Race & Education In A2 Public Schools Confronting The Blackwhite Test-score Gap An Interview With "achievement Initiative" Cheif, Blanche D. Pringle

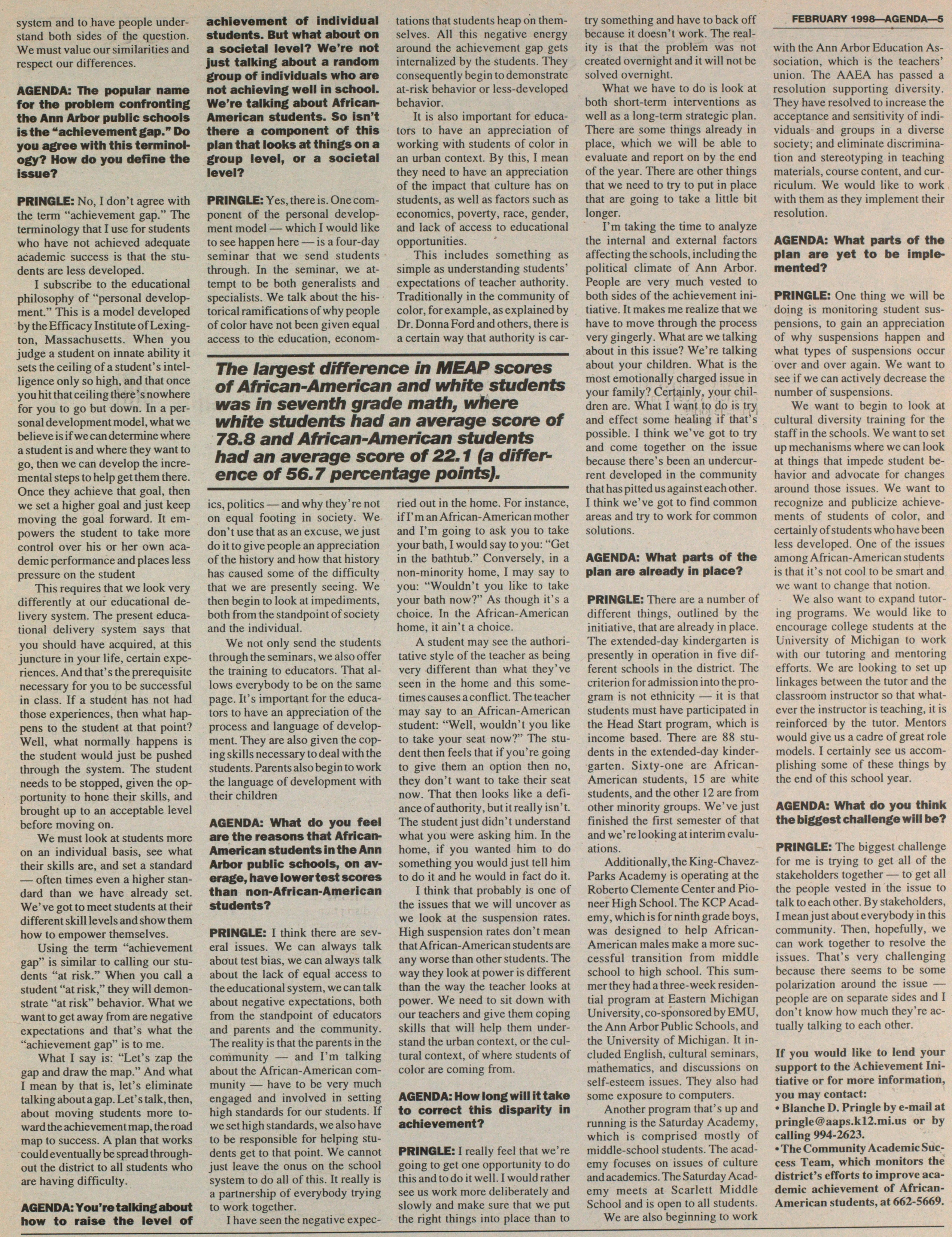

For the last several months, the words "achievement gap" have been resonating through the streets, schools, and cafes of AnnArbor. However, the discrepancy that exists between the academie achievement of African-American and white students in the Ann Arbor public schools is nothing new. The so-called achievement gap has been of concern for years. In 1 99 1 , in response to the widening gulf between African-American and white students' scores on standardized tests, the Ann Arbor School Board set a goal of eliminating the achievement gap by the year 2000. To that end, they implemented a modest program aimed to boost the achievement of AfricanAmerican students. Five years later, when the results of the l%-97 MEAP were reported, it became clear that those gap-closing efforts were not working. (MEAP, which stands for Michigan Education Assessment Program, is a standardized test given to students in fourth and seventh grades throughout the state of Michigan.) In the 1996-97 MEAP, African-American students in Ann Arbor - who make up 1 7 percent of the student population - scored sign ificantly lower than their white counterparts. The largest difference in MEAP scores of African-American and white students was in seventh grade math, where white students had an average score of 78.8 and AfricanAmerican students had an average score of 22. 1 (a difference of 56.7 percentage points). The smallest difference was in seventh grade reading, where white students had an average score of 65.5 and African-American students had an average score of 28.0 (a difference of 37.5 percentage points). The gap between the AfricanAmerican and white student MEAP scores had actually grown larger than it was in 1 99 1 . The increase in the gap ranged from 2.8 percentage points in fourth grade reading to 8.6 percentage points in seventh grade math. In addition, AfricanAmerican students in Ann Arbor had for the first time scored below statewide averages for AfricanAmerican students in three out of four categories. The MEAP results - coupled with the finding that AfricanAmerican students were being suspended from class at five times the rate of white students - outraged many in the community and jolted the school board into action. Relying on input from parents, teachers, "and community leaders, the board carne up with an aggressive new plan to "close the gap." In June 1997, the nine-member school board unanimously approved the Achievement Initiative - an eleven-step plan to boost the academie performance of AfricanAmerican students. They allocated $460,000 to implement the plan, the components of which are: Hire an administrator to oversee the plan. Identify obstacles to AfricanAmerican student achievement. Establish full-day kindergarten classes at six elementary schools for former pupils of the district's pre-school program. Expand tutoring and mentoring programs for African-American students. Begin a parent support group that encourages parents to become more involved in theirchildren's education. Provide cultural diversity training for school staff. Recognize and publicize academie achievements of African-American students. Develop a system to track and reduce student suspensions. Develop skill-building support programs for elementary school students. Involve the teachers' union in efforts to close the gap. Solicit concerns and suggestions from students and parents. The school board 's plan has not been without its critics. On Sept. 29, 1997, Ann Arbor resident and former industrial engineer Jack Rice filed a complaint against the plan with U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno. Rice claimed that the plan is racist because it does not provide assistance for can-American students and that the school board is "usurping the civil rights" of non-African-American students. In mid-December, the U.S. Department of Education announced that it would investígate the complaint and that it expected the investigation to take four months. Rice's complaint, which was co-signed by a handful of other, unnamed Ann Arbor residents, evoked a vigorous response from Ann Arbor School officials. "The