Mission Accomplished: Juigalpa Ties Established

On Monday, Nov. 10th, a delegation of 17 Ann Arbor residents returned from a 10 day visit to Managua and Juigalpa, Nicaragua. Juigalpa is Ann Arbor's newest sister city. They were sent there by the citizens of Ann Arbor through the Central American Sister City Task Force. The delegation was greeted at Metro Airport by a crowd of loved ones, well-wishers, and the local media. AGENDA took the opportunity to place a 3-question survey in the hands of each returning delegation member.

The trip to Juigalpa was the result of Ann Arbor's passage of Proposal A last April, a resolution which both condemns U.S. military intervention in Central America and directs Ann Arbor to establish sister city relations with one or more cities in the region. On Sept. 22, Juigalpa, a regional capital 80 miles southeast of Managua, was chosen by the task force.

Seattle was the first city n the U.S. to pass such a resolution. Ann Arbor was the second. Residents in the city of Ypsilanti hope to have such a resolution on the ballot in their city in February. The resolution was passed in Ann Arbor by 61% of the voters.

The group went to learn but also took gifts and supplies, including $6,000 worth of much needed medical supplies and 700 Art Fair T-Shirts. The delegation included citizens from various backgrounds. Mayor Ed Pierce and State Representative Perry Bullard were among them.

Some activities over the 10 day period were scheduled for the group but they were also able to investigate their own fields of interests as well. Ernestine Rodríguez Spruce, a school nurse, visited health care facilities. Kurt Berggren, the only practicing attorney in the group, was able to observe a portion of the trial of Eugene Hasenfus.

AGENDA SURVEY

1. Why did you go to Juigalpa?

2. What were your preconceived notions (if any) about Nicaragua and how did your perceptions change over the course of your visit?

3. Tell your best "people" story.

Kurt Berggren

1. I wanted to go on this trip because the concepts of friendship and peace and sharing are important to me, and they are particularly so in the context of Nicaragua. I feel special compassion for these people who are being terrorized as a direct result of the policies of my government.

2. While I felt that I knew a considerable amount about Nicaragua based upon reading and having friends who had lived and traveled there, my pre-conceived notions were limited to knowing that the Contras operated like clandestine Hell's Angels and that, because of this and because of the U.S. economic blockade, life was very difficult for the people. Those preconceived notions did not change but were completely reinforced to the point of being understatements.

What really did change was my level of feeling toward the Nicaraguans. The extent of their suffering and the extent to which they cooperatively work toward the common goal of improving life for all Nicaraguans, and particularly the poor, left an overwhelming impression. While the people have great animosity toward Reagan and fully expect a U.S. invasion, this feeling of hostility does not include the North American people. Toward us, there seems to be only friendship, warmth and sincerity. The people make a clear distinction between the North American people and their government. It was hard for me to understand how this distinction continued to be made in the face of an atmosphere of constant tension and terror as a direct result of the Contra activities. It was amazing that all of these people could keep smiling, hugging and surviving while lacking so many of the basic necessities for life such as peace, running water, a sewage system, adequate health services and the like that we take for granted.

3. There are so many truly remarkable "people stories" that it is difficult to focus on just one. The following, however, is important for understanding something about the suffering caused by the Contra terrorism that constitutes the "morally bankrupt campaign of brutality against the people of Nicaragua" that the delegation referred to in our press statement upon arriving back in Michigan.

On Friday, November 7 - the same day that two Contra attacks within 20 miles of Juigalpa caused the deaths of ten innocent civilians - I went by jeep with two other Ann Arborites and Raoul Ruben, the Dutch regional director for the cooperative program, to visit a cattle co-op about 25 miles east of Juigalpa. The nine displaced persons in the co-op had just received their land this past month and were in the process of trying to put all the necessary fencing and a temporary dwelling place for themselves and finding and developing a source of water. They expected to receive the cattle within the next month.

After Raoul apologized for our intrusion, introduced us and secured the consent of our hosts, all of us sat around a fire on the dirt floor in their tiny cinderblock "home," with liberated chickens coming and going amongst us. We talked with them while they prepared their meal of rice and frijoles and while rain soaked down on us through their still inadequate roof. Our new amigos had formerly been members of a co-op about 100 miles to the north that had been burned by the Contras in I984, and five of the co-op members had been killed and four kidnapped at that time. A now 1 9-year-old member of this co-op was one of those kidnapped and he told us his story. He was (cont. on PAGE 4)

"Findings of the first Ann Arbor-Juigalpa Sister City Delegation: Nov. 1-10, 1986"

After spending nine intensive days in Nicaragua, the 17 members of the first Ann Arbor-Juigalpa Sister City Delegation find that the voters of Ann Arbor were wise and correct in passing Proposal A. This proposal opposed United States government intervention in Central America and called for the establishment of person-to-person sister city relationships in the region. We urge the voters of other cities to take similar initiatives.

