Interview With Herbie Hancock Buddhist Chanting And The High Road To Success

Interviewed by Bill Adler and David Fenton. Written and edited by Bill Adler

Composer/keyboard wizard Herbie Hancock is currently the number one selling jazz artist in the World. His Columbio album "Head Hunters" was the first jazz album in the history of the music business to be awarded a gold album, that is, sell $1 million worth of records at the retail level. The album that followed it , "Thrust" is doing equally well. However, things weren 't always quite so plush for Herb.

His professional career began in 1960 when the then-20-year-old pianist joined trumpeter Donald Byrd's group. He began to record with other established jazz luminaries including altoist Jackie McLean and genius composermidti-reedist Eric Dolphy. In 1962 Hancock recorded his first album as a leader for Blue Note Records which included a tune he wrote entitled "Watermelon Man" which "Was just something I felt I had to do to sell my album. I didn't respect that tune about a year after that." Nevertheless, "Watermelon Man "did, in fact, become a smash r&b hit for percussionist Mongo Santamaria who recorded it soon after Herbie.

Hancock 's talent and fame grew throughout the jazz world in the Sixties. He was a member of Miles Davis' units from 1964 until 1969, including a performance on the epochal "In a Silent Way. " During that time he was in constant demand as a sideman on other folk's dates, and he began to write numerous movie soundtrack scores including the one for Antonioni's "Blow-Up." His dates as a leader showcased an ever more colorful and inventivc ensemble arranger.

In 1970 Hancock left Blue Note for Warner Bros. whose roster is comprised almost exclusively of rock artists. Herbie's music became increasingly electronic and more demanding of the listener. Although his critical and popular acclaim had never been greater, Herbie, in 1972, was still finding it difficult to keep his head above water financially.

