Industrial Health Hazards: The Wages of Work Can Be Death

Industrial Health Hazards:

The Wages of Work Can Be Death

Every day, American working people fight a losing battle – the battle to stay alive while earning a living. Although 71% of all workers feel that occupational health and safety are more important than wages, according to a 1969 Labor Dept. study, Industry admits that working causes 14,000 deaths annually, and 2.2 million disabling injuries. Given the enormous powers of suggestion known as “vested interest,” Industry pads its figures. The Labor Dept. estimates that the real figures are probably closer to 25,000 deaths, and 20-25 million job-related injuries, commonly called “accidents.” The work force in the U.S. now numbers about 80 million. If the Labor Dept.’s accident figures are used, this means that at least one worker in four is injured on his/her job every year.

The wages of work in this country are often death. Currently, 100,000 miners have black lung disease (pneumoconosis) from prolonged breathing of coal dust, and 4,000 die from it each year. 17,000 cotton, flax, and hemp workers have brown lung disease (byssinosis) from breathing fibrous dusts. Over the next twenty years, 6,000 uranium industry and nuclear power workers can expect to die from cancer. One out of every five asbestos workers can expect to die from cancer – almost three times the chance in the general population. In 1968, the Institute of Medicine surveyed 803 industrial and non-industrial workplaces in the Chicago area, which employed a total of a quarter million people. 73% were rated hazardous.

The situation is growing worse – and fast. In 1970, there were 6-12,000 toxic materials and chemicals in use in U.S. industries, according to the Standard Reference Manual of the Industrial Hygienists. But, there were legal toxicity standards for only 410 of them. Three thousand new chemicals are introduced every year. Any one of them could potentially prove harmful if tested. About 100 per year actually are tested. Occupational health and safety are crucial to the well-being of every American worker, and yet appallingly little service is available. Why?

For one thing, health care in the U.S. is geared almost exclusively to the treatment of acute illness. Long-term, slowly building illnesses, whose symptoms might not develop until up to 30-40 years after the initial exposure to the harmful substance, are not taken seriously until they reach a relatively critical stage. Then, the disease is very often attributed to some non-job cause. This is frequently the case with job-related heart disease, emphysema, and cancer.

Medical students spend little time studying occupational health. Doctors often ignore a person’s job, and the possibility that illnesses may be job-related. (At the Free People’s Clinic, we ask every patient if he/she works, and where, and with what, to screen for occupational hazards.) Furthermore, the vast medical industry is not value-free. Buildings, equipment, research grants, and scholarships often come from Industry, or from Government agencies whose administrators are usually drawn from the ranks of the major corporations. It is unlikely that the Ford Foundation, for instance, would look too kindly on a research proposal to study accidents, noise and dust levels at the Rouge Complex. . .

Almost all the occupational health research that is done is Industry controlled. The Industrial Health Foundation (IHF) is an “independent” research outfit that contracts its services to Big Business. The American Textile Manufacturers’ Institute commissioned IHF to study brown lung disease which often causes lung scarring and emphysema among textile workers. According to the Federal Government, brown lung afflicts 12-30% of textile workers, while it is virtually unknown in the general, non-dust-breathing population. From the IHF Report: Byssinosis is “best described as a ‘symptom-complex’ rather than a ‘disease’ in the usual sense. We feel that this term may be preferable, first, in order not to unduly alarm workers as we attempt to protect their health; and second, to help avoid unfair designation of cotton as an unduly hazardous material. . .” The Report further recommended: “It would be wise to delay temporarily the extensive and expensive changes in plant equipment and procedures aimed at dust suppression...”

The history of occupational health legislation has been spotty, at best. Between 1910 and 1920, over the strenuous objections and massive lobbying efforts of Industry, forty states passed workman’s compensation laws. While these laws do have some merit, Industry quickly readjusted its thinking, realizing that it was better to pay out the pittance due injured workers than to provide a safe workplace.

In the 1930’s, the Walsh-Healy Federal Worker Health Act was passed. It was limited to corporations which sold at least $10,000 in goods and/or services annually to the Federal Government. Although it read well, and covered 30 million workers, it provided only a pitiful $550,000 for implementation, 27 inspectors, and 5 industrial hygienists.