During our visit, we had open access to the people and government of Nicaragua. We had numerous opportunities to engage in frank, on-the-record discussions with national, regional and local government officials. Individually and as a group we visited their homes, schools, churches, hospitals, businesses, media, farms, cooperatives and opposition political leaders. At no time were our actions subject to any control by the Nicaraguan government. Only at the United States Embassy were we denied permission to use tape recorders, take photographs, or quote the inexperienced junior officer who met with us.

Based on our individual and group experiences, we submit the following five findings, to which the delegation unanimously subscribes:

(1) Juigalpa and Nicaragua suffer from a level of poverty unimaginable to most North Americans. Residents of our sister city have no sewage system, an uncertain water supply, limited hearth-care resources, and an economy that barely meets the basic needs of most citizens. Despite these difficult conditions, our hosts were optimistic, energetic, warm-hearted and willing to share their homes and lives with us.

(2) The people of our sister city suffer unnecessary additional hardships due to the economic embargo placed on their country by our government. This embargo deprives them of their largest export market, and access to imported materials that are desperately needed to develop and maintain the fabric of their society.

(3) In Juigalpa and throughout Nicaragua, people are working together in a remarkable atmosphere of political and religious freedom, given the level of poverty and military emergency present in the country. To us, the country's leadership appears to enjoy broad popular support, and seems to be genuinely dedicated to improving health care, basic education, and adult literacy.

(4) We find no evidence of commitment by the Nicaraguan government to external ideologies or the policies of any foreign government. On the contrary, we find the goals of the Nicaraguan government to be national independence, self-determination, and the application of practical solutions to the country's problems. Like all governments, Nicaragua's has made mistakes, and the officials we met were willing to acknowledge them, while adopting a flexible, pragmatic approach to changing policy direction when appropriate.

(5) Above all else, we find that the Contra war of terrorism, financed by our tax dollars, is a morally bankrupt campaign of brutality against the people of Nicaragua. We witnessed the results of a barbarous Contra attack within 17 miles of Juigalpa, that took the lives of five innocent civilians. Since 1980, 35,000 Nicaraguans have been killed.

We further find that the Contras themselves have little support among the people of Niacaragua. The Contras act on behalf of a wealthy country of 240 million people, attempting to impose t's will upon an impoverished country of three million people, half of whom are under age fifteen. This drains the resources of a poor but proud country by diverting material and thousands of young men and women from productive activities to the war effort.

Our sister city of Juigalpa has many material needs, some of which we hope the generous people of Ann Arbor will assist them in meeting over the coming years. But the most important gift we can bring our sister city is the one that Ann Arbor voters requested last April: an end to United States's government support of a war that is destroying their homeland.

Lise Anderson Rev. Virginia Peacock

Kurt Berggren Dr. Edward Pierce

Perry Bullard Mary Lee Pierce

LeRoy Cappaert Thomas Rieke

Joyce Chesbrough Jim Ringold

James Eckroad Ellen Rusten

Katherine Eckroad Ernestine Rodríguez Spruce

Gregory Fox Alan Wald

Joel Goldberg

Kurt Berggren (cont.)

told by the Contras that he would either have his throat cut or he would fight with the Contras in battles. He chose the latter "option," and he was made to fight in ten battles prior to his escape four months later. His compañero, who sat next to him at our meeting, just recently completed two years of service in the Sandinista army and he had fought numerous battles against the Contras. I shall always remember the two amigos shyly sitting on their hammock, speaking softly, smiling constantly, and telling what their lives had been like.

In their short lives, these people had suffered too much already, but despite this, their optimism, cooperative effort and their hopes and beautiful smiles were ever present. They now had something that they could call their own, some land that they could work cooperatively and which they could use to make their lives better. There was no water supply, but they showed us where they eventually hoped to obtain their water and where they hoped to build houses for the members of their co-op. When we left, they went back to working on the fences. It was obvious that they liked each other and that they made good compañeros for each other, and it was also obvious that they liked us for caring about them.

As we were driving back to Juigalpa through areas where there had previously been Contra attacks, Kristen remarked that we should be afraid driving along this road in a jeep. We weren't - perhaps because we would have felt guilty and selfish being afraid for such a brief moment of exposure when the Nicaraguan friends we had just met had to live with fear and anxiety every day.

