Yesterday

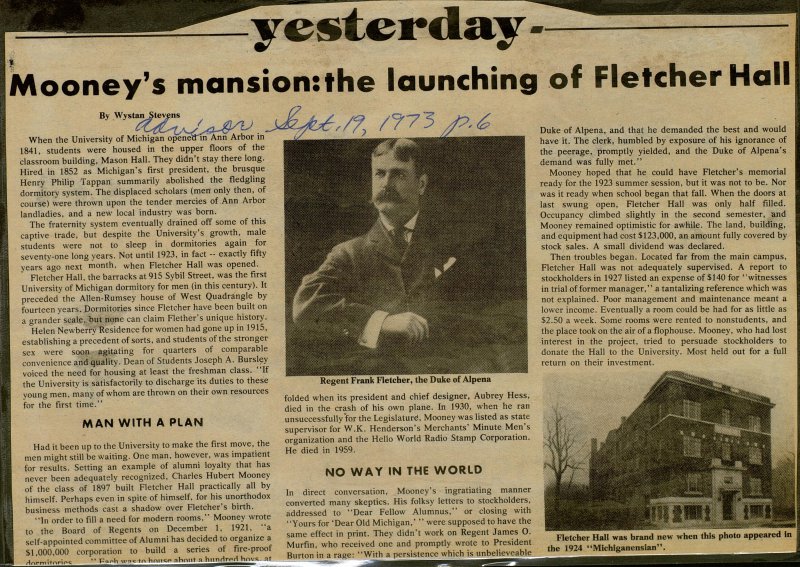

When the University of Michigan openetTÍn Ann Arbor in 1841, students were housed in the upper floors of the classroom building, Mason Hall. They didn't stay there long. Hired in 1852 as Michigan' s first president, the brusque Henry Philip Tappan summarily abolished the fledgling dormitory system. The displaced scholars (men only then, of course) were thrown upon the tender mercies of Ann Arbor landladies, and a new local industry was born. The fraternity system eventually drained off some of this captive trade, but despite the University's growth, male students were not to sleep in dormitories again for seventy-one long years. Not until 1923, in fact -- exactly fifty years ago next month. when Fletcher Hall was opened. Fletcher Hall, the barracks at 915 Sybil Street, was the first University of Michigan dormitory for men (in this century). It preceded the Allen-Rumsey house of West Quadrangle by fourteen years. Dormitories since Fletcher have been built on a grander scale.but none can claim Flether's unique history. Helen Newberry Residence for women had gone up in 1915, establishing a precedent of sorts, and students of the stronger sex were soon agitating for quarters of comparable convenience and quality. Dean of Students Joseph A. Bursley voiced the need for housing at least the freshman class. "If the University is satisfactorily to discharge its duties to these young men, many of whöm are thrown on their own resources for the first time." MAN WITH A PLAN Had it been up to the University to make the first move, the men might still be waiting. One man, however, was impatient for results. Setting an example of alumni loyalty that has never been adequately recognized, Charles Hubert Mooney of the class of 1897 built Fletcher Hall practically all by himself. Perhaps even in spite of himself, for his unorthodox business methods cast a shadow over Fletcher's birth. "In order to fill a need for modern rooms," Mooney wrote to the Board of Regents on December 1, 1921, "a self-appointed committee of Alumni has decided to organize a $1,000,000 Corporation to build a series of fire-proof ., ... ._ c„v, „,oe tn hnnsp ahniit a hiinrirpfi hrws. at folded when its president and chief designer, Aubrey Hess, died in the crash of his own plane. In 1930, when he ran unsuccessfullyfor the Legislaturé, Mooney was listed as state supervisor for W.K. Henderson's Merchants' Minute Men's organization and the Helio World Radio Stamp Corporation. He died in 1959. NO WAY IN THE WORLD In direct conversation, Mooney's ingratiating manner converted many skeptics. His folksy letters to stockholders, addressed to "Dear Fellow Alumnus," or closing with "Yours for 'Dear Oíd Michigan,' " were supposed to have the same effect in print. They didn't work on Regent James O. Murfin, who received one and promptly wrote to President Burton in a rage: "With a persistence which is unbelieveable Duke of Alpena, and that he demanded the best and would have it. The clerk, humbled by exposure of his ignorance of the peerage, promptly yielded, and the Duke of Alpena's demand was fully met." Mooney hoped that he could have Fletcher's memorial ready for the 1923 summer session, but it was not to be. Nor was it ready when school began that fall. When the doors at last swung open, Fletcher Hall was only half filled. Occupancy climbed slightly in the second semester, and Mooney remained optimistic for awhile. The land, building, and equipment had cost $123,000, an amount fully covered by stock sales. A small dividend was declared. Then troubles began. Located f ar from the main campus, Fletcher Hall was not adequately supervised. A report to stockholders in 1927 Usted an expense of $140 for "witnesses in trial of former manager," a tantalizing reference which was not explained. Poor management and maintenance meant a lower income. Eventually a room could be had for as little as $2.50 a week. Some rooms were rented to nonstudents, and the place took on the air of a flophouse. Mooney, who had lost interest in the project, tried to persuade stockholders to dónate the Hall to the University. Most held out for a full return on their investment. a cost of $4.50 to $6.00 per week per student. The pitch was aimed at other alumni, who would receive a seven per cent return on their investment. The stock would then be called in, and the property deeded to the University. The directors, to their credit, took no salary. Mooney quickly appointed sixty of the University's most prominent alumni to the corporation's advisory committee, a list heavily weighted toward judges, bankers, and the captains of industry. Governor Alex G. Groesbeck was on the list', along with Navy Secretary Edwin Denby. The names looked good on the letterhead, but few of the advisors were actively involved in the project. Mañy thought Mooney's i scheme was backed by the Alumni Association, an impression fostered by the large block "M" and blue ink on the corporation's yellow letterhead. Mooney had even thought of using the name "University of Michigan Dormitory Company," but settled for calling it The Dormitories Corporation. Pressure from the Regents and President Marión LeRoy Burton convinced him to drop the big "M," but he kept the yellow paper. Born in 1873, a large man with rimless spectacles, C.H. Mooney had had an interesting life since graduation. He spent some years in Columbus, Mississippi, as president of the New Dixie Lyceum Bureau, managing such diverse talents as the Chicago Glee Club, the Rounds Ladies Orchestra, and muckraking lecturer Jacob Riis. He sold insurance in Benton Harbor and Grand Rapids, then carne to Detroit to supervise a building company. He was manager of a branch of jfcoit's Commonwealth Federal Savings Bank when it wased of $30.000 of March 28. 