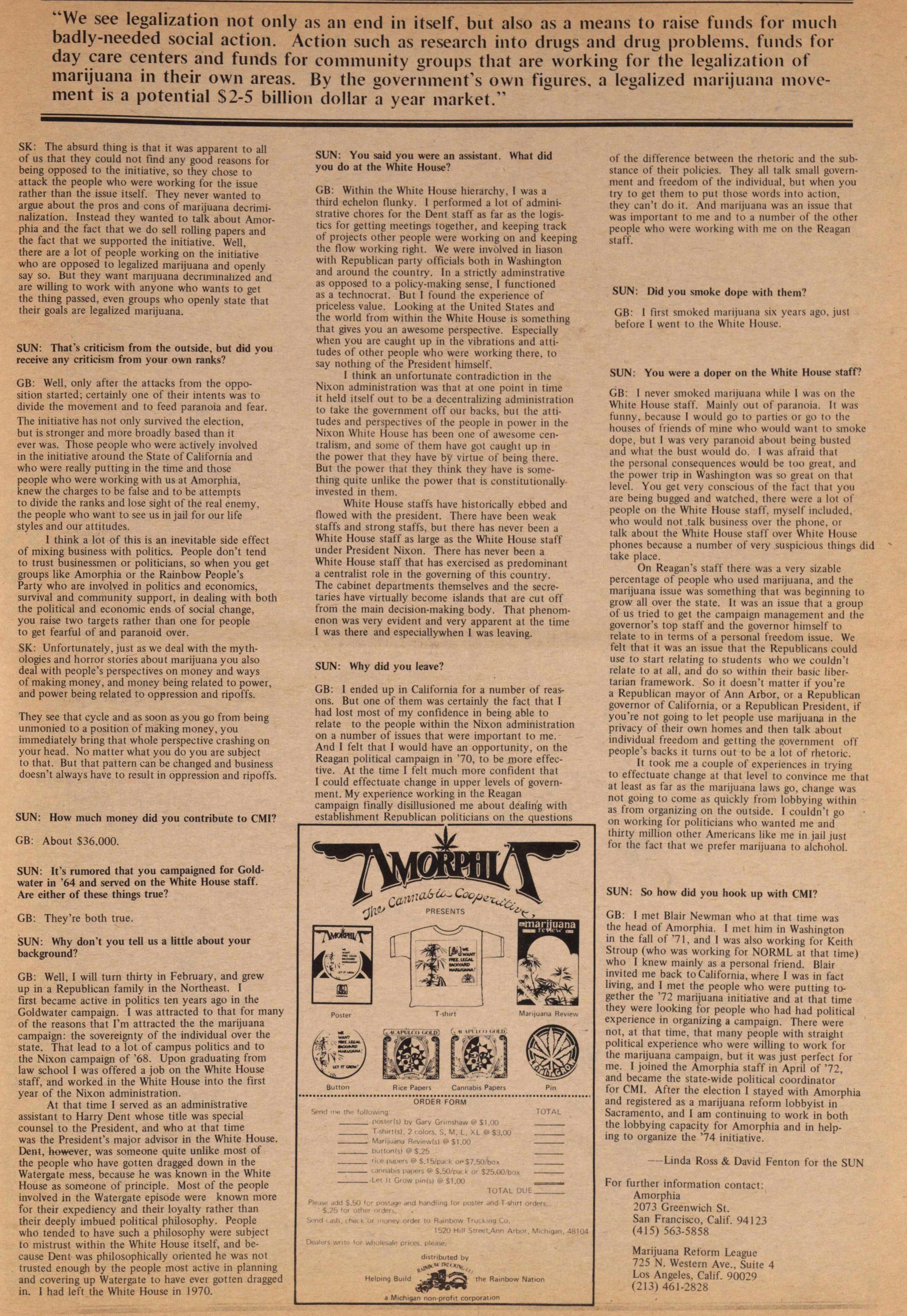

SK: This has been pretty much agreed to be the financial philosophy of the campaign. The money from all of the products that are to be sold in connection with the campaign, like t-shirts, bumper stickers, posters, and the like, will be kept in the community to be used as the community sees fit.