Joyce Chesbrough

As a longtime Republican party worker and public school teacher (Humanities and Latin American History, Pioneer H.S.), I wanted to see for myself what the look and sound of Nicaragua was like, what the people ate and how they dressed and how they interacted with each other. As a former City Councilwoman who took part in Sister City visitations to Hikone, Japan and Peterborough, Ontario, and led a delegation in 1983 to Tübingen, FRG, I was eager to see in what new directions this sister-city relationship might develop. People-to-people programs give ordinary citizens a far more genuine opportunity to interact as human beings than do the gyrations of our various governments, and such programs should be nurtured and cherished for their common humanity. I suspected that this new sister city might provide an entirely different set of experiences and challenges from the usual pleasant encounters, and, of course, that turned out to be the case.

I also tried, in preparing myself for the trip, to learn as much of the factual history as I could, and to try to keep an open mind, to go down without having preconceived notions of what I was going to find. Two questions were uppermost in my mind as I left, and I asked them of many people during our travels, and I carne home with them stilt unanswered-which, in itself, became the conclusive answer for me. The questions were-and are: who are the Contras and what is their motivation? and, if the Contras prevail, how do they plan to better the lot of the Nicaraguan people?

A critic might well ask, why don't you pose the same two questions about the Sandinistas? Who are they and what are their motivations; and, since they have prevailed, how are they bettering the lot of the Nicaraguan people? Fair enough. Herewith are some of my observations on the Sandinistas. The FSLN, the political party founded in 1961 which spearheaded the drive to topple Somoza in 1979, controls two-thirds of the seats of the National Assembly and is the ruling force in Nicaraguan life although there are other parties to both the right and the left of the FSLN. The leadership is in the hands of the 9 Commandantes, but most of the offices are in young inexperienced hands because is a very youthful society. Of a total population of 3 million, 1/2 are under the age of 15. The goals of the Sandinistas are endlessly detailed in billboards, on flags and posters, on walls and in newpapers, repetitious exhortations to study, to fight, to build, to survive, to emulate, to remember...Sandino, Fonseca, Ortega.. .the litany of heroes and deeds and dangers goes on and on. To what end? To build a proud awareness of one's country and one's role in that country. To nurture a sense of patriotism and dedication and self-sacrifice amid the obvious hardships of daily life. To untie the bonds of servitude forged during 50 years of the Somozas and to create instead a budding sense of self-confidence and participation in the new society.

Are there mistakes in this Sandinista society? you bet! I heard of one young man, a graduate of the U-M Business School, who was put in charge of all of Nicaragua's foreign trade with Canada, the U.S. and Mexico, well over half of all Nicaragua's exports. He was 23 years old and he lasted almost two years, but it was a heavy burden, indeed, for so young and inexperienced a manager. In one other case, the Sandinistas used half of a year's agricultural budget to build a huge sugar processing mill that would have been cost-effective if the price of sugar on the world market stayed at about 60c a pound. Can you imagine what happened when the world price of sugar dropped to 6c a pound?

One hopeful thing which we heard many times from other Americans who have worked for extended periods of time with the Sandinistas is that they are a pragmatic and flexible group, operating by the seat of their pants rather then by any book, particularly by any Marxist-Leninist book. All over the world, the move is toward privatization, toward encouragement of the entrepreneurial spirit which is a hands-down winner over the Soviet model. Why would an intelligent, intensely patriotic government choose an out-dated, creaky Victorian system which everyone but the Russians is eagerly bailing out of? The answer is, of course, they won't, not willingly, at least, and not unless it is the only way to get the military assistance they must have to fight an ever more powerful Contra enemy.

You ask for a "people" story. Well, I think I'll quote Mrs. Hasenfus in today's paper. She said, as her husband was being sentenced to 30 years, "I have only gratitude and love in my heart for the people of Nicaragua, who have treated me with kindness and courtesy rather than the hostility that circumstances would have warranted." We of the Ann Arbor delegation can only echo that observation for we, too, experienced only the goodwill and friendship of a lovely people who certainly have been given every right to feel otherwise.

As to my two questions about the Contras, who are they and what have they to offer? I hope you'll ask those questions of our leaders, and not be put off by platitudes and fear-mongering. They are legitimate questions and they deserve straight answers. We should not settle for less.

