Instinct to Play: Thollem McDonas at Kerrytown Concert House

by christopherporter

Thollem McDonas might be a compulsive collaborator. The American pianist, composer, keyboardist, songwriter, activist, teacher, and author's many projects have included several renowned, and lesser known, players over the years, and he doesn't seem to be slowing.

From improvisations with perennial experimental music headliners -- guitarist Nels Cline; double bassist William Parker; the late composer, accordionist, and electronic music pioneer Pauline Oliveros -- to his Italian agit-punk unit Tsigoti and the art-damaged spiel of the Hand to Man Band (also featuring American punk icon Mike Watt on bass and Deerhoof's John Dietrich on guitar), there's little ground McDonas hasn't covered or isn't covering. He might just be the ideal "six-degrees-of" candidate for people into that particular Venn diagram of weird improv, challenging chamber music, and thinking-people's punk rock.

McDonas plays Kerrytown Concert House on Friday, June 30, with a trio completed by two accomplished locals: reedman Piotr Michalowski and cellist Abby Alwin. We talked with the restless, and very thoughtful, pianist by email about his many collaborations, balancing political action with music, and sitting down at Claude Debussy's piano.

Q: You began playing piano at a very young age. What first drew you to the instrument, what are your earliest memories of playing, and when did you realize this is what you wanted to do in life?

A: My mom was a piano teacher and my dad played in piano bars. Some of my earliest memories were with the piano. I remember climbing inside my mom’s baby grand before I was old enough to start lessons. I was 13 when I kind of woke up one day and realized I had all these musical ideas. That composers were all people and that I was a people and I could be a composer. This is when I really made music mine for the first time. This is when I became obsessed.

Q: When did your interests begin expanding beyond your initial classical training?

A: I’ve always been curious about different approaches to music and what music means to people from different countries, cultures, and generations. I grew up in the San Francisco Bay area and turned 13 in 1980 when West Coast punk rock was in its heyday. When I was 12 my mom remarried and my step-sister worked at Kuumbwa Jazz Club in Santa Cruz. I started heading over there regularly and hearing some of the greatest innovators. I’ve always experimented; there really wasn’t a beginning to that. It’s more like there wasn’t an end, then a new beginning. Life is all about experimenting and playing with the world. We’re born with the instinct to play, the trick is not losing this in the first place.

Q: I read that you "decided to become homeless" for several years after college and "wander and live out of a backpack, rather than pursue a career as a concert pianist." Where all did you wander and what did you do? How did your parents take the news?

A: I didn’t know my dad so well, but my mom was pretty devastated. I quit everything during the build up to the Persian Gulf War. I didn’t want to circulate money or participate in society, and the idea of making a "career" in music, or anything else, seemed absurd. I lived with a backpack and sleeping bag, sleeping in all kinds of situations, from action centers to federal buildings to on the street. I traveled up and down and around the West. I burned a lot of bridges. In some ways, I wish I could’ve realized then that music was my best way to contribute (not that I have necessarily changed the world with my music either). It’s taken me a long time to figure some things out! But all those experiences are important parts of who I am and the work I’m doing now, both of which I feel good about, ultimately.

Q: Political action seems to be as important to you as musical exploration. When did you start to develop your political inclinations and what events and policies have shaped them over the years? How do music and politics intersect for you?

A: Learning to balance the two has been a constant struggle for me my whole life. I started with animal rights when I was in junior high school and that moved into environmental issues, then anti-war, then police brutality, institutional racism and the injustice system, and so on. Like I said earlier, the Gulf War was a big moment for me. I think we are really fucking things up (or allowing a few to), and it’s unfortunate because it’s so unnecessary. I don’t want to get preachy here, though. Estamos Ensemble and Tsigoti have both been specific outlets for me, at least in terms of expressing something larger than the music itself. And right now my partner, ACVilla, and I are in the middle of a three-year endeavor making audio/video experiences with the United States as a subject. We started it last year during the presidential campaigns, and it’ll culminate with the mid-term elections next year.

Q: Estamos Ensemble's mission is to encourage dialogue and collaboration around the U.S.-Mexico border. What made you take this up, and what has the response been since it started? Do you think most Americans really want a border wall, and what could change their minds?