In recent years, there has been a rising outcry, primarily from labor unions, demanding that the Government enact strict occupational health laws with sharp enforcement teeth. There have been some victories. In 1968, when 78 West Virginia coal miners were killed in a mine explosion, the miners shut down every mine in the state until the Legislature passed a workman’s compensation law which covered black lung disease. That same year, Lyndon Johnson proposed the first comprehensive occupational health law, but the Chamber of Commerce rallied its powerful and rich lobbies and crushed the bill.

In 1970, Congress passed the Occupational Safety and Health Act, and created the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to enforce it. As usual, on paper, the law looks quite progressive. It provides for: (1) unannounced inspections of every workplace in the country, (2) worker representatives accompanying the inspectors on their tour with protection against these workers being fired, (3) mandatory inspection of any plant about which a written complaint is submitted, (4) plant closings where the inspector feels that “imminent danger” exists, but only with a court order, (5) mandatory record keeping by all companies of job-related accidents, injuries, and deaths with these files being open to the workers, and (6) a guarantee that every worker will enjoy a “safe and healthful workplace.”

However, OSHA has little real power to enforce the law. The Act provides funds for only 500 inspectors and 50 industrial hygienists for the 4.1 million workplaces in this country. Furthermore, OSHA has hired as inspectors only people with either government or industrial backgrounds, no labor people; then it contracted with Boeing Corporation for $65,000 to run a series of one-day courses to “train” the inspectors in the provisions and extent of the Act.

During the first 8 months of 1970, 17,743 workplaces were inspected. At this rate, it would take 230 years to inspect every workplace just once! Even if the number of inspectors were immediately increased to the projected number for the year 2000, it would still take 46 years to inspect every workplace once.

Neither Big Business nor the Labor Dept., which is virtually controlled by the major corporations, has ever liked OSHA. From the moment the law was passed, the Labor Dept. has badly wanted to push off all enforcement responsibilities on the states, despite a great deal of evidence that states are notoriously lax in the enforcement of such legislation. That shift has been postponed until 1976, but in the meantime, OSHA is spending a large proportion of its budget, a whopping 56% in 1972, on developing state enforcement plans.

The Labor Dept. has also knuckled under to Industry pressure in the crucial area of Standard setting. Unlike the Environmental Protections Agency, which bases pollution standards solely on public health, the Labor Dept. occupational health and safety standards take into account Industry’s assessment of “economic feasibility.” For example: Scientists generally agree that prolonged exposure to noise louder than 80 decibels (dB) is physically harmful. So the Government proposed a noise limit of 85 dB. Industry wanted a 100 dB limit! If the 100 dB Standard were put into effect, 40% of all those working at this noise level would be legally deaf in 30 years. Industry and the Labor Dept. finally settled on a noise limit of 90dB, a compromise solution which compromises workers’ health. At this level 15%, or one out of every six workers who is exposed to 90dB will become legally deaf after 30 years.

There has also been an ongoing controversy about what really constitutes “imminent danger.” In May 1971, the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers Union tried to force Allied Chemical Co. to clean up open pools of mercury at its Moundsville, West Virginia plant. The Labor Union claimed that the mercury pools constituted an “imminent danger” to worker health, and presented case histories of 25 workers who had job stations near the mercury. The workers exhibited the symptoms of mercury poisoning: tingling in hands and feet, tremors, irritability, drowsiness, sore gums, and loss of memory. Mercury poisoning can be fatal. The Labor Dept. ruled in favor of Allied Chemical, deciding that mercury poisoning was not an imminent danger. According to the Labor Dept. “imminent danger” exists only where there is “risk of sudden great harm.” However, in a bow to the Union, Allied was fined $1000 of its $40 million in annual profits.

Then, in Dec. 1971, 22 workers were blown up in an explosion at Michigan’s Port Huron Tunnel. It took the inspectors 13 days to obtain a court order closing the site because of imminent danger.

Furthermore, OSHA rules do not force companies to reveal product contents which they consider to be “trade secrets.” This basically gives Industry a carte blanche to profit from the diseases it gives its workers.

The situation is indeed grim – but not hopeless. Workers can and have organized around, and won occupational health demands. The first thing every worker must do is: find out what you work with, and if it is dangerous. The Free People’s Clinic has two books which will help you determine if your job has occupational hazards: Health Hazards in the Workplace by the Medical Committee for Human Rights (MCHR), and a new book called Work is Dangerous to Your Health by Stellman and Daum. We would also be happy to commit staff time and energy to helping workers fight for decent occupational health. The Free People’s Clinic believes that no workers should be forced to sacrifice his/her health to Industry’s insatiable appetite for ever increasing profits. Power to the workers!