vast majority of our $126 million budget is spent on behalf of all children," stated Deputy Superintendent David Flowers in the Oct. 24, 1997, Ann Arbor News. "We've setasidea very small pot of money for a group of students that the data show are not reaching their potential in disproportionate numbers." District superintendent John Simpson added the following comment in the Dec. 17, 1997, Ann Arbor News: "We' ve said all along that it was our intention to learn from these initiatives and then expand the ones that work to help all students in need." In October 1997, the school board fulfilled one of the plan's mandates by hiring Blanche D. Pringle to oversee the Achievement Initiative. Pringle began work as Administrative Liaison for the Achievement Initiative on December 1. Before coming to the Ann Arbor schools, Pringle was Director of Minority Affairs and Outreach Programs at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) in Massachusetts. In that capacity, she oversaw the recruitment and retention of students of color. When Pringle started that position in 1993, there were 16 students of color at WPI. By the time she left, the number had risen to over 120, with a 90 percent retention rate. Prior to that, Pringle worked at Freedom House - a communitybased agency in Roxbury, Massachusetts - as the director of Project Reach. Project Reach is a program that provides college students of color with academie counseling, financial assistance, and other types of support. During Pringle's tenure, there was a 92 percent retention rate of the 300 students in the program, who were attending 89 colleges throughout the United States. Pringle has also worked as a lobbyist for Wayne State University and as director of education for the Detroit Urban League. She holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in painting and design from Bowling Green State University in Ohio. She completed one year of Iaw school at Valparaíso University in Indiana. The following text is from a January, 1 998, interview conducted with B lanche Pringle by AGENDA staffer Phillis Engelbert. AGENDA: Why is it in the interest of non-African Americans to elimínate the achievement gap? BLANCHE D. PRINGLE: If there is disruption or there is not a climate conducive to learning in the classroom, that's going to affect students who are high achievers and students who are low achievers. If a teacher is spending an inordinate amount of time in class going over material, having to provide remedial skill-building, then those students who are on the higher fringe are really not as engaged in the educational process as they could be. And they ' re not gi ven the opportunity to learn more. What we've got to do is make sure the learning environment is positive for all students to learn more. AGENDA: The school board has allocated $460,000 to fund this plan. What do you say to people who claim that the plan discriminates against non-minority dents or who are, for other reasons, against the plan? PRINGLE: Really, that's a very hard thing to get people to understand because the reality is it's a very, very small amount of money . The other thing is, the activities that are already in place are not exclusively for students of color. We' ve got to get the word out that this is the case. My hope is that we can use the group of students of color to try field trials and test initiatives and see what works. We can then develop a model that can be used for all students. The lessons that we learn do not have any particular color on them, they're just good things for all students. AGENDA: In a December 17 editorial, The Ann Arbor News claimed that your remarks regarding critics of the initiative were "dialogue-stopping." They inferred that you consider critics of the plan to be racist or bigoted and that such attitudes will keep the plan "mired in controversy." What is your response to that editorial? PRINGLE: My belief is "ït [the editorial] is not the stimulus, it is the response." Reacting to the editorial would move me away from my purpose here, which is to develop a comprehensive plan to improve student achievement. What I will say is that I think that we - on both sides of the issue - have to search our hearts. We must see if there is some consensus around which we can work. Yes, we have to