Rebellion In Mexico

Rebellion in Mexico

Zapatistas Take Aim at NAFTA

By Eric Jackson

"General, what's going on in San Cristobal? There's a lot of people..."

"I don't know. They aren't people celebrating the New Year?"

- phone call to Military Region XXXI, 1:45 a.m. January 1

Few U.S. and Canadian factory owners seem eager to run away to Latin America's newest war zone and pay taxes to a rebel army.

Despite all of the news coverage about Mexico during last year's NAFTA debate, a New Year's Day rebel offensive in Chiapas caught most North Americans unaware. Those whose main images of Mexico are the allegedly growing markets which dominated the discussion of NAFTA probably won't understand the far-reaching political consequences of the uprising in Mexico's breadbasket.

Yet on both sides of the Rio Grande, those who know the history of U.S.-Mexican relations realize that the stakes are high. The last time that Mexico had a revolution, Woodrow Wilson sent the Marines into Veracruz and Tampico, and dispatched General John J. "Blackjack" Pershing on a long and fruitless chase after Pancho Villa. It didn't work then, but if the unpopular Mexican government loses its grip on the country, or seems about to do so, President Clinton may be tempted to fix broken NAFTA dreams with military intervention.

Rarely have Mexican peasants had as much to complain about as this past New Year's Day, when NAFTA went into effect. An influx of cheap U.S.-produced food is expected to drive many of them out of the market and off of their land. Economist Thea Lee, a former Ann Arborite and researcher with the Economic Policy Institute, estimated in the January 1993 AGENDA that 800,000 to 2 million Mexican farmers will be displaced. Comandante Marcos, who led the rebel attack on San Cristóbal, openly stated the NAFTA connection: "It's clear the date is related to NAFTA, which for the Indians is a death sentence. Once it goes into effect, it means an international massacre."

In the rebellious zones of Chiapas, pressure on indigenous farmers is especially acute. Since ancient times until recent decades, the Lacandon and other descendants of the Mayas owned and farmed their land communally. Yet to integrate Mexico into the world economy, the government divided the land among individuals, imposed taxes and other policies to force a change from subsistence to cash crop farming, then left the small farmers without the roads, equipment, fertilizers or credit to compete in modern agribusiness. The predictable foreclosures of traditional Mayan lands drove many into the wilderness to make way for cattle ranches and mechanized, chemical-based corporate vegetable farming. When the Lacandon and others retreated to the jungle to slash and burn new subsistence farms, big landowners backed by gunstingers and holding titles obtained from corrupt officials, showed up to take that land, too.

One result is that Chiapas is one of Mexico's principal food-exporting regions. Another result is that Chiapanecos (what the state's natives call themselves) are among the poorest in a poor country. In Chiapas, some 80% of the houses have dirt floors. Despite the presence of hydroelectric dams which provide three-fifths of Mexico's power, more than one-third of the state's communities have no electricrty. With one doctor per each 1,500 of the state's three million residents, some 15,000 people die from preventable diseases every year in Chiapas.

