Of News writer and his popular column

THE ANN ARBOR NEWS

A•10

Christman brings self into scene

In today's chapter of Ann Arbor Diary, Professor Christman reluctantly brings himself into the picture as the inventor of the carbon monoxide test which, with some modifications because of modern equipment, has been used for decades. He mentions his work in that field to introduce R. Ray Baker, a former Ann Arbor News editor and science writer who wrote a popular column called "Bobby and the Old Professor."

By Adam Christman

In August 1978 Mrs. Mary Crit-chell, then on the Teaching and Learning Communities staff, asked if I would contribute an ar-ticle on rose culture for the Neigh-bors Page of The Ann Arbor News.

Since I was reluctant to write on this subject, already belabored in many garden magazines, she sug-gested that some topic related to my research in biochemistry might be of interest.

Although hopefully none of my research problems would qualify for the "Golden Fleece" award of Sen. Proxmire, only one might be of interest to the general public.

Carbon monoxide poisoning was more of a problem 50 years ago than at present. Nevertheless, there are more deaths at the present time in which carbon monoxide is a contributing factor than is generally recognized.

THE MAIN purpose of this se-ries of articles has been to recall interesting and important people who were active in Ann Arbor in the first half of the present century.

A brief discussion of my involvement in the studies on carbon monoxide poisoning will serve this purpose since it will introduce several people I met because of my work in this field. One of these people was R. Ray Baker, an Ann Arbor News reporter-editor who wrote a popular science column.

The exhaust gases of modern motor cars, compared to those of 50 years ago, contain minimal concentrations of carbon monoxide.

In the 1920s, traffic policemen working during the rush hours at the busy intersections of the nar-row downtown streets of Philadel-phia would often collapse. This in-dicated that the motor vehicles of that time were indeed contami-nating the air with a lethal gas.

Analysis of the blood of the traf-fic policeman showed a high con-tent of carbon monoxide. This resulted in an inadequate supply of oxygen to the brain (anoxia) and dizziness.

RALPH NADER was not with us in the 1920s, but his predeces-sors soon raised the question as to whether some highway accidents written off as "driving while in-toxicated" might be due to the ac-cumulation of carbon monoxide in closed cars.

If the driver insisted he had not been drinking but before the acci-dent had developed an intense throbbing headache, a diagnosis of carbon monoxide poisoning was probably correct. Convenient methods for a quick on-the-spot analysis of alcohol or carbon monoxide levels in expired air or blood were not available in the 1920s or 1930s.

Before 1922, when a separate Department of Physiological Chemistry was established in the University of Michigan Medical School, Dr. Herbert Emerson of the Department of Bacteriology, Physiological Chemistry and Hy-giene (chairman - Dr. Novy) was assigned the task of checking blood suspected of containing car-bon monoxide.

HE WAS well aware that the spectroscopic method he used was inadequate unless a high lev-el of carbon monoxide hemoglo-bin was present. Moreover if there had been a delay of several hours before a blood sample was taken and if the subject during this period had breathed pure air, the carbon monoxide hemoglobin would have decreased below the level detectable by the spectroscopic method.

Since the Writer had on several occasions served as a consultant to Dr. Emerson, and the old, di-rect vision spectroscope had now become part Of the equipment of the new department, the unhappy task of checking blood samples for carbon Monoxide was as-signed to the writer.

Since I had a negative attitude concerning the spectroscopic examination, a quantitative gasometric method was adopted as a standard procedure. Although this method would accurately measure all levels of carbon monoxide it was time con-suming and in the hands of a la-bratory technician might yield positive results in the absence of carbon monoxide.

Moreover all tie steps in this procedure had to be completed before it could be established that carbon monoxide was absent. What was needed was a fool-proof, relatively vapid, qualitative test to determine whether the use of a longer quantitative method was justified.