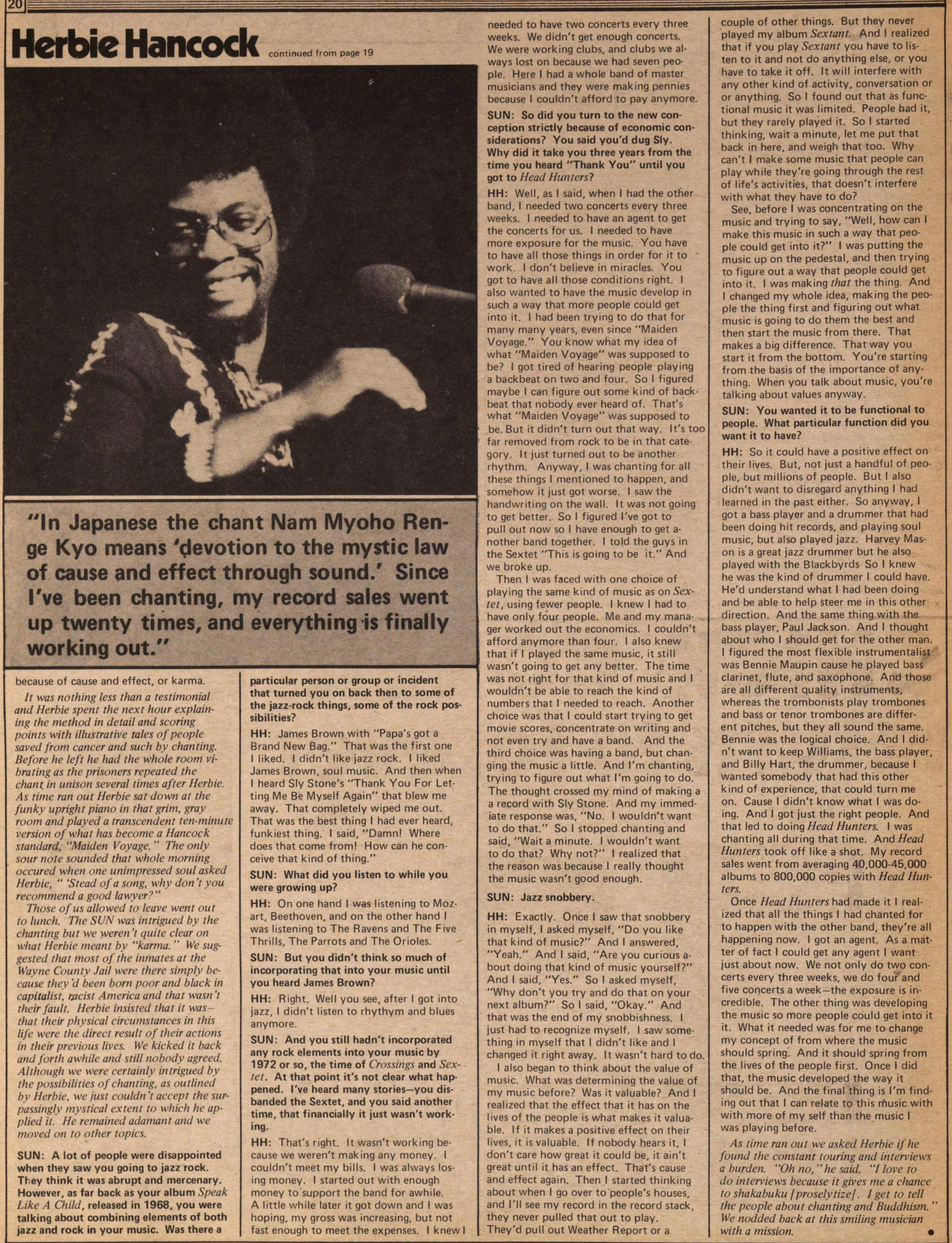

The next time we heard from our man it was 1974. He was playing distinctive, outrageously funky, jazz-rock with a new band on a new album entitled "Head Hunters. " The rest is history.

Herbie stopped in Detroit during a regional promotional tour on February 18, four days before he and his group were to perform in Ann Arbor at Hill Auditorium.

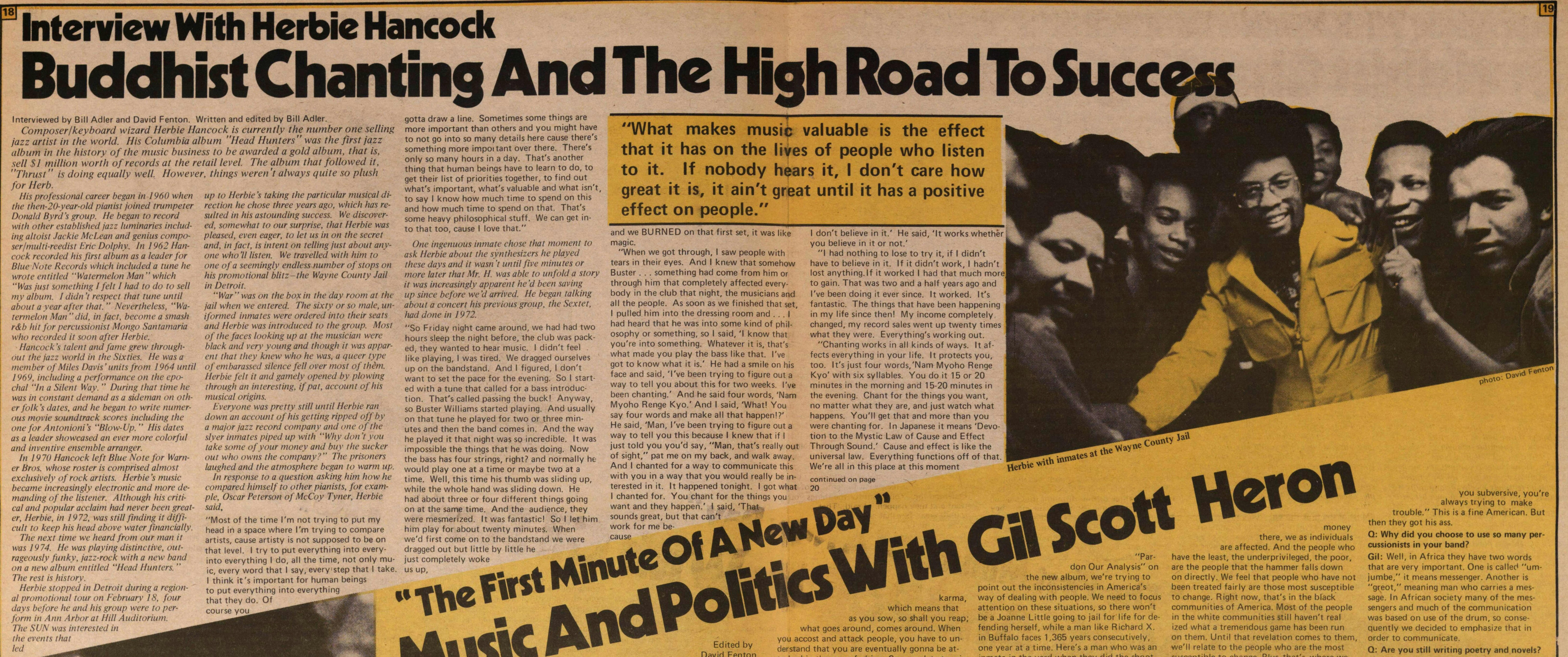

The SUN was interested in the events that led up to Herbie's taking the particular musical direction he chose three years ago, which has resulted in his astounding success. We discovered, somewhat to our surprise, that Herbie was pleased, even eager, to let its in on the secret and, infact, is inent on telling just about anyone who'll listen. We travelled with him to one of a seemingly endless number of stops on his promotional blitz-the Wayne County Jail in Detroit.