A: I don’t know what most Americans really want. The border wall is cruel, and the security and private prisons and laws associated with it are Draconian. It’s the ultra-rich elite who are responsible for convincing people that poor people are their enemies. I think as artists we are in a special situation to bring people together and to share our common humanity. I started Estamos Ensemble in 2009, and we just released our third album (Suube Tube).

Q: What was it like to be invited to perform Debussy's works on his own piano and then to actually do it?

A: It was pretty amazing all around. The city of Brive-la-Gaillarde sent me a very official document, signed by all the city council members. It was only the second concert they had had with his piano since it had been found and semi-restored. It wouldn’t have been possible to pack more people into the room where the piano is normally on display. I could really feel the audience. And to play Debussy’s music, as well as my own, on his piano, to hear his music from that same vantage point as when he wrote this music originally -- pretty crazy! The first half of the concert I played pieces he had written on that piano. For the second half, I had invited the great contrabassist Stefano Scodanibbio to join me in structured improvisations I created specifically for us for this occasion. The recordings were released on Die Schachtel, out of Italy, and were the first recordings ever published of Debussy’s piano.

Q: Molecular Affinity, your album with Pauline Oliveros and Nels Cline, came out the month after she died late last year. What led to those sessions and what were they like to take part in? Was there any thought given to this possibly being some of the last music she recorded and released?

A: No, I think most everyone thought she was going to be around for a while. She still had so much energy right up until the end, working on an opera and so many other projects. This was the third trio album Nels and I recorded together, each time with a different third member (William Parker on the first, Michael Wimberly on the second), and we asked Pauline if she’d be into it, and she was. We had a great time before, during, and after the session. Pauline was always a real joy to be around, and Nels and I are good friends. So it was a pretty relaxed time making music together in an old renovated barn in upstate New York. Pauline suggested this studio because Daniel Weintraub, the main engineer, is making a documentary about her. She was working on it with him. Fortunately she was, and now Daniel just has to follow through with what their general plan was.

Q: You've done three albums now with Cline. How did you two come together and what makes him a good recording partner for you?

A: I heard Nels and Thurston Moore play and had an idea for a duo with Nels where he’d play melodies through feedback in response to the harmonics I’d bring out of the piano with these hyper speed clusters. He was into it. Then I thought to invite William Parker to play as a conduit between us. When we recorded, we used these relationships as leaping off and landing points. For the second album, we were both involved with Analog Outfitters out of Urbana, who repurpose parts from old Hammond organs, and I thought it would be interesting to see what might happen with all this equipment. Nels is a really interesting person to me and an incredible musician who has always been exceptionally curious, diving into many different approaches over the years.

Q: How did the Hand to Man Band come to be and how was jamming with Mike Watt? Were The Minutemen a group you followed as a Bay-area teenager?

A: The Minutemen were playing when I was just coming of age, so they definitely had a big influence on me. Punk is what we make it and “start your own band” are about two of the most influential statements I’ve ever heard. Watt is an incredibly intense person. Definitely one of the smartest people I’ve ever known. A crazy memory for all kinds of subjects throughout time, including who played in what band and seemingly every single gig he’s ever played. He’s a fan of Tsigoti. John Dieterich (of Deerhoof) and I were invited to record at Nicholas Taplin’s studio, which was in Austin at the time. So, I thought to invite Watt and John invited Tim Barnes. We made a second album as well but decided not to release it.

Q: Tsigoti is something very different from your solo and improvised work, and also different for punk rock -- even at its more adventurous -- since you don't often hear acoustic piano in the genre. It makes me think of The Minutemen and maybe The Ex a little. How did the group start and what does this project let you do that your many others don’t?

A: Tsigoti was started on a whim in a musician's house in the hills of Tuscany. I had been at this house for a while and with three days left, me and Andrea Caprara and Matteo Benicci and Jacopo Andreini decided to make a punk album. I had pages of words I had spent a week writing while I was in Prague about the war between Israel and Lebanon, and we turned these into songs. The whole idea was to write songs in the studio, recording them in less than three takes, mix and master before I left. We’re now working on our fifth album. We did a U.S. tour a while back and a bunch of Italian/European tours, including an anti-mafia tour throughout the country in association with anti-mafia groups there. We’ll probably play some shows in Italy next summer.

