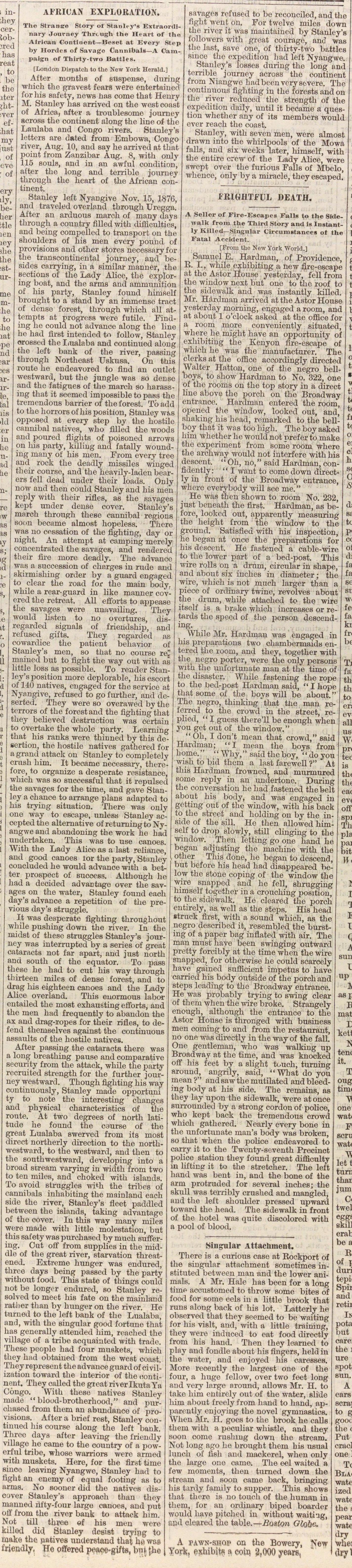

African Exploration

[London Disp&tcli to the New York Herald.] After montlis of Bttspense, during wJiich the gravest fears were entertained forhis safety, news lias come that Henry M. Stanley has arrived on the west ooast of África, after a troublesome journey across the continent along the line of the Laulaba and Congo rivers. Stanley's letters are dated from Embowa, Congo river, Aug. 10, and say he arrived at that point from Zanzíbar Aug. 8, with only 115 souls, and in an awXul condition, after the long and terrible journey through the lieart of the African continent. Stanley left Nyangive Nov. 15, 1876, and traveled overland througli Uregga. Aft-er an arduous march of many days tlirough a country filled with difficulties, and being compelled to transport on the shoulders of his men every pound of provisions and other stores necessary f or the transcontinental journey, and besides carrying, in a similar manner, the sections of the Lady Alice, the exploring boat, and the arms and ammunition of his party, Stanley found himself brought to a stand by an immense tract of dense forest, through which all attempts at progresa were futile. landing he could not advance along the line he had flrst intended to follow, Stanley oroesed the Iiualaba and continued along the left bank of the river, passing through Northeast Uskusa. On tuis route he endeavored to flnd an outlet westward, but the jungle was so dense and the fatigues of the march so harassing that it seemed impossible to pass the tremendous barrier of the forest. Tó add to the horrors of hia position, Stanley was opposed at every step by the hostile eannibal natives, who fllled the woods and poured flights of poisoned arrows on his party, killing and fatally wounding nmny of his men. From every tree and rock the deadly missiles wïnged their course, and the heavily-laden bearers feil dead under their loads. Only now and then could Stanley and his men reply with their rifles, as the savages kept under dense cover. Stanley's march through these eannibal regions soon became almost hopeless. There was no cessation of the fighting, day or night. An attempt at camping merely concentrated the savages, and rendered their fire more deadly. The advanco was a succession of charges in rude and skirmishing order by a guard engaged to clear the road for the main body. while a rear-guard in like marmer covered the retreat. All efforts to appease the savages were unavailing. They would listen to no overtures, disregarded signáis of friendship, and refused giits. They regarded as cowardice the patiënt of Stanley's men, so that no course re" mameu Dut to ngnt tne way out with as little loss as possible. To reader Stanley's position more deplorable, bis escort of 140 natives, cugaged for the service at Nyaagive, refused to go further, and deserted. ïhey were so overawed by the tenors of the forestand the fighting that they believed destruction was certaiu to overtake the whole party. Learning that bis ranks were thinned by this desertion, the hostilo natives gathered for a grand attack on Stanley to completely crush him. It became necessary, therefore, to organize a desperate resistance, which was so successful that it repulsed the savages for the time, and gave Stanley a chance to arrange plans adapted to his trying situation. There was only one way to escape, unlesa Stanley acceptedthe alternative ofreturningtoNyangwe and abandoning the work he had undertaken. This was to use canoes. With the Lady Alice as a last reliance, and good canoes tor the party, Stanley concluded he would advance with a better prospect of success. Although he had a decided advactage over the savages on the