A Career Jeopardized By Faith In An Incredible Tale

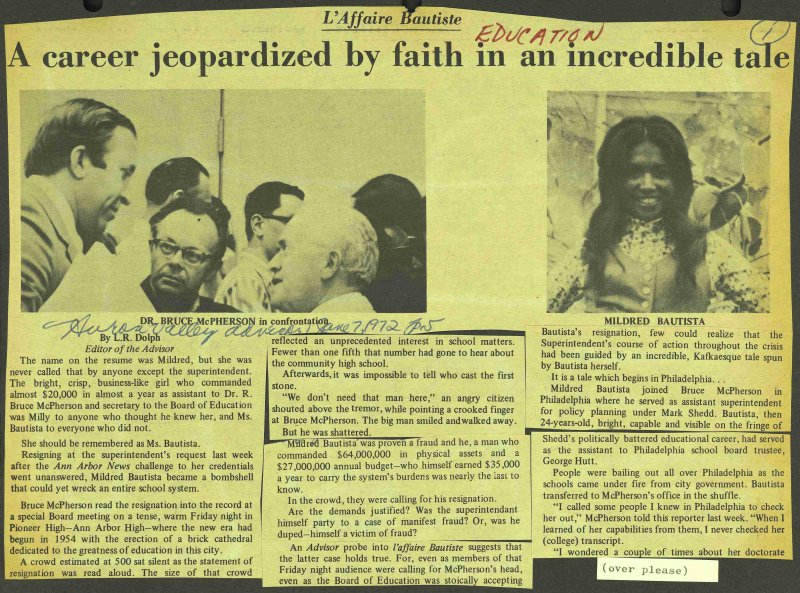

The name on the resume was Mildred, but she was never called that by anyone except the superintendent. The bright, crisp, business-like girl who commanded almost $20,000 in almost a year as assistant to Dr. R. Bruce McPherson and secretary to the Board of Education was Milly to anyone who thought he knew her, and Ms. Bautista to everyone who did not. She should be remembered as Ms. Bautista. Resigning at the superintendent's request last week after the Ann Arbor News challenge to her credentials went unanswered, Mildred Bautista became a bombshell that could yet wreek an entire school system. Bruce McPherson read the resignation into the record at a special Board meeting on a tense, warm Friday night in Pioneer High-Ann Arbor High- where the new era had begun in 1954 with the erection of a brick cathedral dedicated to the greatness of education in this city. A crowd estimated at 500 sat silent as the statement of resignation was read aloud. The size of that crowd reflected an unprecedented interest in school matters. Fewer than one fifth that number had gone to hear about the community high school. Afterwards, it was impossible to teil who cast the fust stone. "We don't need that man here," an angry citizen shouted above the tremor, while pointing a crooked finger at Bruce McPherson. The big man smiled andwalked away. But he was shattered. I "■""MMr&fl. Bautista was proven a traud and he, a man who commanded $64,000,000 in physical assets and a $27,000,000 annual budget-who himself earned $35,000 a year to carry the system's burdens was nearly the last to know. In the crowd, they were calling for his resignation. Are the demands justified? Was the superintendant himself party to a case of manifest fraud? Or, was he duped-himself a victim of fraud? An Advisor probe into l'affaire Bautiste suggests that the latter case holds true. For, even as members of that Friday night audience were calling for McPherson's head, even as the Board of Education_was_stoically accepting Bautista's resignation, few could realize that the Superintendent's course of action throughout the crisis had been guided by an incredible, Kafkaesque tale spun by Bautista herself. It is a tale which begins in Philadelphia. . . Mildred Bautista joined Bruce McPherson in Philadelphia where he served as assistant superintendent for policy planning under Mark Shedd. Bautista, then 24-years-old, bright, capable and visible on the fringe of Shedd's politically battered educational career, had served as the assistant to Philadelphia school board trustee, George Hutt. People were bailing out all over Philadelphia as the schools came under fire from city government. Bautista transferred to McPherson's office in the shuffle. "I called some people I knew in Philadelphia to check her out," McPherson told this reporter last week. "When I learned of her capabilities from them, I never checked her (college) transcript. "I wondered a couple of times about her doctórate program, because it seemed strangely arranged. But I never thought much more about it." In Philadelphia, Bautista proved reliable, quick-witted and a helpful aide to McPherson's style of policy making. She was careful with detail work: perfect to clean up the , debris left in the wake of the sweeping policy changes whicn McPherson would eventually be called upon to implement by the Ann Arbor Board of Education. It was in Philadelphia that McPherson first saw Bautista get sick. She would grow weak and be confined to bed for days. Her normally healthy glow would fade to an ashen gray. It frightened everyone who saw it and McPherson saw it many times. She said it was a rare blood disease. Otherwise, Bautista was lively, tireless and always confident: qualities that were de rigeur for a junior officer on an embattled frigate. The public schools everywhere had begun to clear their decks for war. - ■ . She met Philip Mcllnay in McPherson's PMadelphia office. Both had been married. Both were divorced. They feil in love. Everyone could see it. . But bitterness and distrust and the awful grind of divorce proceedings kept them from another marriage. Once in Ann Arbor, they decided to live together. Mcllnay himself was brilliant, cool, a man who always I did his homework. He was a complicated man too, and Bautista kept him going when his nüiilism overrode his life I force. In Ann Arbor, the Board of Education began to falll under the McNamara-like spell of Mcllnay' s mind. I Nervous, soft-spoken, given to private rages, Mcllnayl nevertheless always knew where the figures for thel multi-mülion dollar budget were and what they meant. The teachers knew about the cohabitation by the timej of last year's strike. The board knew about it. Every newsman in town knew. - But Someone was bound to bring it up. And Someone did. Baustista one day complained to this reporter that the board met in exécutive session-in the days when the press was not admitted-and ordered she and Mcllnay to get mar ried. Framed against this backdrop of potential "scandal," much of Ann Arbor was still talking about the "new" administration-ten months after assuming office. Then the Ann Arbor News broke the story about Bautista. The day it was published, McPherson and this reporter talked for an hour. It was the first time the Advisor heard the story by which McPherson was to guide his subsequent actions. The superintendent was furious. A suit