have a dialogue in terms of ethnicity and race within the system and to have people understand both sides of the question. We must value our similarities and respect our differences. AGENDA: The popular name for the problem confronting the Ann Arbor public schools is the "achievement gap." Do you agree with this terminology? How do you define the issue? PRINGUE: No, I don't agree with the term "achievement gap." The terminology that I use for students who have not achieved adequate academie success is that the students are less developed. I subscribe to the educational philosophy of "personal development." This is a model developed by the Efficacy Institute of Lexington, Massachusetts. When you judge a student on innate ability it sets the ceiling of a student' s intelligence only so high, and that once you hit that ceiling there' s nowhere for you to go but down. In a personal development model, what we believe is if we can determine where a student is and where they want to go, then we can develop the incremental steps to help get them there. Once they achieve that goal, then we set a higher goal and just keep moving the goal forward. It empowers the student to take more control over his or her own academie performance and places less pressure on the student This requires that we look very differently at our educational de1 i very system. The present educational delivery system says that you should have acquired, at this juncture in your Ufe, certain experiences. And that' s the prerequisite necessary for you to be successful in class. If a student has not had those experiences, then what happens to the student at that point? Well, what normally happens is the student would just be pushed through the system. The student needs to be stopped, given the opportunity to hone their skills, and brought up to an acceptable level before moving on. We must look at students more on an individual basis, see what their skills are, and set a standard - often times even a higher standard than we have already set. We' ve got to meet students at their different skill levéis and show them how to empower themselves. Using the term "achievement gap" is similar to calling our students "at risk." When you cali a student "at risk," they will demónstrate "at risk" behavior. What we want to get away from are negati ve expectations and that's what the "achievement gap" is to me. What I say is: "Let's zap the gap and draw the map." And what I mean by that is, let's elimínate talkingaboutagap. Let's talk, then, about moving students more toward the achievement map, the road map to success. A plan that works could eventually be spread throughout the district to all students who are having difficulty. AGENDA: You 're talking about how to raise the level of achievement of individual students. But what about on a societal level? We're not just talking about a random group of individuals who are not achieving well in school. We're talking about AfricanAmerican students. So isn't there a component of this plan that looks at things on a group level, or a societal level? PRINGLE: Yes, there is. One component of the personal development model - which I would like to see happen here - is a four-day seminar that we send students through. In the seminar, we attempt to be both generalists and specialists. We talk about the historical ramifications of why people of color have not been given equal access to the education, ics, politics - and why they ' re not on equal footing in society. We don 't use that as an excuse, we just do it to gi ve people an appreciation of the history and how that history has caused some of the difficulty that we are presently seeing. We then begin to look at impediments, both from the standpoint of society and the individual. We not only send the students through the seminars, we also offer the training to educators. That allows everybody to be on the same page. It's important for the educators to have an appreciation of the process and language of development. They are also given the coping skills necessary to deal with the students. Parents also begin to work the language of development with their children AGENDA: What do you feel are the reasons that Af ricanAmerican students in the Ann Arbor public schools, on average, have lower test scores than non-African-American