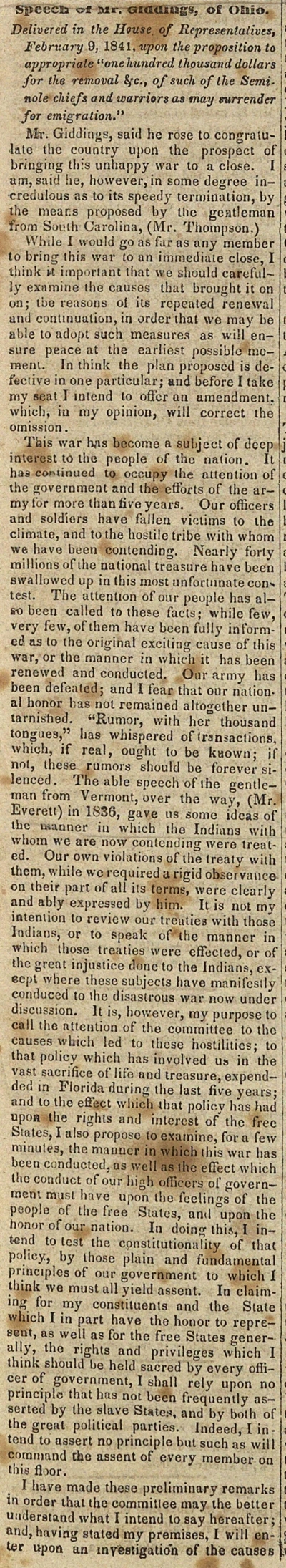

Speech Of Mr. Giddings, Of Ohio: Delivered In The House Of R...

Mr. Giddings, said he rose to congratulate the country upon the prospect of bringing this unhappy war to a close. I am, said he, however, in some degree incredulous as to its speedy termination, by the means proposed by the gentleman from South Carolina, (Mr. Thompson.)

While I would go as far as any member to bring this war to an immediate close, I think it important that we should carefully examine the causes that brought it on on; the reasons of its repeated renewal and continuation, in order that we may be able to adopt such measures as will ensure peace at the earliest possible moment. In think the plan proposed is defective in one particular; and before I take my seat I intend to offer an amendment. which, in my opinion, will correct the omission.

This war his become a subject of deep interest to the people of the nation. It has continued to occupy the attention of the government and the efforts of the army for more than five years. Our officers and soldiers have fallen victims to the climate, and to the hostile tribe with whom we have been contending. Nearly forty millions of the national treasure have been swallowed up in this most unfortunate contest. The attention of our people has also been called to these facts; while few, very few, of them have been fully informed as lo the original exciting cause of this war, or the manner in which it has been renewed and conducted. Our army has been defeated; and I fear that our national honor has not remained altogether untarnished. Rumor, with her thousand tongues, has whispered of transactions, which, if real, ought to be known; if not, these rumors should be forever silenced. The able speech of the gentleman from Vermont, over the way, (Mr. Everett) in 1836, gave us some ideas of the manner in which the Indians with whom we are now contending were treated. Our own violations of the treaty with them, while we required a rigid observance on their part of all its terms, were clearly and ably expressed by him. It is not my intention to review our treaties with those Indians, or to speak of the manner in which those treaties were effected, or of the great injustice done to the Indians, except where these subjects have manifestly conduced to the disastrous war now under discussion. It is, however, my purpose to call the attention of the committee to the causes which led to these hostilities: to that policy which has involved us in the vast sacrifice of life and treasure, expend-ded in Florida during the last five years; and to the effect which that policy has had upon the rights and interest of the free States, I also propose to examine, for a few minutes, the manner in which this war has been conducted, as well as the effect which the conduct of our high officers of government must have upon the feelings of the people of the free States, and upon the honor of our nation. In doing this, I intend to test the constitutionality of that policy, by those plain and fundamental principles of our government to which I think we must all yield assent. In claiming for my constituents and the State which I in part have the honor to represent, as well as for the free States generally, the rights and privileges which I think should be held sacred by every officer of government, I shall rely upon no principle that has not been frequently asserted by the slave States, and by both of the great political parties. Indeed, I intend to assert no principle but such as will command the assent of every member on this floor.

