Midland Nuke Plant Radiates Scandal

According to a 1965 Atomic Energy Commission study, a nuclear plant accident could result in 45,000 deaths, 100,000 injuries and fallout blanketing an area the size of Pennsylvania. Marred by quality control scandals, such a nuclear plant is rising in Midland, Michigan, just ninety miles north of Ann Arbor

by David Stoll

A year ago this month, the SUN ran a story by Detroit newsman Pat Clawson exposing radiation leaks at the Consumer’s Power nuclear plant at South Haven. Following the SUN’s release of the story, a former Palisades technician living in Ann Arbor made public memorandums detailing yet another radiation leakage problem at the Palisades plant, this time from waste storage tanks.

The memos resulted in charges that Consumer’s had tried to cover-up the problem, AEC and Justice Dept. investigations and a $19,000 civil fine for Consumer’s, as well as a further round of charges that the Justice Dept. had been pressured into making a less than thorough investigation.

Because the Palisades plant has remained shut down – for 16 months now – the focus of the anti-nuclear struggle in Michigan has drifted to another plant, the huge 1600 megawatt Consumer’s plant rising in Midland.

A 400 ton nuclear reactor arrived in Midland, Michigan Nov. 27, by rail at two miles an hour. It is to be planted in the billion dollar Consumer’s Power project, a twin reactor nuclear plant to generate steam and electricity.

The Midland plant is also the subject of a nuclear controversy, one of a number strung across the country like so many burning ponderosas. Last month the controversy received fresh impetus, after six years of fight. A small number of workmen on the Midland site told the SUN that quality assurance testing of the plant’s construction was still being abused. Their charges could halt further work, as well as lend weight to the movement to stop the nuclear station entirely.

The SUN didn’t immediately realize the significance of the workers’ charges but other people did. When Nucleonics Week, the newsletter of the atomic industry, heard about the workers’ charges, it gave them its lead. Lawyers for anti-nuke citizen groups offered names of officials, phone numbers and advice. The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) declared its willingness to investigate. A Consumer’s Power official pronounced himself “mystified”, but the workers’ charges really weren’t very mysterious, nor were their possible consequences.

According to the workers, AEC-required quality control tests had been omitted, negative results ignored and improper testing procedures followed (see SUN, Dec. 6). The abuses centered, they said, on landfill for holding pond dikes and concrete being poured into the nuclear core containment.

At stake is the safety of the plant, and thousands of lives. Called into question is the plant’s ability to contain radiation, sustain external shock and maintain its supply of water to cool the hot nuclear core.

The AEC has shut down construction at Midland for quality control violations before, but not for long. This is because the AEC is at least as interested in promoting nuclear power as regulating it.

A HISTORY OF UNREDEEMED PROMISES

Consumer’s record on quality control at the Midland plant is sinful and long, dating back to when the plant’s construction began in 1970, but the utility wasn’t taken to task by the AEC until last December.

“What we have here,” foamed the AEC in an extraordinary memorandum, “is a pattern of repeated, flagrant and significant quality assurance violations of a non-routine character – coupled with an unredeemed promise of reformation.”

AEC Atomic Safety and Licensing boards don’t use that kind of language very often, but in this case the board was aroused enough to get Midland construction halted on Dec. 4, 1973, mostly for improper welding and sloppy testing of the concrete foundation work.

Thirteen days later construction resumed, however and according to workers a year later, any improvement has been only a sham.

Consumer’s quality control habits assume even greater significance because of the awful example of the Palisades plant, its decaying masterwork at South Haven.

Since August 1973 Palisades has been closed because of corroding steam tubes, a vibrating nuclear core and radiation leaks into Lake Michigan and the atmosphere. Besides being the prototype of the Midland plant, the Palisades plant was built by the same architect-engineer now working at Midland. This is the Bechtal Corp., a construction firm headquartered in San Francisco, said to be working on all seven continents and employing 1,100 persons in the Ann Arbor area.

Palisades has corroded, leaked and vibrated so badly, in fact, that over the summer Consumer’s launched a $300 million suit against Bechtel and three other contractors for their work on the plant. Damages were sought for poor quality parts, materials and negligence in construction.

But despite contrary reports, Consumer’s continues to maintain that Bechtel has reformed and all is well at the Midland plant.

If the AEC substantiates the Midland workers’ charges, the most immediate result will probably be an order to temporarily suspend construction. There are larger movements afoot, however, which could have even greater consequences.

Within recent months:

*the Saginaw Intervenors have argued before the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C. that Consumer’s construction license granted two years ago should be revoked, on the grounds the licensing procedure excluded many safety and environmental issues.

*the Public Service Commission and the Saginaw Intervenors, a citizen’s group, have both asked the AEC to decide whether Bechtel’s record at Palisades merits halting work at Midland. Another quality control scandal could lead to Bechtel’s permanent debarment from the site.

