The Motor City Bombers Off The Streets And Olympic Bound

By Joel Greer

Photos by Joel Unangst

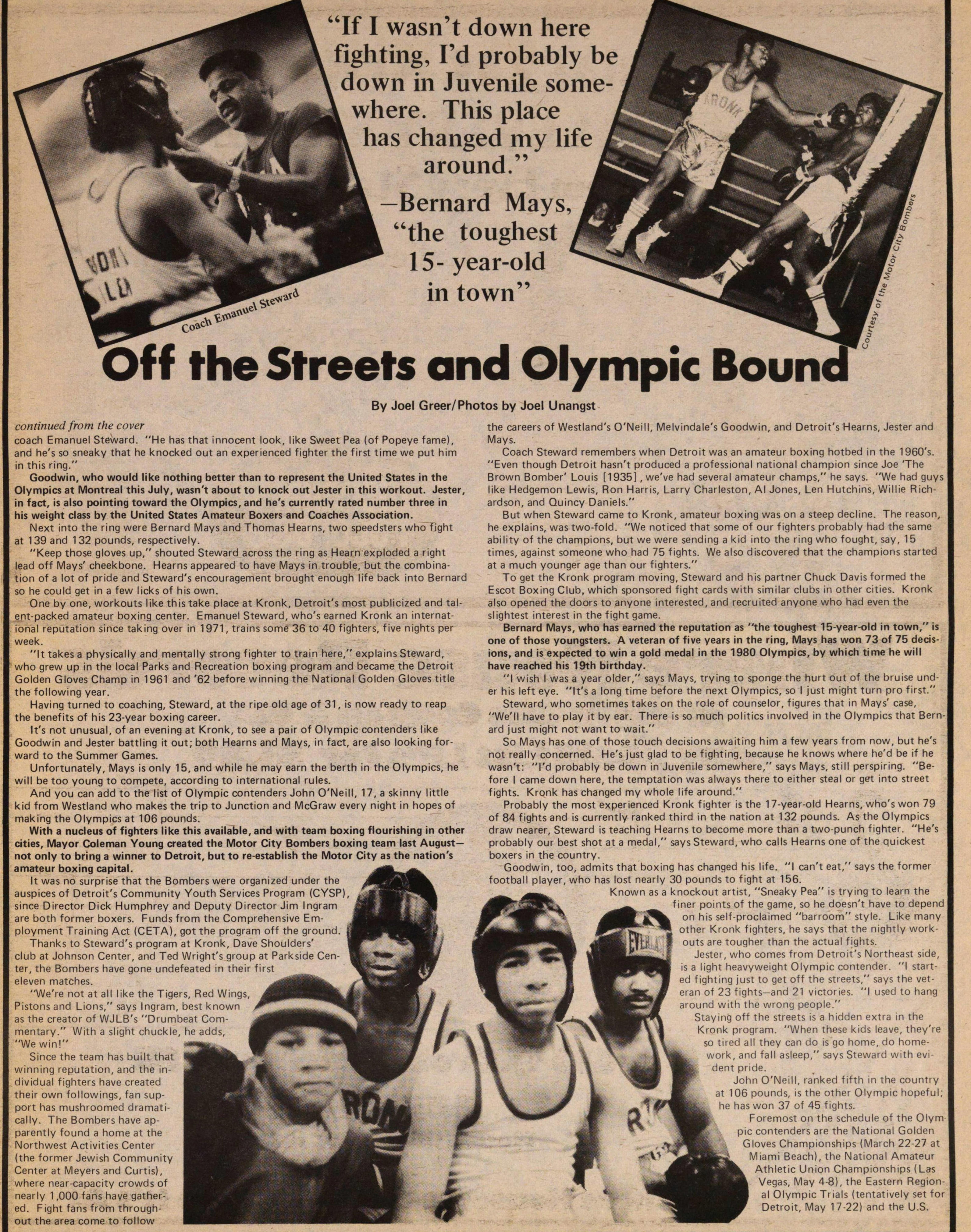

Down a flight of stairs at the Kronk Recreation Center boxing gym, the evening's action is already heating up. Mickey Goodwin, 18, a 156-pound white kid from Melvindale, is battling Rick Jester, a 178-pound black kid who is at least four inches taller. It looks almost like David meeting Goliath, until you notice Goodwin is standing right in there, scoring with his left jab, connecting with his right uppercut, and bouncing the 19-year-old Jester off the ropes with a powerful left hook.