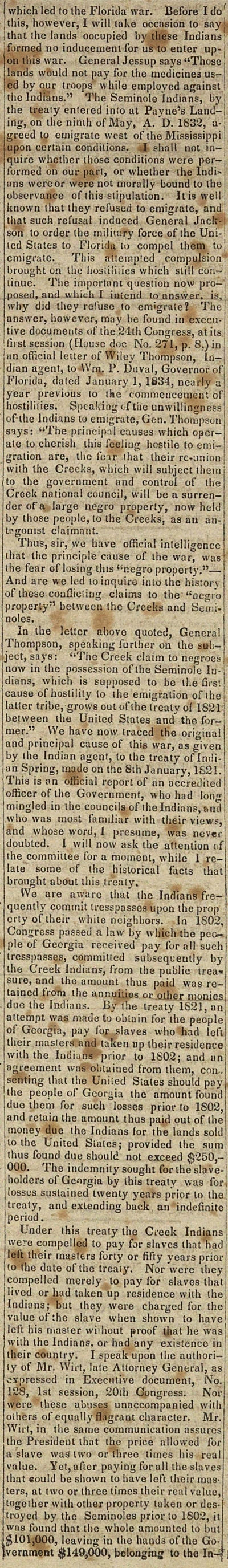

I have made these preliminary remarks in order that the committee may the better understand what I intend to say hereafter; and,having stated my premises, I will enter upon an investigation of the causes which led to the Florida war. Before I do this, however, I will take occasion to say that the lands occupied by these Indians formed no inducement for us to enter upon this war. General Jessup says "Those lands would not pay for the medicines used by our troops while employed against the Indians." The Seminole Indians, by the treaty entered into at Payne's Landing, on the ninth of May, A. D. 1832, agreed to emigrate west of the Mississippi upon certain conditions. I shall not inquire whether those conditions were performed on our part, or whether the Indians were or were not morally bound to the observance of this stipulation. It is well known that they refused to emigrate, and that such refusal induced General Jackson to order the military force of the United States to Florida to compel them to emigrate. This attempted compulsion brought on the hostilities which still continue. The important question now proposed, and which I intend to answer. is, is why did they refuse to emigrate? The answer, however, may be found in executive documents of the 24th Congress, at its first session (House doc No. 271, p. 8.) in an official letter of Wiley Thompson, Indian agent, to Wm. P. Duval, Governor of Florida, dated January 1, 1834, nearly a year previous to the commencement of hostilities. Speaking of the unwillingness of the Indians to emigrate, Gen. Thompson says: "The principal causes which operate to cherish this feeling hostile to emigration are, the that their reunion with the Creeks, which will subject them to the government and control of the Creek national council, will be a surrender of a large negro property, now held by those people, to the Creeks, as an antagonist claimant. Thus, sir, we have official intelligence that the principle cause of the war, was the fear of losing this "negro property." . And are we led to inquire into the history of these conflicting claims to the "negro property" between the Creeks and Seminoles.

In the letter above quoted, General Thompson, speaking further on the subject, says: "The Creek claim to negroes now in the possession of the Seminole Indians, which is supposed to be the first cause of hostility lo the emigration of the latter tribe, grows out of the treaty of 1821 between the United States and the former." We have now traced the original and principal cause of this war, as given by the Indian agent, to the treaty of Indian Spring, made on the 8th January, 1821. This is an official report of an accredited officer of the Government, who had long mingled in the councils of the Indians, and who was most familiar with their views, and whose word, I presume, was never doubted. I will now ask the attention of the committee for a moment, while I relate some of the historical facts that brought about this treaty.

We are aware that the Indians frequently commit tresspasses upon the property of their white neighbors. In 1802, Congress passed a law by which the people of Georgia received pay for all such tresspasses, committed subsequently by the Creek Indians, from the public treasure, and the amount thus paid was retained from the annuities or other monies due the Indians. By the treaty 1821, an attempt was made to obtain for the people of Georgia, pay for slaves who had left their masters and taken up their residence with the Indians prior to 1802; and an agreement was obtained from them, consenting that the United States should pay the people of Georgia the amount found due them for such losses prior to 1802, and retain the amount thus paid out of the money due the Indians for the lands sold to the United States; provided the sum thus found due should not exceed $250,000. The indemnity sought for the slaveholders of Georgia by this treaty was for losses sustained twenty years prior to the treaty, and extending back an indefinite period.

