Global Warming: You're In The Driver's Seat

EDITOR' S NOTE: Jeff Alson is a Senior Policy Analyst for the U.S. Environment al Protection Agency and is a national expert on transportation and climate issues. The views in this article are his own and do not necessarily represent those of the EPA.

Forget El Niño. Sure, it has been the primary cause of a lot of disruptive weather and human suffering this winter. But El Niño will come and go, and its consequences are fairly predictable. Most important, there is nothing that we can do about it.

All the attention to El Niño is obscuring the much more important weather story: Global Warming. Most scientists now agree that the atmospheric buildup of carbon and other pollution threatens to seriously disrupt the world's climate and represents the greatest single global environmental threat of the new millennium. Global warming could be like having El Niños everywhere, every day.

Unlike El Niño, you can do something about global warming. While we can blame the dinosaurs for the carbon in the ground, it is people like us who are responsible for spewing it into the atmosphere. And we Americans create far more carbon pollution than any other country on earth.

While none of us can unilaterally stop global warming, we must begin to take personal responsibility for our actions. The most effecti ve steps most of us can take to reduce the threat of global warming are to buy vehicles with higher miles per gallon ratingsandtodriveourvehiclesfewer miles. To paraphrase Pogo: "I have met the. enemy, and it is my car."

The Scientists' Wake Up Call

The scientists say that we should no w be extremely worried about global warming (also commonly referred to as the greenhouse effect or climate change). They have long known that human activities are increasing the atmospheric concentrations of certain gases, most notably carbon dioxide but also methane, nitrous oxide, and certain man-made gases that trap heat that the earth would otherwise radiate to space. For example, average carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere have increased from 280 parts per million in the 1700s to 360 parts per million today. But, until recently, scientists were uncertain about whether this would cause global warming.

Scientists now express much greater confidence in their ability to link increased levels of greenhouse gases, rising temperatures, and environmental catastrophe. In January 1996, the United Nation's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, composed of 2,500 of the world's foremost climate experts, concluded that the "balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate." This sent shock waves around the world.

The U.N. scientists projected that, unless something is done to reduce future levels of greenhouse emissions, global temperatures could grow by 2 to 6 degrees Fahrenheit over the next century , a rate of increase never before seen on earth. The frightening consequences could include sea level rises up to 4 feet, severe flooding, exploding rates of tropical diseases such as malaria and dengue fever, much greater weather variability, huge changes in agricultural production, and species extinction.

The bottom line is that we are undertaking a massive real-time experiment with the earth's atmosphere. Of course, the consequences of global warming may be better or worse than scientists project. But by the time we know with certainty, it will likely be far too late to do anything about it. The combination of potential catastrophe and scientific uncertainty makes global warming a particularly difficult issue for a world and a nation that typically act on environmental problems only when they are readily apparent.

The International Community Responds

The world community responded to the scientists' call to action at the historic U.N. meeting on global warming in Kyoto, Japan in December, 1997 . For the first time, industrialized countries agreed to legally binding greenhouse gas emission targets. The industrialized countries committed to reduce aggregate greenhouse emissions by an average of 5% below 1990 levels by the 2008-2012 period, and the U.S. agreed to a 7% reduction. This may not sound like much, but it represents a 30% reduction from projected U.S. emission levels based on continued economic growth.

Nevertheless, the Kyoto agreement must be viewed as a very modest beginning to combat global warming. The treaty agreed to by President Clinton and other world leaders must still be ratified by individual countries. The U.S. political debate over global warming will be highly contentious because every citizen and business in the country will likely be affected in some way. The Republican congressional leadership and most large corporations have already strongly opposed the Kyoto treaty, despite a recent Harris poll finding that 74% of the American public supports it.

Even more important, the Kyoto treaty establishes only moderate pollution limits and only for the industrialized countries. This is entirely appropriate since these nations currently emit the majority of greenhouse emissions and many times more on a per capita basis than the developing countries. Ultimately, we will need much greater reductions from the industrialized world, as well as commitments from the developing countries to restrain their pollution growth. For example, scientists project that we would need to instantaneously reduce carbon emissions by 50-70% if we wanted to stabilize atmospheric carbon levels at today's levels, and even larger emission reductions if we assume some future growth in the developing world. A comprehensive global warming agreement including both the industrialized and developing countries will surely take many years to negotiate.

