Anatomy Of A Grassroots Victory: People 1, Cars 0

Score one for people! And score one for people-power too! The Kline's lot parking structure is dead and the people of Ann Arbor can thank the Homeless Action Committee (HAC) for its demise. "Just when it looked as if we had totally failed, we had our greatest success," HAC-member Jeff Gearhart told AGENDA.

HAC' s greatest success came last month when city council voted 6-5 to squelch financing for the proposed $8.7 million parking structure on the corner of William St. and S. Ashley (behind Kline's Department Store). The vote caps a three-year struggle by HAC to kill the project and make the city redirect its money to the housing needs of low-income and no-income people. If the city could find millions of dollars to build a parking structure downtown, HAC argued, it could find money to build low-income housing and take better care of its homeless citizens.

HAC's message was a powerful one. So powerful that when former Mayor Jerry Jemigan asked voters to make the April city elections a referendum on the Kline's parking structure, they responded by voting Jemigan out of office. Not only did the mayor get the boot, but pro-Kline's parking structure councilmembers Jerry Schleicher, R-Fourth Ward, and Joe Borda, R-Fifth Ward, lost their seats as well.

The Democrats, led by longtime HAC supporter and then-Third Ward councilmember Liz Brater, won five of six council races in the April 1 showdown and now control city council with an 8-3 majority. Mayor Brater publicly credited opposition to the Kline's parking structure as a major factor in her win. And many people credit the "historic" landslide of the Democrats in the election directly to the actions of HAC.

HAC' s persistence and creativity in pursuit of a needed change in public policy is a portrait of courage, and selfless sacrifice and dedication. Since its founding in November 1987, HAC has consistently and aggressively - some would say militantly - brought the issue of low-income housing and the plight of the homeless to the public 's attention.

HAC protested. HAC lobbied city council week after week. HAC took over two city-owned houses and occupied them for over a year. HAC marched and picketed. HAC took over city council. HAC held rallies and vigils. HAC had teach-ins and workshops. HAC shut down parking at the current Kline's lot - three times. HAC built coalitions and co-sponsored events with other groups. HAC networked. HAC raised money with benefits and bucket drives. HAC worked and they worked hard.

HAC's membership is a loose coalition of permanent Ann Arbor residents, students, and homeless or formerly-homeless people. The group became interested in the proposed parking structure in January 1989 when it learned that the city, through its Downtown Development Authority (DDA), planned an $8.7 million bond sale to finance the project.

"HAC plans to begin continuous actions at the parking lot to demonstrate against this misuse of city funds," writes HAC-member N. Renuka Uthappa in the February 1989 AGENDA. "HAC hopes to convince the city government to open up the DDA fund and make allocations for low-income housing. HAC will disrupt business as usual until they do so. If necessary, HAC will block the construction of the parking structure."

HAC's first major action, building a shantytown in the parking lot where the planned parking structure will stand, is set for a Saturday, when many shoppers come downtown. Nearly 100 people attend the rally which includes speakers firom the homeless shelter and the community.

"On April 15, 1989 we arrive at the lot at 7:00 am, with large cardboard boxes to 'park' in the lot,"HAC-member Laura Dresser writes in a recently reconstructed diary of events. "The boxes are a visual reminder of the living conditions of homeless people in the city. While people sleep in the cold, the city plans for an unneeded and expensive parking structure. Our blockades in front of the entrances to the lot remind people of the many empty parking spaces in parking structures only two blocks away. We spend the morning painting slogans and art on boxes that fill the lot wondering how the merchants will respond.

"Though we are prepared for possible arrest by attending a four-hour civil disobedience training the week before, the police do not interrupt the takeover. City merchants near the lot are upset and come out often to look at the protest and exchange a few angry words. The takeover ends victoriously at 4:00 pm when HAC takes down the boxes and opens up the lot. A front-page color photo and story in the Sunday Ann Arbor News covers the protest"

HAC spends the next several months picketing the Kline's lot each Saturday, distributing fliers at the popular summer movie series, "Top of the Park," and painting slogans on sidewalks around the city. During this time HAC members regularly attend city council meetings to speak during audience participation time, criticizing the city's continuing committment to the Kline's parking structure.

