Part 1: From Black Bottom To Mayor Of Detroit Exclusive Interview: Coleman Young

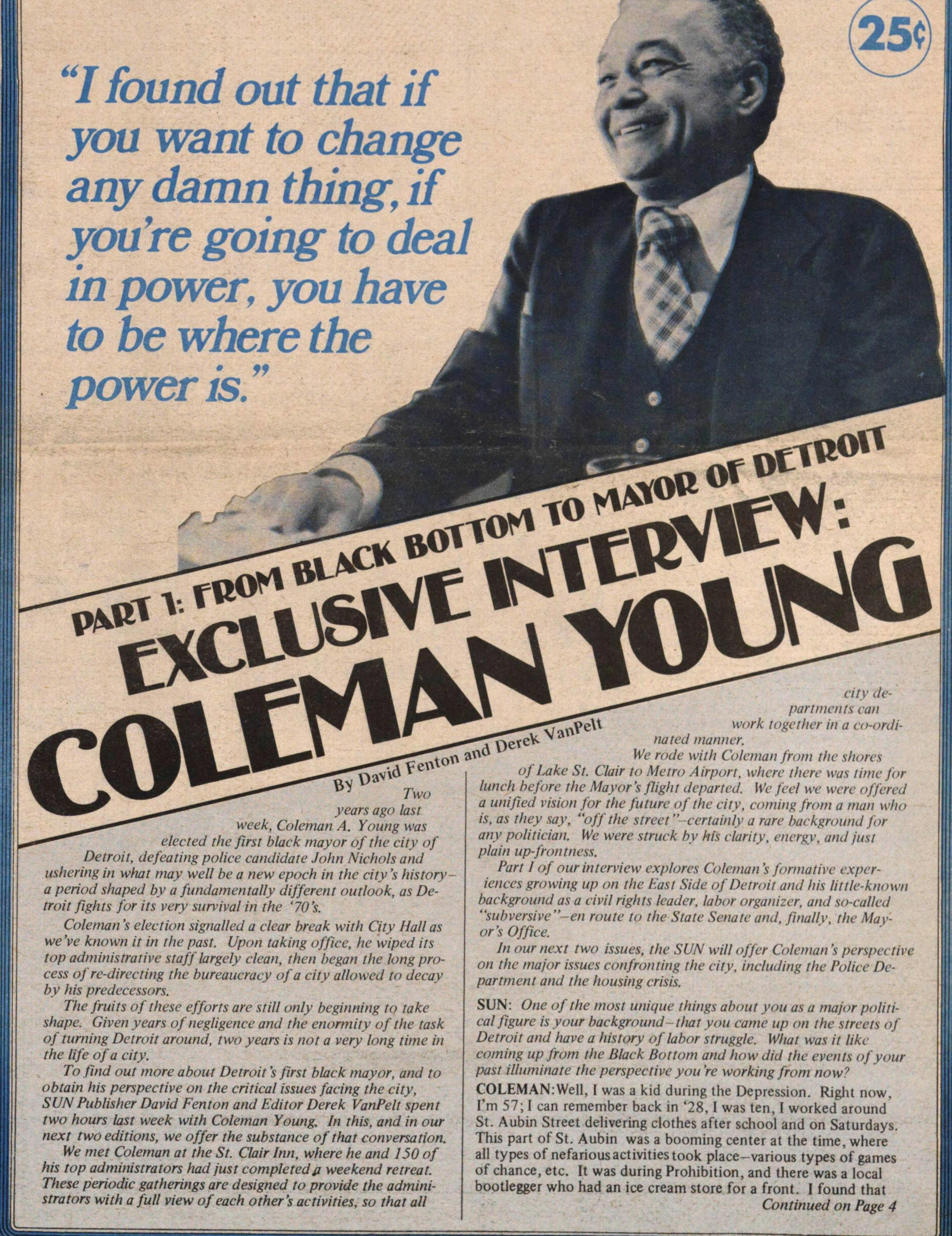

"I found out that if you want to change any damn thing, if you're going to deal in power, you have to be where the power is."

Part 1: From Black Bottom to Mayor of Detroit

Exclusive Interview: Coleman Young

By David Fenton and Derek VanPelt

Two years ago last week, Coleman A. Young was elected the first black mayor of the city of Detroit, defeating police candidate John Nichols and ushering in what may well be a new epoch in the city's history - a period shaped by a fundamentally different outlook, as Detroit fights for its very survival in the 70s.

Coleman's election signaled a clear break with City Hall as we've known it in the past. Upon taking office, he wiped its top administrative staff largely clean, then began the long process of re-directing the bureaucracy of a city allowed to decay by his predecessors.

