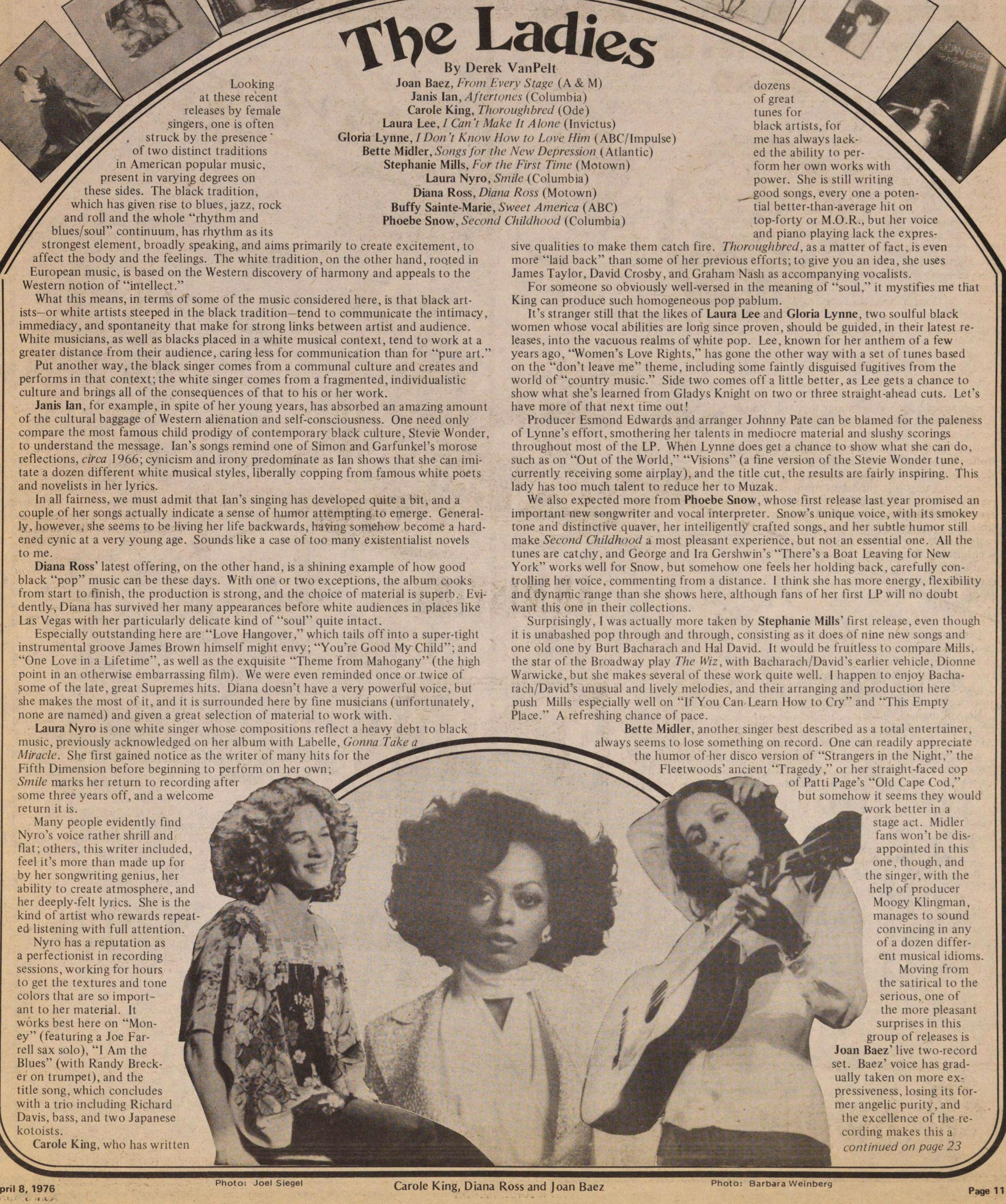

The Ladies

Joan Baez, From Every Stage (A & M)

Janis Ian, Aftertones (Columbia)

Carole King, Thoroughbred (Ode)

Laura Lee, I Can't Make It Alone (Invictus)

Gloria Lynne, I Don't Know How to Love Him (ABC/Impulse)

