Berkeley in the '60s

{picture of cops and protesters}

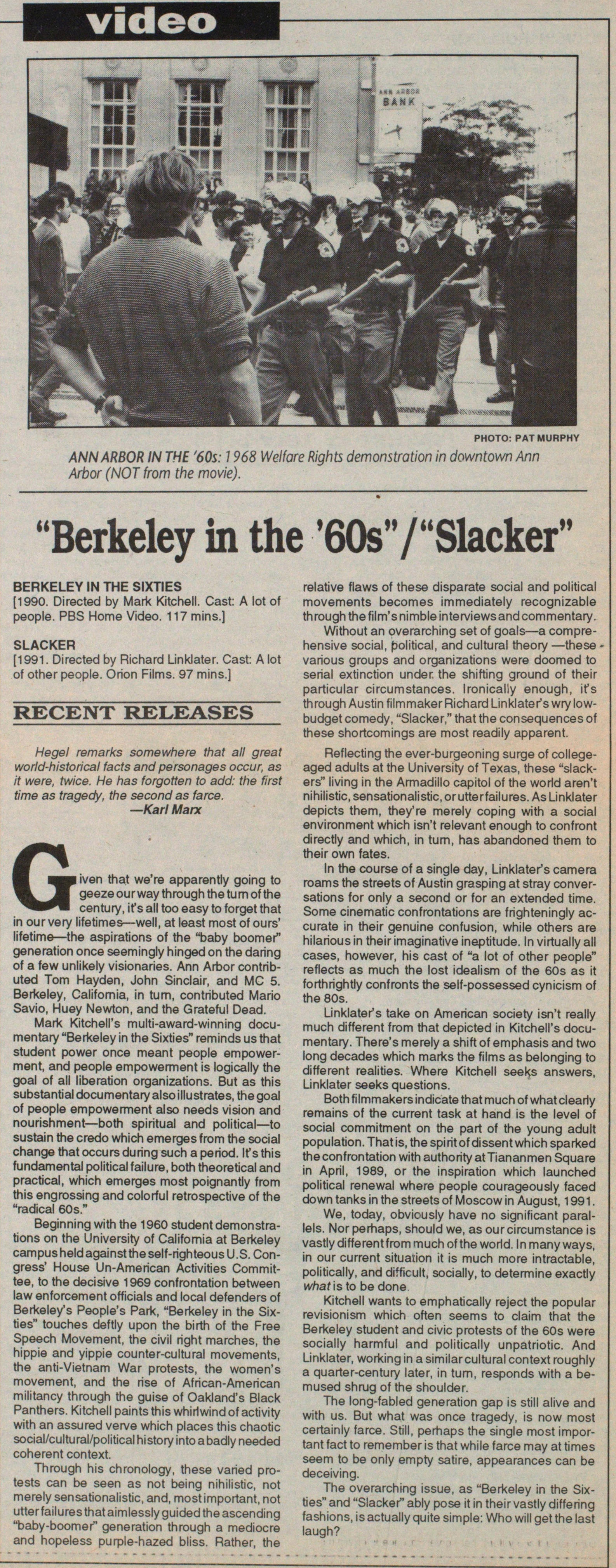

ANN ARBOR IN THE '60s: 1968 Welfare Rights demonstration in down Ann Arbor (NOT from the movie).

"Berkeley in the '60s" / "Slacker"

BERKELEY IN THE SIXTIES

[1990. Directed by Richard Linklater. Cast: A lot of other people. Orion Films. 97 mins.]

RECENT RELEASES

Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historical facts and personages occur, as it were, twice. He has forgotten to add: the first time as tragedy, thesecond as farce.

--Karl Marx

Given that we're apparently going to geeze our way through the turn of the century, it's all too easy to forget that in our very lifetimes--well, at least most of ours' lifetime--the aspirations of the "baby boomer" generation once seemingly hinged on the daring of a few unlikely visionaries. Ann Arbor contributed Mario Savio, Huey Newton, and the Grateful Dead.