The fruits of these efforts are still only beginning to take shape. Given years of negligence and the enormity of the task of turning Detroit around, two years is not a very long time in the life of a city.

To find out more about Detroit's first black mayor, and to obtain his perspective on the critical issues facing the city, SUN Publisher, David Fenton and Editor, Derek VanPelt spent two hours last week with Coleman Young. In this, and in our next two editions, we offer the substance of that conversation.

We met Coleman at the St. Clair Inn, where he and 150 of his top administrator had just completed a weekend retreat. These periodic gatherings are designed to provide the administrator with a full view of each other's activities, so that all city departments can work together in a coordinated manner.

We rode with Coleman from the shores of Lake St. Clair to Metro Airport, where there was time for lunch before the Mayor's flight departed. We feel we were offered a unified vision for the future of the city, coming from a man who is as they say, "off the street" - certainly a rare background for any politician. We were struck by his clarity, energy, and just plain up-frontness.

Part 1 of our interview explores Coleman's formative experiences growing up on the East Side of Detroit and his little-known background as a civil rights leader, labor organizer, and so-called "subversive" - en route to the State Senate and, finally, the Mayor's Office.

In our next two issues, the SUN will offer Coleman's perspective on the mayor issues confronting the city, including the Police Department and the housing crisis.

Sun: One of the most unique things about you as a major political figure is your background - that you came up on the streets of Detroit and have a history of labor struggle. What was it like coming up from the Black Bottom and how did the events of your past illuminate the perspective you're working from right now?

Coleman: Well, I was a kid during the Depression. Right now, I'm 57; I can remember back in '28, I was ten, I worked around St. Aubin Street delivering clothes after school and on Saturdays. This part of St. Aubin was a booming center at the time, where all types of nefarious activities took place - various types of games of change, etc. It was during Prohibition, and there was a local bootlegger who had an ice cream store for a front. I found that [continued on page 4]

[continued from the cover] very educational. There were all kinds of churches and social organizations around there, entertainment spots, and people knew each other. My grandparents lived in the neighborhood. We came up from the south around '22. My grandfather came up frist, found a job, then sent for my grandmother, then my aunts and uncles, then my father came up until he could send for us. That was the pattern in those days. This was an exciting period for us. The community was basically Italian. It had previously been German. There were a number of Jewish people there, too. In fact the old Hastings Street area was primarily Jewish. Practically every black church in the damn city, for that matter, was a former Jewish synagogue, because black expansion generally follows Jewish flight. There was also a few Greeks in the lower section.

So in the early days, I was exposed to all these cultures, and could appreciate them. Together, they cemented a real community. There were no locked doors, but it was rough. There'd be a fight every damn day. Maybe it was the Greeks and Italians against the Blacks and the Irish one day; then the next day, you'd fight by streets - with everybody on the street, no matter what. The fighting was the thing. This was the kind of neighborhood in which I grew up.

There was a barbershop there which a bunch of UAW organizers used to come to. This was in the 30s, while I was in high school. I'd sit around and listen to theses guys argue union politics - all kinds of social ideologies, you know. I knew them all - Marxists, Troyskyites, the Social Democrats.

This was during a period of people being thrown out of their homes and the workers moving them back in. I've seen groups of workers invade welfare stations and pass out shoes and clothing where there was too much red tape. There were soup kitchens around - a lot of turmoil and excitement, which I got caught up in. My education started with the barbershop discussions, which I soon grew to participate in.

They were hard times, but I think it was different in the '30's. There was not the ready contrast between affluence and poverty. Now I'm sure there was affluence there, but we didn't have the same communications. There was no television. We didn't have an automobile to get to Grosse Pointe or Palmer Park. The only exposure we got was from double feature movies, the big films of '34 and '35. The glittering wealth, opulence, food, made for very mixed emotions. Now today's young people know better.

That period produced a feeling of togetherness. When the bulldozers came to tear up the community for high ways, those who could afford to, relocated outside the old area. For a long time, people would come back down on the weekends, get their hair cut, drink whiskey, play poker, or something like that. There was a certain democratic leavening experience of a community, like a small town. People weren't as scattered and rootless. We had doctors, lawyers, Ph.D.'s, judges, and also guys that just got out of Jackson [Prison], or worked on the line at Ford's. In a sense there was no difference. More than anything else, I keep pounding at that, it was criminal to fractionalize, to raze cohesive communities, where there was social interaction which provided for a certain stability, lack of crime, etc. The bulldozers just rolled through.

Sun: So that was the neighborhood. How did you get involved as a labor organizer?