This is unlike the normal political campaign where the upper echelon gets a high salary and lower groups never see any of the funds.

SUN: How is the CMI being financed? SK: Right now it is being financed through whatever sales of products people have been doing since the last campaign. A lot of groups found themselves with products when the campaign ended and rather than turn them back they decided to keep selling them in order to provide money for the next campaign. And once we get going we are going to expand the product line, developing things in a more centralized basis. That is one of the areas where it pays to do things centrally, to fïnd out where in the state we can get the cheapest price for having each product produced. We'll also be getting into fund raising, but in a petition drive you can never hope for a lot of contributions. To a lot of people, they are not willing to contribute money to an issue that is not on the ballot. Even though this time they might realize that we are probably going to be on the ballot, since we were last time. There will be attempts to do other things. like benefits, and local parties for raising money.

GB: Right now our biggest income is from the sale of Acapulco Gold cigarette papers, t-shirts, the Grass Roots Gazette, and other products like pens and buttons. We have had these since the last cimpaign and so a lot of the county organizations have been able to stay alive financially through the sales of these items. These have proved to be subsistence level income products for our local branches to use.

SUN: Just what is Amorphia, and its relation to CMI?

GB: Amorphia is an organization that was originally organized fïve years ago, but really has been functioning on a national level for only the last two or three years. lts composed of a working staff of six people in San Francisco and a couple of people in New York and Michigan, consisting of either paid lobbyists, like in New York, or volunteers. John Sinclair is a volunteer in Ann Arbor working on the board of directors. Sandy and I are both members. and we've invited another woman to join to make the seventh member. but that isn't finalized yet. So the six members make up the board which discusses policy for the drive for the non-commercial legalization of marijuana. All of us involved in Amorphia either as personnel, directors, or volunteers, are people who want first and foremost a moratorium on the jailing of all people who smoke and grow marijuana, and second, the immediate development of study and research into alternative regulatory models for the supply and distribution of marijuana. We want to see the sale of marijuana become legal in the U.S. We do not want to see people who deal in marijuana go to jail, but at the same time we do not want to turn the legal marijuana market over to the large corporate interests such as alcohol and tobacco industries, or the U.S. government. Those solutions have been suggested by a lot of people, and most people who think of the legalization of marijuana immediately think of a packaged commodity like booze or cigarettes. We are trying to get people to start thinking of alternatives to that such as Alian Ginsberg's idea of having communes or cooperative selling of marijuana on a subsistence basis. Or else have persons interested in selling marijuana have a police-authorized permit to sell it like apples or oranges. We want to treat marijuana like any other vegetable or fruit or plants, but we realize the political reality that many people relate to it as something that has more in common with heroin than something that grows out of the ground like carrots or potatoes.

SUN: Isn't Amorphia a non-profit group organized to raise funds for looking into such alternatives as well as to help people understand marijuana?

GB: Right. We are incorporated under the laws of California as a non-profit organization and it's always been our premise that the people best equipped to change the marijuana laws are the users themselves. What we're trying to do is create a sense of consciousness among marijuana users that is not unlike the sense of consciousness that can be found among blacks that were trying to créate a black consciousness during the civil rights movements of the sixties. The users themselves have the capabilities of changing the marijuana laws themselves and one of the ways in which they could do that would be to support efforts to change the laws and one of the ways they could do that is to buy Amorphia products such as Acapulco Gold papers, buttons, shirts, because all of the profits go to support the legalization efforts of Amorphia. These things would include such things as persons to work for legalization, and lobbying in various states both formally and informally. We have a national membership campaign and a bi-monthly newsletter which Sandy edits; literature and brochures which we send out to persons who then become members of the cannabis cooperative. Membership is $5 a year, which we use as a sustaining donation, allowing us to send out literature all over the nation.