Mark Kitchell's multi-award-winning documentary "Berkeley in the Sixties" reminds us that student power once meant people empowerment, and people empowerment is logically the goal of all liberation organizations. But as this substantial documentan also illustrates, the goal of people empowerment also needs vision and nourishment - both spiritual and political - to sustain the credo which emerges from the social change that occurs during such a period. It's this fundamental political failure, both theoretical and practical, which emerges most poignantly from this engrossing and colorful retrospective of the "radical 60s."

Beginning with the 1960 student demonstrations on the University of California at Berkeley campus held against the self-righteous U.S. Congress' House of Un-American Activities Committee, to the decisive 1969 confrontation between law enforcement officials and local defenders of Berkeley's People's Park, "Berkeley in the Sixties" touches deftly upon the birth of the Free Speech Movement, the civil right marches, the hippie and yippie counter-cultural movements, the anti-Vietnam War protests, the women's movement, and the rise of African-American militancy through the guise of Oakland's Black Panthers. Kitchell paints this whirlwind of activity with an assured verve which places this chaotic social/cultural/political history into a badly needed coherent context.

Through his chronology, these varied protests can be seen as not being nihilistic, not merely sensationalistic, and, most important, not utter failures that aimlessly guided the ascending "baby-boomer" generation through a mediocre and hopeless purple-hazed bliss. Rather, the relative flaws of these disparate social and political movements becomes immediately recognizable through the film's nimble interviews and commentary.

Without an overarching set of goals - a comprehensive social, political, and cultural theory - these various groups and organizations were doomed to serial extinction under the shifting ground of their particular circumstances. Ironicaliy enough, it's through Austin filmmaker Richard Linklater's wry low budget comedy, "Slacker," that the consequences of these shortcomings are most readily apparent.

Reflecting the ever-burgeoning surge of college-aged adults at the University of Texas, these "slackers" living in the Armadillo capítol of the world aren't nihilistic, sensationalistic, or utter failures. As Linklater depicts them, they're merely coping with a social environment which isn't relevant enough to confront directly and which, in turn, has abandoned them to their own fates.

In the course of a single day, Linklater's camera roams the streets of Austin grasping at stray conversations for only a second or for an extended time. Some cinematic confrontations are frighteningly accurate in their genuine confusion, while others are hilarious in their imaginative ineptitude. In virtually all cases, however, his cast of "a lot of other people" reflects as much the lost idealism of the 60s as it forthrightly confronts the self-possessed cynicism of the 80s.

Linklater's take on American society isn't really much different from that depicted in Kitchell's documentary. There's merely a shift of emphasis and two long decades which marks the films as belonging to different realities. Where Kitchell seeks answers, Linklater seeks questions.

Both filmmakers indicate that much of what clearly remains of the current task at hand is the level of social commitment on the part of the young adult population. That is, the spirit of dissent which sparked the confrontation with authority at Tiananmen Square in April, 1989, or the inspiration which launched political renewal where people courageously faced down tanks in the streets of Moscow in August, 1991.

We, today, obviously have no significant parallels. Nor perhaps, should we, as our circumstance is vastly different from much of the world. In many ways, in our current situation it is much more intractable, politically, and diíficult, socially, to determine exactly what is to be done.

Kitchell wants to emphatically reject the popular revisionism which often seems to claim that the Berkeley student and civic protests of the 60s were socially harmful and politically unpatriotic. And Linklater, working in a similar cultural context roughly a quarter-century later, in turn, responds with a bemused shrug of the shoulder.

The long-fabled generation gap is still alive and with us. But what was once tragedy, is now most certainly farce. Still, perhaps the single most important fact to remember is that while farce may at times seem to be only empty satire, appearances can be deceiving.

The overarching issue, as "Berkeley in the Sixties" and "Slacker" ably pose it in their vastly differing fashions, is actually quite simple: Who will get the last laugh?