Ceiling Projectors Made By Ann Arbor Firm Allow Bed-Ridden Patients To Read Books

Ceiling Projectors Made By Ann Arbor Firm Allow Bed-Ridden Patients To Read Books

By Alice Ziegler

Probably the most helpless feeling in the world is to be flat on your back, unable to move or do anything for yourself day after day but stare at the ceiling.

But thanks to an ingenious ceiling projector made in Ann Arbor and available to bed-bound patients of the county through the Ann Arbor Public Library, even the most helpless patient can find entertainment in staring at the ceiling.

There is no case on record of a patient who cannot operate a ceiling projector—even if he can only move a hand, a toe or his head.

Harold Schumann, a 23-year-old polio patient at the Ann Arbor Convalescent Home, for example, can only move his head from left to right—but he can read any of a variety of books by moving his head to the right and pressing a button with his cheek.

Another patient, Doris Shine at Beyer Memorial Hospital in Ypsilanti, is flat on her back with a fractured hip and broken right wrist suffered in an automobile accident. She uses her left hand to operate the buttons.

Schumann, stricken with polio in August, 1952, when he was a bricklayer's apprentice near Lansing, has been at the local convalescent home since last September.

He spends 17 of every 24 hours under a portable respirator and is unable to move arms and legs. While it would be impossible for him to sit up or hold a book, he can read a whole book, unassisted, after the projector is set up and the control button placed near his cheek.

A projector designed to throw the image on the ceiling instead of the wall is threaded with a book reel—that is a book, pictured page by page on narrow film similar to movie film. The control button, on a panel about one by five inches in size, is placed in position and the patient can read a page, and then advance the film to the next page by merely pressing the button.

In Harold Schumann’s case, his brother has built the buttons up higher so they are easier to operate with his cheek.

Miss Shine, a stenographer at the Parts and Equipment Manufacturing Division of Ford Motor Co., in Ypsilanti, uses the control panel as it is—operating the three buttons—starting button, advance button and reverse button—with her left hand.

While she will be "helpless” for a shorter time than Schumann, the hours still are long and tedious and she, too, is an enthusiastic user of projected books.

The projector is the invention of Eugene B. Power, president of University Microfilms, Inc., a firm devoted to publishing and copying books on film.

The idea first came to him when he was flat in bed with a fractured pelvis, suffered in a horseback riding accident. However, he didn’t carry it out until World War II, after he had seen many veterans lying helpless and wishing for something to do.

The ordinary projector would not operate properly when tipped up to cast the image on the ceiling, and it was necessary to design a special projector with a mirror to throw the image up-

A successful model was built. Soon more were under production and some books were copied on film. The first models were distributed to veterans hospitals.

By 1947, hospitals began to empty and many veterans were in civilian life. The demand had slacked off, and Power and his associates turned to the problem of adapting them to civilian life.

The need was there, as it is today. Power estimates there are as many as 50,000 potential users in the United States, but someone has to buy the projectors, distribute and service them and find those needing them.

Projected Books, Inc., is a nonprofit corporation, manufacturing projectors and books on film and selling them at cost. At cost, however, a projector and sufficient number of books on film posts about $300.

In 1947, the Ann Arbor Lions Club took over the job of not only raising money to provide some community projectors but also of servicing and distributing them to patients. The Ann Arbor Public Library agreed to house and handle them as an added service.

The library now has eight projectors, furnished by Lions and other community organizations.

The example of the Ann Arbor Lions Club has since been followed by about 600 other clubs across the country. Many libraries have added projected books to their services and some hospitals, such as University Hospital, have their own projectors and book-of-film libraries.

While more than $750,000 worth of projectors have been sold across the country, including a few in Europe, the project sponsors believe many more patients could find satisfaction and relaxation in them if they were available and prospective users knew about them.

More than 800 titles have been filmed, of which the local library has 113 adult titles and 28 juvenile titles. Most of the books are of the lighter variety preferred by patients.

They cover a wide range of interests—novels, detective stories, sports, biography, travel and adventure, science, tall tales, religion and textbooks to help student patients keep up with their studies.