– Free People’s Clinic

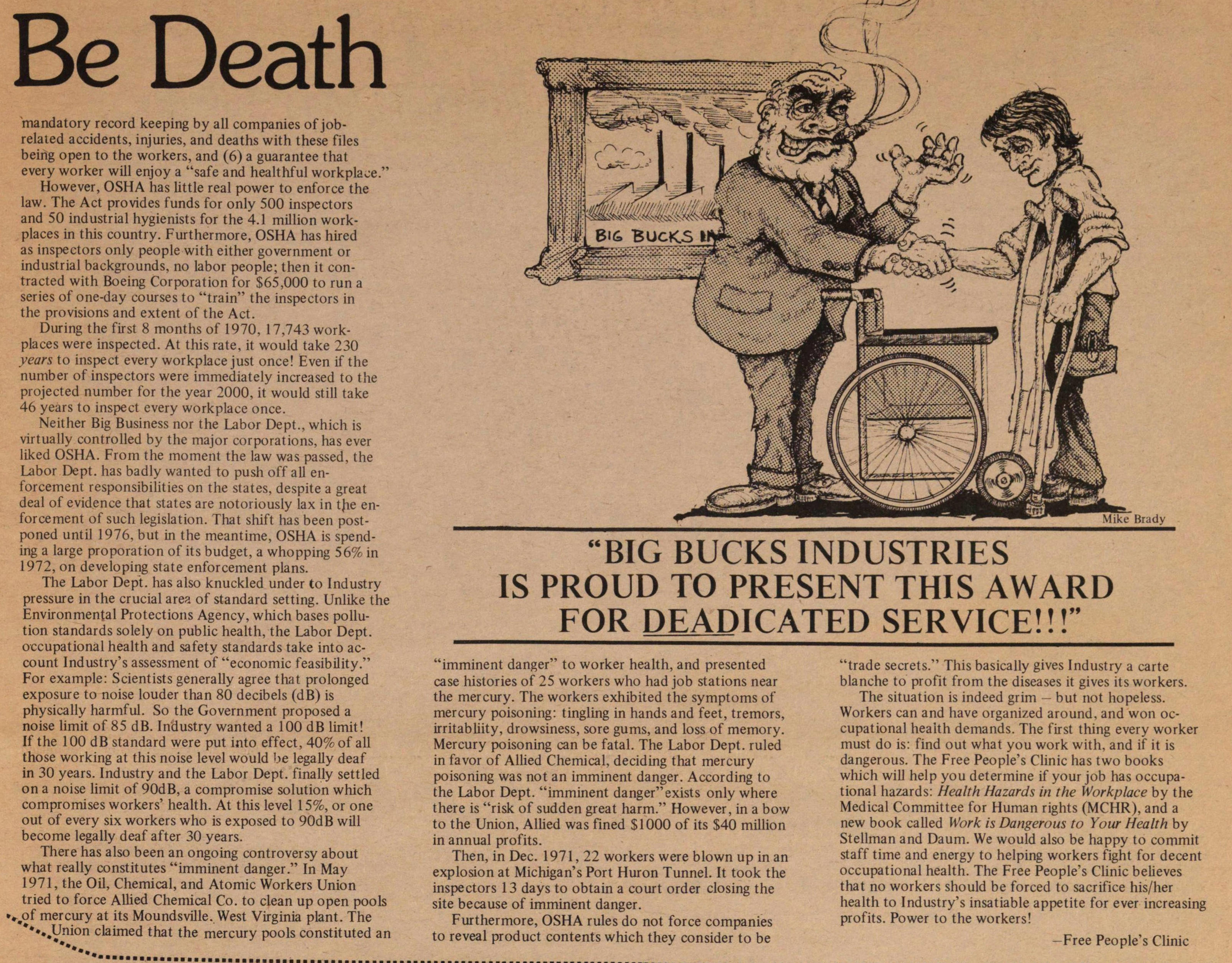

“BIG BUCKS INDUSTRIES IS PROUD TO PRESENT THIS AWARD FOR DEADICATED SERVICE!!!”

Article

Subjects

Freeing John Sinclair

Old News

Ann Arbor Sun