for libel was very much on his mind. McPherson told the Advisor that he had been assured by Bautista that she could produce proof that the News story was factually in error. Worse, she said, the story was cruel and everyone would feel very bad once they were exposed to the "truth". But the public could never be told she said. She might die as a consequence. The story that had gripped the big man so powerfully, so long, was this: Mildred Bautista was the victim of a rare blood disease, something akin to leukemia, which she had contracted about age 19. She should have died, but she didn't. Instead, a doctor performed a miracle cure: It was innovative, creative and it worked, she saicUÍTCryriéeíse had died, but she lived and the doctors didn't know why But the cure was illegal, she said. Bautista and Mcllnay sat in her office with this reporter as they unfolded the story. All the blood in her body had been drained añT replaced. She had spentmonths in the hospital. She should 'still have been there, but she refused. She wanted to go to '' school, she said, and if the doctors wouldn't let her, she would quit and go home. Doctors, with a miracle on their hands, dreamed of the Nobel Prize, she said. So, she claimed they sent her to school under an assumed name. She got her diploma in two years and made Phi Beta Kappa. j She wrote poems and articles and the doctors sent them to be published. And the doctors returned xeroxed I tearsheets to her. She never checked the publications themselves, shel said. But Bautista said she had the records in her apartment. I m inere was me certiiied diploma that no one had seen, a I gold Phi Beta Kappa key and those tearsheets from I publications whose existence no one could find. And then they turned up "missing". I The Mcllnay-Bautista apartment was broken into and I their personal effects rifled. Mcllnay called board member-and Ann Arbor policeman-Robert Conn. The I color televisión had not been taken, nor had any money. His effects had been searched,but nothing was missing I I he said. Nothing except the Bautista diploma, the Phi Beta I Kappa key and the tearsheets. Mcllnay remembered some of the poems. He had seen them when they first met, he said. He remembered them I because he told her "thev weren't very good." But Conn told Advisor staffer, Larry Randa, that the I break -in appeared staged. The Advisor dispatched a reporter to the apartment I complex. He examined the electro-magnetic lock on the I front door of the complex. It had not been forced. Mcllnay claimed that the front door hadn't been shut, I however. He had experienced troubles with his automobile, he I said, and the door had been propped open by the doormat I while he had gone to the dealer to check it out. Bautista appeared shattered by the experience. The records were now missing on both ends of the wire. She went on with her story. Because the cure was illegal, and the doctors thought J they were about to be discovered, they would disavow all I knowledge of her. She would be sick with no cure I available. Anyone who pushed the matter would kill her. It stopped McPherson dead in his tracks. Those around him who were privy to the story believed it after she told ' Bautista said she suspected that the doctors had faked everything to encourage her recovery. She said they had apparently built a make-believe universe for her to perpetúate this miracle cure they had performed. And to perpetúate their dreams of the Nobel Prize. McPherson was gullible. Others around him were too It was Cecü Warner. president of the Board ot Education, who directed Bruce McPherson to ily across the country to establish the truth. The superintendent drew the $3,000 remaining in his travel fund. Bautista and Mcllnay went with him. The Board, angry that they left, refused to cover their expenses. McPherson had spent half an hour in the Advisor office I telling us what he thought he could find in Caüfornia. He I went searching for some statement from the doctors I whom Bautista claimed were treating her. He wás convinced in the face of almost universal I skepticism that someone was out to "get her". Mildred Bautista took Bruce McPherson to California, I and looked squarely into the dead-end that met them I everywhere. Then a fact emerged almost joyfully. She had been valedictorian of her high school class. But nothing else. At home now, McPherson does not know what to I believe. Mildred Bautista had sat with his kids often. She I had been like family. Mrs. McPherson talked fondly of I her, worried about the dark light cast on her, and then in I the final analysis, worried more about her husband. Bautista herself had ridden it through all the way to the I end. When she resigned, the board had no legal basis on I which to demand it. She had been hired at the superintendent's request and I the board's pleasure. The job, paying $20,000 annuallyj was created by that nine-man body. There were nol professional requirements attached to the position. Other than the normal expectations that the person I filling the position not be a fraud, of course. So, she has resigned. In her wake she has left her boss's I career jeopardized. Has she harmed her own future? No one is talking. At 25, with a brilliant record in Philadelphia and high I efficiency ratings in Ann Arbor, she can probably look I forward to her next high paying job. Only McPherson ever called her Mildred. We called her Milly.

Article

Subjects

Ann Arbor News

Old News

Mildred Bautista