Rhythms Of Life

Rhythms of Life

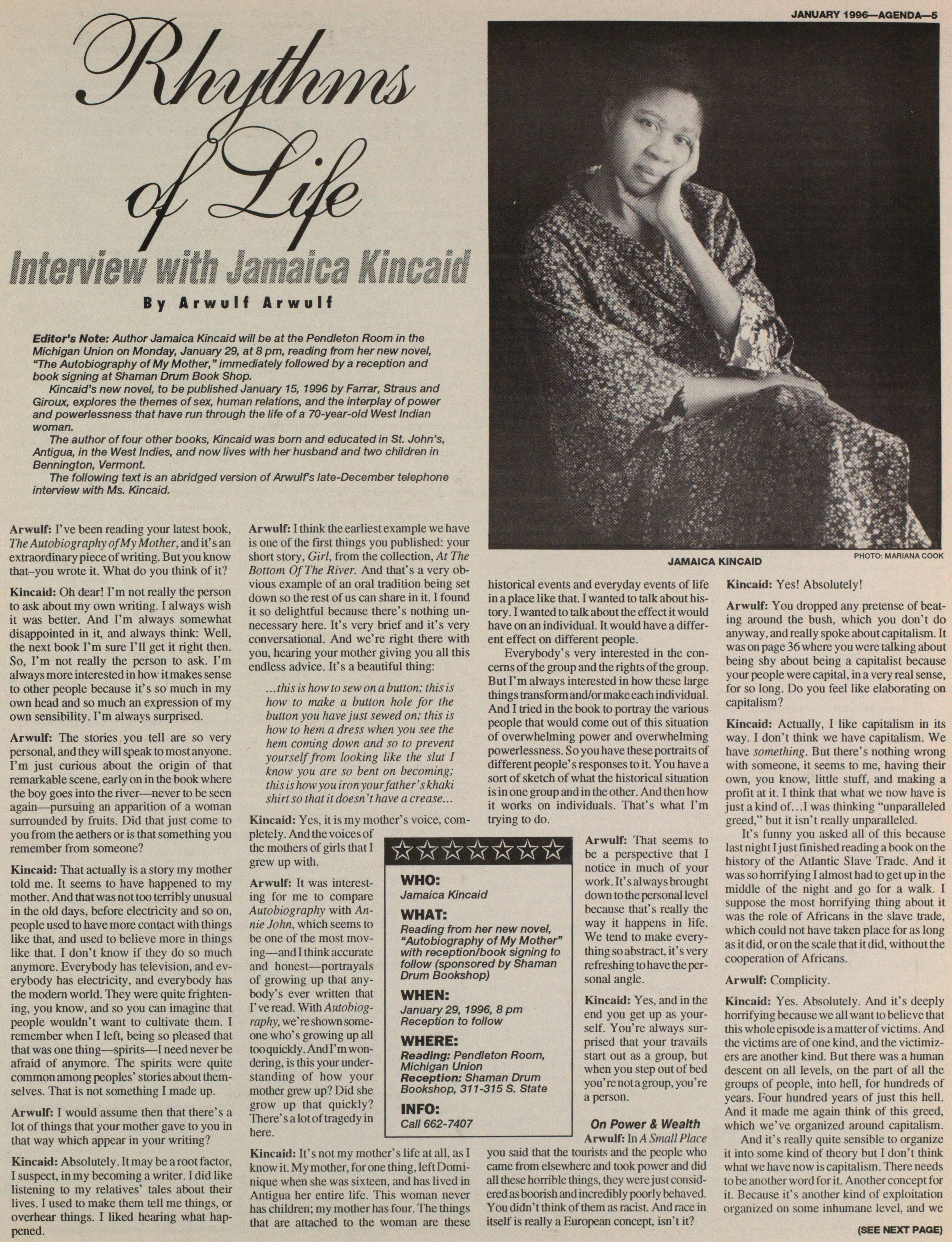

Interview with Jamaica Kincaid

by Arwulf Arwulf

Editor's Note: Author Jamaica Kincaid will be at the Pendleton Room in the Michigan Union on Monday, January 29, at 8pm, reading from her new novel, "The Autobiography of My Mother," immediately followed by a reception and book signing at Shaman Drum Book Shop.