Q: For this Ann Arbor show, you're playing with a local mainstay in free improv in Piotr Michalowski and also Abby Alwin, the orchestra director for Ann Arbor Public Schools. Have the three of you ever played together before? What can people expect?

A: We’ve all played together in one way or another, though never as a trio. We’ll be playing structured and freely improvised music. It will go in many different directions, exploring all the many different possibilities our instruments are capable of. Solos, duos, trios, extended techniques. I’m sure there will be many very abstract sonic moments as well as modal/melodic playing. Abby and Piotr are both amazing musicians, so it’s going to be amazing. What else is there to say?

Eric Gallippo is an Ypsilanti-based freelance writer and a regular contributor to Concentrate Ann Arbor.

Thollem McDonas Trio plays Kerrytown Concert House, 415 N. 4th Ave., Ann Arbor, on Friday, June 30, at 8 pm. Tickets are $5-$30. Visit kerrytownconcerthouse.com for more info.

Korde Arrington Tuttle and The National's Bryce Dessner examine photographer Robert Mapplethorpe's work through song in "Triptych (Eyes of One on Another)"

by christopherporter

By the time the singers, musicians, and iconoclastic images of photographer Robert Mapplethorpe take the stage at Ann Arbor's Power Center on Friday, March 15, everything should be in place for the premiere of a new UMS-commissioned work examining the late photographer's work and legacy through song.

Edgefest & Piotr Michalowski have helped make A2 a haven for avant jazz

by christopherporter

As free-jazz hero Joe McPhee got started on the third movement of Tuesday night's Fringe at the Edge concert at Encore Records, he settled into a minimalist, two-beat groove that was sometimes barely audible.

While McPhee patted his palm against the mouthpiece of his pocket trumpet, drummer Andrew Drury fell in, lightly tapping skins, rims, and cymbals for a nervous, anti-beat.

Piotr Michalowski held his sopranino saxophone and listened a moment, then completed the percussive theme by popping and puffing through his horn, before the trio opened up into long-toned exuberance. When it was over, Drury made Michalowski jump and then grin, as he frantically bowed away at some metal for a screeching effect.

Announcing the band members between numbers, Edgefest organizer Deanna Relyea shared that the visiting McPhee and Drury would be up early Wednesday morning to teach music students at Scarlett Middle School. Ann Arborite Michalowski, Relyea's husband, would be up early too, she joked: "To clean the house."

If you've followed jazz or improvisational music in Ann Arbor at all for the last 20 or 30 years, you've probably run into, read something by, or seen and heard some mind-expanding reed work by Michalowski.

The improv-music-scene staple is a regular face at Kerrytown Concert House's avant-garde Edge events, including its annual Edgefest, which returns this week for the 21st edition (Oct. 18-21), where he also often plays as a scheduled performer or sits in with visiting musicians. He also writes a monthly music column for the Ann Arbor Observer.

While he can hang with players like Drury and McPhee ("Joe McPhee, you know, is God," he says), Michalowski, makes it clear he's a hobbyist when talking about his own music -- "a palette cleanser" from the academic rigor of his previous 9 to 5 as a professor of Near Eastern Studies at the University of Michigan.

Other than a few masterclasses on extended techniques, Michalowski is self-taught. He's played several reed instruments over the years, eventually focusing on bass clarinet, but baritone and soprano saxophone and sopranino are often in the mix.

"I guess I have the Vinny Golia disease, so that I'm a multi-instrumentalist," he says. "I don't really have a main horn."

Michalowski grew up in Poland and moved to the United States in 1968 to earn his master's degree and Ph.D. at Yale University. After postgraduate research at Harvard and Penn, he took his first job at UCLA.

He'd been an avid jazz fan since he was a teenager -- he swore off rock 'n' roll after seeing the Jazz on a Summer's Day concert film -- but his tastes leaned more toward the old school, New Orleans-style than the new avant-garde.