HIDEOUS STRENGTH

The fight against the Midland plant has been led by the Saginaw Intervenors, whose mostly unpublicized struggle has become one of the vanguard anti-nuke efforts in the country. When Nucleonics Weekly revealed in 1971 that the AEC couldn't make its critical Emergency Core Cooling System (ECCS) work, it was at the Midland construction license hearings that a citizens' group first insisted it be raised as an issue. The ECCS proceeded to reverbate through every license hearing across the country, and an Intervenor's appeal finally resulted in national nuclear safety hearings in Washington, D.C.

President and mainstay of the Saginaw group is Mary Sinclair, a determined woman who teaches a course on nuclear power at the University of Michigan's Residential College. Ms. Sinclair has been a science writer for Dow Chemical Company and the Library of Congress. She first came to Ann Arbor in 1970 to study the nuclear issue, and last year completed a degree in Environmental Communications with the School of Natural Resources.

Legal bludgeon man for the Intervenors is a Chicago corporate attorney named Myron Cherry, a moving agent in the Palisades controversy as well as at Midland.

"Offending officers of Consumer’s Power (ought to be) indicted and tried for criminal violations of the Atomic Energy Act," Cherry said recently in a typical statement. He has become notorious for his harrassment of Consumer's and AEC officials, as well as his tips to newspersons.

The Midland hearings took a year and a half to finish, but they seem to have functioned mostly as a line of defense against environmentalist issues. During the hearings, says Cherry, the AEC refused to allow the Intervenors to cross-examine the authors of the environmental impact report, question and evacuation plan or raise the issue of the utility's quality control record. Now Consumer's is close to leading the nation's Utilities in quality control and safety violations. Another anti-nuclear coup could soon be scored with the Intervenors' suit against Consumer's in the U.S. Appeals Court. Besides Consumer's massive investment in the Midland plant, the Intervenors' suit also challenges the AEC's hearing rules.

Their task is made more difficult by the fact that Intervenors have to raise their own money and hire their own legal talent. The right lawyers aren't easy to find, costs quickly run into the tens of thousands of dollars and access to proceedings are severely limited by AEC rules.

"Catch-22 stuff, you know," Cherry told the SUN.

TEA AND SYMPATHY

But while environmental arguments are still mostly inadmissable in AEC hearings, quality control of construction is another thing. Since construction began, the AEC's regional office in Chicago has been earnestly trying to enforce its complex, stringent regulations. By the time violations reach the agency's higher realms, however, there is still a great deal of sympathy for the Utility's problems, its economic necessities and the status quo.

Last December after quality control violations shut down the plant, for example, the AEC's director of regulation, L. Manning Numtzing, met with two Midland bankers, the director of the Midland Chamber of Commerce and a leading minister. The meeting was arranged by Midland's Congressman, Rep. E.A. Cederberg, a ranking Republican on the House Appropriations Committee and a backer of the nuclear plant.

According to participants, Muntzing told the Midland businessmen that the hearing necessary to reopen the plant "would go away”. Although Muntzing denied the report, what did go away was the order stopping construction, seven days later. AEC inspectors had steered the utility through an announced inspection prior to the meeting, and when the hearing was finally held the next summer, AEC inspectors said there were no longer any quality control problems at the site. Lacking money and independent experts, the Intervenors failed to contest the proceeding. Consumer's turned the hearing into a show-case for the nuclear future.

THE CITY OF DOW

The nuclear power controversy has staggering consequences for the future, but the fight over the Midland plant is no popular struggle. Midland itself, a small industrial city and a one company town, is best described as the home of the Dow Chemical Company. 10,000 people work for the Dow company in a city of 30,000, and a four month strike against the company this summer gave the town an early taste of depression.

The only time Midland citizens have demonstrated for or against the plant was at a massive pro-nuclear rally in the summer of 1971, during the license hearings. The rally was promoted by the Chamber of Commerce, hosted, by Art Linkletter and addressed by Rep. Cederberg and Senator Robert Griffin. Dow employees were let off from work early to attend the rally, then were set to signing a giant mock-up of the construction license.

