Ann Arbor Yesterdays ~ From Bakery Boy To Famous Sculptor

From Bakery Boy To Famous Sculptor

Ann Arbor Yesterdays

By Lela Duff

During the first few years after the arrival of Allen and Rumsey on this primeval bit of Washtenaw soil, the Rogers family came from York State with their eight children. The youngest of these was Randolph, a little boy whose first memories, he said later, were of Ann Arbor. With the Allen children and other, pioneer youngsters, Randolph no doubt waded or fished in Allen's Creek, hunted or picked wild flowers in Eber White’s or Hiscock’s woods, was not unfamiliar with Indians and the cry of wolves, and received his only formal education in the little brick building which by then had been erected on the far corner of Jail Square. He was afterwards remembered as having been full of fun, and especially gifted as a mimic.

We do not know how early it was noticed that he could draw; but it was in his early teens, as an apprentice in the bakery of Calvin and D. W. Bliss, that he began fashioning three-dimensional figures out of dough, or even, when his employers were not present, out of butter.

Having no urge to become a baker and being equally restive in his brother’s mill in Jackson, young Randolph settled for a few years for a job as clerk in a Main St. drygoods store owned by Gen. J. D. Hill. In his off time he practiced many skills: drawing, whittling, molding, portrait painting, and copper engraving. His woodcuts found a ready market with the Michigan Argus, since in those days they were the chief way of illustrating newspapers. He received ten dollars from an Ann Arbor paper for the wood engraving of a log cabin and flags which became the emblem of William Henry Harrison in the presidential campaign of 1840.

In 1848 he went to New York in hope of finding an apprenticeship to an engraver, but failing that, took a clerk's position again in the “Silk House” of Edgerton and Stuart.

So far as I can find out, up to his arrival in New York he had never even seen a statue except no doubt the cemetery variety. Eager to develop his innate ability, he got hold of a block or marble and some tools and set about chiseling a bust of Byron with 'only a small picture as model. The result was so successful that it drew the attention of his employer, John Stuart, jr., who immediately offered to loan him the money to go to Florence, Italy, to study under the famous sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini.

There his development was so rapid and his works were so much in demand that on his return to America six years later he had $6,000 left after paying back his benefactor.

At this time he must have come to visit his relatives in Ann Arbor, and it may have been then and here that he made the acquaintance of Prof. Henry S. Frieze, the young Latin teacher and musician who came to the U-M faculty that very year. At any rate, two years later Frieze visited the studio Rogers had set up in Rome in the meantime and was much impressed. He brought back photographs of Rogers’ work for the University. By 1859 we find Rogers writing a warm and friendly letter to Prof. Frieze discussing the terms under which his statue “Nydia” could be bought.