Coleman: I had taken a college prep course at Eastern High School, where I was entitled to a scholarship to U of M, but got screwed out of it for being black, even though i was number two in the class. So I entered an apprenticeship program for skilled trades at Ford's as an electrician. There were only two of us. I came out of the course with 100 on all the goddamn tests. The other guy was white, with a 68 average, but his father happened to be a foreman, there was one job to be had, and I don't have to tell you any more.

So I found myself in the motor building and became active in the union movement, which at that time was underground at Ford's. Harry Bennett recruited ex-thugs, fighters, murderers, etc., as servicemen at the plants. They were dressed plain like workers. It's hard to believe now the way that plant was - you couldn't smoke, they had wide open toilets with no doors. And a serviceman regularly patrolled the johns to determine how long you'd been there. The pace was so goddamn killing, you had to get some rest, and the only way you could was to sit down for a couple minutes in the john. I've seen men take a newspaper in front of their face and actually get a five minute nap, but they would tap their foot while they were sleeping. When you got caught, it was your job - no grievance, not even a shower.

I wasn't as cool as some of the old timers, talked a little too much to the wrong people - the agents didn't wear pins so you couldn't see who they were. When my activities in the union became known the the company, they put a big goon on me, on the machine right across from me on the assembly line. He called me a black son of a bitch, or a nigger, some name to provoke a fight, and he started to cross the conveyor line between us. I hadn't been raised in the ghetto for nothing. I had a steel bar maybe a inch in diameter used to unjam the machinery, and just laid it across his head. He fell into the conveyor full of sharp metal shavings and got dumped into a bucket car.

Sun: Sounds like that was it for you...

Coleman: They fired me for fighting, and from that point on I became a union organizer. I worked for a couple civil rights organizations, causes, and then went to the post office where I worked for five months and 29 days. Probation, of course, was six months. They fired me on the very last day. See, I was the editor for the union newspaper and made the mistake of calling this supervisor a Hitler. That of course was my ass - I should never have put that in print.

Before the post office, I'd been involved in the Rouge plant strike in May of '41, and when I came out of the post office I joined a civil rights coalition. There was a black housing project called Sojourner Truth in the northern party of the city, during World War II. Conservative forces were opposing having blacks move into that area of the city, there was a lynch atmosphere. We eventually won that fight, where probably for the first time in the civil rights movement we introduced the union tactic of mass protest and picketing. We had respectable black leadership, like doctors and preachers in particular, using union tactics that were looked down upon as hooligan tactics. And sometime they were. Sometimes your picket sign might be a little bigger than was required to hold up a piece of paper. This strike ushered in a new militancy, the recognition that you had to do more than kiss-ass and negotiate behind closed doors.

Then I was drafted into the Army, where we forced open the Officer's Club for blacks and were arrested in the process. Coming out, the post office union I helped organize - public workers - put me on the payroll as an international rep. So I proceeded to help organize Detroit city employees - the same guys who are giving me trouble now [laughter]

In 1947 I was elected Director of Organization of the Wayne County C.I.O., at the time the highest elected job of any black labor figure. The whole concept of a black caucus emerged there. IN '48 I split with the union and the Democratic Party because I went for Henry Wallace's third party. I don't regret it, either. Going for a third party wasn't easy in those days. Wallace was the first candidate in history of the nation who went into the deep south, together with Paul Robeson, and defied the Jim Crow segregation laws. Now that was something in 1948. Wallace being out there revolutionized American politics. We actually put some much pressure on Harry Truman he stole our program.

But nevertheless I was pretty a hungry guy after losing the election at the CIO due to supporting Wallace, and so for a brief period went back to my original skill, learned from my father - cleaning, spotting, etc. In 1951 I helped found the National Negro Labor Council, an association of black caucuses in the union movement across the country. We had two thrusts - to fight for the promotion of black leadership with the unions, and to fight against job discrimination against blacks. We were pretty effective in both instances. We eventually cracked the UAW; on the economic front we forced Seas Roebuck to hire backs for jobs beyond janitor. Today that might now seem like much, but I can assure you, in '52 this was a breakthrough.

Sun Most younger people don't have much sense of what it was like back then.

[continued on page 23]

Coleman: We were picketing, believe it or not, for the right to be served in downtown Detroit, and even on 12th Street. That's how recent this change has been. So naturally, anybody such as the National Negro Labor Council, by definition of our activities, picketing and demanding - was subversive. That's what they called me before the House Un-American Activities Committee, in February of 1952.

It was during the height of McCarthy, when they were going into towns and literally terrorizing people. The mere mention of somebody's name by some damn stool pigeon was enough to get them fired, and in some cases harmed bodily. I've forgotten the name of the chairman of the damn thing, he was from Alabama. Well, we did a little research on him and found out that about 85% of his district was black, but lack people weren't allowed to vote. So he must have been elected by less than 20% of the electorate. And he's gonna lecture me about "un-American activities." I said, "I ain't gonna take this shit." So we did not.