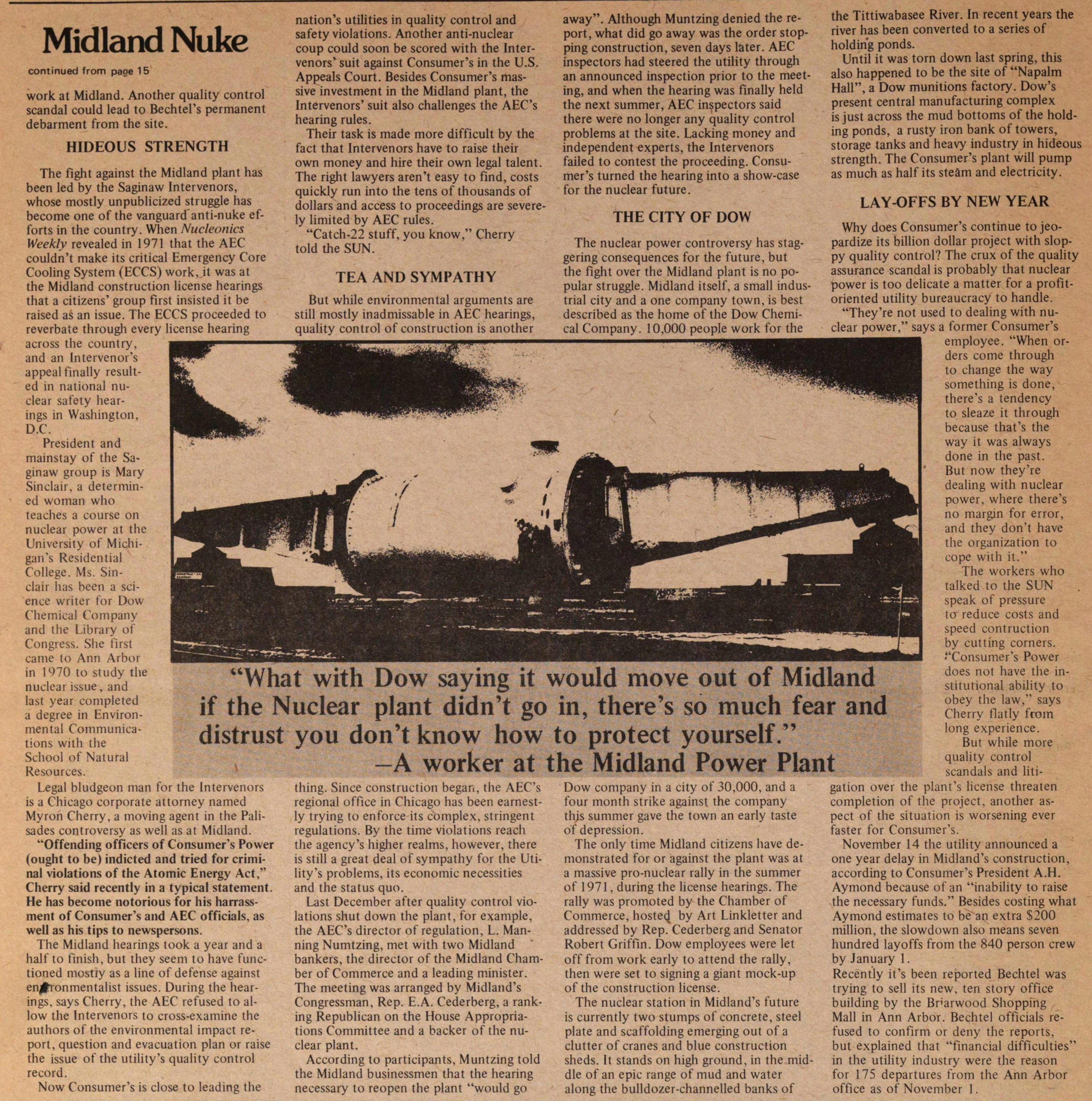

The nuclear station in Midland's future is currently two stumps of concrete, steel plate and scaffolding emerging out of a clutter of cranes and blue construction sheds. It stands on high ground, in the middle of an epic range of mud and water along the bulldozer-channelled banks of the Tittiwabasee River. In recent years the river has been converted to a series of holding ponds.

Until it was torn down last spring, this also happened to be the site of "Napalm Hall", a Dow munitions factory. Dow's present central manufacturing complex is just across the mud bottoms of the holding ponds, a rusty iron bank of towers, storage tanks and heavy industry in hideous strength. The Consumer's plant will pump as much as half its steam and electricity.

LAY-OFFS BY NEW YEAR

Why does Consumer's continue to jeopardize its billion dollar project with sloppy quality control? The crux of the quality assurance scandal is probably that nuclear power is too delicate a matter for a profit-oriented utility bureaucracy to handle.

"They're not used to dealing with nuclear power," says a former Consumer's employee. "When orders come through to change the way something is done, there's a tendency to sleaze it through because that's the way it was always done in the past. But now they're dealing with nuclear power, where there's no margin for error, and they don't have the organization to cope with it."

The workers who talked to the SUN speak of pressure (o reduce costs and speed contruction by cutting corners. "Consumer's Power does not have the institutional ability to obey the law," says Cherry flatly from long experience.

But while more quality control scandals and litigation over the plant 's license threaten completion of the project, another aspect of the situation is worsening ever faster for Consumer's.

November 14 the utility announced a one year delay in Midland's construction, according to Consumer's President A.H. Aymond because of an "inability to raise the necessary funds." Besides costing what Aymond estimates to be an extra $200 million, the slowdown also means seven hundred layoffs from the 840 person crew by January 1.

Recently it's been reported Bechtel was trying to sell its new, ten story office building by the Briarwood Shopping Mall in Ann Arbor. Bechtel officials refused to confirm or deny the reports, but explained that "financial difficulties" in the utility industry were the reason for 175 departures from the Ann Arbor office as of November 1.

"What with Dow saying it would move out of Midland if the Nuclear plant didn't go in, there's so much fear and distrust you don't know how to protect yourself."

- A worker at the Midland Power Plant

Article

Subjects

Freeing John Sinclair

Old News

Ann Arbor Sun