Under this treaty the Creek Indians were compelled to pay for slaves that had left their masters forty or fifty years prior to the date of the treaty. Nor were they compelled merely to pay for slaves that lived or had taken up residence with the Indians; but they were charged for the value of the slave when shown to have left his master without proof that he was with the Indians, or had any existence in their country. I speak upon the authority of Mr. Wirt, late Attorney General, as expressed in Executive document, No. 128, 1st session, 20th Congress. Nor were these abuses unaccompanied with others of equally flagrant character. Mr. Wirt, in the same communication assures the President Unit the price allowed for a slave was two or three times his real value. Yet, after paying for all the slaves that would be shown to have left their musters, at two or three times their real value, together with other property taken or destroyed by the Seminoles prior to 1802, it was found that the whole amounted to but $101,000, leaving in the hand of the Government $149,000, belonging to the Indians. This money, however, was not returned to the Indians, but was retained by government until 1834, when the owners of the fugitive slaves petitioned Congress that it might be divided among them. - This petition was referred to the Committee on Indian affairs, and the Chairman, an honorable member from Georgia, (Mr. Gilmer,) reported in favor of dividing the money among the owners of the fugitive slaves as a compensation for the offspring which the slaves would have borne had they remained in bondage. This plan, which I think sets at perfect defiance all Yankee calculations, was rejected by Congress. But a bill was subsequently introduced, providing for a division of this money among the owners of those slaves by way of interest, in direct violation of the treaty, and notwithstanding they had previously received two or three times the real value of their slaves; and this bill soon passed into a law. This was done in 1834. These slaves had most of them united with the Seminoles or runaways in the peninsula of Florida, and the Creeks, (from whom the Seminoles had formerly separated) having paid to the people of Georgia two or three times the value of those slaves, now claimed them as their property. The Creeks had mostly gone west of the Mississippi and their agents were in Florida demanding these negroes of the Seminoles. The Seminoles, in the mean time, it is said, had intermarried with the negroes, and stood connected with them in all the relations of domestic life. - If they emigrated west, their wives and children would be taken from them by the Creeks as slaves; if they remained in Florida, they must defend themselves against the army of the United States. - With them, sir, it was war on one side and slavery on the other. This state of things was entirely brought about by the efforts of our government to obtain pay for the fugitive slaves of Georgia.

This interference of the Federal Government in behalf of slavery in Georgia, appears to have been the origin of all our Florida difficulties.

[Mr. Warren, of Georgia, called Mr. Giddings to order on the ground of irrelevancy. The Chairman, Mr. Clifford, of Maine, decided that the remarks of Mr. Giddings respecting the origin of the Florida war were in order; and Mr. G. proceeded.]

I think this interposition of our Federal Government unconstitutional and improper, and will assign the reasons of that opinion.

[Mr. Habersham, of Georgia, called Mr. Giddings to order, and stated the gentleman from Ohio had intimated his intention to offer an amendment to the proposition before the House, and was proceeding to make a speech pretty freely interlarded with abolition, while this committee were yet uninformed as to the terms of the amendment he intended to offer. The Chairman stated that the remarks of the gentleman from Ohio had reference to the proposition before the House, and were therefore in order. Mr. Habersham desired to hear the amendment.]

Mr. Giddings resumed. I arose Mr. Chairman, to discuss the Florida war, and I intend doing so, and cannot be drawn off upon any collateral points, nor frightened from it by the cry of abolition.

I will, however, say to the gentleman from Georgia, that I have not said, nor do I intend saying one word upon the subject of abolition, although I may perhaps touch upon the doctrine of State rights and strict construction.

[To be continued.

Article

Subjects

Vermont

United States

South Carolina

Seminole Indians

Payne's Landing

Ohio

Mississippi

Georgia

Florida

Creeks

Signal of Liberty

Old News

Wm. P. Duval

Wiley Thompson

Mr. Wirt

Mr. Warren

Mr. Thompson

Mr. Habersham

Mr. Gilmer

Mr. Giddings

Mr. Everett

Mr. Clifford

General Jessup

General Jackson