Kincaid's new novel, to be published January 15, 1996 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, explores the themes of sex, human relations, and the interplay of power and powerlessness that have run through the life of a 70-year-old West Indian woman.

The author of four other books, Kincaid was born and educated in St. John's, Antigua, in the West Indies, and now lives with her husband and two children in Bennington, Vermont.

The following text is an abridged version of Arwulfs late-December telephone interview with Ms. Kincaid.

Arwulf: I've been reading your latest book, The Autobiography of My Mother, and it's an extraordinary piece of writing. But you know that-you wrote it. What do you think of it?

Kincaid: Oh dear! I'm not really the person to ask about my own writing. I always wish it was better. And I'm always somewhat disappointed in it, and always think: Well, the next book I'm sure I'll get it right then. So, I'm not really the person to ask. I'm always more interested in how it makes sense to other people because it's so much in my own head and so much an expression of my own sensibility. I'm always surprised.

Arwulf: The stories you tell are so very personal, and they will speak to most anyone. I'm just curious about the origin of that remarkable scene, early on in the book where the boy goes into the river - never to be seen again - pursuing an apparition of a woman surrounded by fruits. Did that just come to you from the aethers or is that something you remember from someone?

Kincaid: That actually is a story my mother told me. It seems to have happened to my mother. And that was not too terribly unusual in the old days, before electricity and so on, people used to have more contact with things like that, and used to believe more in things like that. I don't know if they do so much anymore. Everybody has television, and everybody has electricity, and everybody has the modern world. They were quite frightening, you know, and so you can imagine that people wouldn't want to cultivate them. I remember when I left, being so pleased that that was one thing - spirits - I need never be afraid of anymore. The spirits were quite common among peoples' stories about themselves. That is not something I made up.

Arwulf: I would assume then that there's a lot of things that your mother gave to you in that way which appear in your writing?

Kincaid: Absolutely. It may be a root factor, I suspect, in my becoming a writer. I did like listening to my relatives' tales about their lives. I used to make them tell me things, or overhear things. I liked hearing what happened.

Arwulf: I think the earliest example we have is one of the first things you published: your short story, Girl, from the collection, At The Bottom Of The River. And that's a very obvious example of an oral tradition being set down so the rest of us can share in it. I found it so delightful because there's nothing unnecessary here. It's very brief and it's very conversational. And we're right there with you, hearing your mother giving you all this endless advice. It's a beautiful thing:

. . . this is how to sew on a button; this is how to make a button hole for the button you have just sewed on; this is how to hem a dress when you see the hem coming down and so to prevent yourself from looking like the slut I know you are so bent on becoming; this is how you iron your father's khaki shirt so that it doesn't have a crease. . .

Kincaid: Yes, it is my mother's voice, completely. And the voices of the mothers of girls that I grew up with.

Arwulf: It was interesting for me to compare Autobiography with Annie John, which seems to be one of the most moving - and I think accurate and honest - portrayals of growing up that anybody's ever written that I've read. With Autobiography, we're shown someone who's growing up all too quickly. And l'm wondering, is this your understanding of how your mother grew up? Did she grow up that quickly? There's a lot of tragedy in here.

Kincaid: It's not my mother's life at all, as I know it. My mother, for one thing, left Dominique when she was sixteen, and has lived in Antigua her entire life. This woman never has children; my mother has four. The things that are attached to the woman are these historical events and everyday events of life in a place like that. I wanted to talk about history. I wanted to talk about the effect it would have on an individual. It would have a different effect on different people.

Everybody's very interested in the concerns of the group and the rights of the group. But I'm always interested in how these large things transform and/or make each individual. And I tried in the book to portray the various people that would come out of this situation of overwhelming power and overwhelming powerlessness. So you have these portraits of different people' s responses to it. You have a sort of sketch of what the historical situation is in one group and in the other. And then how it works on individuals. That's what I'm trying to do.

Arwulf: That seems to be a perspective that I notice in much of your work. It's always brought down to the personal level because that's really the way it happens in life. We tend to make everything so abstract, it's very refreshing to have the personal angle.

Kincaid: Yes, and in the end you get up as yourself. You're always surprised that your travails start out as a group, but when you step out of bed you're not a group, you're a person.

