B.B. King

B.B. King

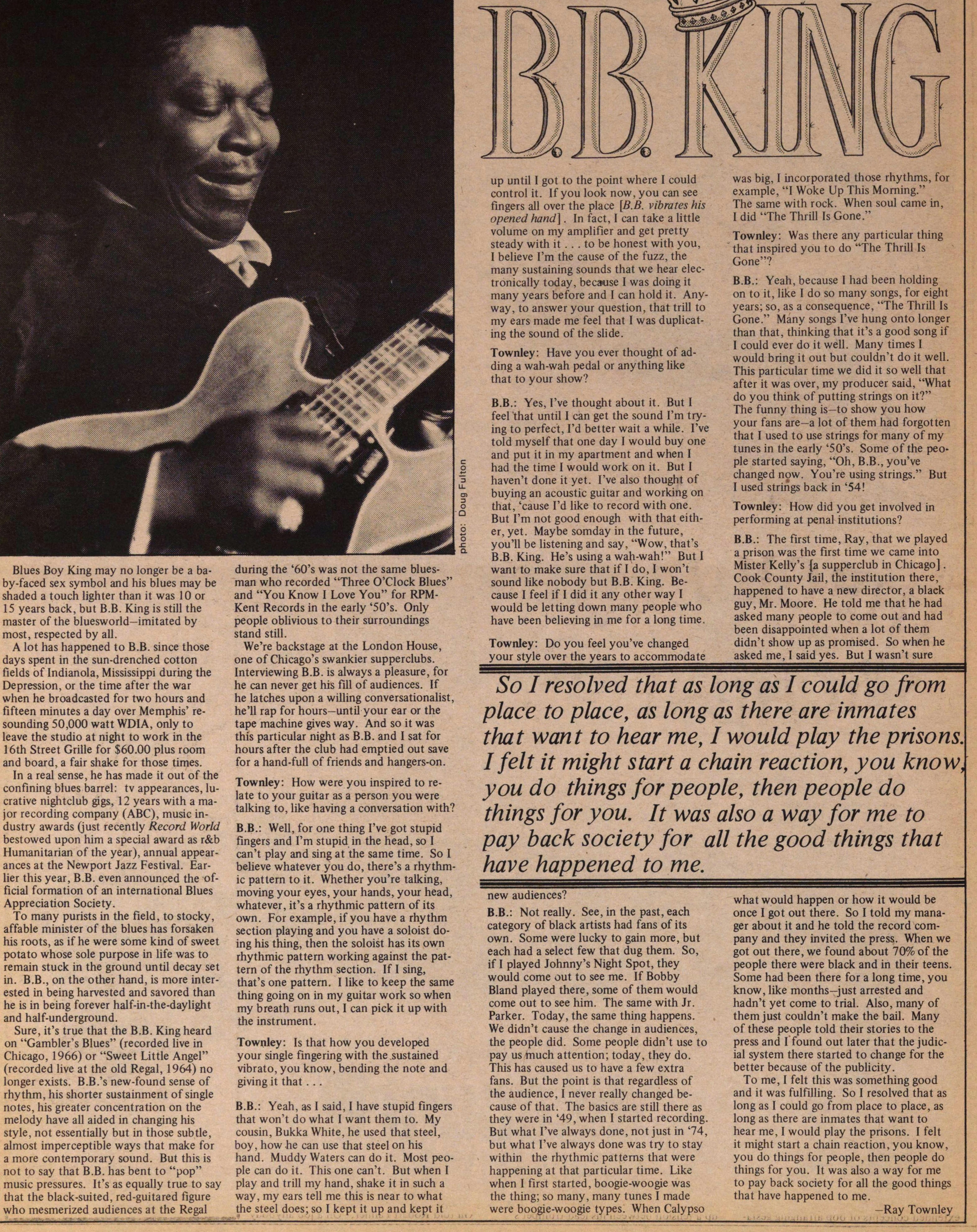

Blues Boy King may no longer be a baby-faced sex symbol and his blues may be shaded a touch lighter than it was 10 or 15 years back, but B.B. King is still the master of the bluesworld- imitated by most, respected by all.

A lot has happened to B.B. since those days spent in the sun-drenched cotton fields of Indianola, Mississippi during the Depression, or the time after the war when he broadcasted for two hours and fifteen minutes a day over Memphis' resounding 50,000 watt WDIA, only to leave the studio at night to work in the 16th Street Grille for $60.00 plus room and board, a fair shake for those times.

In a real sense, he has made it out of the confining blues barrel: tv appearances, lucrative nightclub gigs, 12 years with a major recording company (ABC), music industry awards (just recently Record World bestowed upon him a special award as r&b Humanitarian of the year), annual appearances at the Newport Jazz Festival. Earlier this year, B.B. even announced the official formation of an international Blues Appreciation Society.

To many purists in the field, to stocky, affable minister of the blues has forsaken his roots, as if he were some kind of sweet potato whose sole purpose in life was to remain stuck in the ground until decay set in. B.B., on the other hand, is more interested in being harvested and savored than he is in being forever half-in-the-daylight and half-underground.

Sure, it's true that the B.B. King heard on "Gambler's Blues" (recorded live in Chicago, 1966) or "Sweet Little Angel" (recorded live at the old Regal, 1964) no longer exists. B.B. 's new-found sense of rhythm, his shorter sustainment of single notes, his greater concentration on the melody have all aided in changing his style, not essentially but in those subtle, almost imperceptible ways that make for a more contemporary sound. But this is not to say that B.B. has bent to "pop" music pressures. It's as equally true to say that the black-suited, red-guitared figure who mesmerized audiences at the Regal during the '60's was not the same bluesman who recorded "Three O'Clock Blues" and "You Know I Love You" for RPMKent Records in the early '50's. Only people oblivious to their surroundings stand still.

