The Pingree Street Sixteen Go On Trial

Detroit’s Smack: Police Domain?

Three years ago Willie B. Foster, currently of Jackson Prison, blew away part of Wiley Reed's jaw with a shotgun. Nonetheless Mr. Reed recently offered a considerable flow of sworn testimony in Detroit's Recorder's Court in a trial that continues as one of the most controversial and explosive in the city's history.

Reed's subject involved the recent past, but how his story is finally received may have something to do with how the struggling Motor City deals with its troubled present and a future that often seems darkly uncertain.

A 35-year-old ex-convict and former heroin addict, Reed says he started at $900 a week in 1971 as a delivery man, bodyguard and factotum for one of the kingpins of Detroit's flourishing heroin subculture, 36-year-old Milton "Happy" Battle. Apparently Reed earned his money. In addition to the point-blank shotgun blast that altered his jaw, he says he was shot at on four other occasions and had two hand grenades tossed at him.

Having survived all of this, he finally decided it might be more sensible to become a police informer. A debatable proposition in any case, in this instance it became even more so, since the information he supplied helped lead to the indictments of a dozen Detroit police officers along with 16 of Reed's former cohorts in an allegedly wide-ranging and lucrative drug ring reputedly headed by "Happy" Battle from 1968 to 1973.

As he waited to testify in the trial of the Pingree Street Conspiracy, as the case has become known in Detroit, (jury selection started in May and the trial itself opened on July 3rd) Reed, sequestered and closely guarded somewhere in another city, must have wondered how many on both sides of the law might like to see his vital functions permanently terminated and might yet try to accomplish that purpose.

To avoid such an event security for the trial in Judge Justin Ravitz's specially remodeled and enlarged courtroom in the basement of the Hall of Justice has been unprecedented in Detroit. During the preliminary hearing which continued for several months through the summer and fall of 1973, rumors and threats of assassination attempts against Reed and other key witnesses were heard repeatedly. And in fact two of the 16 civilians originally indicted in May of 1973 will never stand trial. They've been murdered in the interim.

In all, with charges dropped against some of those indicted and deals made with others, nine policemen and seven civilians are now on trial in the Pingree Street case. Whenever police officers are accused of breaking the law, feelings run high. And with three white sergeants and six patrolmen, two white and four black, accused of conspiring to sell heroin and cocaine and to take bribes and obstruct justice, there have been frequent cries of "frameup" and "fix" from within the Detroit Police Department. But there may be more at stake here than the careers, reputations, and perhaps freedom of nine cops.

JUNK & DETROIT

Over the past several years, particularly since the riot in 1967, Detroit has been plagued by its thriving traffic in illicit narcotics. Current "official" figures list the city as second only to New York in the per-capita rate of heroin addiction among its residents. An estimated 50 thousand junkies spend more than a million dollars a day on their "jones," the city's street term for heroin. And the county medical examiner says two-thirds of the homicides in the "Murder Capital" are linked in some way with dope.

Drug-related crime continues to send whites and businesses fleeing to the suburbs from a city already 50 percent black and hard hit by unemployment. Those who must stay behind have tried to escape the ambience of the pusher by moving and shifting within the city in such drives that once-fine neighborhoods have been left rotting and deserted. The solace of jones and the Horatio Alger lure of selling it threatens to engulf a generation of ghetto young people. And those who keep tabs on the problem in Detroit say they see no signs of the situation peaking or leveling off.

Mayor Coleman Young says the causes are obvious and basically two-fold: economic crisis conditions (with 40% unemployment among young blacks in the city) and widespread police corruption allowing easy availability to breed increasing addiction.

The mayor's efforts to stir an economic up-turn in the city have run afoul of a disasterous period for its crucial auto industry, and his plans to reorganize the Detroit Police (to achieve a modicum of racial parity in a department 85% white) have frequently met with derision and hostility from many white cops in the department.

It is against this background that the possible significance of the Pingree Street Conspiracy trial begins to emerge. For the case represents an unprecedented effort on the part of the police department to clean its own house and at the same time put the city's often brazen drug merchants on notice that there won't be any place to hide from now on.

Some knowledgeable observers are saying the situation may be comparable to a grand jury investigation conducted in the early forties by Circuit Judge (and later U.S. Senator) Homer Ferguson, which sent several top city and police officials to prison for their connections with gambling activities in Detroit. Rumors abound that if convictions result in the Pingree Street case and certain people start talking, the scandal may reach into the administrative offices on the third floor of police headquarters at 1300 Beaubien.