"War" was on the box in the day room at the jail when we entered. The sixty or so male, uniformed inmates were ordered into their seats and Herbie was introduced to the group. Most of the faces looking up at the musician were black and very young and though it was apparent that they knew who he was, a queer type of embarrassed silence fell over most of them. Herbie felt it and gamely opened by plowing through an interesting, if pat, account of his musical origins.

Everyone was pretty still until Herbie ran down an account of his getting ripped off by a major jazz record company and one of the slyer inmates piped up with "Why don't you take some of your money and buy the sucker out who owns the company?" The prisoners laughed and the atmosphere began to warm up.

In response to a question asking him how he compared himself to other pianists, for example, Oscar Peterson of McCoy Tyner, Herbie said,

"Most of the time l'm not trying to put my head in a space where l'm trying to compare artists, cause is not supposed to be on that level. I try to put everything into everyinto everything I do, all the time, not only muic every word that I say, everystep that I take. I think it's important for human beings to put everything into everything that they do. Of course you gotta draw a line. Sometimes some things are more important than others and you might have to not go into so many details here cause there's something more important over there. There's only so many hours in a day. That's another thing that human beings have to learn to do, to get their list of priorities together, to find out what's important, what's valuable and what isn't, to say I know how much time to spend on this and how much time to spend on that. That's some heavy philosophical stuff. We can get nto that too, cause I love that."

One ingenuous inmate chose that moment to ask Herbie about the synthesizers he played these days and it wasn't until five minutes or more later that Mr. H. was able to unfold a story it was increasingly apparent he'd been saving up since before we d arrived. He began talking about a concert his previous group, the Sextet, had done in 1972.

"So Friday night came around, we had had two hours sleep the night before, the club was packed, they wanted to hear music. I didn't feel like playing, I was tired. We dragged ourselves up on the bandstand. And I figured, I don't want to set the pace for the evening. So I started with a tune that called for a bass introduction. That's called passing the buck! Anyway, so Buster Williams started playing. And usually on that tune he played for two or three minutes and then the band comes in. And the way he played it that night was so incredible. It was impossible the things that he was doing. Now the bass has four strings, right? and normally he would play one at a time or maybe two at a time. Well, this time his thumb was sliding up, while the whole hand was sliding down. He had about three or four different things going on at the same time. And the audience, they were mesmerized. It was fantastic! So I let him him play for about twenty minutes. When we'd first come on to the bandstand we were dragged out but little by little he just completely woke us up, and we BURNED on that first set, it was like magic.

"When we got through, I saw people with tears in their eyes. And I knew that somehow Buster...something had come from him or through him that completely affected everybody in the club that night, the musicians and all the people. As soon as we finished that set, I pulled him into the dressing room and...I had heard that he was into some kind of philosophy or something, so I said, 'I know that you're into something. Whatever it is, that's what made you play the bass like that. l've got to know what it is.' He had a smile on his face and said, 'l've been trying to figure out a way to tell you about this for two weeks, l've been chanting.' And he said four words, 'Nam Myoho Renge Kyo.' And I said, 'What! You say four words and make all that happen!?' He said, 'Man, l've been trying to figure out a way to tell you this because I knew that if I just told you you'd say, "Man, that's really out of sight," pat me on my back, and walk away. And I chanted for a way to communicate this with you in a way that you would really be interested in it. It happened tonight. I got what I chanted for. You chant for the things you want and they happen. I said, That sounds great, but that can't work for me because I don't believe in it.' He said, 'It works whether you believe in it or not.'

"I had nothing to lose to try it, if I didn't have to believe in it. If it didn't work, I hadn't lost anything. lf it worked I had that much more to gain. That was two and a half years ago and l've been doing it ever since. It worked. It's fantastic. The things that have been happening in my life since then! My income completely changed, my record sales went up twenty times what they were. Everything's working out.