We're backstage at the London House, one of Chicago's swankier supperclubs. Interviewing B.B. is always a pleasure, for he can never get his fill of audiences. If he latches upon a willing conversationalist, he'll rap for hours-until your ear or the tape machine gives way. And so it was this particular night as B.B. and I sat for hours after the club had emptied out save for a hand-full of friends and hangers-on.

Townley: How were you inspired to relate to your guitar as a person you were talking to, like having a conversation with?

B.B.: Well, for one thing I've got stupid fingers and I'm stupid in the head, so I can't play and sing at the same time. So I believe whatever you do, there's a rhythmic pattern to it. Whether you're talking, moving your eyes, your hands, your head, whatever, it's a rhythmic pattern of its own. For example, if you have a rhythm section playing and you have a soloist doing his thing, then the soloist has its own rhythmic pattem working against the pattern of the rhythm section. If I sing, that's one pattern. I like to keep the same thing going on in my guitar work so when my breath runs out, I can pick it up with the Instrument.

Townley: Is that how you developed your single fingering with the sustained vibrato, you know, bending the note and giving it that . . .

B.B.: Yeah, as I said, I have stupid fingers that won't do what I want them to. My cousin, Bukka White, he used that steel, boy, how he can use that steel on his hand. Muddy Waters can do it. Most people can do it. This one can't. But when I play and trill my hand, shake it in such a way, my ears teil me this is near to what the steel does; so I kept it up and kept it up until I got to the point where I could control it. If you look now, you can see fingers all over the place [B.B. vibrares his opened hand] . In fact, I can take a little volume on my amplifier and get pretty steady with it . . . to be honest with you, I believe I'm the cause of the fuzz, the many sustaining sounds that we hear electronically today, because I was doing it many years before and I can hold it. Anyway, to answer your question, that trill to my ears made me feel that I was duplicating the sound of the slide.

Townley: Have you ever thought of adding a wah-wah pedal or anything like that to your show?

B.B.: Yes, l've thought about it. But I feel that until I can get the sound I'm trying to perfect, l'd better wait a while. l've told myself that one day I would buy one and put it in my apartment and when I had the time I would work on it. But I haven't done it yet. l've also thought of buying an acoustic guitar and working on that, 'cause l'd like to record with one. But I'm not good enough with that either, yet. Maybe somday in the future, you'll be listening and say, "Wow, that's B.B. King. He's using a wah-wah!" But I want to make sure that if I do, I won't sound like nobody but B.B. King. Because I feel if I did it any other way I would be letting down many people who have been believing in me for a long time.

Townley: Do you feel you've changed your style over the years to accommodate new audiences?

B.B.: Not really. See, in the past,each category of black artists had fans of its own. Some were lucky to gain more, but each had a select few that dug them. So, if I played Johnny's Night Spot, they would come out to see me. If Bobby Bland played there, some of them would come out to see him. The same with Jr. Parker. Today, the same thing happens. We didn't cause the change in audiences, the people did. Some people didn't use to pay us much attention; today, they do. This has caused us to have a few extra fans. But the point is that regardless of the audience, I never really changed because of that. The basics are still there as they were in '49, when I started recording. But what I've always done, not just in '74, but what I've always done was try to stay within the rhythmic patterns that were happening at that particular time. Like when I first started, boogie-woogie was the thing; so many, many tunes I made were boogie-woogie types. When Calypso was big, I incorporated those rhythms, for example, "I Woke Up This Morning." The same with rock. When soul came in, I did "The Thrill Is Gone."

Townley: Was there any particular thing that inspired you to do "The Thrill Is Gone"?

B.B.: Yeah, because I had been holding on to it, like I do so many songs, for eight years; so, as a consequence, "The Thrill Is Gone." Many songs I've hung onto longer than that, thinking that it's a good song if I could ever do it well. Many times I would bring it out but couldn't do it well. This particular time we did it so well that after it was over, my producer said, "What do you think of putting strings on it?" The funny thing is-to show you how your fans are- a lot of them had forgotten that I used to use strings for many of my tunes in the early '50's. Some of the people started saying, "Oh, B.B., you've changed now. You're using strings." But I used strings back in '54!

Townley: How did you get involved in performing at penal institutions?

B.B.: The first time, Ray, that we played a prison was the first time we carne into Mister Kelly's [a supperclub in Chicago]. Cook County Jail, the institution there, happened to have a new director, a black guy, Mr. Moore. He told me that he had asked many people to come out and had been disappointed when a lot of them didn't show up as promised. So when he asked me, I said yes. But I wasn't sure what would happen or how it would be once I got out there. So I told my manager about it and he told the record company and they invited the press. When we got out there, we found about 70% of the people there were black and in their teens. Some had been there for a long time, you know, like months- just arrested and hadn't yet come to trial. Also, many of them just couldn't make the bail. Many of these people told their stories to the press and I found out later that the judicial system there started to change for the better because of the publicity.

To me, I felt this was something good and it was fulfilling. So I resolved that as long as I could go from place to place, as long as there are inmates that want to hear me, I would play the prisons. I felt it might start a chain reaction, you know, you do things for people, then people do things for you. It was also a way for me to pay back society for all the good things that have happened to me.

--Ray Townley

Article

Subjects

Freeing John Sinclair

Old News

Ann Arbor Sun