In 1932 at the meeting of the American Society of Biological Chemists held at Philadelphia, I was able to report such a method. Although the details of the method would be of little interest to the average reader, the key reaction involves a change tf, palladium chloride in solution t . readily ob-servable particles of metallic palladium.

THIS REACTION is similar to the process used 40 years later in the catalytic converters of motor vehicles by which carbon monox-ide of exhaust gases i4 converted to carbon dioxide.

Although my preliminary report did not produce headlines in the New York Times of the Wall Street Journal, the quantitative procedure developed during the next year was accepted in medical-legal circles as proof that carbon monoxide was or was not involved in deaths which were under court investigation.

During the years 1932-1936 several graduate students in biochemistry served as assistants. One of these men, Walter P. Block, now professor of nutrition in the School of Public Health and an associate professor of biological chemistry, reminded me recently that his stipend for the school year for 10 to 15 hours of work per week was $400.

DURING the winter of 1932-33 the writer visited several of the larger commercial garages in Ann Arbor to inquire if the mechanics had noted any ill effects after working eight hours in an at-mosphere obviously loaded with the exhaust gases of motors.

The garages were closed during the extreme cold weather, and cars were being towed in to be thawed and started. At this early date, exhaust fans in the garages were not required by law. All the workers reported that they suf-fered from severe headaches before the end of the work day. The headaches were gone after a few hours in fresh air.

Permission was obtained to take samples of blood from some of the workers near the end of the work period. The results showed a dangerous level of carbon monox-ide in all of the samples.

The level of total hemoglobin in the blood of the garage workers was also about 10-15 percent higher than average for men. This gave the workers a small safety factor if part of their hemoglobin was tied up with carbon monoxide and was thus unable to deliver ade-quate amounts of oxygen to the brain and other tissues.

AT THE SPRING meeting of the Michigan Academy of the Sci-ences, Arts and Letters held on the campus of the University of Michigan in March 1933, the writ-er presented a paper dealing with the new method of carbon monoxide. Undoubtedly, to make it more interesting to the diverse group of scientists in the audience, some of the practical aspects of carbon monoxide poisoning were discussed.

The Ann Arbor News reporter R. Ray Baker was in the audi-ence, and his report in the March 17, 1933, edition of The News was picked up by news media all over the country.

Although Baker was the associate editor of The News his chief interest was science news. He was in effect the Larry Bush and Max Gates of the 1930s,and 1940s.

Perhaps because of my affiliation with the Medical School, I received letters, long distance telephone calls and even tele-grams from people who thought a treatment was available for vic-tims of carbon monoxide who had suffered irreverable brain dam-age due to long exposure to high levels of carbon monoxide.

I HAVE NEVER understood how Baker's simple report brought this response. Although I was married for several months, the contact made with the ener-getic, resourceful Ray Baker made it worthwhile. During the next 15 years he often appeared at my office, sometimes requesting information on some subject but more often seeking the names of University staff members who might be consulted.

Ray Baker had a wide range of interests. One of his articles pub-lished in the Booth Newspapers in the mid 1930s was later published in the book "Before Man in Michi-gan." The c000peration of profes-sor Russell C. Hussey of the University of Michigan Geology Department for help with this book is acknowledged.

Baker also wrote about the ear-ly Indian tribes of Michigan. For this subject he had excellent authorities for consultation, namely Emerson Greenman, professor of archeology at the U-M, named custodian of Michigan archeology after he was named dean emeri-tus of the School of Homeopathic Medicine.

A point of local interest was a report in The Ann Arbor News of April 5, 1939, of the finding of an ancient Indian arrow in Burns Park by Virgil Fairbanks, son of the famous sculptor Avard Fairbanks.

