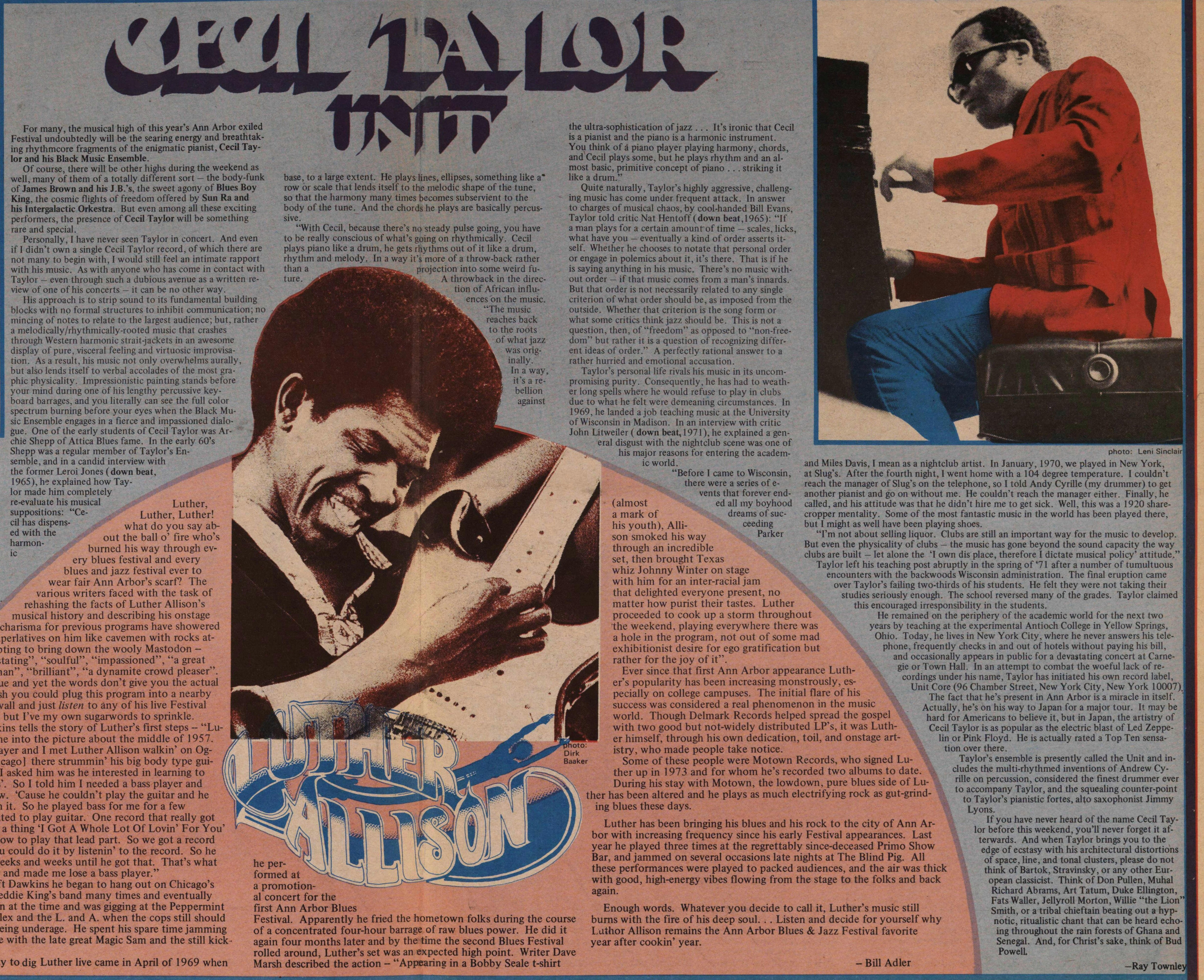

Cecil Taylor Unit

For many, the musical high this year's Ann Arbor exiled Festival undoubtedly will be the searing energy and breath taking rhythm core fragments of the enigmatic pianist, Cecil Taylor and his Black Music Ensemble.

Of course, there will be other highs during the weekend as well, many of them of a totally different sort - the body-funk of James Brown and his J.B.'s, the sweet agony of Blues Boy King, the cosmic flights of freedom offered by Sun Ra and his Intergalactic Orkestra. But even among all these exciting performers, the presence of Cecil Taylor will be something rare and special.

Personally, I have never seen Taylor in concert. And even if I didn't own a single Cecil Taylor record, of which there are not many to begin with, I would still feel an intimate rapport with his music. As with anyone who has come in contact with Taylor - even through such a dubious avenue as a written review of one of his concerts '- it can be no other way.

