Dr. Wessinger Still Going Strong At 87, After 40 Years As City Health Officer

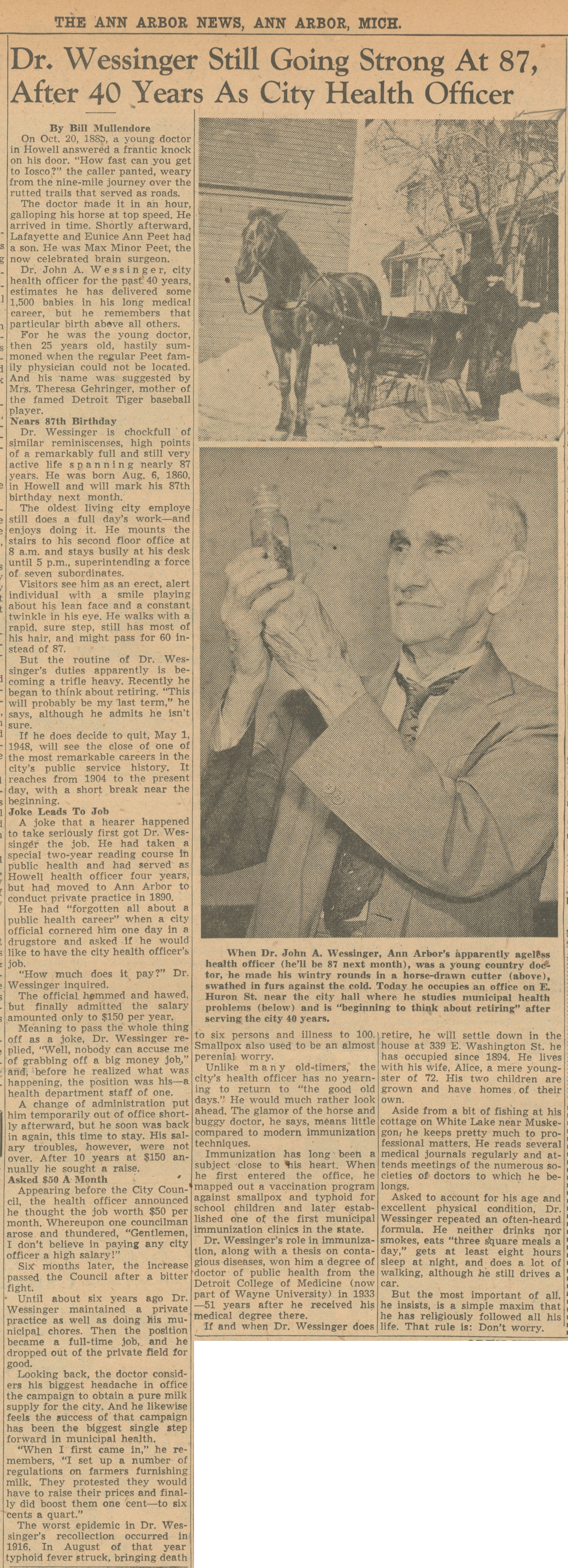

DR. WESSINGER STILL GOING STRONG AT 87, AFTER 40 YEARS AS CITY HEALTH OFFICER By Bill Mullendore On Oct. 20, 1885, a young doctor in Howell answered a frantic knock on his door. “How fast can you get to Iosco?” the caller panted, weary from the nine-mile journey over the rutted trails that served as roads. The doctor made it in an hour, galloping his horse at top speed. He arrived in time. Shortly afterward, Lafayette and Eunice Ann Peet had a son. He was Max Minor Peet, the now celebrated brain surgeon. Dr. John A. Wessinger, city health officer for the past 40 years, estimates he has delivered some 1,500 babies in his long medical career, but he remembers that particular birth above all others. For he was the young doctor, then 25 years old, hastily summoned when the regular Peet family physician could not be located. And his name was suggested by Mrs. Theresa Gehringer, mother of the famed Detroit Tiger baseball player. Nears 87th Birthday Dr. Wessinger is chockfull of similar reminiscenses, high points of a remarkably full and still very active life spanning nearly 87 years. He was born Aug. 6, 1860, in Howell and will mark his 87th birthday next month. The oldest living city employee still does a full day’s work—and enjoys doing it. He mounts the stairs to his second floor office at 8 a.m. and stays busily at his desk until 5 p.m., superintending a force of seven subordinates. Visitors see him as an erect, alert individual with a smile playing about his lean face and a constant twinkle in his eye. He walks with a rapid, sure step, still has most of his hair, and might pass for 60 instead of 87. But the routine of Dr. Wessinger’s duties apparently is becoming a trifle heavy. Recently he began to think about retiring. “This will probably be my last term,” he says, although he admits he isn’t sure. If he does decide to quit, May 1, 1948, will see the close of one of the most remarkable careers in the city’s public service histroy. It reaches from 1904 to the present day, with a short break near the beginning. Joke Leads To Job A joke that a hearer happened to take seriously first got Dr. Wessinger the job. He had taken a special two-year reading course in public health and had served as Howell health officer four years, but had moved to Ann Arbor to conduct private practice in 1890. He had “forgotten all about a public health career” when a city official cornered him one day in a drugstore and asked if he would like to have the city health officer’s job. “How much does it pay?” Dr. Wessinger inquired. The official hemmed and hawed, but finally admitted the salary amounted to only $150 per year. Meaning to pass the whole thing off as a joke, Dr. Wessinger replied, “Well, nobody can accuse me of grabbing off a big money job,” and, before he realized what was happening, the position was his̶a health department staff of one. A change of administration put him temporarily out of office shortly afterward, but soon he was back in again, this time to stay. His salary troubles, however, were not over. After 10 years at $150 annually he sought a raise. Asked $50 