In Los Angeles, Michalowski made friends with a record-store clerk who turned him onto some further-out sounds, including L.A. players the clerk also booked at the storied Century City Playhouse. There, Michalowski checked out gigs by adventurous improvisers, like John Carter, Nels Cline, and Golia, the last of whom inspired him to start playing clarinet.

"It was a fantastic scene," he says.

After a stint teaching in Philadelphia during which he didn't really play, Michalowski landed in Ann Arbor in the early '80s to work at the University of Michigan, where he continued to teach until just last year.

He took up music again at the urging of a friend and was soon playing traditional jazz, swing, and standards on alto and tenor sax, performing with David Swain's II-V-I Orchestra and jams with friends. He enjoyed the tunes, but it didn't feel right.

"I was playing 'Body and Soul' at some art place, and I just thought, 'It's totally ridiculous for me to play "Body and Soul."' I have in my head Coleman Hawkins and all these classic performers. It's almost sacrilegious for me to do it. While I love listening to that music, playing it was absurd. You could say playing as an amateur is absurd anyway, but I love doing it. That was just so crazy. I decided I was just making an ass of myself, and I just couldn't really justify it."

So, in the '90s, he turned back to his love of improvisation and found some like-minded, younger players at the University of Michigan and its Creative Arts Orchestra, who he started sitting in with. He collaborated regularly with James Ilgenfritz, Sarah Weaver, and "a whole generation" of musicians until they eventually left town to pursue their music.

Another longstanding collaborator for years was Detroit violinist Mike Khoury, with whom Michalowski has released a half-dozen or so short-run CDs. He's also continued to play with Ilgenfritz when the two are in the same city. In March, the two played as an impromptu trio with U-M music professor Stephen Rush during an Ilgenfritz show at Kerrytown Concert House, and earlier this month, Michalowski and Relyea, a mezzo-soprano vocalist, joined the bassist in Steve Swell's band for a New York performance.

Through Kerrytown and Detroit's free improvisation scene, Michalowski has made connections around the country that have developed into mini-tours with professional musicians and one-off shows in other cities when traveling for work.

He recalls one notable house show in Berkley, Calif., wiith Golia and Jon Raskin of the Rova Saxophone Quartet all playing sopraninos. "It was advertised as a very squeaky evening," he says.

When pianist Thollem McDonas was recruiting musicians to perform with at Kerrytown last summer, he asked Michalowski and Ann Arbor cellist Abigail Alwin to join him. McDonas recorded the session, which is now posted to Bandcamp as part of a 15-album series produced while touring.

"Piotr is such a joyful person, and it overflows into his playing," McDonas says. "He moves seamlessly from one instrument to another. (He has) profound respect for his fellow musicians (and) giant ears. He allows much space for others, (and) he can jump head first into any texture and dynamic."

Using those "giant ears" is a big part of the music's appeal for Michalowski.

"One of the great things about this music is it's truly in the moment and it's always collaborative in the sense you really have to listen," he says. "You're always sort of balancing. You're on top of a ball on one foot. You can always fall off and do something that's egregiously wrong."

While other forms of jazz and new music have made an art of working through complex harmonies, free improvisation, puts the focus on sound and timbre.

"When you're playing a reed instrument, it's an extension of your body, and you immerse yourself in these overtones and this sound and discover new ways of doing that," he says. "It's very intuitive."

He tells a story about avant-garde saxophonist Evan Parker leading a workshop where he told musicians to "make your entrance" count. It's something that's stuck with him over the years, and he's seen great players, like McPhee, do countless times by hanging back, listening, and then taking the music into a totally new direction.

"Good musicians will pick it up and move it," he says. "You have to pick up the cue immediately. When you get on the stand, you can't coast."

Eric Gallippo is an Ypsilanti-based freelance writer and a regular contributor to Concentrate Ann Arbor.

The 21st annual Edgefest is based out of Kerrytown Concert House, 415 N. 4th Ave., Oct. 18-21. For tickets, more info, and visit kerrytownconcerthouse.com.