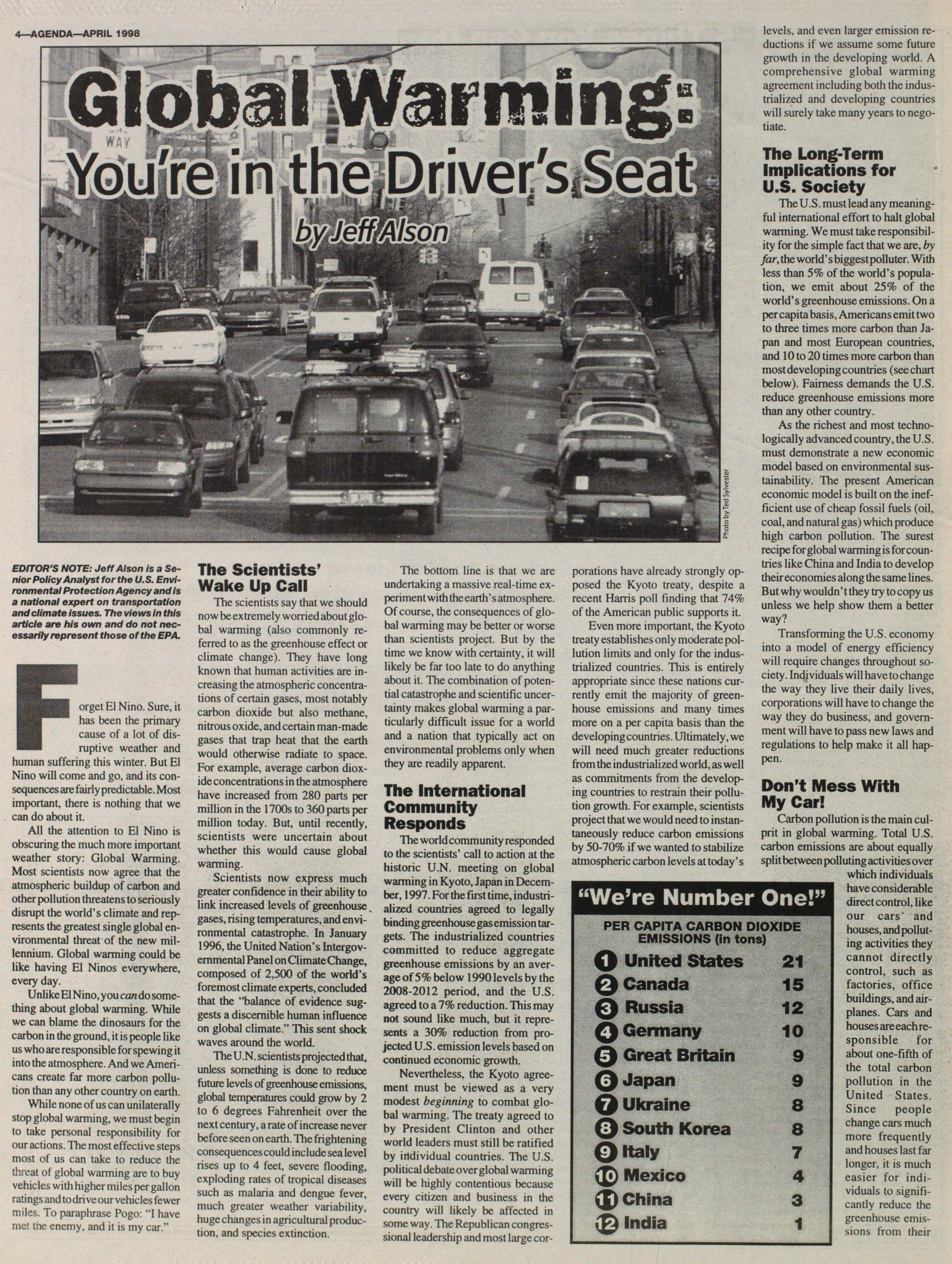

The Long-Term Implications for U.S. Society The U.S. must lead any meaningful international effort to halt global warming. We must take responsibility for the simple fact that we are, by far, the world's biggest polluter. With less than 5% of the world's population, we emit about 25% of the world's greenhouse emissions. On a per capita basis, Americans emit two to three times more carbon than Japan and most European countries, and 10 to 20 times more carbon than most developing countries (see chart below). Fairness demands the U.S. reduce greenhouse emissions more than any other country.

As the richest and most technologically advanced country, the U.S. must demonstrate a new economic model based on environmental sustainability. The present American economic model is built on the inefficient use of cheap fossil fuels (oil, coal, and natural gas) which produce high carbon pollution. The surest recipe for global warming is for countries like China and India to develop their economies along the same lines. But why wouldn't they try to copy us unless we help show them a better way?

Transforming the U.S. economy into a model of energy efficiency will require changes throughout society . Individuals will have to change the way they live their daily lives, corporations will have to change the way they do business, and government will have to pass new laws and regulations to help make it all happen.

PER CAPITA CARBON DIOXIDE EMISSIONS (in tons)

1. United States 21

2. Canada 15

3. Russia 12

4. Germany 10

5. Great Britain 9

6. Japan 9

7. Ukraine 8

8. South Korea 8

9. Italy 7

10. Mexico 4

11. China 3

12. India 1

Don't Mess With My Car!

Carbon pollution is the main culprit in global warming. Total U.S. carbon emissions are about equally split between polluting activities over which individuals have considerable direct control, like our cars' and houses, and polluting activities they cannot directly control, such as factories, office buildings, and airplanes. Cars and houses are each responsible for about one-fifth of the total carbon pollution in the United States. Since people change cars much more frequently and houses last far longer, it is much easier for individuals to significantly reduce the greenhouse emissions from their cars than from their houses.