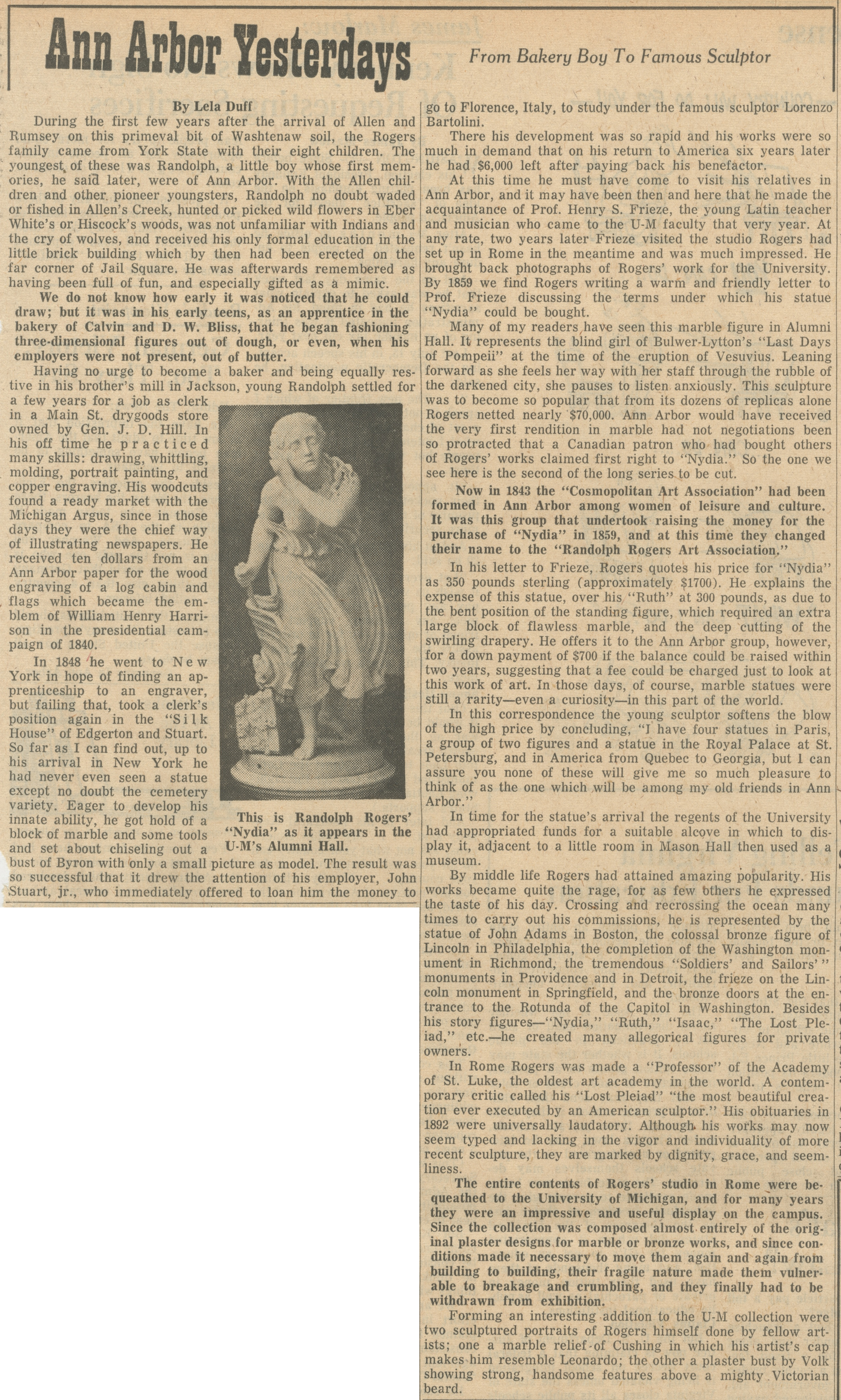

Many of my readers have seen this marble figure in Alumni Hall. It represents the blind girl of Bulwer-Lytton’s “Last Days of Pompeii” at the time of the eruption of Vesuvius. Leaning forward as she feels her way with her staff through the rubble of the darkened city, she pauses to listen anxiously. This sculpture was to become so popular that from its dozens of replicas alone Rogers netted nearly $70,000. Ann Arbor would have received the very first rendition in marble had not negotiations been so protracted that a Canadian patron who had bought others of Rogers’ works claimed first right to “Nydia.” So the one we see here is the second of the long series to be cut.

Now in 1843 the “Cosmopolitan Art Association” had been formed in Ann Arbor among women of leisure and culture.

It was this group that undertook raising the money for the purchase of “Nydia” in 1859, and at this time they changed i their name to the “Randolph Rogers Art Association.”

In his letter to Frieze, Rogers quotes his price for “Nydia" as 350 pounds sterling (approximately $1700). He explains the expense of this statue, over his “Ruth” at 300 pounds, as due to the bent position of the standing figure, which required an extra large block of flawless marble, and the deep cutting of the swirling drapery. He offers it to the Ann Arbor group, however, for a down payment of $700 if the balance could be raised within two years, suggesting that a fee could be charged just to look at this work of art. In those days, of course, marble statues were still a rarity—even a curiosity—in this part of the world.

In this correspondence the young sculptor softens the blow of the high price by concluding, "I have four statues in Paris, a group of two figures and a statue in the Royal Palace at St. Petersburg, and in America from Quebec to Georgia, but I can assure you none of these will give me so much pleasure to think of as the one which will be among my old friends in Ann Arbor."

In time for the statue’s arrival the regents of the University had appropriated funds for a suitable alcove in which to display it, adjacent to a little room in Mason Hall then used as a . museum.

By middle life Rogers had attained amazing popularity. His works became quite the rage, for as few others he expressed the taste of his day. Crossing and recrossing the ocean many times to carry out his commissions, he is represented by the statue of John Adams in Boston, the colossal bronze figure of Lincoln in Philadelphia, the completion of the Washington monument in Richmond, the tremendous “Soldiers’ and Sailors’ ” monuments in Providence and in Detroit, the frieze on the Lincoln monument in Springfield, and the bronze doors at the entrance to the Rotunda of the Capitol in Washington. Besides his story figures—"Nydia,” “Ruth,” “Isaac,” "The Lost Pleiad,” etc.—he created many allegorical figures for private owners.

In Rome Rogers was made a “Professor” of the Academy of St. Luke, the oldest art academy in the world. A contemporary critic called his “Lost Pleiad” “the most beautiful creation ever executed by an American sculptor.” His obituaries in 1892 were universally laudatory. Although, his works may now seem typed and lacking in the vigor and individuality of more recent sculpture, they are marked by dignity, grace, and seemliness.

The entire contents of Rogers’ studio in Rome were bequeathed to the University of Michigan, and for many years they were an impressive and useful display on the campus. Since the collection was composed almost entirely of the original plaster designs for marble or bronze works, and since conditions made it necessary to move them again and again from building to building, their fragile nature made them vulnerable to breakage and crumbling, and they finally had to be withdrawn from exhibition.

Forming an interesting addition to the U-M collection were two sculptured portraits of Rogers himself done by fellow artists; one a marble relief of Cushing in which his artist's cap makes him resemble Leonardo; the other a plaster bust by Volk showing strong, handsome features above a mighty Victorian beard.

This is Randolph Rogers’ block of marble and some tools “Nydia” as it appears in the U-M's Alumni Hall.

Article

Subjects

Lela Duff

Local History

Ann Arbor Yesterdays

Sculpture

Bakeries & Confectioners

Michigan Argus

Artists

University of Michigan - Faculty & Staff

Alumni Hall

Cosmopolitan Art Association

Randolph Rogers Art Association

University of Michigan - Board of Regents

Mason Hall

Has Photo

Old News

Ann Arbor News

Randolph Rogers

Calvin Bliss

D. W. Bliss

J. D. Hill

John Stuart Jr.

Lorenzo Bartolini

Henry S. Frieze