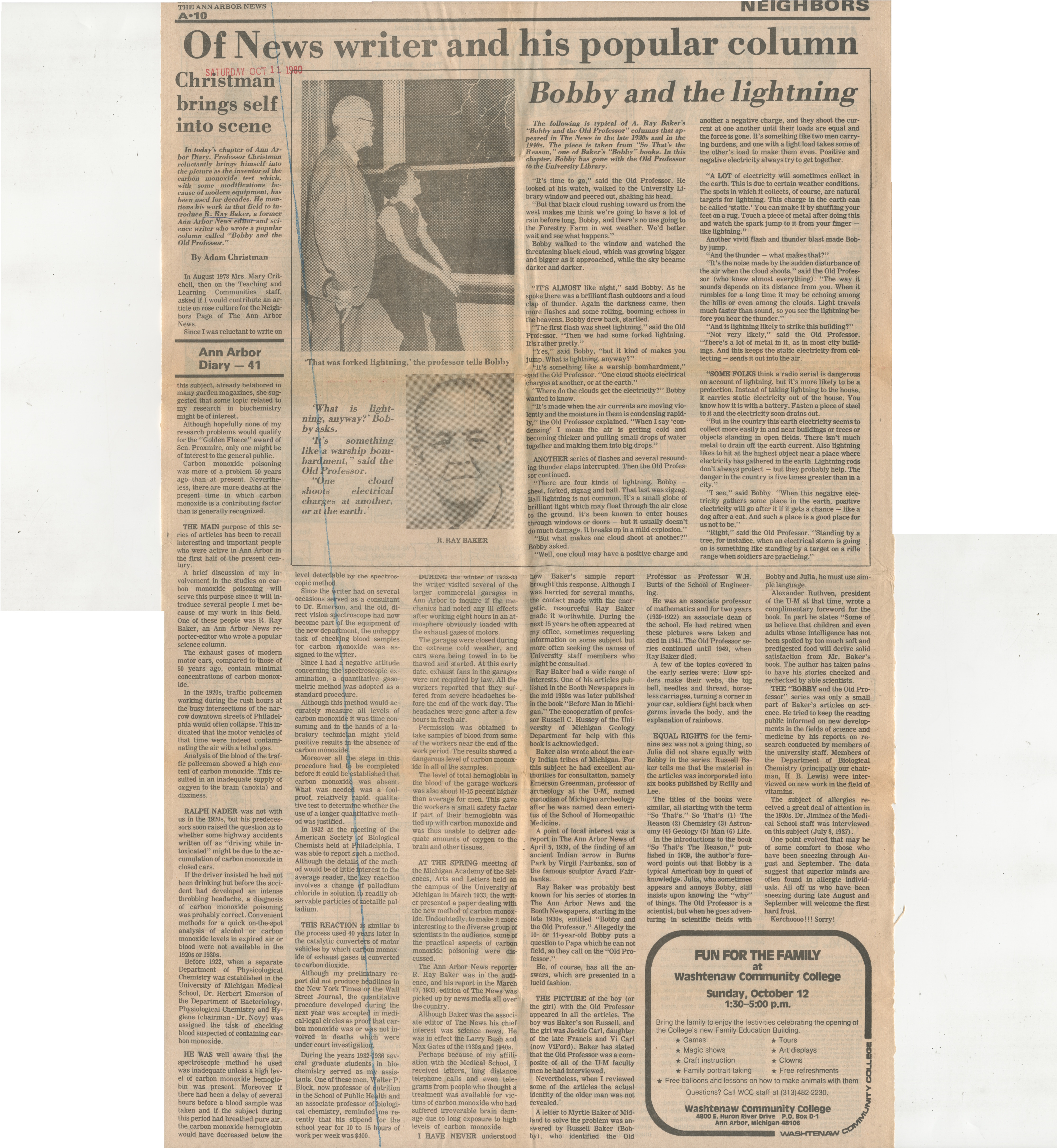

Ray Baker was probably best known for his series of stories in The Ann Arbor News and the Booth Newspapers, starting in the late 1930s, entitled "Bobby and the Old Professor." Allegedly the 10- or 11-year-old Bobby puts a question to Papa which he can not field, so they call on the "Old Professor."

He, of course, has all the an-swers, which are presented in a lucid fashion.