SUN: Didn't Amorphia give $2000 to the Michigan Marijuana Initiative and an additional $2500 to the Free John Sinclair movement? GB: Yes, most of us in Amorphia regard John Sinclair as probably the one individual in the country who has done the most and sacrificed the most as far as the legalization movement is concerned. His defense fund and the Free John Sinclair movement that resulted in the Michigan Supreme Court overturning his sentence two years ago was one of the monumental breakthroughs in the whole marijuana reform movement. There were a lot of people who were turned on to the marijuana movement and educated to the horrors and the barbaric practices of the marijuana laws by seeing someone like John Sinclair being sentenced to 10 years in prison for the possession of two joints. That is the major reason why we asked John Sinclair to the board of directors, and he right now serves as the only member of the board of directors who is outside the state of California.

SUN: If you make the ballot, what do you think your chances are of winning?

GB: Well, last year we got 34% of the vote which means we've got to change the minds of one out of five of the people who voted against us. We think we can go from 34% of the vote to somewhere in the 40-45% range. But we don't preclude the possibility of going over the top and getting over 50%. Because the marijuana issue like the war issue or the abortion issue and like the anti-pollution issue is an issue that a few years ago did not have any support at all, to speak of. But right now it is spreading like wildfire, people are changing their attitudes about marijuana more and more every day. One of the programs that Amorphia is adopting right now, is an education campaign that is aimed at conservative middle American types, trying to educate them as to the number of conservative individuals and organizations that have endorsed the legalization of marijuana, or some sort of marijuana reform within the last year or so. You have President Nixon's marijuana commission, William Buckley and other editors of National Review, the American Bar Association, the Consumers Union. Every responsible organization in research study that has been done in recent years has come out with the same recommendations about marijuana. In fact, all of the national organizations and commissions that have studied marijuana, from the Indian Hemp Commission back in 1894 through the Laguardia Commission in 1930, have all reached the conclusion that marijuana is harmless and does not cause brain damage, and does not lead to heroin and it doesn't do any of the things that the propagandists who originally made the law have been telling people to frighten them for the last thirty-five years. Fortunately there are thirty million Americans who have experimented with the drug and know firsthand that it's not the evil weed that the government has been telling them it is. But we have to reach the people who haven't used marijuana and will not use it as long as it is illegal, and reach them through means of education and make them realize that locking someone in jail for using it or growing it or even selling it is foolish, barbaric and counterproductive.

SUN: Doesn't Amorphia have projections of using marijuana commerce, if it is legalized, to raise funds for different movements around the country?

GB: Right. We see legalization not only as an end in itself, but also as a means to raise funds for much badly-needed social action. Action such as research into drugs and drug problems, funds for the founding of day care centers in communities, and funds for community groups that are working for the legalization of marijuana in their own areas. We can start using a legalized marijuana movement as a very positive force for social change. By the government's own figures, a legalized marijuana movement is a potential $2-5 billion-dollar-a-year market.

SUN: Does anyone ever call you a rip-off hip capitalist as a result of that?

SK: Sometimes the people who buy the papers and read the message that says "all proceeds are used for the legalization of marijuana" say "that can't be true, they must be a ripoff!" That's really the kind of comment that's based on paranoia. In 1972, Amorphia was accused in the media of trying to take over and control CMI, that we were the group that would most profit from the legalization of the marijuana. In other words more people would be smoking dope, therefore more people would be buying dope and papers and therefore Amorphia would "make" money.

GB: Yet the people who made those charges initially were a group called the Citizens Opposed to the Marijuana Initiative. Those people were opposed to the marijuana initiative from the outset and lashed out at Amorphia because we were the single largest financial contributer to CMI. So we were the most prominent target, even though we only numbered six people at the organizational level, a very small group compared to the governmental and corporate interests who have been supporting the marijuana laws for the last thirty-five years. "We do not want to turn the legal marijuana market over to Iarge corporate interests. We're trying to get people to think of alternatives like Allen Ginsberg's idea of having cooperative selling of marijuana on a subsistence basis.