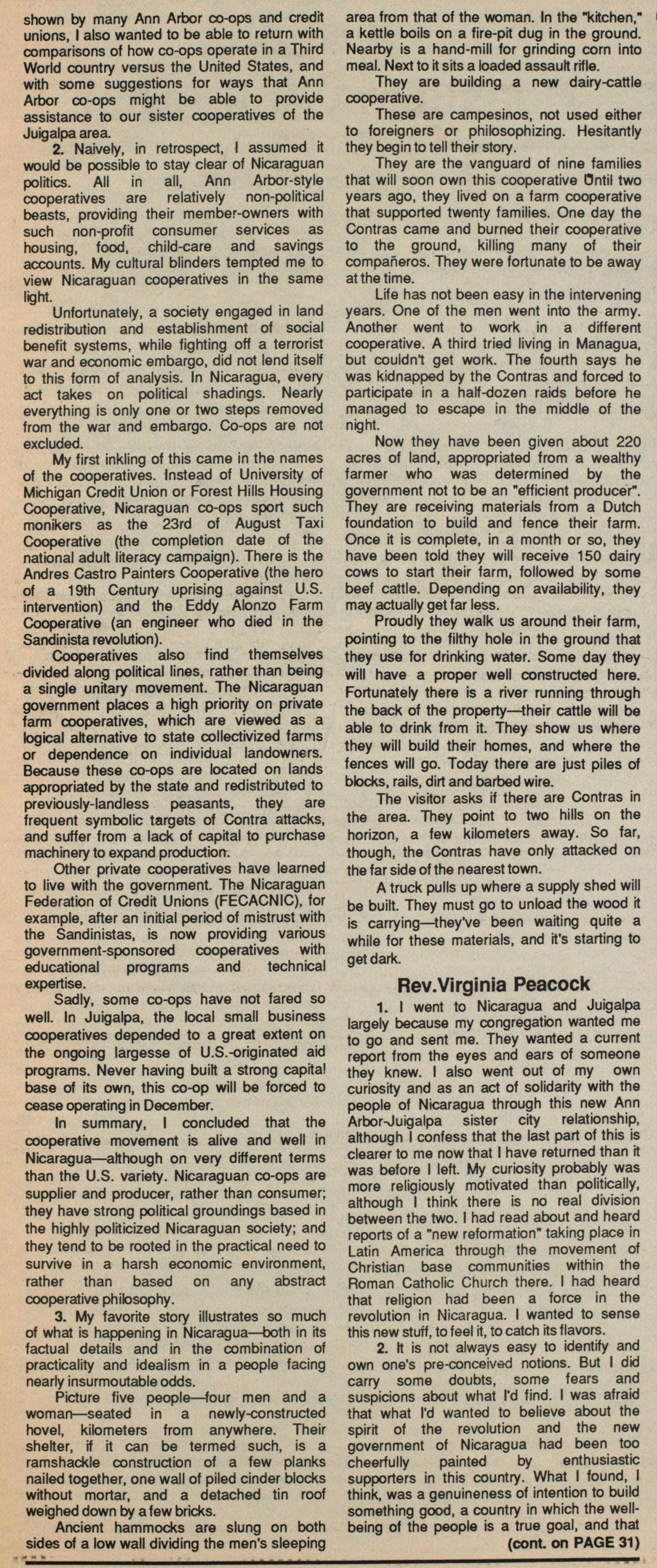

Gregory Fox

The Ann Arbor delegation to Juigalpa marked an important step in the local peace effort that began here in the summer of 1985. We believed that Americans would not tolerate the U.S. sponsored contra aggression if they knew that their taxes were being used to kill Nicaraguan people. I had been involved in each phase of the Initiatives for Peace in Central America, and the trip to Juigalpa was a highly visible manifestation of this community's desire for peace. As a photographer, I felt a need to be along to photodocument this official meeting of Ann Arbor and Juigalpa.

This was not my first trip to Nicaragua: on an earlier trip I had travelled about, getting a "street level" impression. The delegation, by contrast, was structured. We had a full agenda (of our own choosing): meeting with government agencies, with the major opposition party, and with the newspaper, as well as with the pro-contra U.S. embassy. I came away with the impression of a government sincerely working hard for the vast poor of Nicaragua under almost impossible circumstances. They acknowledge that in their short seven years they have made mistakes and fallen short in certain ways. They are also justifiably proud of major achievements: particularly in the areas of health and education, accomplished under conditions of war and an economy of desperation.

The contra terrorists struck while we were in Juigalpa. Just outside of the nearby village of Comalapa, a car carrying farmer-organizer Alfonzo Nunez and six other village residents was ambushed. Several of us from Ann Arbor reached the scene about six hours later. Five people had been killed and two others seriously wounded. The ambushed car was still smoking, but the burnt bodies had been removed to the village. We went to the homes of each of the victims, hoping to show by our presence that we shared in their sorrow. We spoke with a young man who, from a nearby hilltop, had seen the contras put a wounded woman into the burning car.

During this time in Comalapa we were treated with hospitality, despite the relentless slaughter sponsored by our government. The Nicaraguans are able to rise above their grief to distinguish between the actions of the U.S. government and the desires of the U.S. people. It seemed so ironic when the bereaved in Comalapa would thank us for coming to pay our respects. While listening to the cries of a young child of one of the murdered men, I calculated the casualties which would result from a proportional attack on Ann Arbor. We would have lost 252 of our neighbors. This was not an isolated incident. Later that same day the contras attacked a farm co-op killing several farmers. On October 3 there had been a contra attack on a local co-op, and on September 22, the day Juigalpa became our sister city, 4 civilians were murdered by contras.