THE PICTURE of the boy (or the girl) with the Old Professor appeared in all the articles. The boy was Baker's son Russell, and the girl was Jackie Carl, daughter of the late Francis and Vi Carl (now ViFord) . Baker has stated that the Old Professor was a com-posite of all of the U-M faculty men he had interviewed.

Nevertheless, when I reviewed some of the articles the actual identity of the older man was not revealed.

A letter to Myrtle Baker of Mid-land to solve the problem was an-swered by Russell Baker (Bob-by) , who identified the Old Professor as Professor W.H. Butts of the School of Engineering.

He was an associate professor of mathematics and for two years (1920-1922) an associate dean of the school. He had retired when these pictures were taken and died in 1941. The Old Professor series continued until 1949, when Ray Baker died.

A few of the topics covered in the early series were: How spi-ders make their webs, the big bell, needles and thread, horseless carriages, turning a corner in your car, soldiers fight back when germs invade the body, and the explanation of rainbows.

EQUAL RIGHTS for the feminine sex was not a going thing, so Julia did not share equally with Bobby in the series. Russell Ba-ker tells me that the material in the articles was incorporated into six books published by Reilly and Lee.

The titles of the books were similar, all starting with the term "So That's." So That's (1) The Reason (2) Chemistry (3) Astron-omy (4) Geology (5) Man (6) Life.

In the introductions to the book "So That's The Reason," pub-lished in 1939, the author's fore-word points out that Bobby is a typical American boy in quest of knowledge. Julia, who sometimes appears and annoys Bobby, still insists upon knowing the "why" of things. The Old Professor is a scientist, but when he goes adven-turing in scientific fields with Bobby and Julia, he must use simple language.

Alexander Ruthven, president of the U-M at that time, wrote a complimentary foreword for the book. In part he states "Some of us believe that children and even adults whose intelligence has not been spoiled by too much soft and predigested food will derive solid satisfaction from Mr. Baker's book. The author has taken pains to have his stories checked and rechecked by able scientists.

THE "BOBBY and the Old Professor" series was only a small part of Baker's articles on sci-ence. He tried to keep the reading public informed on new develop-ments in the fields of science and medicine by his reports on research conducted by members of the university staff. Members of the Department of Biological Chemistry (principally our chair-man, H. B. Lewis) were interviewed on new work in the field of vitamins.

The subject of allergies received a great deal of attention in the 1930s. Dr. Jiminez of the Medi-cal School staff was interviewed on this subject (July 8, 1937).

One point evolved that may be of some comfort to those who have been sneezing through Au-gust and September. The data suggest that superior minds are often found in allergic individ-uals. All off us who have been sneezing during late August and September will welcome the first hard frost. Kerchoooo! ! ! Sorry!

_____________________________

FUN FOR THE FAMILY at Washtenaw Community College Sunday, October 12 1:30-5:00 p.m.

Bring the family to enjoy the festivities celebrating the opening of the College's new Family Education Building. * Games * Tours * Magic shows * Art displays * Craft instruction * Clowns * Family portrait taking * Free refreshments * Free balloons and lessons on how to make animals with them Questions? Call WCC staff at (313)482-2230.

Washtenaw Community College 4800 E. Huron River Drive P.O. Box 0-1 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106

_______________________________

Bobby and the lightning

The following is typical of A. Ray Baker's "Bobby and the Old Professor" columns that ap-peared in The News in the late 1930s and in the 1940s. The piece is taken from "So That's the Reason," one of Baker's "Bobby" books. In this chapter, Bobby has gone with the Old Professor to the University Library.

"It's time to go," said the Old Professor. He looked at his watch, walked to the University Li-brary window and peered out, shaking his head. "But that black cloud rushing toward us from the west makes me think we're going to have a lot of rain before long, Bobby, and there's no use going to the Forestry Farm in wet weather. We'd better wait and see what happens." Bobby walked to the window and watched the threatening black cloud, which was growing bigger and bigger as it approached, while the sky became darker and darker.