"Chanting works in all kinds of ways. It affects everything in your life. It protects you, too. It's just four words,'Nam Myoho Renge Kyo' with six syllables. You do it 15 or 20 minutes in the morning and 15-20 minutes in the evening. Chant for the things you want, no matter what they are, and just watch what happens. You'll get that and more than you were chanting for. In Japanese it means 'Devotion to the Mystic Law of Cause and Effect Through Sound.' Cause and effect is like the universal law. Everything functions off of that. We're all in this place at this moment because of cause and effect, or karma.

It was nothing less than a testimonial and Herbie spent the next hour explaining the method in detail and scoring points with illustrative tales of people saved from cancer and such by chanting. Befare he left he had the whole room vibrating as the prisoners repeated the chant, in unison several times after Herbie. As time ran out Herbie sat down at the funky upright piano in that grim, gray room and played a transcendent ten-minute version of what has become a Hancock standard, "Maiden Voy age." The only sour note sounded that whole morning occured when one unimpressed soul asked Herbie, " 'Stead of a song, why don 't you recommend a good lawyer? "

Those of us allowed to leave went out to lunch. The SUN was intrigued by the chanting but we weren't quite clear on what Herbie mesmi by "karma. " We suggested that most of the inmates at the Wayne County Jail were there simply because they'd been born poor and black in capitalist, racist America and that wasn't their fault. Herbie insisted that it was that their physical circumstances in this life were the direct result of their actions in their previous lives. We kicked it back and forth awhile and still nobody agreed. Although we were certainly intrigued by the possibilities of chanting, as outtined by Herbie, we just couldn 't accept the surpassingly mystical extent to which he applied it. He remained adaman t and we moved on to other topics.

SUN: A lot of people were disappointed when they saw you going to jazz rock. They think it was abrupt and mercenary. However, as far back as your album Speak Like A Child, released n 1968, you were talking about combining elements of both jazz and rock in your music. Was there a particular person or group or incident that turned you on back then to some of the jazz-rock things, some of the rock possibilities?

HH: James Brown with "Papa's got a Brand New Bag." That was the first one I liked. I didn't like jazz rock. I liked James Brown, soul music. And then when I heard Sly Stone's 'Thank You For Letting Me Be Myself Again" that blew me away. That completely wiped me out. That was the best thing I had ever heard, funkiest thing. I said, "Damn! Where does that come from! How can he conceive that kind of thing."

SUN: What did you listen to while you were growing up?

HH: On one hand I was listening to Mozart, Beethoven, and on the other hand I was listening to The Ravens and The Five Thrills, The Parrots and The Orioles.

SUN: But you didn't think so much of incorporating that into your music until you heard James Brown?

HH: Right. WelI you see, after I got into jazz, I didn't listen to rhythym and blues anymore.

SUN: And you still hadn't incorporated any rock elements into your music by 1972 or so, the time of Crossings and Sextet. At that point it's not clear what happened. l've heard many stories- you disbanded the Sextet, and you said another time, that f inancially it just wasn't working.

HH: That's right. It wasn't work ing because we weren't making any money. I couldn't meet my bilis. I was always losing money. I started out with enough money to'support the band for awhile. A little while later it got down and I was hoping, my gross was increasing, but not fast enough to meet the expenses. I knew I needed to have two concerts every three weeks. We didn't get enough concerts. We were working clubs, and clubs we always lost on because we had seven peopie. Here I had a whole band of master musicians and they were making pennies because I couldn't afford to pay anymore.

SUN: So did you turn to the new conception strictly because of economie consideratíons? You said you'd dug Sly. Why did it take you three years from the time you heard "Thank You" until you got to Head Hunters?

HH: Well, as I said, when I had the other band, I needed two concerts every three weeks. I needed to have an agent to get the concerts for us. I needed to have more exposure for the music. You have to have all those things in order for t to work. I don't believe in miracles. You got to have all those conditions right. I also wanted to have the music develop in such a way that more people could get into t. I had been trying to do that for many many years, even since "Maiden Voyage." You know what my idea of what "Maiden Voyage" was supposed to be? I got tired of hearing people playing a backbeat on two and four. So I figured maybe I can figure out some kind of backbeat that nobody ever heard of. That's what "Maiden Voyage" was supposed to be. But it didn't turn out that way. It's too far removed from rock to be in that category. It just turned out to be another rhythm. Anyway, I was chanting for all these things I mentioned to happen, and somehow t just got worse. I saw the handwriting on the wall. It was not going to get better. So I figured l've got to pull out now so I have enough to get another band together. I told the guys in the Sextet "This is going to be it." And we broke up.