"Audience participation time speakers from HAC address different issues regarding city development and housing," the HAC diary reads. "We use this time to establish and project our analysis of city actions and plans to both the council and the larger public through the Community Access TV channel which broadcasts all council meetings live. Topics range from the 'need' for parking structures to the treatment of homeless people to the misuse of taxpayers money. Different people are encouraged to speak each week which develops our core of speakers and broadens our strength in the eyes of council members.

"Also during this period other individuals and groups begin to speak out in support of HAC and our demands (specifically the Grey Panthers send one speaker to each meeting)."

HAC's next move is perhaps its boldest of the entire anti-parking structure campaign. On Nov. 13, 1989, members of HAC begin an illegal squat of the house at 337 S. Ashley, one of three houses on the northeast corner of W. William and S. Ashley scheduled for demolition by the city to make way for the project.

"We will open the deserted house and use it as a home for HAC members and homeless people and as a center for our organizing," the HAC diary reads. "Not only will the house provide a home for people who need it, and an office for HAC, but it will also directly confront the city's plans to destroy housing for the parking structure.

"We have a rally at city hall which is followed by a march to the house and an 'open house' party inside. Arrangements for (see HAC, page 7)

Homeless Action Committee (from pag one) a generator and propane heater have been made and some HAC members and homeless folks stay overnight. The squat of 337 S. Ashley provokes support and interest from the community. Churches, businesses, political groups and individuals donate blankets, canned food, meals, and space heaters. Our group and network of supporters grows."

With one house under their control, HAC keeps up the pressure on city council by conducting a "People's Council" in city council chambers during city council time. One week after their squat of "Day One," HAC members forcefully occupy the chairs of councilmembers for the first 30 minutes of council's regular Monday night meeting.

"Our People's Council of 13 includes four people who live in Day One," the HAC diary reads. "The meeting is called to order by one person who, only a week before, lived in a shelter. Each councilmember reads from a script about development and homelessness in the city. We present to the public four resolutions for city action. Over 100 supporters come to the meeting and chant 'House People, Not Cars!' in approval of our people's agenda for housing and downtown development

"Again we are not arrested. The Democrats on the council do not object to the action, while the Republicans, for the most part, are annoyed. In fact one Republican councilmember orders the worker from Community Access TV to stop their broadcast during the action. After we turn the seats over to the council the regular meeting begins and HAC members again ask that the Ann Arbor housing crisis be dealt with. The following day, The Ann Arbor News covers the council takeover with a front page story which includes quotes from our speeches and script and details of our four resolutions."

The squat of 337 S. Ashley in the winter of 1989 proves to be a diffïcult but rewarding task for HAC. "The house has neither heat nor water," the HAC diary reads, "and while space heaters offer some warmth they are no match for the deep cold of a Michigan winter. Water for drinking is obtained from a supporter next door, but neither hot water, nor showers, nor flush toilets are available to those in the house.

"In addition to these physical hardships, the work of the house is incredibly time-consuming, disillusioning and stressful. Though it is a diffïcult time, it also brings new members to the group. Support and recognition from the public also grows. And our committment to the squat, in spite of the considerable difficulties, shows to city council, the community, and ourselves the depth of our strength and support."

In early January 1990 HAC finally gets a long-asked for meeting with city council in a special Friday session devoted exclusively to housing. HAC puts its platform before council and a packed room of over 130 people. Council listens but does not act. Unsatisfied, HAC launches a series of actions aimed at influencing city council. In late January they march from Day One to city hall to demand a meeting with Mayor Jemigan. They don't get one. In February HAC places a shanty on the lawn of city hall symbolizing, they say, the conditions of those who have to live on the streets. Media coverage of these events is significant.