"IT'S ALMOST like night," said Bobby. As he spoke there was a brilliant flash outdoors and a loud clap of thunder. Again the darkness came, then more flashes and some rolling, booming echoes in the heavens. Bobby drew back, startled. "The first flash was sheet lightning," said the Old Professor. "Then we had some forked lightning. It’s rather pretty." `Yes," said Bobby, "but it kind of makes you p. What is lightning, anyway?" 'Ws something like a warship bombardment," said the Old Professor. "One cloud shoots electrical charges at another, or at the earth." "Where do the clouds get the electricity?" Bobby wanted to know. "It's made when the air currents are moving vio-lently and the moisture in them is condensing rapid-ly," the Old Professor explained. "When I say 'condensing' I mean the air is getting cold and becoming thicker and pulling small drops of water together and making them into big drops." ANOTHER series of flashes and several resound-ing thunder claps interrupted. Then the Old Profes-sor continued. "There are four kinds of lightning, Bobby —sheet, forked, zigzag and ball. That last was zigzag. Ball lightning is not common. It's a small globe of brilliant light which may float through the air close to the ground. It's been known to enter houses through windows or doors — but it usually doesn't do much damage. It breaks up in a mild explosion." "But what makes one cloud shoot at another?" Bobby asked. "Well, one cloud may have a positive charge and another a negative charge, and they shoot the cur-rent at one another until their loads are equal and the force is gone. It's something like two men carry-ing burdens, and one with a light load takes some of the other's load to make them even. Positive and negative electricity always try to get together.

"A LOT of electricity will sometimes collect in the earth. This is due to certain weather conditions. The spots in which it collects, of course, are natural targets for lightning. This charge in the earth can be called 'static.' You can make it by shuffling your feet on a rug. Touch a piece of metal after doing this and watch the spark jump to it from your finger —like lightning." Another vivid flash and thunder blast made Bob-by jump. "And the thunder — what makes that?" "It's the noise made by the sudden disturbance of the air when the cloud shoots," said the Old Profes-sor (who knew almost everything) . "The way it sounds depends on its distance from you. When it rumbles for a long time it may be echoing among the hills or even among the clouds. Light travels much faster than sound, so you see the lightning before you hear the thunder." "And is lightning likely to strike this building?" "Not very likely," said the Old Professor. "There's a lot of metal in it, as in most city build-ings. And this keeps the static electricity from collecting — sends it out into the air.

"SOME FOLKS think a radio aerial is dangerous on account of lightning, but it's more likely to be a protection. Instead of taking lightning to the house, it carries static electricity out of the house. You know how it is with a battery. Fasten a piece of steel to it and the electricity soon drains out. "But in the country this earth electricity seems to collect more easily in and near buildings or trees or objects standing in open fields. There isn't much metal to drain off the earth current. Also lightning likes to hit at the highest object near a place where electricity has gathered in the earth. Lightning rods don't always protect — but they probably help. The danger in the country is five times greater than in a city." "I see," said Bobby. "When this negative elec-tricity gathers some place in the earth, positive electricity will go after it if it gets a chance — like a dog after a cat. And such a place is a good place for us not to be." "Right," said the Old Professor. "Standing by a tree, for instance, when an electrical storm is going on is something like standing by a target on a rifle range when soldiers are practicing."

Article

Subjects

Adam Christman

University of Michigan - School of Engineering

University of Michigan - Geology Department

Science Journalism

Reilly & Lee Co.

Literature

Children's Literature

Books & Authors

Bobby and the Old Professor

Ann Arbor News

Bobby and the Old Professor

Has Photo

Old News

Ann Arbor News

William Henry Butts

Russell Ray Baker

Russell C. Hussey

R. Ray Baker

Mary Critchell

Jackie Carl

H. B. Lewis

Alexander Grant Ruthven

Eck Stanger