You may not be surprised to know that cars are not just cars anymore! Twenty years ago, everybody drove cars except for people who needed a pickup truck or full-size van to haul cargo. Today, conventional cars represent only one-half of all new vehicle sales in the U.S. People buy and drive pickup trucks, minivans, and large sport utility vehicles to do the same things as cars: to commute, to go to the store, to take the kids to school. Conventional cars now represent less than half of the U.S. vehicle sales for "car companies" such as Ford and Chrysler. In this article, "car" will be used to represent any type of personal vehicle.

Cars are big carbon polluters in the U.S. for two simple reasons. One, Americans love to drive big and fast vehicles that travel fewer miles per gallon (mpg) than vehicles any where else in the world. Two, we have become dependent on lifestyles in which we drive our vehicles more miles per year than drivers any where else in the world.

The main reason we drive low mpg cars so many miles is the very low price of gasoline. The simple facts are that Americans currently pay less for gasoline, adjusted for inflation, than at any time in our country's history, and gasoline is cheaper here than in any other industrialized country. Think about it, gasoline costs a little over $1 a gallon, while milk and soft drinks cost $2-3 per gallon, orange juice costs $4-5 a gallon, and other liquid. Consumer products such as anti-freeze, dish soap, and mouthwash cost as much as $10 per gallon. Because of much higher gasoline taxes to discourage excess consumption, people in Japan and Europe pay $3-5 per gallon for gasoline.

It is one of the great American paradoxes that we love to complain about the price of gasoline. Many people seem to gauge the health of the national economy on whether gasoline price is up or down, any proposal to raise the gasoline tax a nickel a gallon causes political uproar, and friends boast that they drive across town to save a few cents per gallon. My all-time favorite was waking up one morning to National Public Radio and hearing "You would have to drive to Georgia to get the lowest gasoline price in the U.S."! You can bet that NPR would never waste time reporting where milk or bread was cheapest. (Do they actually think that someone in Chicago is going to drive to Georgia so they can save a dollar at the pump?)

