Yesterday

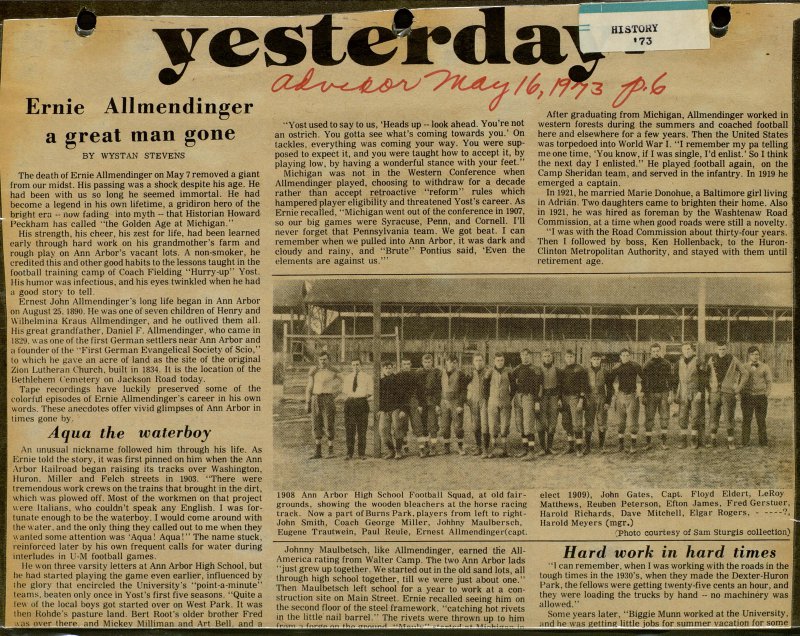

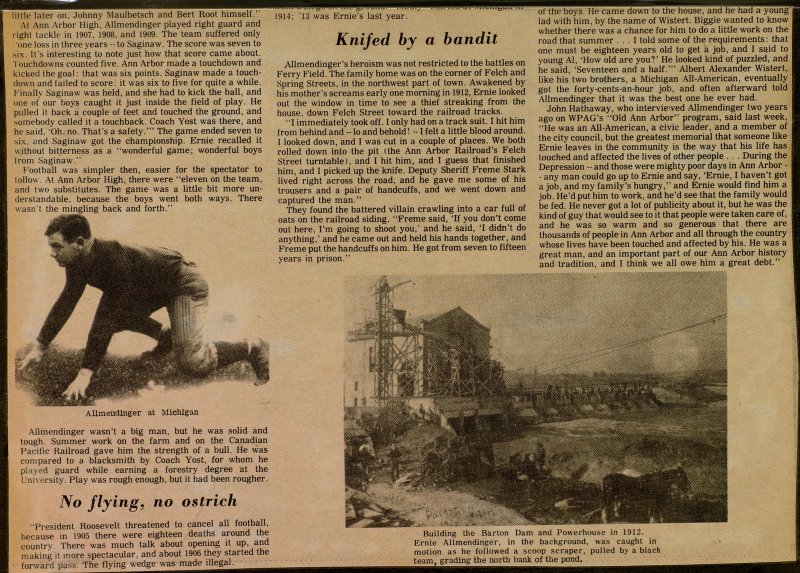

The death of Ernie Allmendinger on May 7 removed a giant from our midst. His passing was a shock despite his age. He had been with us so long he seemed immortal. He had become a legend in his own lifetime, a gridiron hero of the bright era -- now fading into myth - that Historian Howard Peckham has called "the Golden Age at Michigan." His strength, his cheer, his zest for life, had been learned early through hard work on his grandmother's farm and rough play on Ann Arbor's vacant lots. A non-smoker, he credited this and other good habits to the lessons taught in the football training camp of Coach Fielding "Hurry-up" Yost. i His humor was infectious. and his eyes twinkled when he had a good story to teil. Ernest John Allmendinger's long life began in Ann Arbor I on August 25. 1890. He was one of seven children of Henry and I ilhelmina Kraus Allmendinger, and he outlived them all. I His great grandfather, Daniel F. Allmendinger. who came in I 1829. was one of the first Germán settlers near Ann Arbor and I a founder oí the "'First Germán Evangelical Society of Scio," I to which he gave an acre of land as the site of the original I Zion Lutheran Church. built in 1834. It is the location of the I Uethlehem ('emetery on Jackson Road today. Tape recordings have luckily preserved some of the I colorful episodes of Ernie Allmendinger's career in his own I words. These anecdotes offer vivid glimpses of Ann Arbor in I times gone by. Aqua the waterboy An unusual nickname followed him through his life. As I Ernie told the story, it was first pinned on him when the Ann Arbor Kailroad began raising its tracks over Washington, I Huron. Miller and Felch streets in 1903. "There were I tremendous work crews on the trains that brought in the dirt, I which was plowed off. Most of the workmen on that project I were Italians, who couldn't speak any English. I was forI túnate enough to be the waterboy. I would come around with I the water, and the only thing they called out to me when they uanted some attention was 'Aqua! Aqua!" The name stuck, I reinlorced later by his own frequent calis for water during interludes in U-M football games. He won three varsity letters at Ann Arbor High School, but he had started playing the game even earlier, influenced by the glory that encircled the University's "point-a-minute" teams, beaten only once in Yost's first five seasons. "Quite a i lew of the local boys got started over on West Park. It was then Kohde's pasture land. Bert Root's older brother Fred .wis over there. and Mickev Milliman and Art Bell. and a "Yost used to say to us, 'Heads up - look ahead. You're not an ostrich. You gotta see what's coming towards you.' On tackles, everything was coming your way. You were supposed to expect it, and you were taught how to accept it, by playing low, by having a wonderful stance with your feet." Michigan was not in the Western Conference when Allmendinger played, choosing to withdraw for a decade rather than accept retroactive "reform" rules which hampered player eligibility and threatened Yost's career. As Ernie recalled, "Michigan went out of the conference in 1907, so our big games were Syracuse, Penn, and Cornell. I'll