Bette Midler, Songs for the New Depression (Atlantic)

Stephanie Mills, For the First Time (Motown)

Laura Nyro, Smile (Columbia)

Diana Ross, Diana Ross (Motown)

Buffy Sainte-Marie, Sweet America (ABC)

Phoebe Snow, Second Childhood (Columbia)

Looking at these recent releases by female singers, one is often struck by the presence of two distinct traditions in American popular music, present in varying degrees on these sides. The black tradition, which has given rise to blues, jazz, rock and roll and the whole "rhythm and blues/soul" continuum, has rhythm as its strongest element, broadly speaking, and aims primarily to create excitement, to affect the body and the feelings. The white tradition, on the other hand, rooted in European music, is based on the Western discovery of harmony and appeals to the Western notion of "intellect."

What this means, in terms of some of the music considered here, is that black artists - or white artists steeped in the black tradition - tend to communicate the intimacy, immediacy, and spontaneity that make for strong links between artist and audience. White musicians, as well as blacks placed in a white musical context, tend to work at a greater distance from their audience, caring less for communication than for "pure art." Put another way, the black singer comes from a communal culture and creates and performs in that context; the white singer comes from a fragmented, individualistic culture and brings all of the consequences of that to his or her work.

Janis Ian, for example, in spite of her young years, has absorbed an amazing amount of the cultural baggage of Western alienation and self-consciousness. One need only compare the most famous child prodigy of contemporary black culture, Stevie Wonder, to understand the message. Ian's songs remind one of Simon and Garfunkel's morose reflections, circa 1966; cynicism and irony predominate as Ian shows that she can imitate a dozen different white musical styles, liberally copping from famous white poets and novelists in her lyrics.

In all fairness, we must admit that Ian's singing has developed quite a bit, and a couple of her songs actually indicate a sense of humor attempting to emerge. Generally, however, she seems to be living her life backwards, having somehow become a hardened cynic at a very young age. Sounds like a case of too many existentialist novels to me.

Diana Ross' latest offering, on the other hand, is a shining example of how good black "pop" music can be these days. With one or two exceptions, the album cooks from start to finish, the production is strong, and the choice of material is superb. Evidently, Diana has survived her many appearances before white audiences in places like Las Vegas with her particularly delicate kind of "soul" quite intact.

Especially outstanding here are "Love Hangover," which tails off into a super-tight instrumental groove James Brown himself might envy; "You're Good My Child"; and "One Love in a Lifetime", as well as the exquisite "Theme from Mahogany" (the high point in an otherwise embarrassing film). We were even reminded once or twice of some of the late, great Supremes hits. Diana doesn't have a very powerful voice, but she makes the most of it, and it is surrounded here by fine musicians (unfortunately, none are named) and given a great selection of material to work with.

Laura Nyro is one white singer whose compositions reflect a heavy debt to black music, previously acknowledged on her album with Labelle, Gonna Take Miracle. She first gained notice as the writer of many hits for the Fifth Dimension before beginning to perform on her own; Smile marks her return to recording after some three years off, and a welcome return it is.

Many people evidently find Nyro's voice rather shrill and flat; others, this writer included, feel it's more than made up for by her songwriting genius, her ability to create atmosphere, and her deeply-felt lyrics. She is the kind of artist who rewards repeated listening with full attention.

Nyro has a reputation as a perfectionist in recording sessions, working for hours to get the textures and tone colors that are so important to her material. It works best here on "Money" (featuring a Joe Farrell sax solo), "I Am the Blues" (with Randy Brecker on trumpet), and the title song, which concludes with a trio including Richard Davis, bass, and two Japanese kotoists.

Carole King, who has written dozens of great tunes for black artists, for me has always lacked the ability to perform her own works with power. She is still writing good songs, every one a potential better-than-average hit on top-forty or M.O.R., but her voice and piano playing lack the expressive qualities to make them catch fire. Thoroughbred, as a matter of fact, is even more "laid back" than some of her previous efforts; to give you an idea, she uses James Taylor, David Crosby, and Graham Nash as accompanying vocalists.

For someone so obviously well-versed in the meaning of "soul," it mystifies me that King can produce such homogeneous pop pablum.