Of course, in terms of our personal budgets and collective standard of living, low gasoline prices are wonderful. Who doesn't enjoy seeing the price of gasoline, or anything else for that matter, drop?

But while cheap gasoline is good for our pocketbooks, it is also taking us on a ride toward global warming. There is very little economic motivation to care about how much gasoline we use. If gasoline were more expensive, more people would buy fuel efficient cars and we would have lower carbon pollution. If gasoline were more expensive, more people would live closer to work and we would have lower carbon pollution.

Very few people think about mpg when they purchase a new vehicle. Most people are willing to spend money on power, size, utility, and luxury, but are not willing to pay for higher mpg. Surveys by the car companies show that it is the 20th most important attribute, next to "quality of the air conditioning system!" Car companies can only sell what people will buy, and so they are building more huge, low-mpg sport utility vehicles and fewer small, high-mpg cars. Over the last 10 years, the average horsepower level for new vehicles has increased by almost 50% and average weight has increased by nearly 15%. Accordingly, average mpg has declined slightly.

We constantly find way s to drive our gas guzzling vehicles more miles. Total U.S. miles traveled exploded since the end of World War II, doubling from 1950 to 1970, and again from 1970 to 1990. And why not , the gasoline cost of travel for the average car owner is now about 5 cents per mile. Adjusted for inflation, this is one-half of what American drivers paid in 1970 before that decade' soil price shocks and only one-third of the peak gasoline cost per mile in 1980-81.

At a nickel per mile, the gasoline cost of travel is so small as to be irrelevant unless you are low income or drive very high annual mileage. When was the last time you cancelled a trip because you could not afford the cost of the gasoline to get there? A European official put it another way in a recent speech, "America is the only country in the world where people drive to a health club in order to ride an exercise bicycle!"

Buying gas guzzlers and driving them long distances are leading us toward global warming. What do we do? One strategy would be for government to take the lead. In fact, sooner or later government will have to be part of a broad societal solution, because there are just too many people and corporations that won't change their behavior until bribed or forced to do so.

There are many government policies that could slow the vehicle contribution to global warming: higher gasoline taxes, increased corporate average fuel economy standards for the car companies, more funding for breakthrough automotive and renewable fuels technologies, and more comprehensive transit systems, to name just a few. Providing consumers with a major federal income-tax credit for the purchase of extremely high mpg vehicles was one idea I proposed to White House policy makers last fall. Recently, President Clinton proposed to Congress that such a tax break be offered beginning in 2000. Ideally, government at all levels would send complementary signals to manufacturers and consumers alike promoting lower gasoline consumption and carbon pollution.

Unfortunately, all of the government policies that could make a real difference are politically controversial for one reason or another: they cost money, they require government mandates on the private sector, or, as in the case of higher gasoline taxes, they are very unpopular with voters. There is simply no way that government is going to "mess with peoples' cars" unless and until there is much greater public concern about global warming. So, if government isn't going to try to reduce the car' s contribution to global warming anytime soon, what can be done on an individual level?

Your Choices Matter

If you are concerned about the threat of global warming and want to do your part to maintain a healthy environment for your children and grandchildren, there are things that you can do now that don't require the government to get its act together first. The easiest actions relate to your car and how you use it.

One option is to get rid of your car. This is somewhat more realistic in Ann Arbor than in most places, with its compact and lively downtown, excellent transit system, access to Amtrak, network of bike paths, and proximity to the resources and events at the University of Michigan. If you are single, go to school or work downtown, and have a simple lifestyle, it may be possible to go without a car.

But is dumping your car realistic if you have a family and are already feeling strapped for time trying to juggle the demands of jobs, schools, day care, shopping, and family outings? For better or worse, the American lifestyle is built around the unprecedented mobility of the car and the automotive genie is not likely to go back into the bottle anytime soon. It is crazy to expect more than a tiny minority of Americans to completely give up their personal vehicles.

No, cars are important to us and to our lifestyles. But by making smart decisions and choices, you can retain the mobility you need while reducing your car's contribution to global warming.