never forget that Pennsylvania team. We got beat. I can remember when we pulled into Ann Arbor, it was dark and cloudy and rainy, and "Brute" Pontius said, 'Even the olements are against us.'" Johnny Maulbetsch, like Allmendinger, earned the AllAmerica rating from Walter Camp. The two Ann Arbor lads "just grew up together. We started out in the old sand lots, all through high school together, till we were just about one." Then Maulbetsch left school for a year to work at a construction site on Main Street. Ernie recalled seeing him on the second floor of the steel framework, "catching hot rivets in the little nail barrel." The rivets were thrown up to him After graduating from Michigan, Allmendinger worked in ] western forests during the summers and coached football j here and elsewhere for a few years. Then the United States j was torpedoed into World War I. "I remember my pa telling J me one time, 'You know, if I was single, I'd enlist.' So I think 9 the next day I enlisted." He played football again, on the j Camp Sheridan team, and served in the infantry. In 1919 he ;j emerged a captain. In 1921, he married Marie Donohue, a Baltimore girl living ] in Adrián. Two daughters came to brighten their home. Also in 1921, he was hired as foreman by the Washtenaw Road j Commission, at a time when good roads were still a novelty. 3 "I was with the Road Commission about thirty-four years. 3 Then I followed by boss, Ken Hollenback, to the I Clinton Metropolitan Authority, and stayed with them until I retirement age. Hard work in hard times "I can remember, when I was working with the roads in the tough times in the 1930's, when they made the Dexter-Huron Park, the fellows were getting twenty-five cents an hour, and I they were loading the trucks by hand -- no machinery was I allowed." Some years later, "Biggie Munn worked at the University, I and he was getting little jobs for summer vacation for some I little later on, Johnny Maulbetsch and Bert Root himself." At Ann Arbor High, Allmendinger played right guard and righl tackle in 1907, 1908, and 1909. The team suffered only One loss in three years - to Saginaw. The score was seven to six. It's interesting to note just how that score came about. Touchdowns counted five. Ann Arbor made a touchdown and kicked the goal: that was six points. Saginaw made a touchdown and failed to score: it was six to five for quite a while. I Finally Saginaw was held, and she had to kick the ball, and one of our boys caught it just inside the field of play. He pulled it back a couple of feet and touched the ground, and somebody called it a touchback. Coach Yost was there, and he said. 'Oh. no. That's a safety.'" The game ended seven to six. and Saginaw got the championship. Ernie recalled it without bitterness as a "wonderful game; wonderful boys trom Saginaw." Football was simpler then, easier for the spectator to iollow. At Ann Arbor High, there were "eleven on the team, and two substitutes. The game was a little bit more un(ierstandable. because the boys went both ways. There vasn't the mingling back and forth." Allmendinger wasn't a big man, but he was solid and tough. Summer work on the farm and on the Canadian Pacific Railroad gave him the strength of a buil. He was compared to a blacksmith by Coach Yost, for whom he played guard while earning a forestry degree at the University. Play was rough enough, but it had been rougher. No flying. no ostrich "President Roosevelt threatened to cancel all football, because in 1905 there were eighteen deaths around the country There was much talk about opening it up, and making it more spectacular, and about 1906 they started the fnrwarri oass The flving wedge was made illegal. 