10 Precinct Conspiracy Trial "Happy" Battle Sings For His Life

By Pamela Johnson

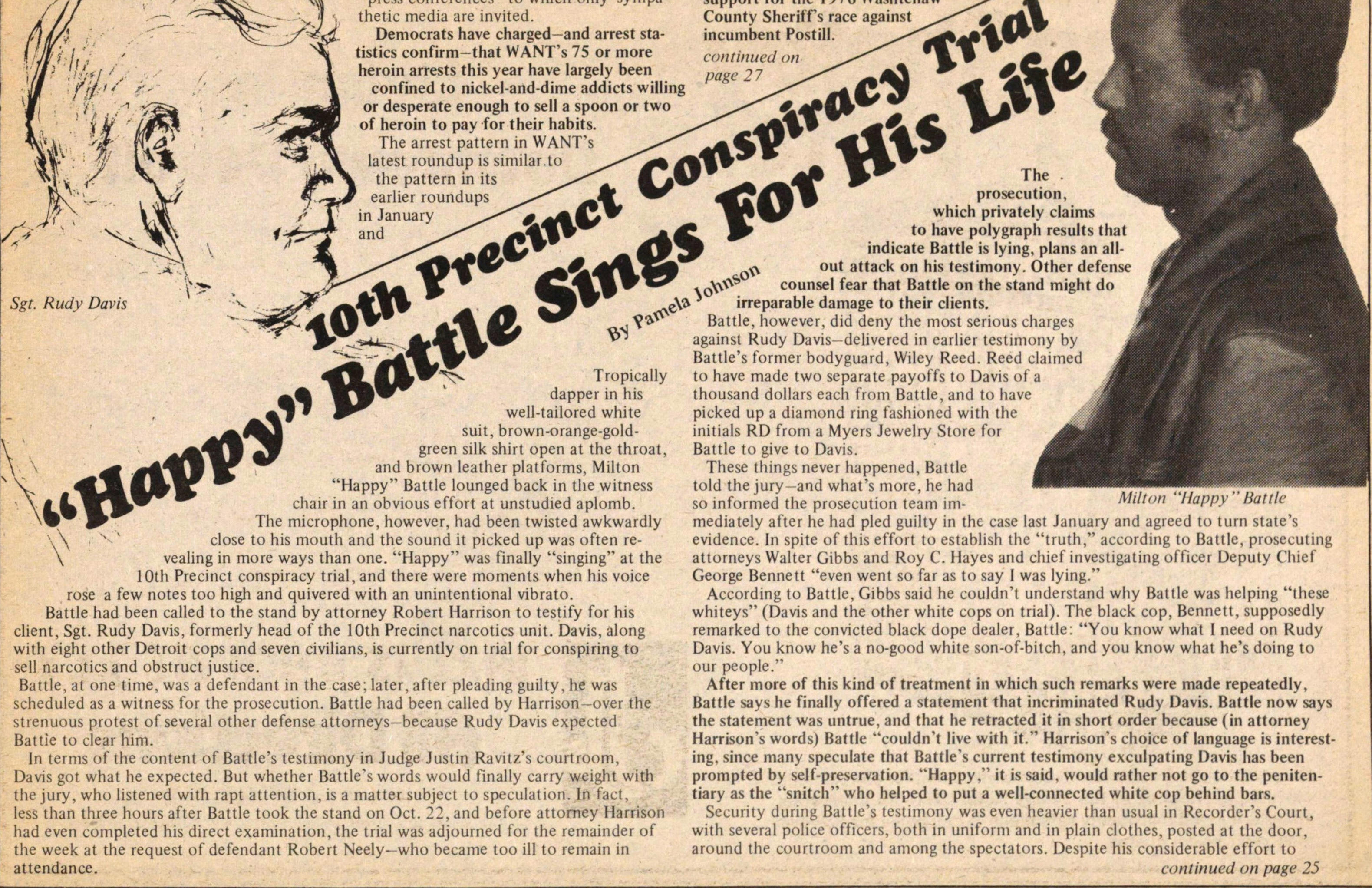

Tropically dapper in his well-tailored white suit brown-orange-gold-green silk shirt open at the throat, and brown leather platforms, Milton "Happy" Battle lounged back in the witness chair in an obvious effort at unstudied aplomb. The microphone, however, had been twisted awkwardly close to his mouth and the sound it picked up was often revealing in more ways than one. "Happy" was finally "singing" at the 10th Precinct conspiracy trial, and there were moments when his voice rose a few notes too high and quivered with unintentional vibrato.

Battle had been called to the stand by attorney Robert Harrison to testify for his client, Sgt. Rudy Davis, formerly head of the 10th Precinct narcotics unit. Davis, along with eight other Detroit cops and seven civilians, is currently on trial for conspiring to sell narcotics and obstruct justice.