A Month Appearing before the City Council, the health officer announced he thought the job worth $50 per month. Whereupon one councilman arose and thundered, “Gentlemen, I don’t believe in paying any city officer a high salary!” Six months later, the increase passed the Council after a bitter fight. Until about six years ago Dr. Wessinger maintained a private practice as well as doing his municipal chores. Then the position became a full-time job, and he dropped out of the private field for good. Looking back, the doctor considered his biggest headache in office the campaign to obtain a pure milk supply for the city. And he likewise feels the success of that campaign has been the biggest single step forward in municipal health. “When I first came in,” he remembers, “I set up a number of regulations on farmers furnishing milk. They protested they would have to raise their prices and finally did boost them one cent—to six cents a quart.” The worst epidemic in Dr. Wessinger’s recollection occurred in 1916. In August of thatyear typhoid fever struck, bringing death to six persons and illness to 100. Smallpox also used to be an almost perennial worry. Unlike many old-timers, the city’s health officer has no yearning to return to “the good old days.” He would much rather look ahead. The glamor of the horse and buggy doctor, he says, means little compared to modern immunization techniques. Immunization has long been a subject close to his heart. When he first entered the office, he mapped out a vaccination program against smallpox and typhoid for schoolchildren and later established one of the first municipal immunization clinics in the state. Dr. Wessinger’s role in immunization, along with a thesis on contagious diseases, won him a degree of doctor of public health from the Detroit College of Medicine (nowpart of Wayne University) in 1933̶51 years after he received his medical degree there. If and when Dr. Wessinger does retire, he will settle down in the house at 339 E. Washington St. he has occupied since 1894. He lives with his wife, Alice, a mere youngster of 72. His two children are grown and have homes of their own. Aside from a bit of fishing at his cottage on White Lake near Muskegon, he keeps pretty much to professional matters. He reads several medical journals regularly and attends meetings of the numerous societies of doctors to which he belongs. Asked to account for his age and excellent physical condition, Dr. Wessinger repeated an often-heard formula. He neither drinks nor smokes, eats “three square meals a day,” gets at least eight hours of sleep at night, and does a lot of walking, although he still drives a car. But the most important of all, he insists, is a simple maxim that he has religiously followed all his life. That rule is: Don’t worry. PHOTO CAPTION: When Dr. John A. Wessinger, Ann Arbor’s apparently ageless health officer (he’ll be 87 next month), was a young country doctor, he made his wintry rounds in a horse-drawn cutter (above), swathed in furs against the cold. Today he occupies an office on E. Huron St. near the city hall where he studies municipal health problems (below) and is “beginning to think about retiring” after serving the city 40 years.