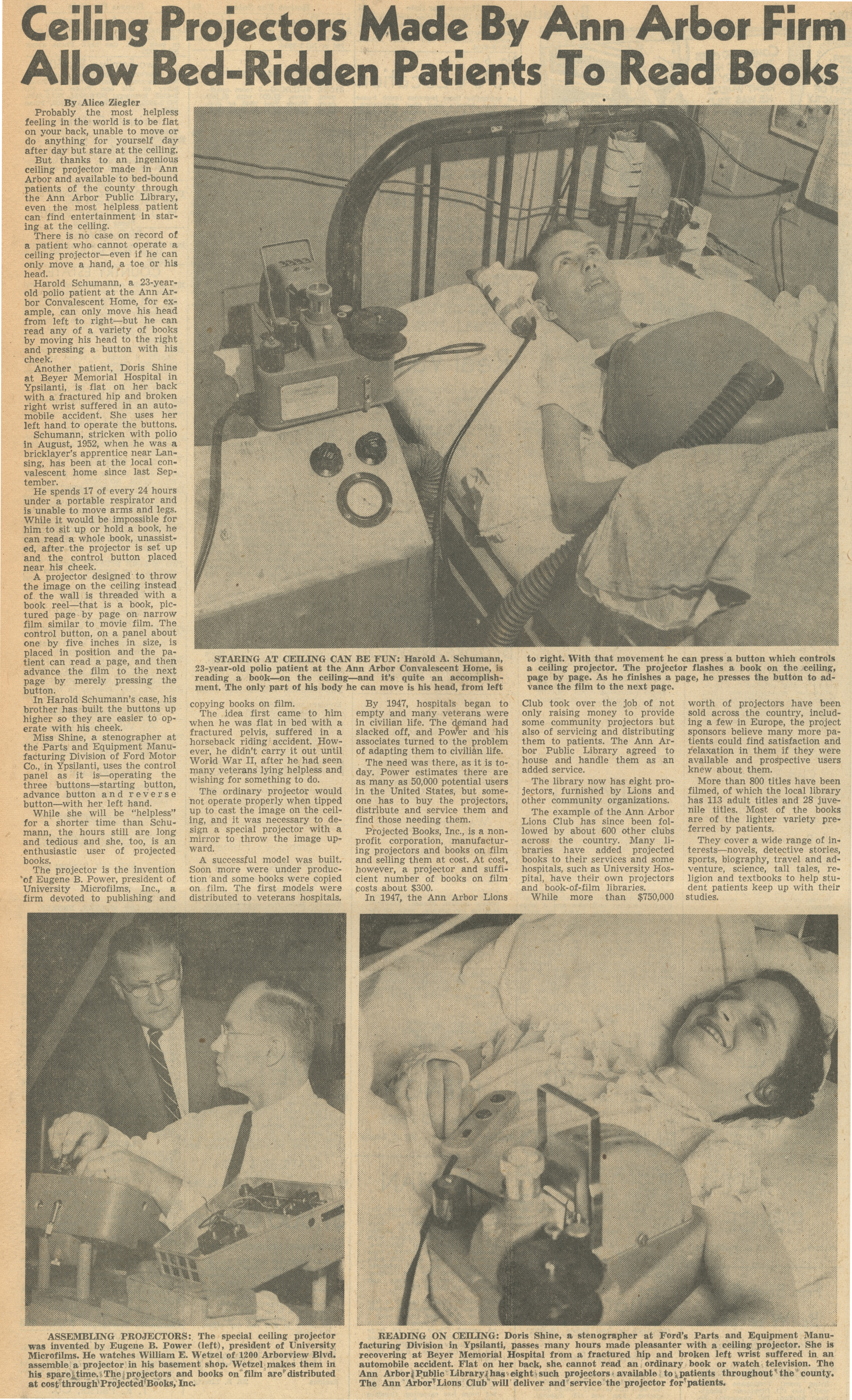

STARING AT CEILING CAN BE FUN: Harold A. Schumann, 23-year-old polio patient at the Ann Arbor Convalescent Home, is reading a book – on the ceiling – and it’s quite an accomplishment. The only part of his body he can move is his head, from left to right. With that movement, he can press a button which controls a ceiling projector. The projector flashes a book on the ceiling, page by page. As he finishes a page, he presses the button to advance the film to the next page.

ASSEMBLING PROJECTORS: The special ceiling projector was invented by Eugene B. Power (left), president of University Microfilms. He watches William E. Wetzel of 1200 Arborview Blvd. assemble a projector in his basement shop. Wetzel makes them in his spare time. The projectors and books on film are distributed at cost through Projected Books, Inc.

READING ON CEILING: Doris Shine, a stenographer at Ford's Parts and Equipment Manufacturing Division in Ypsilanti, passes many hours made pleasanter with a ceiling projector. She is recovering at Beyer Memorial Hospital from a fractured hip and broken left wrist suffered in an automobile accident. Flat on her back, she cannot read an ordinary book or watch television. The Ann Arbor Public Library has eight such projectors available to patients throughout the county. The Ann Arbor Lions Club will deliver and service the projector for patients.

Article

Subjects

Alice Ziegler

World War II

Veterans

University Microfilms

Projected Books Inc.

Polio

Inventions & Product Development

Ford Motor Company

Books & Reading

Beyer Memorial Hospital

Ann Arbor Public Library

Ann Arbor Convalescent Home

Accidents - Automobile

Ann Arbor Lions Club

Has Photo

Old News

Ann Arbor News

William E. Wetzel

Harold A. Schumann

Eugene B. Power

Doris Shine