All the shows listed below are at the Concert House unless otherwise noted:

Wed. 10/18, 6:00 pm - Mike Gould, Malcolm Tulip, Deanna Relyea, Katri Ervamaa

Wed. 10/18, 7 pm - Trombone Insurgency

Wed. 10/18, 9 pm - Pheeroan akLaff: aRT Trio

Thu. 10/19, 6 pm - Jonathan Taylor Quintet: Mover

Thu. 10/19, 7 pm - William Hooker Duo featuring Michael Malis

Thu. 10/19, 8 pm - Joseph Daley Tuba Trio

Thu. 10/19, 9 pm - Allison Miller’s Boom Tic Boom

Fri. 10/20, 6 pm - Ben Goldberg’s Invisible Guy

Fri. 10/20, 7 pm - Tom Rainey Trio

Fri. 10/20, 8 pm - Andrew Drury’s Content Provider

Fri. 10/20, 9 pm - Larry Ochs Fictive Five

Fri. 10/20, 9 pm - Tristan Cappel Quartet (free, Sweetwater's in Kerrytown)

Sat. 10/21, 12 pm - Edgefest Parade (free, Ann Arbor Farmers' Market)

Sat. 10/21, 2 pm - Gayelynn McKinney & Ken Kozora "> Oluyemi Thomas Trio

Sat. 10/21, 4 pm - Steve Swell’s Soul Travelers

Sat. 10/21, 5:30 pm - Matt Daher Duo (free, Amadeus Restaurant)

Sat. 10/21, 7:30 pm - Andrew Drury/Edgefest Ensembles (Bethlehem United Church of Christ)

Sat. 10/21, 9 pm - Adam Rudolph’s Moving Picture with Hamid Drake

Sat. 10/21, 10 pm - Tomas Fujiwara’s Triple Double

Flexible & Free: Dave Rempis' Ballister at Kerrytown Concert House

by christopherporter

Saxophonist Dave Rempis has fond memories of playing Ann Arbor over the years. The Chicago-based improviser and long-time member of renowned free jazz group The Vandermark 5 fondly recalls late-'90s gigs with locally grown and trained players, such as Colin Stetson, Stuart Bogie, and Matt Bauder.

But none were likely more memorable than a workshop for students at the University of Michigan School of Music, where Rempis had applied and been rejected a few years earlier.

"I totally flubbed my audition with a classical saxophone teacher, so he said, 'Why don't you go play for the jazz guy next door?'" Rempis says. "So, I went over there, and I'm not sure how well that went. I didn't get into the University of Michigan, and my first gig on tour with The Vandermark 5 was doing a workshop in the same professor's classroom. So that was my first paying gig out of college. I thought that was kind of funny."

After ditching classical sax for ethnomusicology at Northwestern University, Rempis dove into the Chicago music scene after graduation, where he became a vital part of not only its storied free jazz and improvisational music circles as a musician and presenter, but also indie rock community as an events coordinator and, eventually, business manager of the Pitchfork Music Festival.

Today Rempis plays with several improvisational music groups as well as solo, and he also serves as board president of the Elastic Arts Foundation and operations manager for the Hyde Park Jazz Festival. On Saturday, he returns to Kerrytown Concert House with Ballister, his hard-charging trio with cellist Fred Lonberg-Holm and drummer Paal Nilssen-Love.

We spoke with the affable reedman by phone from Chicago, where, in addition to his music, he took the time to talk with us about "nerding out over spreadsheets," perpetual pre-show jitters, and the enduring work ethic of the late, great Fred Anderson].

Q: How did you get started in music?

A: I started playing when I was 8. My father’s Greek, and we had a family friend that played in Greek bands around town. I would see him play at weddings and stuff, and I was totally fascinated. My brother started playing clarinet pretty young, and as soon as he started that, I was like, “I want to play the saxophone.” In high school, I was lucky to play with a small jazz group at a local music school. A lot of kids were focusing on playing big-band charts and not a lot of improvising, but I really got the opportunity to play jazz tunes and improvise on them, which was an incredible puzzle. It was just a really interesting set of musical and other challenges, and I just totally got hooked on it.

Q: I read that you went to Northwestern to study music before switching to ethnomusicology.

A: I was young and I didn't know what I was getting into, so I applied for a classical saxophone program to get my technical chops together. As soon as I got there I realized this was the most soul-sucking thing I could possibly do to myself. Just hearing saxophone players in practice rooms for eight hours a day playing exercises without any musical conclusion. It was like gymnastics.

