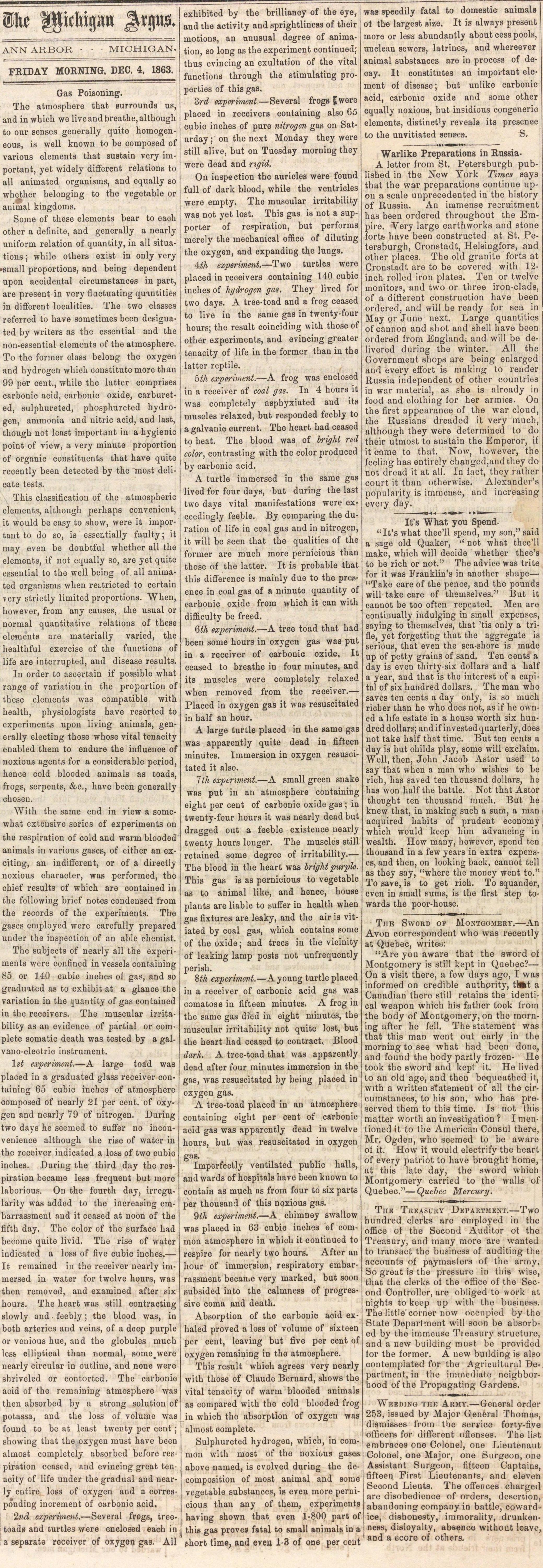

Gas Poisoning

The atmosphere that gurrounds us, and in which weliveandbreathe,although to our senses generally quite homogeneous, is well known to be composed of various elementa that sustain very important, yet widely different relations to all aniniated organisms, and equally so whether belonging to the vegetable or animal kingdoms. Some of these elements bear to each other a definite, and generally a nearly uniform relation of quantity, in all situations ; while others exist in only very small proportions, and being dependent upon accidental circumstances in part, are present in very fluctuating quantities in different localities. The two classes referred to have sometimes been designated by writers as the essential and the non-essential elements of the atmosphere. To the former class belong the oxygen and hydrogen which constitute more than 99 per cent., while the latter comprises carbonic acid, carbonic oxide, carbureted, sulphureted, phosphureted hydrogen, ammonia and nitric acid, and last, though not least important in a hygienic point of view, a very minute proportiou of organic constituents that have quite recently been detected by the most delicate tests. This classification of the atmospheric elements, although perhaps convenieut, it would be easy to show, were it important to do so, is essectially faulty ; it inay even be doubtful whether all the elements, if not equally so, are yet quite essential to the well being of all auimated organisms when res-tricted to certain verv strictly limitcd proportions. When, however, from any causes, the usual or normal quantitative relations of these eletnënts are materially varied, the healthful exercise of the functions of life are interrupted, and disease results. In order to ascertain if possible what range of variation in the proportion of these elements was compatible with health, physiologists have resorted to experimenta upon living animáis, generally electing those whose vital tenacity enabled them to endure the influence of noxious agents for a considerable period, henee cold blooded animáis as toads, frogs, serpents, &c, have been generally chosen. With the same end in view a somewhat extensive series of experimenta on tha respiration of cold and warm blooded animáis in various gases, of cither an exciting, an indifferent, or of a directly noxioua character, was performed, the chief results of which are contained in the following brief notes condensed from the records of the experiments. The gases employed were carefully prepared under the inspection of an able chemist. The subjects of nearly all the experiments were confined in vessels containing 85 or 140 cubic inches oí gas. and so graduated as to exhibit at a glanee the variation in the rjuantity of gas contained in the receivers. The muscular irritability as an evidence of partial or complete somatic death was tested by a galvano-electric instrument. lst experiment. - A large toad was placed in a graduated glass receiver containing 65 cubic inches of atmosphere oomposed of nearly 21 per cent. of oxygen and nearly 79 of nitrogen. During two days he seemed to suffer no inconvenience although the rise of water in the receiver indicated a loss of two cubic inches. During the third day the rospiration became less frequent but more laborious. On the fourth day, irregularity was added to the increasing embarrassmenl and it ceased at noon of the fifth day. The color of the surface had become quite livid. The rise of water indicated a loss of five cubic inches. - It remained in the receiver nearly immersed in water for twelve hours, was then removed, and examined after six hours. The heart was still oontracting slowly and ■ feebly ; the blood was, in both arteries and veins, of a deep purple or venious hue, and the globules mueh less elliptioal than normal, somewere nearly circular in outline, and none were shriveled or contorted. The carbonic acid of the remaining atmosphere was then absorbed by a strong solution of potassa, and the loss of volume was fouud to be at least twenty per cent ; showing that the oxygen must have been almost completely absorbed before respiration ceased, and evineing great tenacity of life under the gradual and nearly entire loss of oxygen and a corresponding increment of oarbonic acid. 