On Power & Wealth

Arwulf: In A Small Place you said that the tourists and the people who came from elsewhere and took power and did all these horrible things, they were just considered as boorish and incredibly poorly behaved. You didn't think of them as racist. And race in itself is really a European concept, isn't it?

Kincaid: Yes! Absolutely!

Arwulf: You dropped any pretense of beating around the bush, which you don't do anyway, and really spoke about capitalism. It was on page 36 where you were talking about being shy about being a capitalist because your people were capital, in a very real sense, for so long. Do you feel like elaborating on capitalism?

Kincaid: Actually, I like capitalism in its way. I don't think we have capitalism. We have something. But there's nothing wrong with someone, it seems to me, having their own, you know, little stuff, and making a profit at it. I think that what we now have is just a kind of. . .I was thinking "unparalleled greed," but it isn't really unparalleled.

It's funny you asked all of this because last night I just finished reading a book on the history of the Atlantic Slave Trade. And it was so horrifying I almost had to get up in the middle of the night and go for a walk. I suppose the most horrifying thing about it was the role of Africans in the slave trade, which could not have taken place for as long as it did, or on the scale that it did, without the cooperation of Africans.

Arwulf: Complicity.

Kincaid: Yes. Absolutely. And it's deeply horrifying because we all want to believe that this whole episode is a matter of victims. And the victims are of one kind, and the victimizers are another kind. But there was a human descent on all levels, on the part of all the groups of people, into hell, for hundreds of years. Four hundred years of just this hell. And it made me again think of this greed, which we've organized around capitalism.

And it's really quite sensible to organize it into some kind of theory but I don't think what we have now is capitalism. There needs to be another word for it. Another concept for it. Because it's another kind of exploitation organized on some inhumane level, and we

(SEE NEXT PAGE)

WHO:

Jamaica Kincaid

WHAT: Reading from her new novel, "Autobiography of My Mother" with reception/book signing to follow (sponsored by Shaman Drum Bookshop)

WHEN: January 29, 1996, 8 pm Reception to follow

WHERE: Reading: Pendleton Room, Michigan Union Reception: Shaman Drum Bookshop, 311-315 S. State

INFO: Call 662-7407

(FROM PREVIOUS PAGE) need to be able to identify it and to deal with it imaginatively.

You know it's so involved. It holds so much pain, so much cruelty, so much murder, on the part of a small group of people, and again complicity. On all our parts. And again the senseless accumulation of wealth. No one, no one has ever been able to say what to do with all of this wealth that one has. You can't do anything with it. And if it represents power, there's a limit to what you can do with this power. The only pleasure you can get out of this power is the pleasure of just seeing people tossed around. That hardly seems pleasure to me.

Arwulf: It's interesting that you should say that we don't really have capitalism. It's like, who has ever really done socialism, either? Maybe when we put names on things like that, then they get distorted and people oversimplify.

Kincaid: I do think that these things must be communally and democratically decided on. Though one can't say that what we have has been communally and democratically decided on at all. I suppose you and I could talk about it forever and we'd just come to this incredible grief. But there is something enormously wrong. I say this sitting quite comfortably in a nice room in Vermont. And I'm sure there's somebody somewhere who's paid for my little comfort. I'm very aware that it's quite possible that what I have, even though I don't have very much at all - it's a very modest room, and I am always, as most people in my situation, in enormous debt - I'm always aware that perhaps for every little comfort I have, maybe someone has less. And I insist on being reminded of that, actually.

Arwulf: You have a very highly developed sense of that, which I admire.

Kincaid: Well, I come from the opposite of it and I feel obligated to always remember that. My life is very peculiar because there's no reason in the world for you and I to be speaking to each other; there's no reason in the world that I should have had the opportunity to have written books and to have people interested in them. And I've never really quite lost the interest in the mystery of how that came to be.

On Racism & Greed

Arwulf: There is a chapter in Autobiography which begins:

What makes the world turn? Who would need an answer to such a question? A man proud of the pale hue of his skin cherishes it especially because it is not a fulfillment of any aspiration, it is his not through any effort at all on his part; he was just born that way, he was blessed and chosen to be that way and it gives him a special privilege in the hierarchy of everything. This man sits on a plateau, not on the level ground, and all he can see...he knows with an iron certainty should be his own.