I think you should record that Detroit was the first city where the Un-American Activities Committee ran into real opposition. That was the beginning of the end. I used the Fifth Amendment, the Fist Amendment, but always as part of an attack. The tactic began to spread, and people stopped taking their crap, because these guys, they were defenseless in terms of their own credentials when they start talking about "Americanism".

Sun: How did you recover from that period to go on and run for State office?

Coleman: Well in the black community and the liberal white community, telling off these southern crackers made me something of a hero. I was approached by a group of black Democratic leaders who wanted me to run of State Senate as a Democrat. I was convinces at the time, and the fellows that I was working with - guys and gals, I might say, because even then we were relatively advanced on the question of women's rights - we had in our leadership outstanding women trade unionists. At any rate, we felt that we had a movement that would be effective, that I was more valuable in the NNLC than lost in what we looked upon as a corrupt political process.

Sun: You still might look at it that way.

Coleman: You might, but I found out a little later that if you want to change any goddamn thing, if you're going to deal in power, you have to be where the power is. And we are making some meaningful changes in Detroit against some powerful opposition, a built-in bureaucracy, a powerful Police Department opposition.

But anyway, I decided not to run. Soon after, the National Negro Labor Council became a victim of the Subversive Activities Control Board, which we called SCAB. This was the most intense and arrogant period. We were declared a subversive activity. The reversals of due process and the assumption of innocence until proven guilty - we were guilty until we could prove ourselves innocent. And it cost literally hundreds of thousands of dollars to prove yourself innocent - which we didn't have. So therefore we were guilty, cause we could never prove we were innocent.

Sun: American jurisprudence - "just-us"

Coleman: I remember the convention we had in Detroit in which we made the decision to dissolve the organization. I don't think I had cried since I was a kid. They broke us. What they had done was to get all kinds of B.S. evidence. They said the NNLC was a communist organization and that Coleman Young, who heads the organization, is one of the leading Communists in the U.S. "He takes orders directly from Moscow," and all that is bullshit. Well, somebody in Congress inserted the whole goddamn report into the Congressional records with no proof or anything. Every time I run for office, somebody digs up the records, and there it is, official. We attempted to answer the charges until we found out that there just was no answer. It must have cost of 35 or 40 thousand dollars just to draw a brief to get a hearing. This broke my organization.

Sun: That's why they did it.

Coleman: My staff consisted of four people, our whole national staff. At the 30-odd councils we had across the country, we had maybe fifty full-time people total. But most of us were getting paid every third week. As a result, we did not pay, I did not pay our federal income tax deduction. Owed about three or four thousand bucks. You know, you look at stories about the government just for wiping out, forgiving corporations for 10, 12 million dollars that they owed, but they made us, I should say me, pay every pretty penny.

In dissolving the organization, I burned the records of our 50,000 members, because it was very obvious that if those lists ever got in the wrong hands, there'd be a blacklist and wholesale firings. I personally assumed the four or five thousand we owed the feds. Now that was a lot of damned money in 1954, when we dissolved, especially since I myself was on the blacklist and couldn't find a job.

I went back to Ford's, where I had helped organize the union. The probation was 90 days. I worked 89 - they fired me on the 90th day. By this time, I was on the teletype. I went out to Dodge Main in Hamtramck and was hired. They put all backs in the foundry back then. The first day, a super intendent sees me and ordered me removed. So I took a small job at a luggage plane on Ecorse, where a guy was something of a progressive. But later on, even he had to lay me off.

So then I worked odd jobs between '55 and 1960, when I re-entered politics by running as a delegate to the state constitutional convention. I was elected and served in 1961, then ran for State Rep in '62, missing by about seven votes. I worked from '62 to '64 in the credit union movement, selling insurance, 'till elected to the State Senate in 1964.

-------------------------------

While in the State Senate, Coleman Young fought discrimination against blacks in the Police Department of Detroit and the State Police; authored the Detroit school decentralization bill; and pushed for low-income housing and a steeply graduated state income tax, instead of the present flat rate arrangement. He was the key strategist in passing the state's Open Housing Law, and worked every year in legislative session for drastic reform of the state's marijuana laws; abortion reform; police review boards; and consumer protection legislation.

From the State Senate, Coleman A. Young went on to run for and win the office of Mayor of Detroit two years ago last week.

In our next issue, out November 26, Part 2 of our exclusive interview with the Mayor will focus on his heated struggle with the Detroit Police Officer's Association and his efforts to reverse the deterioration of Detroit's housing and neighborhoods, including his approach to the problem of HUD-owned abandoned housing.