SK: The absurd thing is that it was apparent to all of us that they could not find any good reasons for being opposed to the initiative, so they chose to attack the people who were working for the issue rather than the issue itself. They never wanted to argue about the pros and cons of marijuana decriminalization. Instead they wanted to talk about Amorphia and the fact that we do sell rolling papers and the fact that we supported the initiative. Well, there are a lot of people working on the initiative who are opposed to legalized marijuana and openly say so. But they want marijuana decriminalized and are willing to work with anyone who wants to get the thing passed, even groups who openly state that their goals are legalized marijuana.

SUN: That's criticism from the outside, but did you receive any criticism from your own ranks?

GB: Well, only after the attacks from the opposition started; certainly one of their intents was to divide the movement and to feed paranoia and fear. The initiative has not only survived the election, but is stronger and more broadly based than it ever was. Those people who were actively involved in the initiative around the State of California and who were really putting in the time and those people who were working with us at Amorphia, knew the charges to be false and to be attempts to divide the ranks and lose sight of the real enemy, the people who want to see us in jail for our life styles and our attitudes. I think a lot of this is an inevitable side effect of mixing business with politics. People don't tend to trust businessmen or politicians, so when you get groups like Amorphia or the Rainbow People's Party who are involved in politics and economics, survival and community support, in dealing with both the political and economics ends of social change, you raise two targets rather than one for people to get fearful of and paranoid over.

SK: Unfortunately, just as we deal with the mythologies and horror stories about marijuana you also deal with people's perspectives on money and ways of making money, and money being related to power, and power being related to oppression and ripoffs. They see that cycle and as soon as you go from being unmonied to a position of making money, you immediately bring that whole perspective crashing on your head. No matter what you do you are subject to that. But that pattern can be changed and business doesn't always have to result in oppression and ripoffs.

SUN: How much money did you contribute to CMI?

GB: About $36,000.

SUN: It's rumored that you campaigned for Goldwater in '64 and served on the White House staff. Are either of these things true?

GB: They're both true.

SUN: Why don't you tell us a little about your background?

GB: Well, I will turn thirty in February, and grew up in a Republican family in the Northeast. I first became active in politics ten years ago in the Goldwater campaign. I was attracted to that for many of the reasons that I'm attracted the the marijuana campaign: the sovereignty of the individual over the state. That lead to a lot of campus politics and to the Nixon campaign of '68. Upon graduating from law school I was offered a job on the White House staff, and worked in the White House into the first year of the Nixon administration. At that time I served as an administrative assistant to Harry Dent whose title was special counsel to the President, and who at that time was the President's major advisor in the White House. Dent, however, was someone quite unlike most of the people who have gotten dragged down in the Watergate mess, because he was known in the White House as someone of principie. Most of the people involved in the Watergate episode were known more for their expediency and their loyalty rather than their deeply imbued political philosophy. People who tended to have such a philosophy were subject to mistrust within the White House itself, and because Dent was philosophically oriented he was not trusted enough by the people most active in planning and covering up Watergate to have ever gotten dragged in. I had left the White House in 1970.

SUN: You said you were an assistant. What did you do at the White House?

GB: Within the White House hierarchy, I was a third echelon. I performed a lot of administrative chores for the Dent staff as far as the logistics for getting meetings together, and keeping track of projects other people were working on and keeping the flow working right. We were involved in unison with Republican party officials both in Washington and around the country. In a strictly adminstrative as opposed to a policy-making sense, I functioned as a technocrat. But I found the experience of priceless value. Looking at the United States and the world from within the White House is something that gives you an awesome perspective. Especially when you are caught up in the vibrations and attitudes of other people who were working there, to say nothing of the President himself. I think an unfortunate contradiction in the Nixon administration was that at one point in time it held itself out to be a decentralizing administration to take the government off our backs, but the attitudes and perspectives of the people in power in the Nixon White House has been one of awesome centralism, and some of them have got caught up in the power that they have by virtue of being there. But the power that they think they have is something quite unlike the power that is constitutionally invested in them. White House staffs have historically ebbed and flowed with the president. There have been weak staffs and strong staffs, but there has never been a White House staff as large as the White House staff under President Nixon. There has never been a White House staff that has exercised as predominant a centralist role in the governing of this country. The cabinet departments themselves and the secretaries have virtually become islands that are cut off from the main decision-making body. That phenomenon was very evident and very apparent at the time I was there and especially when I was leaving

SUN: Why did you leave?