What makes the world turn is a question he asks when all that he can see is...so securely in his grasp that he can cease to look at it from time to time, he can denounce it, he can demand that it be taken away from him, he can curse the moment he was conceived and the day he was born, he can go to sleep at night and in the morning he will wake up and all he can see is still securely in his grasp; and he can ask again, What makes the world turn, and then he will have an answer and it will take up volumes and there are many answers, each of them different, and there are many men, each of them the same.

And what do I ask? What is the question I can ask? I own nothing, I am not a man.

It seemed like the heart of the book's message for me - one of the most resounding passages - where you give a great depiction of the mindset of a person who would come along and need to measure everything, and need to own everything.

Kincaid: I think of that as the most tricky part for the reader. I'm so glad that you noticed that and that it didn't throw you. I really wanted to say those things in it and I thought it was perhaps abstract for people. . .

Arwulf: Oh, anything but! It noticed me. I've been walking around blinking ever since I read that. Because it was, again, so beautifully put. It needed to be said and you said it so well.

Kincaid: I'm very deeply pleased and touched that you said that because when I was editing, correcting it, and I came to that part I really thought 'well this is where I'll lose the reader but so be it.' So I'm very glad that you got that.

Fabric as History

Arwulf: Do you foresee a continuing series of portrayals of women from your background?

Kincaid: I imagine so. As long as I'm alive I'll always be interested in this area of my own; I can only write autobiographical things, in the sense that l can only write not just about my own individual life, but about the life of the people I know. I can only try to sort it out: What happened? Why did it happen? Who did it happen to?

Arwulf: On the cover of Autobiography there is a photograph of what appears to be a young West-Indian woman. Is this a picture of your mother?

Kincaid: No. It's a postcard that was given to me on my 25th birthday. On the back of it it says 'Happy 25th Birthday!' It was such a beautiful postcard, I kept it. And I've had it all these years. I was 25 in 1974.

Arwulf: I'm so presumptuous. I'm sure everybody presumes all these things.

Kincaid: Yes. But my mother wouldn't have been that age. That postcard is from 1934. And it's of a woman in native dress from Martinique. They remained French. Dominique changed hands; Dominique was French and became English, but it kept a lot of its French influence. So it's not out of context at all. Dominiquans did still have that sort of head dress. And the thing about that kind of costume, it has many things in it from parts of the conquests of Britain. It has cotton, madras - all the materials that she's wearing are the products of colonial empire, or slavery. Fascinating, eh?

Arwulf: Now that you mention it, yes. I'm never going to look at that picture in quite the casual way that I did before...

Kincaid: Yes, it's very interesting about people from my background. We always identify fabric. So that you say 'madras,' 'nankeen,' 'sea island cotton,' you call the fabric by its name. 'Seersucker.' You always say 'dotted Swiss' or whatever it is, you always call it. And for a long time I was just very interested in that, and I realized that in a way, when you are identifying the fabric you are really talking historically, you are saying enormous volumes of things, just by the word.

For instance, poplin is a weave that Huguenot French people brought with them to England when they were being persecuted, and it was a weave of fabric for a Pope's clothes; poplin. We would always say a 'poplin' or a 'linen.' And I realized that we were just saying 'history.' We're just speaking history.

If you look at a piece of poplin, I don't know if they use that weave any more, it was kind of coarse, and it had a certain kind of bounce to it. But in any case it was always interesting to me that we would always identify the cloth. Cloth and weave, I think, always has incredible history to it, and a lot of it is oppressive. Or horrifying.

Arwulf: It represents labor.

Kincaid: It represents labor, which ought to be an expression of the deepest being, a kind of spiritual expression. Through work you know yourself; it's often associated really with a blunting of the self.

A Geometry of Style

Arwulf: The first thing that I noticed when reading your books was that you seem to write about things from so many different angles. In fact you even said so. For example, in Annie John, when she went to the grocer's with her mother - I think the exact quote was: 'I was shown a loaf of bread or a pound of butter from at least ten different angles.' It seemed like a perfect description of your style. Has anyone else pointed that out?

Kincaid: I don't think anyone has ever said that. It's interesting because in that case, she was, I believe, complaining about the thoroughness of this process of being acculturated into that particular kind of femaleness. And she was being sort of cynical about it. How can one loaf of bread be so interesting? Or how can anything so common be so interesting when there was a whole world of historical difficulties, a whole world of all sorts of difficulties? I think that was what she was saying.