In the midst of this grief I realized that these people are not losers. They are simply ordinary people doing the extraordinary.

Joel Goldberg

1. Unlike many delegation members, I had not been politically active on Central American issues in Ann Arbor. I joined the delegation to represent Ann Arbor's cooperative businesses and credit unions, to learn about the role co-ops were playing in Nicaragua's economic development. Because co-ops represent grass-roots economic democracy, I hoped to find that co-ops were a significant factor in the Nicaraguan people's attempt to overcome the vast inequalities of wealth and power that were the legacy of the Somoza regime. Based on the support for this visit shown by many Ann Arbor co-ops and credit unions, I also wanted to be able to return with comparisons of how co-ops operate in a Third World country versus the United States, and with some suggestions for ways that Ann Arbor co-ops might be able to provide assistance to our sister cooperatives of the Juigalpa area.

2. Naively, in retrospect, I assumed it would be possible to stay clear of Nicaraguan politics. All in all, Ann Arbor-style cooperatives are relatively non-political beasts, providing their member-owners with such non-profit consumer services as housing, food, child-care and savings accounts. My cultural blinders tempted me to view Nicaraguan cooperatives in the same light.

Unfortunately, a society engaged in land redistribution and establishment of social benefit systems, while fighting off a terrorist war and economic embargo, did not lend itself to this form of analysis. In Nicaragua, every act takes on political shadings. Nearly everything is only one or two steps removed from the war and embargo. Co-ops are not excluded.

My first inkling of this carne in the names of the cooperatives. Instead of University of Michigan Credit Union or Forest Hills Housing Cooperative, Nicaraguan co-ops sport such monikers as the 23rd of August Taxi Cooperative (the completion date of the national adult literacy campaign). There is the Andres Castro Painters Cooperative (the hero of a 19th Century uprising against U.S. intervention) and the Eddy Alonzo Farm Cooperative (an engineer who died in the Sandinista revolution).

Cooperatives also find themselves divided along political lines, rather than being a single unitary movement. The Nicaraguan government places a high priority on private farm cooperatives, which are viewed as a logical alternative to state collectivized farms or dependence on individual landowners. Because these co-ops are located on lands appropriated by the state and redistributed to previously-landless peasants, they are frequent symbolic targets of Contra attacks, and suffer from a lack of capital to purchase machinery to expand production.

Other private cooperatives have learned to live with the government. The Nicaraguan Federation of Credit Unions (FECACNIC), for example, after an initial period of mistrust with the Sandinistas, is now providing various government-sponsored cooperatives with educational programs and technical expertise.

Sadly, some co-ops have not fared so well. In Juigalpa, the local small business cooperatives depended to a great extent on the ongoing largesse of U.S.-originated aid programs. Never having built a strong capital base of its own, this co-op will be forced to cease operating in December.

In summary, I concluded that the cooperative movement is alive and well in Nicaragua - although on very different terms than the U.S. variety. Nicaraguan co-ops are supplier and producer, rather than consumer; they have strong political groundings based in the highly politicized Nicaraguan society; and they tend to be rooted in the practical need to survive in a harsh economic environment, rather than based on any abstract cooperative philosophy.

3. My favorite story illustrates so much of what is happening in Nicaragua - both in its factual details and in the combination of practicality and idealism in a people facing nearly insurmountable odds.

Picture five people - four men and a woman - seated in a newly-constructed hovel, kilometers from anywhere. Their shelter, if it can be termed such, is a ramshackle construction of a few planks nailed together, one wall of piled cinder blocks without mortar, and a detached tin roof weighed down by a few bricks.

Ancient hammocks are slung on both sides of a low wall dividing the men's sleeping area from that of the woman. In the "kitchen," a kettle boils on a fire-pit dug in the ground. Nearby is a hand-mill for grinding corn into meal. Next to it sits a loaded assault rifle.

They are building a new dairy-cattle cooperative.

These are campesinos, not used either to foreigners or philosophizing. Hesitantly they begin to tell their story.

They are the vanguard of nine families that will soon own this cooperative. Until two years ago, they lived on a farm cooperative that supported twenty families. One day the Contras carne and burned their cooperative to the ground, killing many of their compañeros. They were fortunate to be away at the time.

Life has not been easy in the intervening years. One of the men went into the army. Another went to work in a different cooperative. A third tried living in Managua, but couldn't get work. The fourth says he was kidnapped by the Contras and forced to participate in a half-dozen raids before he managed to escape in the middle of the night.

Now they have been given about 220 acres of land, appropriated from a wealthy farmer who was determined by the government not to be an "efficient producer". They are receiving materials from a Dutch foundation to build and fence their farm. Once it is complete, in a month or so, they have been told they will receive 150 dairy cows to start their farm, followed by some beef cattle. Depending on availability, they may actually get far less.