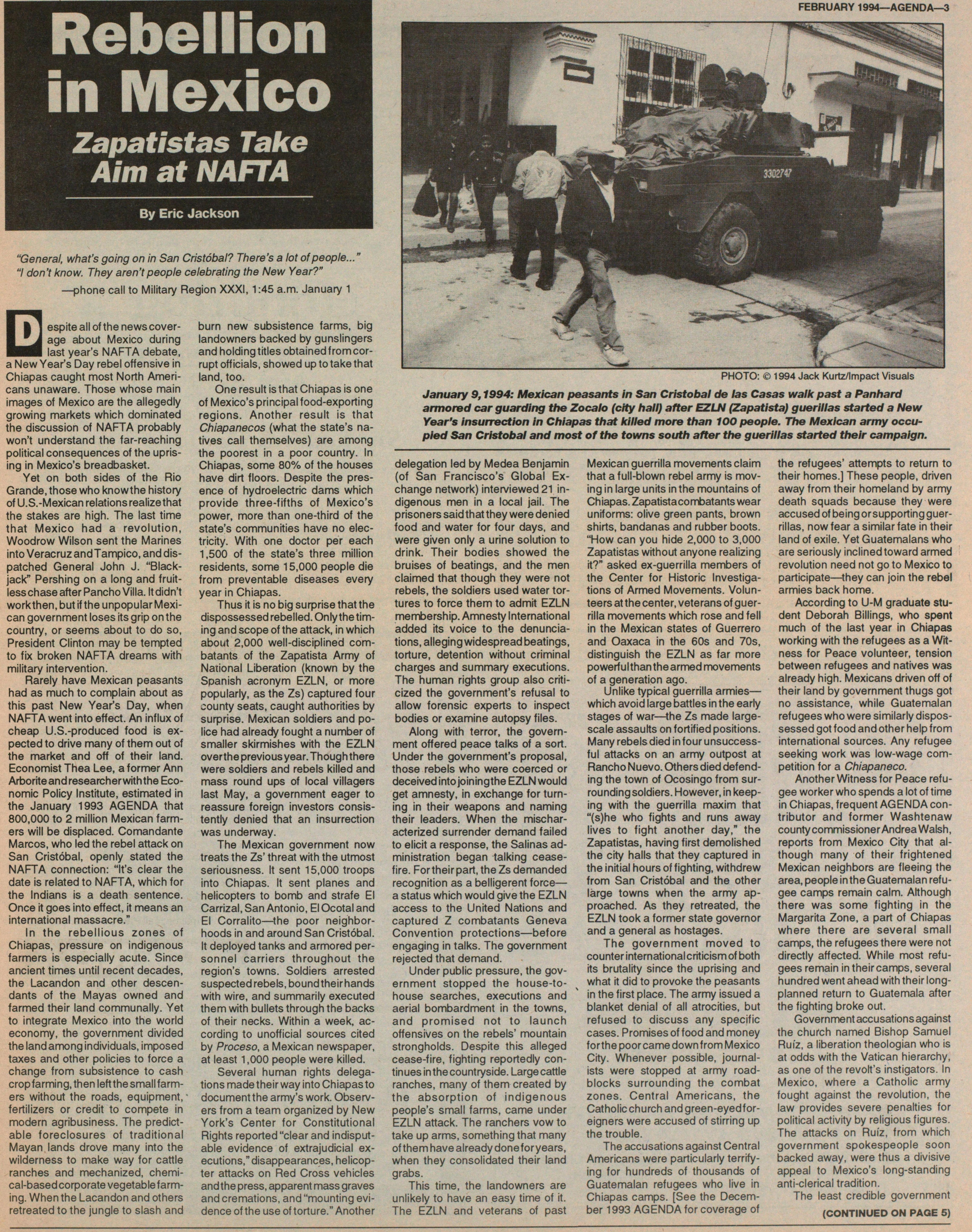

Thus it is no big surprise that the dispossessed rebelled. Only the timing and scope of the attack, in which about 2,000 well-disciplined combatants of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (known by the Spanish acronym EZLN, or more popularly, as the Zs) captured four county seats, caught authorities by surprise. Mexican soldiers and police had already fought a number of smaller skirmishes with the EZLN overthe previous year. Though there were soldiers and rebels killed and mass round ups of local villagers last May, a government eager to reassure foreign nvestors consistently denied that an insurrection was underway.

The Mexican government now treats the Zs' threat with the utmost seriousness. It sent 15,000 troops into Chiapas. It sent planes and helicopters to bomb and strafe El Carrizal, San Antonio, El Ocotal and El Corralito - the poor neighborhoods in and around San Cristóbal. It deployed tanks and armored personnel carriers throughout the region's towns. Soldiers arrested suspected rebels, bound their hands with wire, and summarily executed them with bullets through the backs of their necks. Within a week, according to unofficial sources cited by Proceso, a Mexican newspaper, at least 1,000 people were killed.

Several human rights delegations made their way into Chiapas to document the army's work. Observers from a team organized by New York's Center for Constitutional Rights reported "clear and indisputable evidence of extrajudicial executions," disappearances, helicopter attacks on Red Cross vehicles and the press, apparent mass graves and cremations, and "mounting evidence of the use of torture." Another delegation led by Medea Benjamin (of San Francisco's Global Exchange network) interviewed 21 indigenous men in a local jail. The prisoners said that they were denied food and water for four days, and were given only a urine solution to drink. Their bodies showed the bruises of beatings, and the men claimed that though they were not rebels, the soldiers used water tortures to force them to admit EZLN membership. Amnesty International added its voice to the denunciations.alleging widespread beatings, torture, detention without criminal charges and summary executions. The human rights group also criticized the govemment's refusal to allow forensic experts to inspect bodies or examine autopsy files.

Along with terror, the government offered peace talks of a sort. Under the govemment's proposal, those rebels who were coerced or deceivedintojoiningtheEZLNwould get amnesty, in exchange for turning in their weapons and naming their leaders. When the mischaracterized surrender demand failed to elicit a response, the Salinas administration began talking ceasefire. For their part the Zs demanded recognition as a belligerent force - a status which would give the EZLN access to the United Nations and captured Z combatants Geneva Convention protections - before engaging in talks. The government rejected that demand.