GB: 1 ended up in California for a number of reasons. But one of them was certainly the fact that I had lost most of my confidence in being able to relate to the people within the Nixon administration on a number of issues that were important to me. And I felt that I would have an opportunity, on the Reagan political campaign in '70, to be more effective. At the time I felt much more confident that I could effectuate change in upper levels of government. My experience working in the Reagan campaign finally disillusioned me about dealing with establishment Republican politicians on the questions of the difference between the rhetoric and the substance of their policies. They all talk small government and freedom of the individual, but when you try to get them to put those words into action. they can't do it. And marijuana was an issue thai was important to me and to a number of the other people who were working witli me on the Reagan staff.

SUN: Did you smoke dope with them?

GB: I first smoked marijuana six years ago. just before l went to the White House.

SUN: You were a doper on the White House staff?

GB: 1 never smoked marijuana while I was on the White House staff. Mainly out of paranoia. It was funny, becarae I would go to parties or go to the houses of Iriends of mine who would want to smoke dope, but I was very paranoid about being busted and what the bust would do. I was afraid that the personal consequences would be too great. and the power trip in Washington was so great on that level. You get very conscious of the fact that you are being bugged and watched, there were a lot of people on the White House staff. myself included. who would not talk business over the phone. I talk about the White House staff over White House phones because a number of very suspicious things did - take place. On Reagan's staff there was a very sizable percentage of people who used marijuana, and the marijuana issue was something that was beginning to grow all over the state. It was an issue that a group of us tried to get the campaign management and the governor's top staff and the governor himself to relate to in terms of a personal freedom issue. We felt that it was an issue that the Republicans could use to start relating to students who we couldn't relate to at all, and do so within their basic libertarían framework. So it doesn't matter if you're a Republican mayor of Ann Arbor, or a Republican governor of California, or a Republican President, if you're not going to let people use marijuana in the privacy of their own homes and then talk about individual freedom and getting the government off people's backs it turns out to be a lot of rhetoric. It took me a couple of experiences in trying to effectuate change at that level to convince me that at least as far as the marijuana laws go, change was not going to come as quickly from lobbying within as from organizing on the outside. I couldn't go on working for politicians who wanted me and thirty million other Americans like me in jail just for the fact that we prefer marijuana to alchohol.

SUN: So how did you hook up with CMI?

GB: I met Blair Newman who at that time was the head of Amorphia. I met him in Washington in the fall of '71, and I was also working for Keith Stroup (who was working for NORML at that time) who I knew mainly as a personal friend. Blair invited me back to California, where I was in fact living, and I met the people who were putting together the '72 marijuana initiative and at that time they were looking for people who had had political experience in organizing a campaign. There were not, at that time, that many people with straight political experience who were willing to work for the marijuana campaign. but it was just perfect for me. I joined the Amorphia staff in April of '72, and became the state-wide political coördinator for CMI. After the election I stayed with Amorphia and registered as a marijuana reform lobbyist in Sacramento, and I am continuing to work in both the lobbying capacity for Amorphia and in helping to organize the '74 initiative.

For further information contact: Amorphia 2073 Greenwich St. San Francisco, CaJif. 94123 (415) 563-5858 Marijuana Reform League 725 N. Western Ave., Suite 4 Los Angeles, Calif. 90029 (213)461-2828 "We see legalization not only as an end in itself, but also as a means to raise funds for much badly-needed social action. Action such as research into drugs and drug problems, funds for day care centers and funds for community groups that are working for the legalization of marijuana in their own areas. By the government's own figures. a legalized marijuana movement is a potential $2-5 billion dollar a year market."

Article

Subjects

Freeing John Sinclair

Old News

Ann Arbor Sun