Then I was faced with one choice of playing the same kind of music as on Sextet, using fewer people. I knew I had to have only four people. Me and my manager worked out the economics. I couldn't afford anymore than four. I also knew that if I played the same music, it still wasn't going to get any better. The time was not right for that kind of music and I wouldn't be able to reach the kind of numbers that I needed to reach. Another choice was that I could start trying to get movie scores, concentrate on writing and not even try and have a band. And the third choice was having a band, but changing the music a little. And l'm chanting, trying to figure out what l'm going to do. The thought crossed my mind of making a a record with Sly Stone. And my immediate response was, "No. I wouldn't want to do that." So I stopped chanting and said, "Wait a minute. I wouldn't want to do that? Why not?" I realized that the reason was because I really thought the music wasn't good enough.

SUN: Jazz snobbery.

HH: Exactly. Once I saw that snobbery in myself, I asked myself, "Do you like that kind of music?" And I answered, "Yeah." And I said, "Are you curious about doing that kind of music yourself?" And I said, "Yes." So I asked myself, "Why don't you try and do that on your next album?" So I said, "Okay." And that was the end of my snobbishness. I just had to recognize myself. I saw something in myself that I didn't like and I changed it right away. It wasn't hard to do. I also began to think about the value of music. What was determining the value of my music before? Was it valuable? And I realized that the effect that it has on the lives of the people is what makes t valuable. If it makes a positive effect on their lives, it is valuable. If nobody hears it, I don't care how great it could be, it ain't great until it has an effect. That's cause and effect again. Then I started thinking about when I go over to people's houses, and l'll see my record in the record stack, they never pulled that out to play. They'd pull out Weather Report or a couple of other things. But they never played my album Sextant. And I realized that if you play Sextant you have to listen to t and not do anything else, or you have to take t off. It will interfere with any other kind of activity, conversation or or anything. So I found out that as functional music it was limited. People had t, but they rarely played it. So I started thinking, wait a minute, let me put that back in here, and weigh that too. Why can't I make some music that people can play while they're going through the rest of life's activities, that doesn't interfere with what they have to do?

See, before I was concentrating on the music and trying to say, "Well, how can I make this music in such a way that people could get into it?" I was putting the music up on the pedestal, and then trying to figure out a way that people could get into it. I was making that the thing. And I changed my whole idea, making the people the thing first and figuring out what music is going to do them the best and then start the music from there. That makes a big difference. That way you start it from the bottom. You're starting from the basis of the importance of anything. When you talk about music, you're talking about values anyway.

SUN: You wanted it to be functional to people. What particular function did you want it to have?

HH: So it could have a positive effect on their lives. But, not just a handful of people, but millions of people. But I also didn't want to disregard anything I had learned in the past either. So anyway, I got a bass player and a drummer that had been doing hit records, and playing soul music, but also played jazz. Harvey Mason is a great jazz drummer but he also played with the Blackbyrds So I knew he was the kind of drummer I could have. He'd understand what I had been doing and be able to help steer me in this other direction. And the same thing with the bass player, Paul Jackson. And I thought about who I should get for the other man. I figured the most flexible instrumentalist was Bennie Maupin cause he played bass clarinet, flute, and saxophone. And those are all different quality nstruments, whereas the trombonists play trombones and bass or tenor trombones are different pitches, but they all sound the same. Bennie was the logical choice. And I didn't want to keep Williams, the bass player, and Billy Hart, the drummer, because I wanted somebody that had this other kind of experience, that could turn me on. Cause I didn't know what I was doing. And I got just the right people. And that led to doing Head Hunters. I was chanting all during that time. And Head Hunters took off like a shot. My record sales went from averaging 40,000-45,000 albums to 800,000 copies with Head Hunters.

Once Head Hunters had made it I realized that all the things I had chanted for to happen with the other band, they're all happening now. I got an agent. As a matter of fact I could get any agent I want just about now. We not only do two concerts every three weeks, we do four and five concerts a week- the exposure is ncredible. The other thing was developing the music so more people could get into it it. What it needed was for me to change my concept of from where the music should spring. And it should spring from the lives of the people first. Once I did that, the music developed the way it should be. And the final thing is l'm finding out that I can relate to this music with with more of my self than the music I was playing before.

As time ran out we asked Herbie if he found the constant touring and interviews a burden. "Oh no,"he said. "I love do interviews because it gives me a chance to shakabuku (proselytize). I get to tell the people about chanting and Buddhism. " We nodded back at this smiling musician with a mission.

"In Japanese the chant Nam Myoho Ren ge Kyo means 'devotion to the mystic law of cause and effect through sound Since l've been chanting, my record sales went up twenty times, and everything is finally working out."

Article

Subjects

Freeing John Sinclair

Old News

Ann Arbor Sun