POLICE DETAIL 318

The roots of the investigation that resulted in the current trial reach back to 1971 when then-police commissioner John Nichols was persuaded by Vincent Piersante of the attorney general's organized crime division and by representatives of New Detroit, Inc. to name George Bennett, a black police force veteran of 21 years, to probe persistent reports of widespread drug dealing and police payoffs on Detroit 's west side.

Bennett, then a lieutenant, had recently gained noteriety by charging in a lawsuit against the department that he had been a victim of racism on the force. And Nichols, as the trial's initial prosecution witness, testified that he chose Bennett not only for his "integrity and honesty" but also because he was likely to command the respect of the department's young black officers.

In December of 1971 Bennett and a hand-picked squad of three men (later more men were added) known as Detail 318 launched their investigation in the 10th (Livernois) precinct. For two years Bennett and his men worked without public notice, although behind the scenes it was apparently anything but quiet at times as Bennett, frustrated by what he felt was a lack of cooperation from Nichols and others in the department, went to then-Mayor Roman Gribbs and secured the assistance of Philip Tannian, a Gribbs aide at the time, and Roy Hayes, head of the Wayne County Organized Crime Task Force.

Finally, in January 1973, Bennett and Hayes began taking witnesses before a Wayne County Citizens Grand Jury. In their indictments handed down after several months of deliberation the jury members charged both cops and civilians with conspiring to sell, deliver or possess narcotics and conspiring to obstruct justice. Under the latter charge they referred to activities such as murder, castration, bribery, and kidnapping. And at the same time they named 23 others as co-conspirators unindicted because they had agreed to testify against the defendants.

At this point in the summer of 1973 charges and counter-charges began flying in Detroit, and they haven't stopped since. George Bennett was publically accused of attempting to frame the white officers involved out of racist revenge and of using his investigative position for personal aggrandizement. The department's Internal Affairs section charged that its own investigation of Bennett and Detail 318 had turned up evidence of irregular if not illegal activity, for example, the complaint of a grand jury witness that he had been plied with marijuana and "forced" by two of Bennett's men to testify about police corruption.

Bennett in turn charged that the work of his unit had been subject to "harassment, intimidation, and threats." He had been told by reliable sources, he said, that a contract had been put out on his life from within the department offering $20,000 and a one-way plane ticket anywhere. Commissioner Nichols authorized 24-hour police protection for Bennett and his family and later promoted him to inspector. Since Mayor Young took office in January l74 Bennett has enjoyed the full support of Young's appointed police chief Philip Tannian, who in the past year and a half has raised Bennett from inspector to commander to deputy chief.