students? PRINGLE: I think there are several issues. We can always talk about test bias, we can always talk about the lack of equal access to the educational system, we can talk about negative expectations, both from the standpoint of educators and parents and the community. The reality is that the parents in the community - and I'm talking about the African-American community - have to be very much engaged and involved in setting high standards for our students. If we set high standards, we also have to be responsible for helping students get to that point. We cannot just leave the onus on the school system to do all of this. It really is a partnership of everybody trying to work together. I have seen the negative tations that students heap on themselves. All this negative energy around the achievement gap gets internalized by the students. They consequently begin to demónstrate at-risk behavior or less-developed behavior. It is also important for educators to have an appreciation of working with students of color in an urban context. By this, I mean they need to have an appreciation of the impact that culture has on students, as well as factors such as economics, poverty, race, gender, and lack of access to educational opportunities. This includes something as simple as understanding students' expectations of teacher authority. Traditionally in the community of color, for example, as explained by Dr. Donna Ford and others, there is a certain way that authority is ried out in the home. For instance, if I'm an American mother and I'm going to ask you to take your bath, I would say to you: "Get in the bathtub." Conversely, in a non-minority home, I may say to you: "Wouldn't you like to take your bath now?" As though it's a choice. In the African-American home, it ain't a choice. A student may see the authoritative style of the teacher as being very different than what they've seen in the home and this sometimes causes a conflict. The teacher may say to an African-American student: "Well, wouldn't you like to take your seat now?" The student then feels that if you're going to give them an option then no, they don't want to take their seat now. That then looks like a defiance of authority , but it really isn' t. The student just didn't understand what you were asking him. In the home, if you wanted him to do something you would just teil him to do it and he would in fact do it. I think that probably is one of the issues that we will uncover as we look at the suspension rates. High suspension rates don't mean that African-American students are any worse than other students. The way they look at power is different than the way the teacher looks at power. We need to sit down with our teachers and give them coping skills that will help them understand the urban context, or the cultural context, of where students of color are coming from. AGENDA: How long will it take to correct this disparity in achievement? PRINGLE: I really feel that we're going to get one opportunity to do this and to do it well. I would rather see us work more deliberately and slowly and make sure that we put the right things into place than to try something and have to back off because it doesn't work. The reality is that the problem was not created overnight and it will not be solved overnight. What we have to do is look at both short-term interventions as well as a long-term strategie plan. There are some things already in place, which we will be able to evalúate and report on by the end of the year. There are other things that we need to try to put in place that are going to take a little bit longer. I'm taking the time to analyze the internal and external factors affecting the schools, including the political climate of Ann Arbor. People are very much vested to both sides of the achievement initiative. It makes me realize that we have to move through the process very gingerly. What are we talking about in this issue? We're talking about your children. What is the most emotionally charged issue in your family? Certainly, your children are. What I want to do is try and effect some healing if that's possible. I think we've got to try and come together on the issue because there's been an undercurrent developed in the community that has pitted us against each other. I think we've