As if this wasn't enough, our escort assures us that Goodwin is no patsy, for in his eleven months of amateur boxing, he has won 23 of 24 fights, with 21 of them coming by knockout.

"That's why we call him 'Sneaky Pea,'" says Kronk boxing coach Emanual Steward. "He has that innocent look, like Sweet Pea (of Popeye fame), and he's so sneaky that he knocked out an experienced fighter the first time we put him in the ring."

Goodwin, who would like nothing better than to represent the United States in the Olympics at Montreal this year, wasn't about to knock Jester in this workout. Jester, in fact, is also pointing toward the Olympics, and he's currently rated number three in his weight class by the United States Amateur Boxers and Coaches Association.

Next into the ring were Bernard Mays and Thomas Hearns, two speedsters who fight at 139 and 132 pounds, respectively.

"Keep those gloves us," shouted Steward across the ring as Hearn exploded a right lead off Mays' cheekbone. Hearns appeared to have Mays in trouble, but the combination of a lot of pride and Steward's encouragement brought enough life back in Bernard so he could get in a few licks of his own.

One by one, workouts like this take place at Kronk, Detroit's most publicized and talent-packed amateur boxing center. Emanuel Steward, who's earned Kronk an international reputation since taking over in 1971, trains some 36 to 40 fighters, five nights per week.

"It takes a physically and mentally strong fighter to train here," explains Steward, who grew up in the local Parks and Recreation boxing program and became the Detroit Golden Gloves Champ back in 1961 and '62 before winning the National Golden Gloves title the following year.

Having turned to coaching, Steward, at the ripe old age of 31, is now ready to reap the benefits of his 23-year-boxing career.

It's not unusual, of an evening at Kronk, to see a pair of Olympic contenders like Goodwin and Jester battling it out; both Hearns and Mays, in fact, are also looking forward to the Summer Games.

Unfortunately, Mays is only 15, and while he may earn the berth in the Olympics, he will be too young to complete, according to international rules.

And you can add to the list of Olympic contenders John O'Neill, 17, a skinny little kid from Westland who makes the trip to Junction and McGraw every night in hopes of making the Olympics at 106 pounds.

With a nucleus of fighters like this available, and with team boxing flourishing in other cities, Mayor Coleman young created the Motor City bombers boxing team last August -- not only to bring a winner to Detroit, but to re-establish the Motor City as the nation's amateur boxing capital.

It was no surprise that the Bombers were organized under the auspices of Detroit's Community Youth Services Program (CYSP) since Director Dick Humphrey and Deputy Director Jim Ingram are both former boxers. Funds from the Comprehensive Employment Training Act (CETA) got the program off the ground.

Thanks to Steward's program at Kronk, Dave Shoulders' club at Johnson Center and Ted Wright's group at Parkside Center, the Bombers have gone undefeated in their first eleven matches.

"We're not at all like the Tigers, Red Wings, Pistons, and Lions, says Ingram, best known as the creator or WJLB's "Drumbeat Commentary." With a slight chuckle, he adds, "We in!"

Since the team has built that winning reputation, and the individual fighters have created their own followings, fan support has mushroomed dramatically. The Bombers have apparently found a home at the Northwest Activities Center (the former Jewish Community Center at Meyers and Curtis) where near-capacity crowds of nearly 1,000 fans have gathered. Fight fans from throughout the area come to follow the careers of Westland's O'Neill, Melvindale's Goodwin, and Detroit's Hearns, Jester, and Mays.

Coach Steward remembers where Detroit was an amateur boxing hotbed in the 1960s. "Even though Detroit hasn't produced a professional champion since Joe "The Brown Bomber' Louis [1935], we've had several amateur champs," he says. "We had guys like Hedgemon Lewis, Ron Harris, Larry Charleston, Al Jones, Len Hutchins, Willie Richardson, and Quincy Daniels."