In terms of the content of Battle's testimony in Judge Justin Ravitz's courtroom, Davis got what he expected. But whether Battle's words would finally carry weight with the jury, who listened with rapt attention, is a matter subject to speculation. In fact, less than three hours after Battle took the stand on Oct. 22,, and before attorney Harrison had even completed his direct examination, the trial was adjourned for the remainder of the week at the request of defendant Robert Neely -- who became too ill to remain in attendance.

The prosecution, which privately claims to have polygraph test results that indicate Battle is lying, plans an all-out attack on his testimony. Other defense counsels fear that Battle on the stand might do irreparable damage to their clients.

Battle, however, did deny the most serious charges against Rudy Davis -- delivered in an earlier testimony by Battle's former bodyguard, Wiley Reed. Reed claimed to have made two separate payoffs to Davis of a thousand dollars each from Battle, and to have picked up a diamond ring fashioned with the initials RD from a Myers Jewelry Store for Battle to give to Davis.

These things never happened, Battle told the jury -- and what' smore, he had so informed the prosecution team immediately after he had pled guilty in the case last January and agreed to turn state's evidence. In spite of this effort to establish the "truth," according to Battle, prosecuting attorneys Walter Gibbs and Roy C. Hayes and chief investigating officer Deputy Chief George Bennett "even went so far as to say I was lying."

According to Battle, Gibbs said he couldn't understand why Battle was helping "these whiteys." (Davis and the other white cops on trial). The black cop, Bennett, supposedly remarked to the convicted black dope dealer, Battle: "You know what I need on Rudy Davis. You know he's a no-good white son-of-a-bitch, and you know what he's doing to our people."

After more of this kind of treatment in which such remarks were made repeatedly, Battle says he finally offered a statement that incriminated Rudy Davis. Battle now says the statement was untrue, and that he retracted it in short order because (in attorney Harrison's words) Battle "couldn't live with it." Harrison's choice of language is interesting since many speculate that Battle's current testimony exculpating Davis has been prompted by self-preservation. "Happy," it is said, would rather not to go the penitentiary as the "snitch" who helped put a well-connected white cop behind bars.

Security during Battle's testimony was even heavier than usual in Recorder's Court, with several police officers, both in uniform and plainclothes, posted at the door, around the courtroom, and among the spectators. Despite his considerable effort to appear calm on the stand, Battle's frequent requests for conferences with his attorney, his smiles and chuckles at seemingly inappropriate moments, and the tremulous waver in his voice whenever he was required to speak more than a few words at a time, all hinted at considerable stress and tension in the man they used to call "Happy" down on Twelfth and Pingree.

It seems likely that in listening to Battle, more than one juror was reminded of earlier testimony from three or four members of the McNeal clan, who served as major prosecution witnesses. They said Happy had "screamed and cried like a woman" when he was beaten up, robbed, and extorted on a number of occasions by patrolmen/defendants David Slater and Willie Peeples. Slater and Peeples watched quietly from their corner of the courtroom, no doubt waiting to see what Mr. Battle might have to say about those alleged pleasantries.

That question, and many others, were left-hanging when court was adjourned and Battle was escorted back to his current resident in the Wayne County Jail.

How effective would the prosecution be in cross-examining Battle and in bringing on rebuttal witnesses? Prosecutor Gibbs frankly admitted that Battle had damaged the People's case, both by denying his earlier charges and by attacking the integrity and methods of the prosecution team. Deputy Chief Bennett has repeatedly denied all accusations of misconduct, and will probably be called as a rebuttal witness to do so again in more specific terms.

Does the prosecution, in fact, have lie-detector results showing that Battle is prevaricating about his real connection with Rudy Davis? If such results do exist, can they be made known in some fashion to the jury?

Finally, would Rudy Davis finally take the stand in his own defense?

Preliminary reports indicated that he would. But last year, during the Recorder's Court trial in which Davis was convicted of conspiring to obstruct justice and take bribes, similar reports proved to be unfounded. In that case -- which got him three to five years, and is now on appeal -- Davis decided not to take the stand, and it was rumored that his motive was at least in part that he did not wish to be questioned about his financial situation.

As a sergeant in the early '70s, Davis's basic salary would have been in the $16,000 range. One source close to the prosecution says it has records indicating Rudy was banking considerably more than might seem reasonable on such an income and describes the probable effect of such evidence as "devastating."

In the meantime, Happy Battle will be called back to the mic to finish his song. And all sixteen defendants, as well as the seventeen jurors charged with judging witness credibility, will be hanging on every word.

Article

Subjects

Freeing John Sinclair

Old News

Ann Arbor Sun