I was lucky my first semester to take a class with a musicologist who did a lot of work in Zimbabwe. He also wrote a big book on jazz improvisation. That class just kind of blew my mind. I was playing and maintaining my jazz interest, but by junior year of college, I decided to study in Ghana for a year in West Africa, which was totally incredible and very much connected to the interest I had in jazz.

Q: Out of college you were asked to join The Vandermark 5. How did that happen?

A: I'd met [bandleader] Ken [Vandermark] a few times, and when I got out of school I decided I wanted to play. My plan was to work a day job and practice as much as I could and see what kind of opportunities I could find around town. I went to a show at The Velvet Lounge one night, and I asked Ken if I could take some lessons with him on extended techniques he and others were doing. So I took a couple of lessons with him, and that fall, in 1997, Mars Williams decided to leave the band. Ken called me in November or December and said, "Mars is leaving the Five, and I'd like you to come audition for the band."

Q: Did you get a sense at that time that things were picking up there? It sounds like there was a lot of energy and excitement around that scene of music.

A: It was incredible. There had been so much happening in Chicago for a long time, and I think in the '80s a lot of the energy dissipated. But in the early '90s, there was sort of this convergence of forces. Ken is one of the people who really did a lot of work to build an infrastructure for the scene. He started this series at The Lunar Cabaret, and then he started The Empty Bottle series in 1995, and those things started to have a lot of resonance.

Around the same time, Fred Anderson had been running The Velvet Lounge for a while, but I think he was just running it as a bar and then eventually started doing music there in the early-mid '90s.

So this momentum started to happen, and it was a combination of local musicians doing more and people coming in from out of town. Fred [would] play at the Velvet all the time. I remember seeing Steve Lacy play down there with his trio, Milford Graves at The Empty Bottle, a lot of European improvisers at The Empty Bottle through its festival, Joe McPhee.

All these people started coming back to Chicago, and it was a regular occurrence in the late '90s that you can go see incredible people twice a week visiting from out of town. That helped really create this exchange with what was happening in Chicago and what was happening all over the world that is still sustained. Now it feels like it's been here a long time. We almost take it for granted. But at that point, it was something that was just emerging again, so there was a lot of excitement around it.

Q: I love that idea of Fred playing his own club a couple of times a week -- that you could just go and watch him play whenever you wanted.

A: Totally. You could go down the Velvet, and he'd be sitting there working the door. Somebody, it might have been Ken, wrote some liner notes about Fred sitting in on the second set with a band and then walking off stage to fill up the cigarette machine. That's still a work ethic and a mentality that informs the way a lot of venues here are run.

Q: How long were you working on Pitchfork Festival, and how did that come about?

A: I helped start it in 2005 and just left last fall. Mike Reed is a drummer in Chicago who founded the Pitchfork Music Festival. I started bartending right out of college, working at a small jazz club called the Bop Shop and then started working for a couple of different larger rock venues owned by the same company, so I’ve always kind of been involved in front of house type stuff in venues.

I had a lot of large concert concessions experience and had also worked a number of outdoor events for those folks. So when Mike started the festival, he asked me to come on as the concessions manager in the first year for what turned out to be a pretty large operation. The second year he split up with his partners on the event and asked me to come in and basically take over a lot of the logistical organizing type stuff on the event.

Q: Is logistics something you enjoy, or is it more about community enrichment?

Q: I guess kind of enjoy it. I’m a very detail-oriented person. I would love to just focus on music, but the stuff that goes into making sure music happens is a huge factor in making sure I and others have the opportunity to present our work. I do those things more out of necessity than desire, but at the same time, I can definitely nerd out over some spreadsheets.

That translates on a lot other levels. We’ve both been organizing jazz and improvised music events in Chicago for a long time. I’ve been booking a Thursday night series here at the Elastic Arts Foundation since 2002, where I'm now board president. We’re doing four-to-six concerts a week as a small not-for-profit venue without a bar.

Q: Being a working musician on the road, you probably get a lot of ideas about how to run a space like that.