Under public pressure, the government stopped the house-to-house searches, executions and aerial bombardment in the towns, and promised not to launch offensives on the rebels' mountain strongholds. Despite this alleged cease-fire, fighting reportedly continues in the countryside. Large cattle ranches, many of them created by the absorption of indigenous people's small farms, came under EZLN attack. The ranchers vow to take up arms, something that many of them have already done for years, when they Consolidated their land grabs.

This time, the landowners are unlikely to have an easy time of it. The EZLN and veterans of past Mexican guerrilla movements claim that a full-blown rebel army is moving in large units in the mountains of Chiapas. Zapatista combatants wear uniforms: olive green pants, brown shirts, bandanas and rubber boots. "How can you hide 2,000 to 3,000 Zapatistas without anyone realizing it?" asked ex-guerrilla members of the Center for Historie Investigations of Armed Movements. Volunteers at the center, veterans of guerrilla movements which rose and feil in the Mexican states of Guerrero and Oaxaca in the 60s and 70s, distinguish the EZLN as far more powerfuI than the armed movements of a generation ago.

Unlike typical guerrilla armies - which avoid large battles in the early stages of war - the Zs made largescale assaults on fortified positions. Many rebels died in four unsuccessful attacks on an army outpost at Rancho Nuevo. Others died defending the town of Ocosingo from surrounding soldiers. However, in keeping with the guerrilla maxim that "(s)he who fights and runs away lives to fight another day," the Zapatistas, having first demolished the city halls that they captured in the initial hours of fighting, withdrew from San Cristóbal and the other large towns when the army approached. As they retreated, the EZLN took a former state governor and a general as hostages.

The government moved to counter international criticism of both its brutality since the uprising and what it did to provoke the peasants in the first place. The army issued a blanket denial of all atrocities, but refused to discuss any specific cases. Promises of food and money forthe poor came down from Mexico City. Whenever possible, journalists were stopped at army road-blocks surrounding the combat zones. Central Americans, the Catholic church and green-eyed foreigners were accused of stirring up the trouble.

The accusations against Central Americans were particularly terrifying for hundreds of thousands of Guatemalan refugees who live in Chiapas camps. [See the December 1993 AGENDA for coverage of the refugees' attempts to return to their homes.] These people, driven away from their homeland by army death squads because they were accused of being or supporting guerrillas, now fear a similar fate in their land of exile. Yet Guatemalans who are seriously inclined toward armed revolution need not go to Mexico to participate - they can join the rebel armies back home.

According to U-M graduate student Deborah Billings, who spent much of the last year in Chiapas working with the refugees as a Witness for Peace volunteer, tension between refugees and natives was already high. Mexicans driven off of their land by government thugs got no assistance, while Guatemalan refugees who were similarly dispossessed got food and other help from international sources. Any refugee seeking work was low-wage competition for a Chiapaneco.

Another Witness for Peace refugee worker who spends a lot of time in Chiapas, frequent AGENDA contributor and former Washtenaw county commissioner Andrea Walsh, reports from Mexico City that although many of their frightened Mexican neighbors are fleeing the area, people in the Guatemalan refugee camps remain calm. Although there was some fighting in the Margarita Zone, a part of Chiapas where there are several small camps, the refugees there were not directly affected. While most refugees remain in their camps, several hundred went ahead with their long planned return to Guatemala after the fighting broke out.

Government accusations against the church named Bishop Samuel Ruíz, a liberation theologian who is at odds with the Vatican hierarchy, as one of the revolt's instigators. In Mexico, where a Catholic army fought against the revolution, the law provides severe penalties for political activity by religious figures. The attacks on Ruíz, from which government spokespeople soon backed away, were thus a divisive appeal to Mexico's long-standing anti-clerical tradition.

The least credible government

(CONTINUED ON PAGE 5)

Rebellion in Mexico

(From Page 3)

ploy is foreigner-bashing. The present regime sells national assets (for example, the phone company) to foreigners at a pace not seen since the days of Porfirio Díaz. Many Mexican observers compare the technocrats around President Salinas with Diaz's "científico" advisors, then the most effective theoristsnand administrators that foreign companies could buy. After NAFTA, tales of blonde-haired green-eyed bogeymen might just ring true - but not if told by the dentified government.

Walsh reports that the Zapatistas represent a large part of the population. One indicator of the Zs' true threat is the reaction throughout Mexico. Less than two weeks after the fighting began, 80,000 to 100,000 Mexicans marched in the capital, demanding a negotiated end to the crisis. Along with EZLN-claimed power line bombings in the central states of Puebla and Michoacan, a number of apparently unaffiliated groups set off bombs in the capital. Comandante Marcos, who is neither indigenous nor from Chiapas, objected to organizations of the EZLN as local: "Our movement," said the commander, "is not Chiapaneco, 'A is national. There are people like me, who come from other states, and Chiapanecos who fight in other states. We are Mexicans." While the Zapatista military threat seems for nowto be mainly confined to Chiapas, its political challenge casts a much larger shadow.