SHOOTING GALLERIES

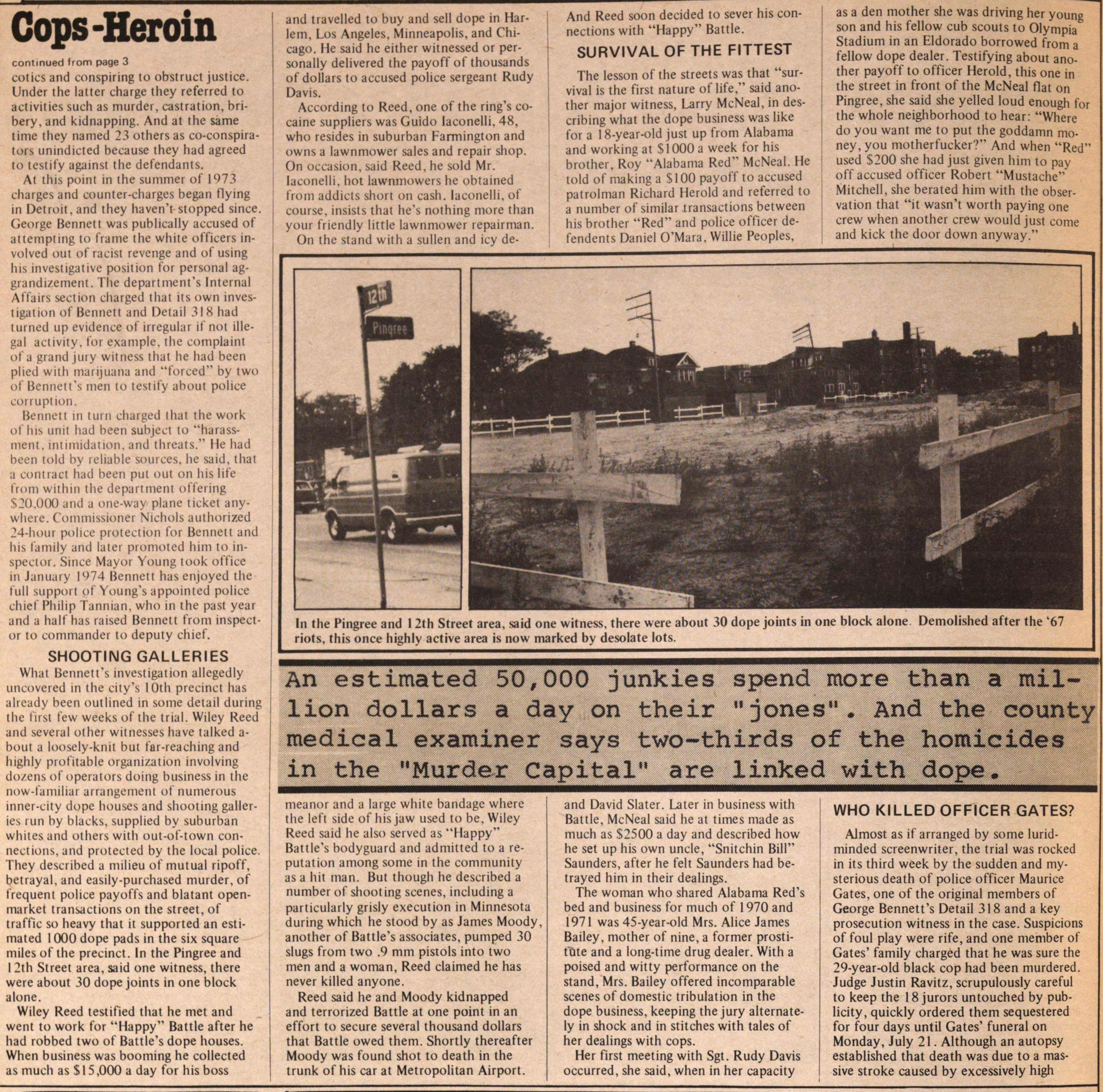

What Bennett's investigation allegedly uncovered in the city's 10th precinct has already been outlined in some detail during the first few weeks of the trial. Wiley Reed and several other witnesses have talked about a loosely-knit but far-reaching and highly profitable organization involving dozens of operators doing business in the now-familiar arrangement of numerous inner-city dope houses and shooting galleries run by blacks, supplied by suburban whites and others with out-of-town connections, and protected by the local police. They described a milieu of mutual ripoff, betrayal, and easily-purchased murder, of frequent police payoffs and blatant open market transactions on the street, of traffic so heavy that it supported an estimated 1000 dope pads in the six square miles of the precinct. In the Pingree and 12th Street area, said one witness, there were about 30 dope joints in one block alone.

Wiley Reed testified that he met and went to work for "Happy" Battle after he had robbed two of Battle's dope houses. When business was booming he collected as much as $ 15,000 a day for his boss and travelled to buy and sell dope in Harlem, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, and Chicago. He said he either witnessed or personally delivered the payoff of thousands of dollars to accused police sergeant Rudy Davis.

According to Reed, one of the ring's cocaine suppliers was Guido Iaconelli, 48, who resides in suburban Farmington and owns a lawnmower sales and repair shop. On occasion, said Reed, he sold Mr. Iaconelli, hot lawnmowers he obtained from addicts short on cash. Iaconelli, of course, insists that he's nothing more than your friendly little lawnmower repairman.

On the stand with a sullen and icy demeanor and a large white bandage where the left side of his jaw used to be. Wiley Reed said he also served as "Happy" Battle's bodyguard and admitted to a reputation among some in the community as a hit man. But though he described a number of shooting scenes, including a particularly grisly execution in Minnesota during which he stood by as James Moody, another of Battle's associates, pumped 30 slugs from two .9 mm pistols into two men and a woman, Reed claimed he has never killed anyone.

Reed said he and Moody kidnapped and terrorized Battle at one point in an effort to secure several thousand dollars that Battle owed them. Shortly thereafter Moody was found shot to death in the trunk of his car at Metropolitan Airport. And Reed soon decided to sever his connections with "Happy" Battle.

SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST

The lesson of the streets was that "survival is the first nature of life," said another major witness, Larry McNeal, in describing what the dope business was like for a 18-year-old just up from Alabama and working at $1000 a week for his brother, Roy "Alabama Red" McNeal. He told of making a $100 payoff to accused patrolman Richard Herold and referred to a number of similar transactions between his brother "Red" and police officer defendents Daniel O'Mara, Willie Peoples, and David Slater. Later in business with Battle, McNeal said he at times made as much as $2500 a day and described how he set up his own uncle, "Snitchin Bill" Saunders, after he felt Saunders had betrayed him in their dealings.

The woman who shared Alabama Red's bed and business for much of 1970 and 1971 was 45-year-old Mrs. Alice James Bailey, mother of nine, a former prostitute and a long-time drug dealer. With a poised and witty performance on the stand, Mrs. Bailey offered incomparable scenes of domestic tribulation in the dope business, keeping the jury alternately in shock and in stitches with tales of her dealings with cops.

Her first meeting with Sgt. Rudy Davis occurred, she said, when in her capacity as a den mother she was driving her young son and his fellow cub scouts to Olympia Stadium in an Eldorado borrowed from a fellow dope dealer. Testifying about another payoff to officer Herold, this one in the street in front of the McNeal flat on Pingree, she said she yelled loud enough for the whole neighborhood to hear: "Where do you want me to put the goddamn money, you motherfucker?" And when "Red" used $200 she had just given him to pay off accused officer Robert "Mustache" Mitchell, she berated him with the observation that "it wasn't worth paying one crew when another crew would just come and kick the door down anyway."

WHO KILLED OFFICER GATES?

Almost as if arranged by some lurid-minded screenwriter, the trial was rocked in its third week by the sudden and mysterious death of police officer Maurice Gates, one of the original members of George Bennett's Detail 318 and a key prosecution witness in the case. Suspicions of foul play were rife, and one member of Gates' family charged that he was sure the 29-year-old black cop had been murdered. Judge Justin Ravitz, scrupulously careful to keep the 18 jurors untouched by publicity, quickly ordered them sequestered for four days until Gates' funeral on Monday, July 21. Although an autopsy established that death was due to a massive stroke caused by excessively high blood pressure, suspicions of murderous involvement by fellow cops or underworld types were not likely to be erased or confirmed until completion of a toxicological report.

Gates, described as an intensely dedicated young cop, had been assigned to assist in guarding another prosecution witness, 28year-old Harold Chapman, on the night Gates died. Two days earlier Chapman, a former dope dealer, had become a surprise witness at the trial, offering sensational testimony against Sgt. Rudy Davis.

Originally, defense attorneys had hoped to use Chapman in their continuing effort to attack George Bennett's integrity and methods, since Chapman had earlier charged that two of Bennett's men (one being Gates) had taken him at gun point to the grand jury and had offered him pot. On the stand, however, Chapman testified that he and Rudy Davis had fabricated this story in an effort to cover the fact that Davis had been Chapman's supplier of heroin and cocaine, at times dealing right out of the property room of the 10th precinct station house.

The trial's central question at this point is whether the testimony offered by witnesses with such lurid and often disreputable histories will finally prove firm enough to produce convictions. Defense attorneys have regularly mounted scathing attacks on the credibility of witnesses such as Wiley Reed and Alice James Bailey, pounding away at every inconsistency with prior testimony and emphasizing that many who have so far taken the stand have been promised freedom from prosecution and given substantial renumeration in exchange for their testimony. Wiley Reed, for example, has received more than $19,000 while in protective custody over the past two years.

Those charged with the responsibility of judging witness credibility are, of course, the 18 jurors selected to sit on the case. Painstakingly chosen from a panel of more than 700 prospective jurors, the five whites and thirteen blacks seem a fair cross-section of the defendants' peers in terms of age and background. The enlarged jury (18 instead of the usual 14) was deemed necessary because the trial is expected to last from four to six months. When the time for deliberation does arrive, lots will be drawn to determine the twelve who will render the final verdicts.

When those verdicts come, it could signal the ending of decades of police omnipotence in the affairs of the city, due to the efforts of an investigative journalist, the newly formed police Internal Affairs Section (largely the creation of the new city administration), and marxist judge Justin Ravitz. Several years ago, a trial of police of this magnitude would never have been allowed by the powers that be, who were clearly lined up on the side of the police. With the Pringree Street trial, their grip on the city may be finally fading.

Article

Subjects

Freeing John Sinclair

Old News

Ann Arbor Sun