The two most important choices that you can make are the mpg of your vehicle and how many miles you drive your vehicle. There are other actions that you can take to minimize your car's carbon emissions, and which also protect your investment in your car: regular tune-ups, inflating your tires properly, and minimizing idling, high speeds, and "jack rabbit" stops and starts. But the most important factors, by far, are your vehicle 's mpg and how many miles you drive.

How can you tell how much carbon dioxide pollution your vehicles are throwing into the atmosphere? Pretty easily, as it turns out. You can approximate the total carbon dioxide emissions per year from your family vehicles with the following simple equation:

Total Miles Driven Per Year [divided by] Average MPG [divided by] 100 [equals] Total Carbon Dioxide Emissions in Tons

How can you tell if you emit more or less pollution than other families? A "typical" family with two adults would, on average, drive about 25,000 miles per year and their vehicles would average about 18 mpg. Plugging these numbers into the above equation shows that this typical family's vehicles emit about 14 tons of carbon dioxide each year. If you are in a family with two adults and your vehicles emit more than 14 tons per year, then your vehicles emit more carbon dioxide than those of most other families. If your family vehicles emit less than 14 tons per year, then your family emits less carbon dioxide pollution than average.

Your family can emit much more or much less than this average, of course. If your family drives a total of 45,000 miles per year with a large car and a sport utility vehicle that each averages only 15 mpg, your annual vehicle carbon dioxide emissions are 30 tons. On the other hand, if your family drives only 15,000 miles per year with two small cars that average 30 mpg, your family 's vehicles only emit 5 tons. The vehicles in the first family are responsible for 6 times more carbon dioxide that the vehicles in the second family!

The above equation can also help you understand the carbon dioxide consequences of specific decisions. Let's say you are in the market for a new vehicle. You have decided on a particular car model, but you have a decisión to make. You can buy the "base" version with a smaller engine and manual transmission that gets about 25 mpg, or you can pay extra for the "performance" version with a larger engine and automatic transmission that gets about 20 mpg. Now, 5 mpg may not sound like a lot, but if you drive 14,000 miles per year, the 20 mpg vehicle will emit about 1.5 tons more carbon dioxide than the 25 mpg vehicle each and every year. If you own the vehicle for ten years, that is a difference of 15 tons!

More remarkably, if you drive a large sport utility vehicle that only gets 12 mpg, you will emit 7 tons of carbon dioxide more per year, or 70 tons more over a 10-year period, than a neighbor who drives a 30 mpg car!

Or, let's say you are deciding to buy or rent one of two houses. One house is 5 miles from your job and the other is 1 5 miles from your job. If you move into the second house, you will drive 20 miles extra each day , or about 5,000 additional miles a year, and if you drive an 1 8 mpg vehicle you will emit almost 3 tons more carbon dioxide each year.

In a more extreme example, if you commute 25 miles each way over a 20-year period, you would emit 100 more tons of carbon dioxide than a work colleague who commutes only 5 miles!

I am not suggesting that, if you purchase a large sport utility vehicle or commute a long distance, you don't care about the environment in general or global warming in particular. The decisions about what type of vehicle to buy or where to live are complex and involve many important factors unrelated to the environment. But you should recognize that you do have choices, and that your decisions have environmental consequences.

The next time you buy a vehicle, try to buy one that has the highest mpg possible for the utility that you really need (many people spend thousands of dollars to get 4-wheel drive or towing capability that they rarely use). The next time you move to a different residence, try to li ve as close to your job as possible. These are the most important actions you can take to reduce the threat of global warming. They really do matter. ■

Cars are important to us and to our lifestyles ... and by making smart decisions and choices, you can retain the mobility you need while reducing your car's contribution to global warming.

5 Things You Can Do

(to be a Greener Driver)

1. Buy a Vehicle with Higher MPG.

2. Drive Fewer Miles.

3. Perform Regular Maintenance on Your Vehicle.

4. Drive Smart: Minimize Idling, Speeding, Fast Starts & Stops.

5. Vote Green: Support Green Governmental Policies.