A Nightmare Comes to Life

A NIGHTMARE COMES TO LIFE

By CHRISTOPER POTTER

NEWS FILM WRITER

Suppose you'd been living in the same house in the same neighborhood for years, even decades.

Suppose you were suddenly ordered to vacate your house for the sole reason that somebody else wanted to buy it, irrespective of your own wishes.

Suppose you resisted, and subsequently found yourself bodily evicted by the authorities, who then leveled not only your home, but the entire neighborhood as well.

Sound like a script for some far-away totalitarian nightmare? Guess again.

It happened in Detroit three years ago, when 3,500 city residents were forcibly turned out of their homes in order to make way for a still-unfinished General Motors Cadillac plant.

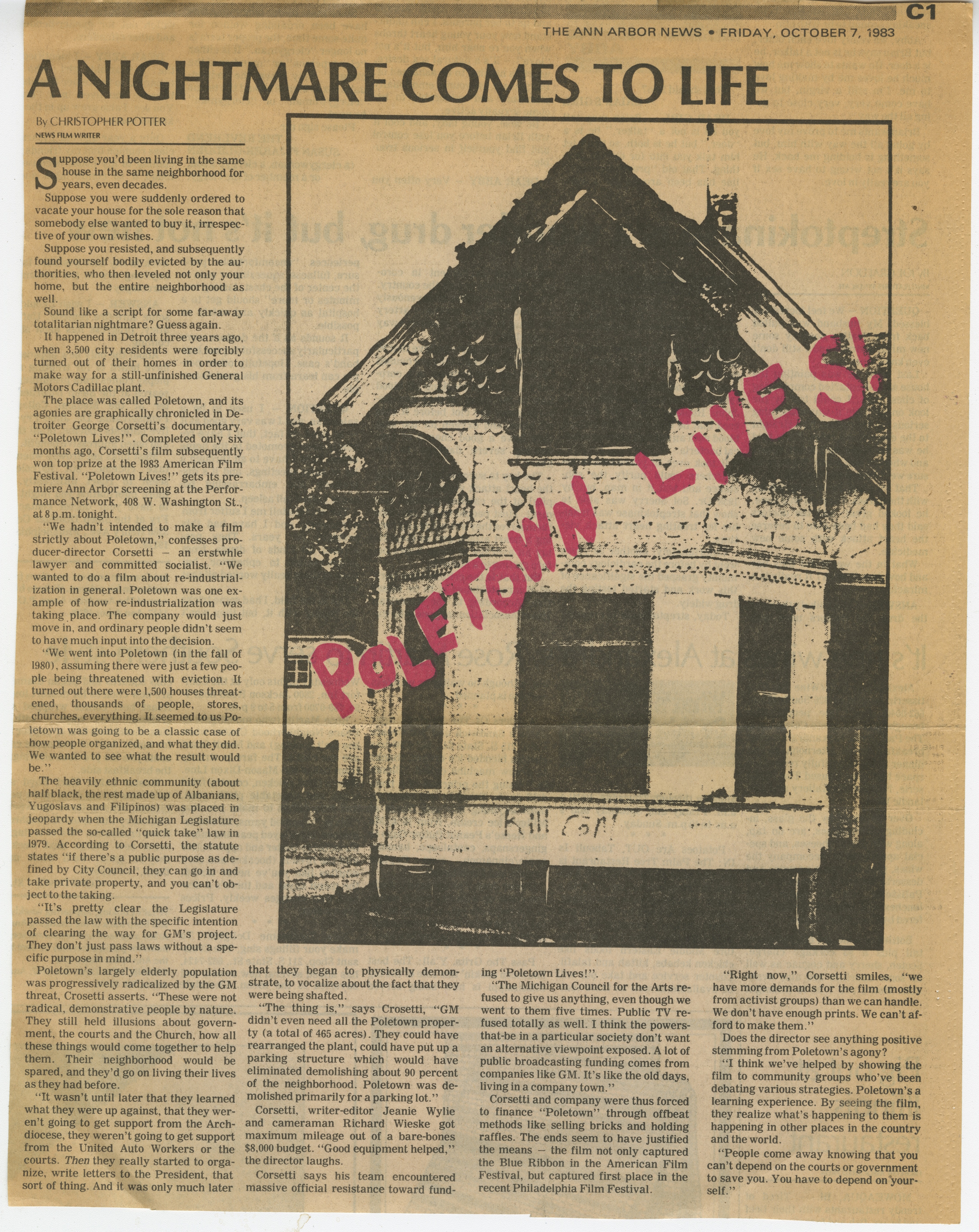

The place was called Poletown, and its agonies are graphically chronicled In Detroiter George Corsetti’s documentary, "Poletown Lives!". Completed only six months ago, Corsetti's film subsequently won top prize at the 1983 American Film Festival. "Poletown Lives!” gets its premiere Ann Arbpr screening at the Performance Network, 408 W. Washington St., at 8p.m. tonight.

"We hadn’t intended to make a film strictly about Poletown,” confesses producer-director Corsetti - an erstwhile lawyer and committed socialist. "We wanted to do a film about re-industrialization in general. Poletown was one example of how re-industrialization was taking place. The company would just move in, and ordinary people didn't seem to have much input into the decision.

"We went into Poletown (in the fall of 1980). assuming there were just a few people being threatened with eviction. It turned out there were 1,500 houses threatened, thousands of people, stores, churches, everything. It seemed to us Poletown was going to be a classic case of how people organized, and what they did. We wanted to see what the result would be."

The heavily ethnic community (about half black, the rest made up of Albanians, Yugoslavs and Filipinos) was placed in jeopardy when the Michigan Legislature passed the so-called "quick take" law in 1979. According to Corsetti, the statute states "if there’s a public purpose as defined by City Council, they can go in and take private property, and you can’t object to the taking.

"It’s pretty clear the Legislature passed the law with the specific intention of clearing the way for GM’s project. They don’t just pass laws without a specific purpose in mind.”