A: Totally. I did a solo tour last spring and part of the idea was to work on solo material and approaches, but going on the road by myself, I was able to go to a lot of different places I wouldn’t take a band, much of it for financial reasons. I did 31 concerts in 27 cities in the States. There are so many things happening, and sharing that information and learning from other people about how they’re approaching this kind of stuff, about how they fund it, how they organize it, who’s doing it, all that kind of stuff is really valuable, and I think a big part of what we do as touring musicians is actually helping to create and sustain those networks.

Q: What sets Ballister apart from your other groups?

A: Part of what I like is the flexibility of it. In a way, it's the instrumentation and the skills of these particular musicians, and a lot of it comes down to Fred, who's a cellist who just has this incredibly wide palette. He can interact more like a bass player might, playing a vamp or something, or he can interact the way a guitar player might, playing more melodic things. He can interact the way an electronics musician might, with a lot of screeching noise-type stuff, and he's great at all those things.

Paal is somebody who's out playing 250 to 300 concerts a year on the road. I can't quite imagine living that life, but he's somebody who shows up to every single gig and is totally committed to it.

On a personal level, it's just a bunch of guys who really enjoy playing music and are really passionate about life and just put a lot of energy into the whole thing.

Q: What mindset does playing with those two put you in? What does it let you explore that you can't with other groups?

A: It can be a pretty loud group at times, and I'm really enjoying exploring those limits of how far can I push myself physically. That on its own can lead to new things musically. And in a lot of ways, it ties to the music I was interested in and studying. Ideas of spirit possession, in a way, for example. Or you listen to Coltrane in his later period, and he's so focused and energetic and pouring all this physicality into his instrument. That type of thing really stands out to me listening to it but also playing it, how that feels. It's almost like an athletic thing, to push yourself to these boundaries. I just think you get to new places by doing that.

Q: Is anything charted at all beforehand, even in a basic way? Some of the recordings have some very composed sounding parts.

A: It's all purely improvised. We've never written a chart or came up with a game plan of how we're gonna start or structure a piece or anything. It's all open.

To me, one of the "goals," so-to-speak, is to create music that sounds like music and doesn't just sound like three people playing together randomly. Improvised music that speaks to me does feel as composed as what you might say composed music sounds like. And that's what I think makes for a good performance is when that feeling is there, of, "We know where this is going." There's no question. If the musicians feel that question and aren't sure where it's going, then you hear that.

Q: Do you still have a feeling before you start, of, "OK, let's see what happens?"

A: Definitely. I get nervous right before I start, just in the sense of, "What are we gonna do? Is this gonna work?" You know, we don't have anything to fall back on. This could be a trainwreck (laughs). I think that fear never quite goes away, but then you get on stage and start playing and you realize, "Oh, no, it's gonna be OK."

Q: You started Aerophonic Records a few years ago with a vision to control your body of work and not use streaming services. How's that going and how are you feeling about it today?

A: It's a lot of work, but it's one of the best decisions I've ever made. It's allowed me in so many ways to connect with my audience. I have email conversations with the people who buy my records who live all around the world. There are so few labels at this point putting out this kind of music, it's really kind of a blessing to not have to wait for them to approve a project. As long as I'm able to plan out my schedule, I can release whatever I want, whenever I want. That's very liberating in terms of trying to coordinate schedules around when a band can tour, my own personal schedule, all that kind of stuff.

Q: How did the refugee benefit album you did come about and what was the response like?

A: [Pianist] Matt Piet called [drummer Tim Daisy and I] up to say, "Do you guys want to do a session?" in the fall of 2016, so we said, "Yeah, sure." It ended up being on the day after the election. All three of us were basically in a state of shellshock. We just got together to play, and afterward we said, "We should do something with this around inauguration time." We ended up doing a benefit for Planned Parenthood the Saturday after the inauguration. It was a really nice triple bill at Elastic Arts. The room was packed, and we raised a ton of money for Planned Parenthood, and the set just felt really great, and it tapped into the positive energy that day from the Women's March because the concert ended up being a kind of after party for that.

It just had a really special feeling to it. I think that's a great record, and I'm really proud of it, and we were able to raise about $500 for Refugee One, which is a local Chicago group that helps resettle people in the United States from various parts of the world.