Proudly they walk us around their farm, pointing to the filthy hole in the ground that they use for drinking water. Some day they will have a proper well constructed here. Fortunately there is a river running through the back of the property - their cattle will be able to drink from it. They show us where they will build their homes, and where the fences will go. Today there are just piles of blocks, rails, dirt and barbed wire.

The visitor asks if there are Contras in the area. They point to two hills on the horizon, a few kilometers away. So far, though, the Contras have only attacked on the far side of the nearest town.

A truck pulls up where a supply shed will be built. They must go to unload the wood it is carrying- they've been waiting quite a while for these materials, and it's starting to get dark.

Rev. Virginia Peacock

1. I went to Nicaragua and Juigalpa largely because my congregation wanted me to go and sent me. They wanted a current report from the eyes and ears of someone they knew. I also went out of my own curiosity and as an act of solidarity with the people of Nicaragua through this new Ann Arbor-Juigalpa sister city relationship, although I confess that the last part of this is clearer to me now that I have returned than it was before I left. My curiosity probably was more religiously motivated than politically, although I think there is no real division between the two. I had read about and heard reports of a "new reformation" taking place in Latin America through the movement of Christian base communities within the Roman Catholic Church there. I had heard that religion had been a force in the revolution in Nicaragua. I wanted to sense this new stuff, to feel it, to catch its flavors.

2. It is not always easy to identify and own one's pre-conceived notions. But I did carry some doubts, some fears and suspicions about what l'd find. I was afraid that what l'd wanted to believe about the spirit of the revolution and the new government of Nicaragua had been too cheerfully painted by enthusiastic supporters in this country. What I found, I think, was a genuineness of intention to build something good, a country in which the wellbeing of the people is a true goal, and that (cont. on PAGE 31)

Rev. Virginia Peacock (cont. from page 5)

this desire is shared, despite the presence of some who are embittered, even by many who were among the more privileged prior to the revolution of 1979.

Despite some fear that we might hear only one version of the truth, I was encouraged to find that we were encouraged by officials to talk with anyone we wanted. Thus, it was possible to talk with some who are dissatisfied, disgruntled, unhappy with the state of things in their land. Such people did not seem to fear talking with us. The reality seems to be what the government apparently is confident of, that the continuing revolutionary process has the support of the majority of the people. Wherever this continuing process leads - and there is strong determination that it will continue despite contra tactics of attempting to instill fear among the poorest of the people and to demoralize the spirit of the vision of the new Nicaragua - what we heard over and over again, from people holding a variety of opinions, was the expression of the desire for Nicaraguan self-determination without U.S. interference.

3. My story is not really a story as much as it is an impression gained during a visit to a Christian base community in Juigalpa. These people were shy among us. A woman emerged as their spokesperson. That she was poor showed. She had teeth missing. Yet, she spoke with assurance. She was a woman empowered, even though she had experienced opposition to who she was and what she was about from her bishop (Vega). I was impressed by her courage, her lack of fear.

My experience of this woman stands somewhat in contrast to an experience I had had the evening before which involved the deferment of three women, one, my hostess, a woman of about fifty, very active in her neighborhood, her sister, probably in her thirties, and an older, grandmother-aged woman, who sat in a rocker with a child on her lap, to a man, who clearly had been drinking, and who was trying to impress my Ann Arbor companion and me with his intelligence and knowledge. I had the feeling that the three women probably could run circles around this man under any circumstances.

What I brought home with me about the women of Nicaragua (illustrated in these two experiences together - the one of the poor woman who had had the courage to stand up to the authority of her male bishop, and the other of the three women deferring to the self-important man) is both a distinct impression of the role that empowered women have played and might continue to play in what is going on today in Nicaragua, and a fear that in the course of things this will be lost and it's authority undercut (either through culturally conditioned deferment or through a perceived necessity); especially under the pressures of a war and the strong desire to get on with a task in spite of it. If that does happen, if the importance of the role of the women is lost and their authority lost, there will be something of a betrayal of the vision of a revolution.

Jim Ringold

1. The Reagan administration's continuation of America's immoral policy, of terrorism aimed at civilian populations in Central America has concerned me for some time. As a person of conscience I cannot sit idly by and see my government and my country's tax dollars used to promote the rape, torture and murder of my fellow human beings. For this reason I was attracted to the Proposal A campaign from the beginning. I have been impressed by the wisdom of the task force and by the wisdom of the voters in Ann Arbor for condemning current U.S. policy in Central America and supporting aid to the people of Nicaragua rather than to mercenary terrorists.