HAC continues to hold meetings in Day One, which now has a smaller but more permanent number of residents. On April 5, 1990 HAC begins their second squat by moving into a vacant house at 116 W. William, one of the three houses set to be destroyed for the parking structure. "For this squat, we have arranged to work closely with social workers and the residents because we are committed that the house become a permanent and stable home," reads the HAC diary. "Again we make a political point while we provide a real service to the families affected.

"One of the families that moved in has three small children. The other is a man, a woman who is pregnant and her child. Media coverage for the people in the house is almost overwhelming. Stories in four newspapers (The Ann Arbor News, Agenda, The Observer, and Detroit Free Press) include interviews with the residents. People in the area read about the personal suffering and hardship of homelessness and the squat on city property . Homelessness is given a human face at the same time it is placed in the center of city politics."

Media coverage of HAC is plentiful at this point but not always favorable. The Ann Arbor News editorializes against the lawless actions of HAC and demands that city council take action against them. The city shuts off water at 116 W. William at one point and even changes the locks on the doors when residents are away from the house. Nontheless, no one is ever arrested and the two squatted houses remain occupied until early 1991.

Through the summer and fall of 1990 HAC sponsors another takeover of the current Kline's lot, holds a benefit concert, cosponsors a travelling theater group, and continues to build alliances with other groups in town. HAC also temporarily turns its attention to the vacant Ann Arbor Inn. HAC members attend city hearings to advocate using the Inn for low-income housing.

But HAC is forced to refocus its energy on the houses and parking structure as the inevitable eviction process against the squatters begins in earnest in September. In November the remaining resident of Day One, who has lived in the house for more than a year, moves into 116 W. William. Day One has provided a shelter and home to dozens during the squat but is now unheatable and unsafe and the group conducts a service of "last rites" for the house a few nights before it is demolished.

The eviction process at 116 W. William is another story. After exhausting all legal appeals, a crowd of HAC supporters gathers on eviction day at the house, on a cold mid-February morning, vowing not to give up the house without resistance.

At the last moment Mayor Jemigan strikes a deal with HAC, brokered by Democratic councilmembers Ann Marie Coleman and Thais Peterson. The mayor agrees to vote for a resolution that would turn the remaining two houses over to a nonprofit housing agency and provide city finances for the moving and rehabilitation of the homes. HAC agrees to leave the house (when it is ready to be moved) without protest. The houses, containing 11-units, are eventually sold by the city to the Shelter Association of Ann Arbor for $1 per house.

In early February HAC asks city council to let the voters decide the fate of the Kline's parking structure by putting the issue on the April 1 ballot The council denies the resolution by a 7-4 vote. Then what appears to be a major setback to HAC's cause, an 8-3 council vote on March 4 to begin to sell city bonds for the parking structure, actually provides yet another mechanism for HAC to organize around.

HAC responds immediately by launching a petition drive aimed at putting the bond issue to a citywide vote. By law, HAC faces a 45-day deadline to collect about 8,000 signatures (10% of registered voters) to force a special election.

The April 1, 1991 city elections change everything. Instead of having to lobby a city council with a 6-5 Republican majority, HAC now faces a more sympathetic city council, stacked with an 8-3 Democratie majority.