'ind experiment. - Several frogs, treetoads and turtles were enclosed each in a separate receiver of oxygen gas. All exhibited by the brillianoy of the eye, and the activity and sprightliness of their motious, an unusual degree of animation, so long as the experiment continued; thus evincing an exultation of the vital functions through tho stimulating properties of this gas. Srd experiment. - Several frogs f were placed in reoeivers containing also 65 cubic inches of pure nitrogen gas on Saturday ;' on the next Monday they were still alive, but on Tuesday morning they were dead and ngid. On inspection the auricles were found full of dark blood, while the ventricles ■were empty. Tho muscular irritability was not yet lost. This gas is not a supporter of respiration, but performs merely the mechanïcal office of diluting the oxygeü, and expanding the lungs. 4tt experiment. - Two turtles were placed in receivers containing 140 cubic inches of hydrogen gas. They lived for two days. A tree-toad and a frog ceased to live in the same gas in twenty-four hours; the result coinciding with those of other experimenta, and evincing greater tenacity of life in the former than in the latter reptile. hth experiment. - A frog was enclosed in a receiver of coal gas. In 4 hours it was completely asphyxiated and lts muscles relaxed, but responded feebly to a galvanie current. The heart had ceased to beat. The blood was of bright red color, contrasting with the color produced by carbonic acid. A turtle immersed in the samo gas lived for four days, but during the last two days vital manifestations were exccedingly feeble. By comparing the duration of life in coal gas and in nitrogen, it will be seen that the qualities of the former are much more pernicious than those of the latter. It is probable that this difference is mainly due to the presence in coal gas of a minute quantity of carbonic oxide from whieh it can with difficulty be freed. Qth experiment. - A tree toad that had been some hours in oxygen gas was put in a receiver of carbonic oxide, It ceasod to breathe in four minutes, and its muscles were completely relaxed when removed from the receiver. - Placed in oxygen gas it was resuscitated in half an hour. A large turtle placed in the same gas was apparently quite dead in fifteen minutes. Immersion in oxygen resuscitated it also. Ith experiment. - A small green snake was put in an atmosphere containing eight per cent of carbonic oxide gas ; in twenty-four hours it was nearly dead but dragged out a feeble existence uearly twenty hours longer. The muscles still retained some degree of irritability. - The blood in the heart was Iright purple. This gas is as pernicious to vegetable as to animal like, and henee, house plants are liable to suffer in health when gas fixtures are leaky, and the air is vitiated by coal gas, which contains some of the oxide ; and trees in the vicinity of leaking lamp posts not unfrequently perish. 8th experiment. - A young turtle placed in a receiver of carbonic acid gas was comatosa in fifteen minutes. A frog in the same gas di'ed in eight minutos, the muscular irritability not quite lost, but the heart had ceased to contract. Blood dark. A tree-toad that was apparently dead after four minutes immersion in the gas, was resuscitated by being placed in oxygen gas. A tree-toad placed in an atmosphere containing oight per cent of carbonic acid gas was .apparently dead in twelve hours, but was resuscitated in oxygen gas. Imperfeetly ventilated public halls, and wards of hospitals have been known to contain as much ns from four to six parts per thousand of this noxious gas. 9th experiment. - A chimney swallow was placed in 63 cubio inches of common atmosphere in which it continued to respire for nearly two hours. After an hour of immersion, respiratory embarrassment became very marked, but soon subsided into the calmness of progressive coma and death. Absorption of the carbonic acid exhaled proved a loss of volume of sixteen per cent, leaving but five per cent of oxygen remaining in the atmosphere. This result which agrees very nearly with those of Claude Bernard, shows the vital tenacity of warm blooded animáis as compared with the cold blooded frog in which the absorption of oxygen was almost complete. Sulphureted hydrogen, which, in common with most of tho noxious gases above nanied, is evolved during the decomposition of most animal and some vegetable substances, is even more peruicious than any of them, experiments having shown tbat even 1-800 part of this gas proves fatal to small animáis in a ghort time, and even 1-3 of ono per ceut was speedily fatal to domestie anímala ot the largest size. It is always present more or lesa abundantly about cesa pools, unelean sewers, latrines, and whereever animal substances are in process of decay. It constitutes an important element oí disease; but unlike carbonic acid, carbonie oxide and some other equally noxious, but insidious congenerio elements, distinet'y revéala its presence to the unvitiated seoa-ea.

Article

Subjects

Old News

Michigan Argus