I have been doing door to door work for SANE for a year and a half; thus I have discussed some of the issues of the day with over 12,000 people. Though I am more informed about some U.S. policies than most Americans, this isn't saying much. My knowledge of U.S. policy in Central America, for instance, was fairly intellectualized. By joining the sister city delegation I sought to get more of a feeling for the real problems facing Nicaragua so that I could be more effective both in communicating this to the public and in training others in door to door work. In addition, the sister city delegation offered the opportunity to investigate the needs of Juigalpa, to form initial sister city ties, to bring material aid and to have virtually unfettered access to government officials, opposition figures and the people of Nicaragua.

The karma of U.S. will return to us. Let us choose sister cities rather imperialist subjugation.

2. I was aware of the history of U.S. military occupations of the area. I knew that my country had invaded Central America over 50 times, and that some military occupations of Nicaragua had lasted 20 years. I was aware that the U.S. had, among other things, installed several members of the Somoza family following marine invasions. And I was aware that Anastasio D. Somoza had been among the most oppressive of dictators as well as the wealthiest individuals in the world (due to graft).

I supported the popular Sandinista revolution, but I was careful not to "idealize the Sandinistas." I did not want to be accused of following the same path of Russian revolution sympathizers who were seemingly blind to Stalin's abuses. I was prepared to understand the complexities of the situation rather to be a "Sandinista ho" sort of person.

After extensive talks with a wide range of ordinary Nicaraguans, government officials, opposition forces, and the U.S. embassy, I now find myself firmly in support of the Sandinista party and the popular Sandinista army as well as the revolution. Though I personally aspire to nonviolence, I can understand how ironic this suggestion would be coming from an American.