It's stranger still that the likes of Laura Lee and Gloria Lynne, two soulful black women whose vocal abilities are long since proven, should be guided, in their latest releases, into the vacuous realms of white pop. Lee, known for her anthem of a few years ago, "Women's Love Rights," has gone the other way with a set of tunes based on the "don't leave me" theme, including some faintly disguised fugitives from the world of "country music." Side two comes off a little better, as Lee gets a chance to show what she's learned from Gladys Knight on two or three straight-ahead cuts. Let's have more of that next time out!

Producer Esmond Edwards and arranger Johnny Pate can be blamed for the paleness of Lynne's effort, smothering her talents in mediocre material and slushy scorings throughout most of the LP. When Lynne does get a chance to show what she can do, such as on "Out of the World," "Visions" (a fine version of the Stevie Wonder tune, currently receiving some airplay), and the title cut, the results are fairly inspiring. This lady has too much talent to reduce her to Muzak.

We also expected more from Phoebe Snow, whose first release last year promised an important new songwriter and vocal interpreter. Snow's unique voice, with its smokey tone and distinctive quaver, her intelligently crafted songs, and her subtle humor still make Second Childhood a most pleasant experience, but not an essential one. All the tunes are catchy, and George and Ira Gershwin's "There's a Boat Leaving for New York" works well for Snow, but somehow one feels her holding back, carefully controlling her voice, commenting from a distance. I think she has more energy, flexibility and dynamic range than she shows here, although fans of her first LP will no doubt want this one in their collections.

Surprisingly, I was actually more taken by Stephanie Mills' first release, even though it is unabashed pop through and through, consisting as it does of nine new songs and one old one by Burt Bacharach and Hal David. It would be fruitless to compare Mills, the star of the Broadway play The Wiz, with Bacharach/David's earlier vehicle, Dionne Warwicke, but she makes several of these work quite well. I happen to enjoy Bacharach/David's unusual and lively melodies, and their arranging and production here push Mills especially well on "If You Can Learn How to Cry" and "This Empty Place." A refreshing chance of pace.

Bette Midler, another singer best described as a total entertainer, always seems to lose something on record. One can readily appreciate the humor of her disco version of "Strangers in the Night," the Fleetwoods' ancient "Tragedy " or her straight-faced cop of Patti Page's "Old Cape Cod," but somehow it seems they would work better in a stage act. Midler fans won't be disappointed in this one, though, and the singer, with the help of producer Moogy Klingman, manages to sound convincing in any of a dozen different musical idioms.

Moving from the satirical to the serious, one of the more pleasant surprises in this group of releases is Joan Baez' live two-record set. Baez' voice has gradually taken on more expressiveness, losing its former angelic purity, and the excellence of the recording makes this a truly intimate concert experience, allowing Baez' exceptional consciousness, humanity, and commitment to be felt as well as heard. The material, half done solo and half with her band, ranges from her early classics of the "folkie" period to the gripping "Ballad of Sacco and Vanzetti" to a cappella gospel.

Another evolving ex-"'folkie," Native American Buffy Sainte-Marie, owes her current direction more to her record company's decision to try to make her a rock and roll star than to her actual talents. Sainte-Marie can be righteous, lyrical, compelling, and eerie when left to her own devices, but what there is of such interest here is crowded out by clumsy attempts to force a conventional "hit" out of her. At any rate, Buffy's weird voice is an acquired taste.

With the possible exceptions of Laura Nyro, who draws so extensively from black music, and Joan Baez, who has a long-standing political commitment to black people, the recordings by white artists we have considered really do little to excite the sensibilities or advance the development of popular music. This, one suspects, is partially due to economic conditions in the music industry that discourage experimentation, and partly due to the dried-up cultural heritage from which most white artists continue to draw.

The easy access of white music to the record market, coupled with the unwillingness to accept black music on the same terms, also leads many black artists into dull Caucasian territory for the sake of commercial survival. Diana Ross, of course, can now afford to record anything she wants, but few share her privilege. And so it will probably remain, unless those who control the music business realize the full potential of the current renaissance in black music.

Article

Subjects

Freeing John Sinclair

Old News

Ann Arbor Sun