water, Stanley found each day's advance a repetition of the previous day's struggle. It was desperate fighting throughout wliile pushing down the river. In the midst of these struggles Stanley's journey was interrupted by a series of great cataracts not íar apart, and just north and south of tho equator. To pass these he had to cut his way through thirteen miles of dense forest, and to drag his eighteen canoes and the Lady Alice overland. This enormous labor entailed the most exhausting eflbrts, and the men had frequently to abandon the ax and drag-ropes for their rifles, to defend themselves against the continuous assaults of the hostile natives. After passing the cataracts there was a long breathing pause and comparative security froin the attack, while the party reoruited strength for the further journey westward. Though flghting his way oontinuously, Stanley made opportuni ty to note the interesting changes and physical characteristics of the route. At two degrees of north latitude he found the eaurse of the great Lualaba swerved f rom its most direct northerly direction to the northwestward, to the westward, and then to the southwestward, developing into a broad stream varying in width from two to ten miles, and choked with islands. To ayoid struggles with the tribes of cannibals inhabiting the mainland each side the river, Stanley's fleet paddled between the islands, taking advantage of the cover. In this way rnany miles were made with little molestation, but this saf ety was purchased by niuch suffering. Cut off from supplies in the middle of the great river, starvation threatened. Extreme hunger was endured, three days being passed by the party without food. This state of things could not be longer endured, so Stanley resolved to meet his fate on the mainland rather than by hunger on the river. He turned to the left bank of the Lualaba, and, with the singular good fortune that has generally attended him, reached the village of a tribe acquainted with trade. These people had four muskets, which they had obtained from the west coast. They represent the advance guard of ei vilization toward the interior of the oontinent. They called the great river Ikuta Ya Cóngo. With these natives Stanley made "blood-brotherliood," and purchased from them an abundance of provisions. After a brief rest, Stanley con;inued his course along the left bank. Three days after leaving the friendly village he carne to the country of a powerful tribe, whose warriors werc armed with muskets. Here, for the first time since leaving Nyangwe, Stanley had to ight an enemy of equal footing as to arms. No sooner lid the natives discover Stanley's approach than they manned öfty-four large canoes, and put off from the river bank to attack him. iot till thvee Of his men were killed did. Stanley desist trying to aake the uatives uuclerstand tha't was riendly, He pffered peaoe-gifts, bm ihr savages rcfused to be reconciled, and the fight went on. For twelve miles down the river it was maiutained by Stanley's followers with great courage, and was the last, save one, of thirty-two battles since the cxpedition had ïeft Nyangwe. Stanley's losses during the long and terrible journey across the continent from Niangwe had been vcrystvere. The eontinuons fighting in the forests and on the river reduced the strength of the expedition daily, until it became a question whether any of its members would ever reaeh the coast. Stanley, with seven men, were almost drawn into the whirlpools of the Mowa falls, and six weeks later, himself, with the entire crew of the Lady Alice, were swept over the fnrious Falls of Mbelo, whence, only by a miracle, they escaped.

Article

Subjects

Old News

Michigan Argus