Poletown’s largely elderly population was progressively radicalized by the GM threat. Crosetti asserts. “These were not radical, demonstrative people by nature. They still held illusions about government, the courts and the Church, how all se things would come together to help them. Their neighborhood would be spared, and they’d go on living their lives as they had before.

"It wasn't until later that they learned what they were up against, that they weren't going to get support from the Archdiocese, they we from the United Auto Workers or the courts. Then they really started to organize, write letters to the President, that sort of thing. And it was only much later that they began to physically demonstrate, to vocalize about the fact that they were being shafted.

"The thing is," says Crosetti, “GM didn’t even need all the Poletown property (a total of 465 acres). They could have rearranged the plant, could have put up a parking structure which would have eliminated demolishing about 90 percent of the neighborhood. Poletown was demolished primarily for a parking lot.”

Corsetti, writer-editor Jeanie Wylie and cameraman Richard Wieske got maximum mileage out of a bare-bones $8,000 budget. "Good equipment helped,” the director laughs.

Corsetti says his team encountered massive official resistance toward funding "Poletown Lives!".

The Michigan Council for the Arts refused to give us anything, even though we went to them five times. Public TV refused totally as well. I think the powers-that-be in a particular society don't want an alternative viewpoint exposed. A lot of public broadcasting funding comes from companies like GM. It's like the old days, living in a company town."

Corsetti and company were thus forced to finance "Poletown" through offbeat methods like selling bricks and holding raffles. The ends seem to have justified the means - the film not only captured the Blue Ribbon in the American Film Festival, but captured first place in the recent Philadelphia Film Festival.

"Right now," Corsetti smiles, "we have more demands for the film (mostly from activist groups) than we can handle. We don't have enough prints. We can't afford to make them."

Does the director see anything positive stemming from Poletown's agony?

"I think we've helped by showing the film to community groups who've been debating various strategies. Poletown's a learning experience. By seeing the film, they realize what's happening to them is happening in other places in the country and around the world.

"People come away knowing that you can't depend on the courts or government to save you. You have to depend on yourself."