His approach is to strip sound to its fundamental building blocks with no formal structures to inhibit communication; no mincing of notes to relate to the largest audience; but, rather . a melodically/rhythmically-rooted music that crashes through Western harmonic strait-jackets in an awesome display of pure, visceral feeling and virtuosic improvisation. As a result, his music not only overwhelms aurally, but also lends itself to verbal accolades of the most graphic physicality. Impressionistic painting stands before your mind during one of his lengthy percussive keyboard barrages, and you literally can see the full color spectrum burning before your eyes when the Black Music Ensemble engages in a fierce and impassioned dialogue. One of the early students of Cecil Taylor was Archie Shepp of Attica Blues fame. In the early 60's Shepp was a regular member of Taylor's Ensemble, and in a candid interview with the former Leroi Jones (down beat, 1965), he explained how Taylor made him completely re-evaluate his musical suppositions: "Cecil has ed with the harmonic base, to a large extent. He plays lines, ellipses, something like a row or scale that lends itself to the melodic shape of the tune, so that the harmony many times becomes subservient to the body of the tune. And the chords he plays are basically percussive.

"With Cecil, because there's no steady pulse going, you have to be really conscious of what's going on rhythmically. Cecil plays piano like a drum, he gets rhythms out of it like a drum, rhythm and melody. In a way it's more of a throw-back rather than a projection into some weird future.

A throwback in the direction of African influences on the music. 'The music reaches back to the roots of what jazz was originally. In a way, it's a rebellion against the ultra-sophistication of jazz . . . It's ironic that Cecil is a pianist and the piano is a harmonic instrument. You think of á piano player playing harmony, chords, and Cecil plays some, but he plays rhythm and an almost basic, primitive concept of piano . . . striking it like a drum."

Quite naturally, Taylor's highly aggressive, challenging music has come under frequent attack. In answer to charges of musical chaos, by cool-handed Bill Evans, Taylor told critic Nat Hentoff (down beat, 1965): "If a man plays for a certain amount of time - scales, licks, what have you - eventually a kind of order asserts itself. Whether he chooses to notate that personal order or engage in polemics about it, it's there. That is if he is saying anything in his music. There's no music without order - if that music comes from a man 's innards. But that order is not necessarily related to any single criterion of what order should be, as imposed from the outside. Whether that criterion is the song form or what some critics think jazz should be. This is not a question, then, of "freedom" as opposed to "non-freedom" but rather it is a question of recognizing different ideas of order." A perfectly rational answer to a rather hurried and emotional accusation.

Taylor's personal life rivals his music in its uncompromising purity. Consequently, he has had to weather long spells where he would refuse to play in clubs due to what he felt were demeaning circumstances. In 1969, he landed a job teaching music at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. In an interview with critic John Litweiler ( down beat, 1971), he explained a general disgust with the nightclub scene was one of his major reasons for entering the academic world.

"Before I came to Wisconsin, there were a series of events that forever ended all my boyhood dreams of succeeding Parker and Miles Davis, I mean as a nightclub artist. In January, 1970, we played in New York, at Slug's. After the fourth night, I went home with a 104 degree temperature. I couldn't reach the manager of Slug's on the telephone, so l told Andy Cyrille (my drummer) to get another pianist and go on without me. He couldn't reach the manager either. Finally, he called, and his attitude was that he didn't hire me to get sick. Well, this was a 1920 sharecropper mentality. Some of the most fantastic music in the world has been played there, but I might as well have been playing shoes.

"I'm not about selling liquor. Clubs are still an important way for the music to develop. I But even the physicality of clubs - the music has gone beyond the sound capacity the way clubs are built - let alone the 'I own dis place, therefore I dictate musical policy' attitude"

Taylor left his teaching post abruptly in the spring of '71 after a number of tumultuous encounters with the backwoods Wisconsin administration. The final eruption carne over Taylor's failing two-thirds of his students. He felt they were not taking their studies seriously enough. The school reversed many of the grades. Taylor claimed this encouraged irresponsibility in the students.

He remained on the periphery of the academic world for the next two years by teaching at the experimental Antioch college in Yellow Springs Ohio. Today he lives in New York City, where he never answers his telephone, frequently checks in and out of hotels without paying his bill, and occasionally appears in public for a devastating concert at Carnegie or Town Hall in an attempt to combat the woeful lack of recordings under his name, Taylor has initiated his own record label, Unit Core(96 Chamber Street New York, New York 10007)

The fact that he's present in Ann Arbor is a miracle in itself .

Actually, he's on his way to Japan for a major tour. It may be hard for Americans to believe it, but in Japan, the artistry of Cecil Taylor is as popular as the electric blast of Led Zeppelin or Pink Floyd. He is actually rated a Top Ten sensation over there.

Taylor's ensemble is presently called the Unit and includes the multi-rhymed inventions of Andrew Cyrille on percussion, considered the finest drummer to accompany Taylor, and the Squealing counter to Taylor's pianistic fortes, alto saxophonist Jim Lyons.

If you have have never heard the name of the name Cecil Taylor before this weekend forget it afterwards.And when Taylor brings you to the edge of ecstasy with his architectural distortions of space, line, and tonal clusters, please do not thank of Bartok, Stravinsky, or any other European classicist. Think of Don Pullen, Muhal Richard Abram, Art Tatum, Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, Jellyroll Morton. Wille "the Lion Smith, or a tribal Chieftain beating out a hypnotic, ritualistic chant that can be heard echoing in throughout the rain forests of Ghan and Senegal. And, for Christ's sake, think of Bud Powell.

---Ray Townley

Article

Subjects

Freeing John Sinclair

Old News

Ann Arbor Sun