The threat that the rebels pose to the longruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) looms even larger when one takes Mexican history into account. Indigenous peasant armies were part of every Mexican revolution. The war of independence against Spain began when peasants led by Father Hidalgo went on a bloody rampage against foreign landowners. The indigenous Oaxacan lawyer Benito Juárez led the peasants to defeat Emperor Maximilian, an Austrian prince imposed by the homegrown aristocracy. When dictator Porfirio Díaz stole one election too many in 1910, indigenous villagers in Morelos state chose one of their own, a horse trainer named Emiliano Zapata, to lead them in revolt.

The EZLN namesake was an anarchist land reformer whose armies controlled one third of Mexico in 1914. Zapata's initial platform, the San Luis Potosí Plan, called for the restoration of lands stolen from peasants under the dictatorship, with those who took the land paying compensation for the losses they caused. This was especially popular in Morelos, where indigenous people lost their subsistence farms to make way for huge sugar plantations. As the revolution heated up, Zapata's Ayala Plan called for the rich to give up a further one-third of their possessions for distribution to the poor. While Zapata's ally Pancho Villa sought and briefly held command of the Mexican army, Zapata wanted to abolish the standing army. Zapata carried out his plans in Morelos and neighboring states, but on April 10, 1919 the government lured the rebel leader to a meeting and murdered him.

The Chiapas crisis comes in an election year, when all appearances are that the PRI will need yet another fraudulent vote count to hold onto power. President Carlos Salinas de Gortari holds office due to a 1988 election fraud against Cuauhtemoc Cárdenas of the leftist Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD). In August elections, Cárdenas will challenge Salinas' hand-picked successor for a year term as president. Since the last presidential vote, frauds in state elections sometimes caused riots and occupations of government buildings. [Phillis Engelbert and Jeff Gearhart covered the aftermath of the last stolen federal election in November 1988's AGENDA.] With a peasant army already in the field, many observers draw comparisons to 1910, and wonder aloud if another election theft could spark a civil war.

To head off that possibility, the PRI announced an agreement on election reforms. Instead of the old PRI election supervisors, an independent election commission will be appointed. Government financial support forthe PRI's campaign will be withdrawn. Radio and TV stations will no longer be exclusive PRI propaganda outlets. There will be an independent prosecutor to review any election theft charges. Despite his acceptance of the agreement, PRD leader Cárdenas immediately expressed doubts that the ruling party would live up to it. Other PRD spokespeople attributed the agreement to pressures generated by the Chiapas uprising.

The EZLN has no ties with any political party, and denies any "perfectly-defined deology," such as Marxsm-Leninism. Comandante Marcos downplays his group's differences with the PRD: "We don't distrust the political parties as much as we do the electoral system. The government of Salinas de Gortari is an Ilegitimate product of fraud, and this Ilegitimate government can only produce Iegitimate elections."

The Zs call for the PRI govemment's overthrow, the formation of a transitional regime and new, fair elections. "Based on that," said Comandante Marcos, "other demands can be negotiated: bread, housing, health, education, land, justice, many problems which, within the context of indigenous people, are very serious. But the demands for liberty and democracy are being made as a call to all the Mexican Republic, to all the social sectors."

The EZLN calls for redistribution of the land and the cancellation of debts owed by peasants. A paper that the Zs distributed during the offensive advocated equality for women, urban reforms, labor rights and corruption trials for politicians. lt announced war taxes to be collected from landowners and business people in rebel-held areas.

The possibility of war taxes - rebel or government - diminished hopes that NAFTA could rescue Mexico and its ruling elite from social and economic pressures that have been building for years. The expected January flood of foreign investment was just a trickle. Few U.S. and Canadian factory owners seem eager to run away to Latin America's newest war zone and pay taxes to a rebel army. Chiapaneco peasants don't seem to be in the mood to buy many U.S. -made consumer goods. Suddenly, NAFTA doesn't look like much of a vote-getter for the PRI. If the main damage inflicted by the Zapatistas is the smashing of illusions which the PRI carefully nurtured, that might be just enough to bring down the government.

Those who are interested in promoting human rights and social progress in Mexico and elsewhere in Latin America should consider joining the Latin American Solidarity Committee (LASC). LASC now meets every Thursday night at 8 pm in the Michigan Union. Check the information desk or the LASC office at room 4120 for the meeting room.