But when Steward came to Kronk, amateur boxing was on a steep decline. The reason, he explains, was two-fold. "We noticed that some of our fighters probably had the same ability of the champions, but we were sending a kid into the ring who fought, say, 15 times, against someone who had 75 fights. We also discovered that the champions started at a much younger age than our fighters."

To get the Kronk program moving, Steward and his partner Chuck Davis formed the Escot Boxing Club, which sponsored fight cards with similar clubs in other cities. Kronk also opened the doors to anyone interested and recruited anyone who had even the slightest interest in the fight game.

Bernard Mays, who has earned the reputation as "the toughest 15-year-old in town," is one of those youngsters. A veteran of five years in the ring, Mays has won 73 of 75 decisions and is expected to gold medal in the 1980 Olympics, by which time he will have reached in 19th birthday.

"I wish I was a year older," says Mays, trying to sponge the hurt out of the bruise under his left eye. "It's a long time before the next Olympics, so I just might turn pro first."

Steward, who sometimes takes on the role of counselor, figures that in Mays' case, "We'll have to play it by ear. There is so much politics involved in the Olympics that Bernard just might not want to wait."

So Mays has one of those tough decisions awaiting him a few years from now, but he's not really concerned. He's just glad to be fighting because he knows where he'd be if he wasn't: "I'd probably be down in Juvenile somewhere," says Mays, still perspiring. "Before I came down here, the temptation was always there to either steal or get into street fights. Kronk has changed my whole life around."

Probably the most experienced Kronk fighter is the 17-year-old Hearns, who's won 79 of 84 fights and is currently ranked third in the nation at 132 pounds. As the Olympics draw nearer, Steward is teaching Hearns to become more than a two-punch fighter. "He's probably our best shot at a medal," says Steward, who calls Hearns one of the quickest boxers in the country.

Goodwin, too, admits that boxing has changed his life. "I can't eat," says the former football player, who has lost nearly 30 pounds to fight at 156.

Known as a knockout artist, "Sneaky Pea," is trying to learn the finer points of the game so he doesn't have to depend on his self-proclaimed "barroom" style. Like many other Kronk fighters, he says that the nightly workouts are tougher than the actual fights.

Jester, who comes from Detroit's Northeast side, is a light heavyweight Olympic contender. "I started fighting just to get off the streets," says the veteran of 23 fights -- and 21 victories. "I used to hang around with the wrong people."

Staying off the streets is a hidden extra of the Kronk program. "When these kids leave, they're so tired all they can do is go home, do homework, and fall asleep," says Steward with evident pride.

John O'Neill, ranked fifth in the country at 106 pounds, is the other Olympic hopeful; he has won 37 of 45 fights.

Foremost on the schedule of the Olympic contenders are the National Golden Gloves Championships (March 22-28 at Miami Beach), the National Amateur Athletic Union Championships, (Las Vegas, May 4-8), the Eastern Regional Olympic Trials (tentatively set for Detroit, May 17-22), and the U.S. Olympic Boxing Trials (Cincinnati, June 9-12). The winners of the four regionals, plus four-at-large boxers, will make up the field in Cincinnati, where the Olympic team members are selected at each weight. An alternate will also be chosen in each weight class for the Games, which being in Montreal July 17.

the Motor City Bombers' next home program is scheduled for the Northwest Activities Center February 21. The Bombers will be meeting a team from Akron, Ohio, and the first match begins at 8 p.m.

With the help of the Bombers, Steward's five-year goal of seeing Kronk establish a national reputation has been realized, so he has now formulated a new one. "I would like the manage a professional world champion," says Steward, who will coach Hearns, Goodwin, and Jester next year when the trio turns pro. "My old friend, Sam LaFata, is already setting up the corporation," adds Steward. "We'll train those fighters during the day, so we can keep the Kronk alive at night."

After all, 11-year old Steve McCrory has already won 14 of 19 fights, and he's looking more like Muhammad Ali every day.

Joel Greer, who lives in Detroit, has written about sports for the Michigan Daily and the Ann Arbor News.