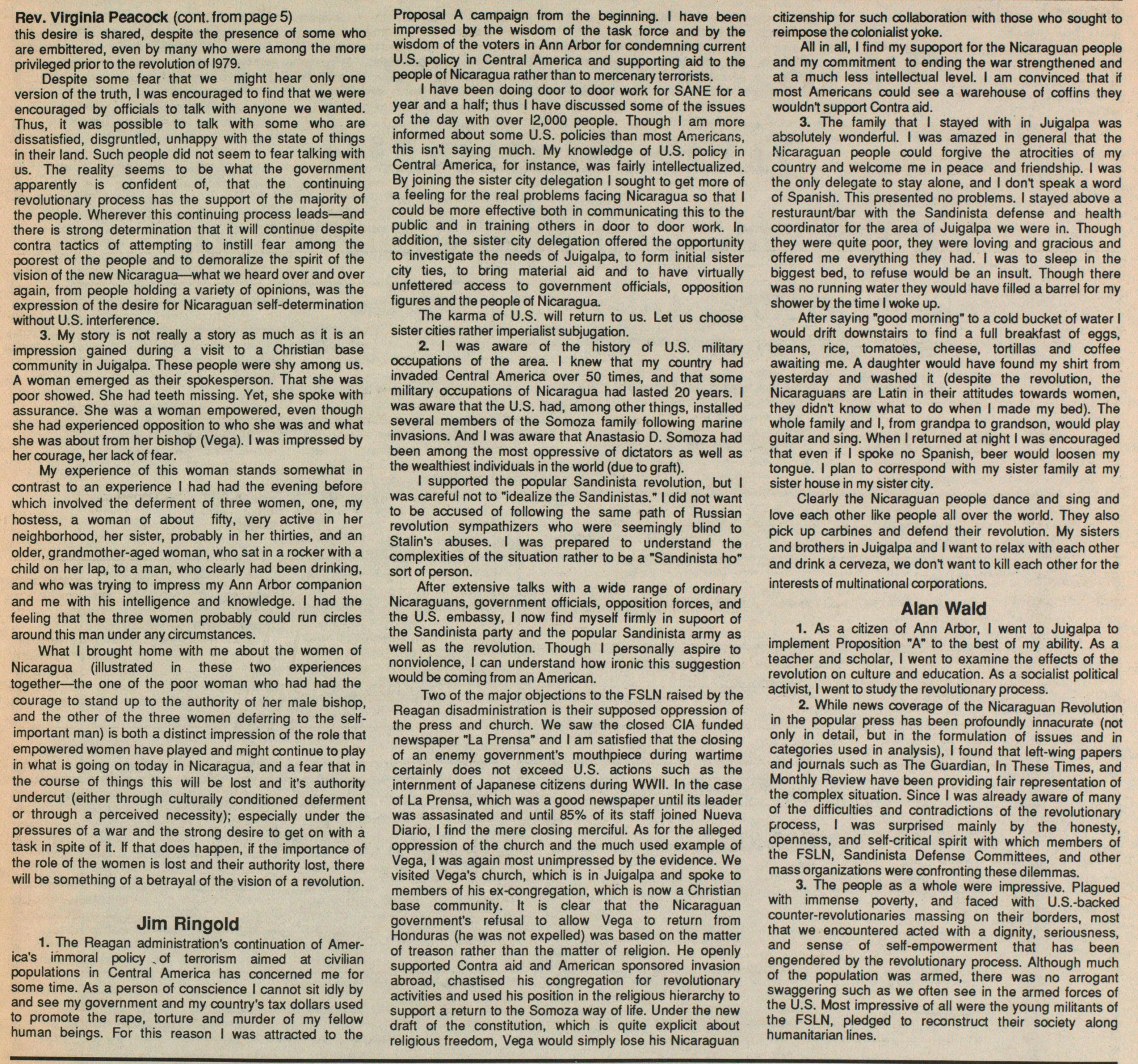

Two of the major objections to the FSLN raised by the Reagan disadministration is their supposed oppression of the press and church. We saw the closed CIA funded newspaper "La Prensa" and I am satisfied that the closing of an enemy government's mouthpiece during wartime certainly does not exceed U.S. actions such as the internment of Japanese citizens during WWII. In the case of La Prensa, which was a good newspaper until its leader was assassinated and until 85% of its start joined Nueva Diario, I find the mere closing merciful. As for the alleged oppression of the church and the much used example of Vega, I was again most unimpressed by the evidence. We visited Vega's church, which is in Juigalpa and spoke to members of his ex-congregation, which is now a Christian base community. It is clear that the Nicaraguan government's refusal to allow Vega to return from Honduras (he was not expelled) was based on the matter of treason rather than the matter of religion. He openly supported Contra aid and American sponsored invasion abroad, chastised his congregation for revolutionary activities and used his position in the religious hierarchy to support a return to the Somoza way of life. Under the new draft of the constitution, which is quite explicit about religious freedom, Vega would simply lose his Nicaraguan citizenship for such collaboration with those who sought to reimpose the colonialist yoke.

All in all, I find my support for the Nicaraguan people and my commitment to ending the war strengthened and at a much less intellectual level. I am convinced that if most Americans could see a warehouse of coffins they wouldn't support Contra aid.

3. The family that I stayed with in Juigalpa was absolutely wonderful. I was amazed in general that the Nicaraguan people could forgive the atrocities of my country and welcome me in peace and friendship. I was the only delegate to stay alone, and I don't speak a word of Spanish. This presented no problems. I stayed above a restaurant/bar with the Sandinista defense and health coordinator for the area of Juigalpa we were in. Though they were quite poor, they were loving and gracious and offered me everything they had. I was to sleep in the biggest bed, to refuse would be an insult. Though there was no running water they would have filled a barrel for my shower by the time I woke up.

After saying "good morning" to a cold bucket of water I would drift downstairs to find a full breakfast of eggs, beans, rice, tomatoes, cheese, tortillas and coffee awaiting me. A daughter would have found my shirt from yesterday and washed it (despite the revolution, the Nicaraguans are Latin in their attitudes towards women, they didn't know what to do when I made my bed). The whole family and I, from grandpa to grandson, would play guitar and sing. When I returned at night I was encouraged that even if I spoke no Spanish, beer would loosen my tongue. I plan to correspond with my sister family at my sister house in my sister city. Clearly the Nicaraguan people dance and sing and love each other like people all over the world. They also piek up carbines and defend their revolution. My sisters and brothers in Juigalpa and I want to relax with each other and drink a cerveza, we don't want to kill each other for the interests of multinational corporations.

Alan Wald

1. As a citizen of Ann Arbor, I went to Juigalpa to implement Proposition "A" to the best of my ability. As a teacher and scholar, I went to examine the effects of the revolution on culture and education. As a socialist political activist, I went to study the revolutionary process.

2. While news coverage of the Nicaraguan Revolution in the popular press has been profoundly inaccurate (not only in detail, but in the formulation of issues and in categories used in analysis), I found that left-wing papers and journals such as The Guardian, In These Times, and Monthly Review have been providing fair representation of the complex situation. Since I was already aware of many of the difficulties and contradictions of the revolutionary process, I was surprised mainly by the honesty, openness, and self-critical spirit with which members of the FSLN, Sandinista Defense Committees, and other mass organizations were confronting these dilemmas.

3. The people as a whole were impressive. Plagued with immense poverty, and faced with U.S.-backed counter-revolutionaries massing on their borders, most that we encountered acted with a dignity, seriousness, and sense of self-empowerment that has been engendered by the revolutionary process. Although much of the population was armed, there was no arrogant swaggering such as we often see in the armed forces of the U.S. Most impressive of all were the young militants of the FSLN, pledged to reconstruct their society along humanitarian lines.

Article

Subjects

Sister City

Old News

Agenda