1919. He later took a flyer onme Hess Aircraft Company, but that enterprise the circular instead of being addressed 'Fellow Stockholder' is addressed 'Brother Alumnus.' Apparently there is no way in the world of stopping this fellow." Mooney's tactics worked, and loyal alumni lined up to buy shares. Ground was broken for the first of ten contemplated buildings in October, 1922. $96,000 in stock had already been subscribed, of which $26,000 was paid in. The dormitory was designed by Rupert Koch, a local architect who also had offices in Muskegon and Detroit. Rupert was the son of John Koch, a partner in the Ann Arbor contracting firm of Koch Brothers, who put up most of the town's larger buildings in the early part of this century. While still in college in 1907, he supervised work on the Dental Building for his father. Prettyman's Boarding House stood near the construction site. "That is where my first notion of a men's dormitory was born," Rupert Koch wrote a few years ago. "I overheard men at that place, and from time to time in other of the rooming houses, (say) that they wished they could have better quarters where to live." Years iater in Detroit, Koch was called in to complete the Greystone Ballroom. "This and earlier buildings done by me brought be in contact with Mr. Mooney and so the dormitory idea was hatched." The building Koch designed contained three stories and a basement. 124 scholars were to be stuffed in doublé rooms on the upper floors, while a basement kitchen and dining room would be run by a concessionnaire. As it turned out, the rooms were too small and the food service went broke, but these practical realities did not intrude right away. After construction began, Mooney asked stockholders to suggest names for the building. None seemed satisfactory. Then on December 17, former Regent Frank Ward Fletcher of Alpena died at the age of 69. "The suggestion has been made," Mooney wrote to one of his trustees, "that it would be a fine tribute to pay his memory to name it after him for all i that he has done for the University in the first place and in the second place he was one of the first stockholders in the I Corporation and the first one to pass on to the Great Beyond." A regent for sixteen years, the vigorous Mr. Fletcher owned forests, lumber camps, paper milis and power plants in Alpena, where his words were usually received as commands. "He was not adept at taking advice," wrote former University Secretary Shirley Smith, with wry understatement. THE DUKE OF ALPENA Once, Smith recalled, Fletcher arrived "with a party of friends at the famous Shepheard's Hotel in Cairo, where he was met with the information that the best rooms, for which he asked, were not available. The Oxford accent and lofty bearing of the room clerk did nothing to soften the blow or to reconcile Fletcher to the news, and he persisted. Finally the clerk thought to clinch the argument by stating that the best accommodations were at üvery moment being held for a European count. That rP" the trigger! Mr. Fletcher poundcd on the desk, stated impressively that he was the RAIDED BY THE CÖPS "U. of M. HALL STUDENTS RUM SOURCE," blared the headline in the Detroit Free Press on November 4, 1929; "Raiders Seize Liquor in Dormitory that Alumni Built." The raid, which gained national notoriety, resulted in the arrest of two students on a charge of possession of "six quarts of bonded whisky and three quarts of apricot brandy," a serious infraction of the Prohibition laws. A third student, from Ontario, had eluded capture, slipping back to his native shore where possession of alcohol was not an extraditable offense. All three were expelled from the University. Newspaper stories revealed that the dormitory had been a bootleg distribution point. Those arrested were meeting college expenses by supplying liquor to several campus fraternities, as well as private buyers. The contraband was concealed in the attic, and calis requesting delivery were made in code. Outraged University officials ordered all students out of the building, the innocent with the guilty, effectively shutting it down for the rest of the term. The raid sounded the death knell for the Dormitories Corporation and its dreams. Soon the Depression closed in, and the directors were unable to pay the bonds and city taxes as they feil due. But C.H. Mooney's grand plan was realized after all, in a way. In 1933 the University acquired Fletcher Hall at a tax sale, for less than $13,000 -- almost a gift. Before his death in 1971, architect Rupert Koch put his own memories of Fletcher Hall on paper. That it had been built at all, he recalled, was "a surprise to many who did not think it would happen. I too had a feeling of satisfaction, that after I considerable of a struggle, it was completed. . . .1 might add I that, because of the type of construction, it will outlast many I similar buildings not so well built." It should stand for I another fifty years at least, a monument to a plan - and a man I - whose very failure was crowned with success.

Article

Subjects

Wystan Stevens

Ann Arbor News

Old News

Rupert W. Koch