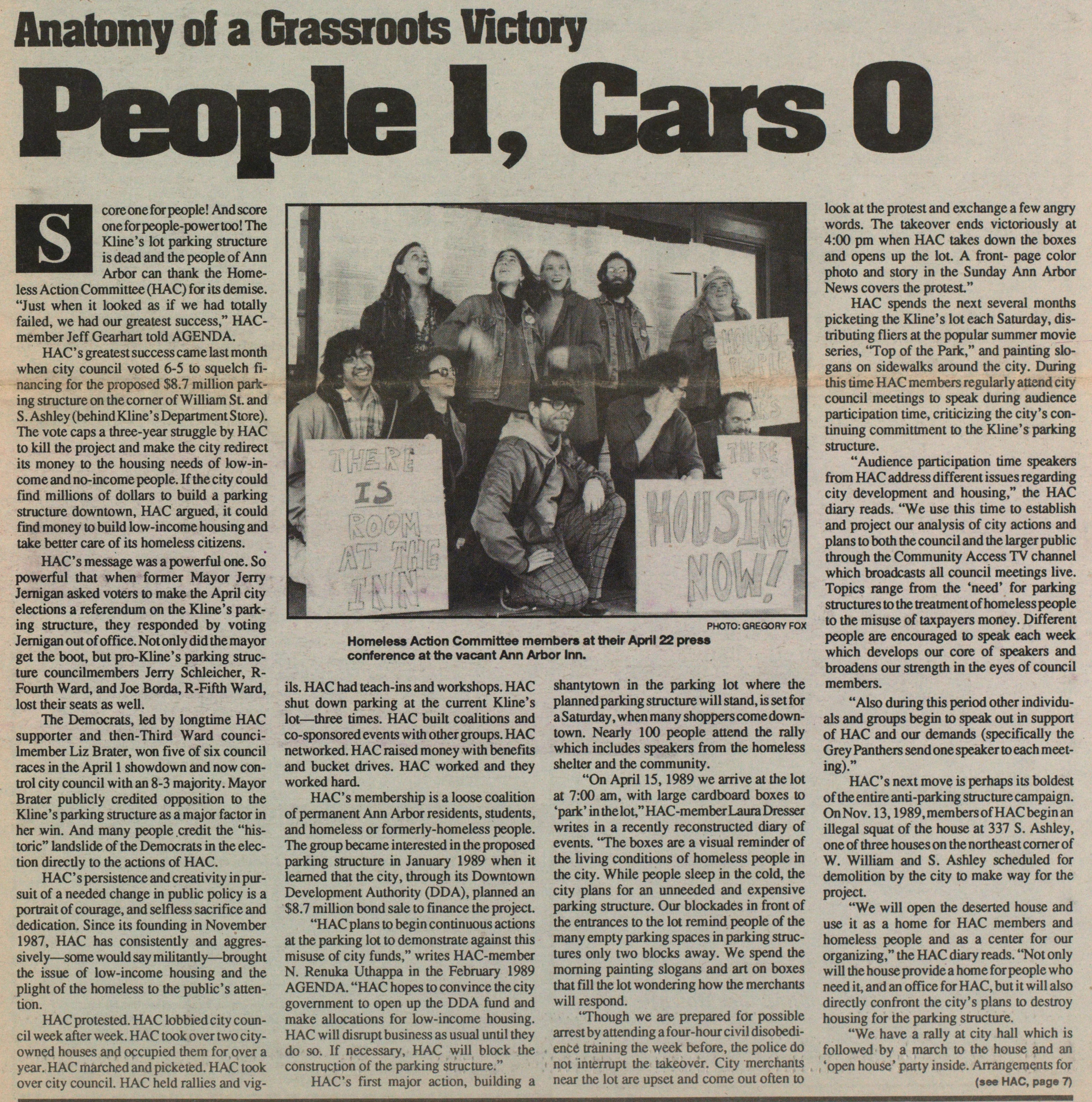

The rest is history. At an April 22 press conference at the vacant Ann Arbor Inn, HAC tapes their petitions on the doors with 4,800 signatures, a significant show of support but not enough to force the referendum. A week later HAC lobbies city council to hold the advisory election anyway. Council votes 6-5 in favor and the referendum is set for June 24. Council also votes to halt the sale of bonds for the project pending the outcome of the election.

A week later. Mayor Brater surprises everyone by announcing that the special election is off, and that she will veto any future council resolutions that authorize selling city bonds for the Klines parking structure. What appears to be the final vote on the matter comes May 20 when city council votes 6-5 to not sell bonds for the parking structure.

With the Kline's parking structure dead, HAC plans to spend more time pursuing their ultimate goal: housing for people who can't afford it. HAC's story should serve as inspiration for all who work for social and political change. It proves that you don't need to be a politician or have big money on your side in order to prevail in the public arena. HAC's story also proves that courage and determination, coupled with an unwillingness to accept roadblocks as failures, are essential to ultímate victory.

by Ted Sylvester