got to find common areas and try to work for common solutions. AGENDA: What parts of the plan are already in place? PRINGLE: There are a number of different things, outlined by the initiative, that are already in place. The extended-day kindergarten is presently in operation in five different schools in the district. The criterion for admission into the program is not ethnicity - it is that students must have participated in the Head Start program, which is income based. There are 88 students in the extended-day kindergarten. Sixty-one are AfricanAmerican students, 15 are white students, and the other 1 2 are from other minority groups. We've just finished the first semester of that and we're looking at interim evaluations. Additionally , the King-ChavezParks Academy is operating at the Roberto Clemente Center and Pioneer High School. The KCP Academy, which is for ninth grade boys, was designed to help AfricanAmerican males make a more successful transition from middle school to high school. This summer they had a week residential program at Eastern Michigan University , co-sponsored by EMU, the Ann Arbor Public Schools, and the University of Michigan. It included English, cultural seminars, mathematics, and discussions on self-esteem issues. They also had some exposure to computers. Another program that's up and running is the Saturday Academy, which is comprised mostly of middle-school students. The academy focuses on issues of culture and academies. The Saturday Academy meets at Scarlett Middle School and is open to all students. We are also beginning to work with the Ann Arbor Education Association, which is the teachers' unión. The AAEA has passed a resolution supporting diversity. They have resolved to increase the acceptance and serrsitivity of individuals and groups in a diverse society; and eliminate discrimination and stereotyping in teaching materials, course content, and curriculum. We would like to work with them as they implement their resolution. AGENDA: What paris of the plan are yet to be implement ed? PRINGLE: One thing we will be doing is monitoring student suspensions, to gain an appreciation of why suspensions happen and what types of suspensions occur over and over again. We want to see if we can actively decrease the number of suspensions. We want to begin to look at cultural diversity training for the staff in the schools. We want to set up mechanisms where we can look at things that impede student behavior and advocate for changes around those issues. We want to recognize and publicize achievements of students of color, and certainly of students who have been less developed. One of the issues among American students is that it's not cool to be smart and we want to change that notion. We also want to expand tutoring programs. We would like to encourage college students at the University of Michigan to work with our tutoring and mentoring efforts. We are looking to set up linkages between the tutor and the classroom instructor so that whatever the instructor is teaching, it is reinforced by the tutor. Mentors would give us a cadre of great role models. I certainly see us accomplishing some of these things by the end of this school year. AGENDA: What do you think the biggest challenge will be? PRINGLE: The biggest challenge for me is trying to get all of the stakeholders together - to get all the people vested in the issue to talk to each other. By stakeholders, I mean just about everybody in this community. Then, hopefully, we can work together to resolve the issues. That's very challenging because there seems to be some polarization around the issue - people are on separate sides and I don't know how much they're actually talking to each other. If you would like to lend your support to the Achievement Initiative or for more information, you may contact: Blanche D. Pringle by e-mail at pringle@aaps.kl2.mi.us or by calling 994-2623. The Community Academie Success Team, which monitors the district's efforts to improve academie achievement of AfricanAmerican students, at 662-5669. The largest difference in MEAP scores of Afhcan-American and white students was in seventh grade math, where white students had an average score of 78.8 and African-Amehcan students had an average score of 22. 1 (a difference of 56.7 percentage points).