1914; '13 was Ernie's last year. Knifed by a bandit Allmendinger's heroism was not restricted to the battles on Ferry Field. The family home was on the corner of Felch and Spring Streets, in the northwest part of town. Awakened by his mother's screams early one morning in 1912, Ernie looked out the window in time to see a thief streaking from the house, down Felch Street toward the railroad tracks. "I immediately took off. I only had on a track suit. I hit him from behind and -- lo and behold ! -- 1 feit a little blood around. I looked down, and I was cut in a couple of places. We both rolled down into the pit (the Ann Arbor Railroad's Felch Street turntable), and I hit him, and I guess that finished him, and I picked up the knife. Deputy Sheriff Freme Stark lived right across the road, and he gave me some of his trousers and a pair of handcuffs, and we went down and captured the man." They found the battered villain crawling into a car full of oats on the railroad siding. "Freme said, 'If you don't come out here, I'm going to shoot you,' and he said, 'I didn't do anything.' and he carne out and held his hands together, and Freme put the handcuffs on him. He got from seven to fifteen years in prison." of the boys. He came down to the house, and he had a young'l lad with him, by the name of Wistert. Biggie wanted to know I whether there was a chance for him to do a little work on the I road that summer ... I told some of the requirements : that I one must be eighteen years oíd to get a job, and I said to I young Al, 'How old are you?' He looked kind of puzzled, and I he said, 'Seventeen and a half.'" Albert Alexander Wistert, I like his two brothers, a Michigan All-American, eventually I got the forty-cents-an-hour job, and often afterward told 1 Allmendinger that it was the best one he ever had. John Hathaway, who interviewed Allmendinger two years I ago on WPAG's "Old Ann Arbor" program, said last week, I "He was an All-American, a civic leader, and a member of I the city council, but the greatest memorial that someone like I Ernie leavës in the community is the way that his life has i touched and affected the lives of other people . . . During the 1 Depression -- and those were mighty poor days in Ann Arbor - I - any man could go up to Ernie and say, 'Ernie, I haven't got I a job, and my family's hungry," and Ernie would find him a I job. He'd put him to work, and he'd see that the family would I be fed. He never got a lot of publicity about it, but he was the I kind of guy that would see to it that people were taken care of, I and he was so warm and so generous that there are I thousands of people in Ann Arbor and all through the country I whose lives have been touched and affected by his. He was a I great man, and an important part of our Ann Arbor history I and tradition, and I think we all owe him a great debt."