But I see what you mean. And I have to say I think you're right. One of the things that I suspect people like me, from my part of the world, or with my history, would have to do would be to look at the world from the angles that haven' t been looked at before. Not because of deliberately wanting to be new but just because that is our reality, and it has not been looked at before, for all sorts of reasons. Many many reasons. But there are many people like me, presenting the world, the same world, but from many different angles.

Arwulf: From a very personal angle and then also from the perspective of a people who have not had a voice, officially.

Kincaid: Yes. I would put it even more indecently. I would say, the voice of the defeated.

Small Places

Arwulf: A Small Place is the most refreshingly direct and no-nonsense statement that I've ever found on the subject of colonialism and neo-colonialism. It would be helpful if everybody in North America would own a copy and read it. There's not one wasted syllable in here. You deliver it all in a remarkably short space, and you say so much that needs to be said. And it's very humbling. I know that North Americans and Europeans are not fond of being humbled. I think that's something we have to re-learn.

Kincaid: Yes, true. I suppose when one wins, it's hard to take time to sort it out. Winning is delicious.

Arwulf: But then we must figure out what constitutes winning. It's wickedly overemphasized. Here in the University of Michigan community I keep hearing this phrase 'We're Number One' and it just gives me hives! I mean that's a storm trooper term.

Kincaid: Yes! Oh boy, it sounds awful. Why you'd want to be that. It's hard to fathom.

Arwulf: But they teach young people to say that here. Loudly.

Kincaid: Yes, they're number one in which case I'd always want to be number two, three or somewhere below that.

Arwulf: What is so frightening about number one from your perspective?

Kincaid: Well, the moment one isn't, would be my first fear. There's always a moment when one isn't. And it's such an overwhelming fear, such a profound fear that you do all sorts of things to maintain number one, and none of them will ever be good. Because the natural flow of things is that it goes up it goes down, it goes down it goes up, and if you are grasping to be, and your whole psychological being depends on your being this number one, you know you're bound to be anxious that you won't be, and then the anxiety will lead to just incredible unhappiness. You never get to even enjoy being number one anyway. Unless you're truly remarkable and you just get to be number one and say 'ah!' and expire.

There's great anxiety in this country that we' re not number one anymore, that there isn't anyone clearly who' s number one. So you can still be under the illusion that we're number one, but they're even writing that we're not. So I feel your school mirrors a larger continental problem. Or national problem.

Arwulf: And of course most of the people who can afford to go here are from some very privileged sectors of life population, and so the whole perspective is very distorted. It's very frightening to operate in this community - to work here, to watch people carrying on. How are things in Vermont?

Kincaid: Vermont somehow seems to be immune, still, from all sorts of things. The collective consciousness about Vermont is that it should remain Vermont. It's still rural and still fine. It doesn't have so many of these anxieties. We get to Vermont and the general calm of Vermont overtakes us and so we lose all that. It just remains a kind of a nice place. It's very beautiful and unhurried and uninterested in becoming the Aspen of the North, or the anything of the anything. It's just Vermont. It's as if it has gotten the special grace of always being never fashionable.

Arwulf: Well I hope that endures.

Kincaid: I hope so too! I mean this is America. But there's something about it. It doesn't seem fashionable to people. It sort of resist trends, really.

Arwulf: We have this horrible word: 'development.' And then there's the converse: 'underdeveloped.' But Vermont doesn't seem to fit into either category, does it?

Kincaid: No! It's too many cows, I think.

Arwulf: Cows and hills!

Kincaid: And the soil is very full of rocks. Yes it resists these things. I think. But maybe I'd better not speak too soon. I'd better knock my head. For wood.

AGENDA wishes to acknowledge the generous assistance of Thomas Bray, and thank him tor recording this interview at the WCBN-FM production studio.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Autobiography of My Mother

(Fiction) Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1996 (226p)

Lucy (Fiction) Plume, 1990 (164p)

A Small Place (Non-Fiction) Plume, 1988 (81p)

Annie John (Fiction) Plume, 1985 (148p)

At The Bottom of the River (Fiction-Short Stories) Plume, 1978 (82p)