Eric Gallippo is an Ypsilanti-based freelance writer and a regular contributor to Concentrate Ann Arbor.

Dave Rempis' Ballister plays Kerrytown Concert House on Saturday, Sept. 30, 7:59 pm. For tickets and more info, visit kerrytownconcerthouse.com.

Slow Burner: Alabama Slim at the Ann Arbor Blues Festival

by christopherporter

In addition to the impossible-to-replicate lineup, the real legacy of the original 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival is in how a group of college students helped introduce mainstream, white America to the incredible music being overlooked all around it for years in favor of repackaged versions from the U.K.

If there's such a secret hiding in plain sight at this year's revived Ann Arbor Blues Festival, it's probably Alabama Slim. Born Milton Frazier in Vance, Alabama, Slim didn't record an album until he was in his 60s, when he finally teamed up with his cousin, fellow New Orleans guitarist Little Freddie King (not to be confused with the late Chicago guitar great Freddie King) to record The Mighty Flood for the Music Maker Relief Foundation.

Slim's a first-rate storyteller, whose warm baritone voice and tasteful, hypnotic playing recall all-time greats, like Muddy Waters or John Lee Hooker on a slow burner.

We talked to Slim briefly by phone on the eve of a family reunion in Birmingham, Alabama, where he was looking forward to some good food, drinking a couple of beers, and relaxing after a long drive.

Q: How did you get started playing the blues?

A: My mother had a Victrola. You know, one of those Victrolas with the little dog looking down the horn? We had this record of Big Bill Broonzy: "Mean Old Frisco," and I liked it, and I fell in love with it. And then I heard Lightnin' Hopkins and Muddy Waters and different ones, and I said, "Aww, man. I wanna play."

When I was about 11 or 12 years old, a guy across the district, you know, we lived in the country, he had a guitar and he would come over and play, and I would get his guitar and start strumming on it and strumming on it. And he said, "This boy's gonna play one day."

So somehow my uncle got a guitar. I think he paid $10 or $12 for it. I started blummin on it, you know, "blum, blum, blum," and my fingers and my thumb got swollen up. I had to soak them in salt water and all that stuff.

So one day, I played this record by Lightnin' Hopkins, "Rocky Mountain." And after that, I played this Bill Broonzy record, and I was like, "Aww, shucks. I got it goin' now."

Q: When did you start playing out?

A: We were going to school, and we had three or four cats that were wannabe musicians: piano, horn. So we'd get together and play. People would get us, you know, out in the country where we had that whiskey drinking and home cooking going on. They'd say, "You boys come over and play for us." We'd go over there and play, and good God almighty, they'd give us about $10 a piece, and that was a whole lot of money then.

Q: How old were you when you're playing these parties?

A: About 18 or 19. After that I started running a little wild. You know how it is with them girls, man, and taking a little taste of that liquor and going on, you know. So I put it down, and I come back at it again, and I put it down. So when I came back this time, I stayed with it.

Q: You didn't record an album until later on in life, is that right?

A: I recorded an album in 2006.

Q: But before that you hadn't made any recordings?

A: No, I hadn't done any recordings. Just playing around with this band, that band. I'd get me a couple of guys and we'd play around and that. But after Katrina hit in 2005, then I made that CD, The Mighty Flood

My cousin Little Freddie King, me and him would jam around. He had a 335 Epiphone guitar, and he said, "I know you can handle it." So I got to playing with him and going around. His manager, he was crazy. He didn't want me being with Freddie. So, after Katrina hit, me and Freddie went to Baltimore. I was supposed to play a couple of numbers, but Freddie's manager made sure I didn't get a chance to play. So I told Tim Duffy (founder of the Music Maker Relief Foundation), and that kind of made Tim a little mad. He said, "I tell you what: when you get ready to cut a CD, you call me," and he gave me his card and said, "My secretary will set it up." And so I did. I went and cut that CD The Mighty Flood with Freddie, and I've been rolling ever since. I've been all different places: Germany and Scotland. I go all over. Everything's going sweet and good now.

Q: Do you feel like you're making up for lost time?

A: Yeah, I am. Really, I am. I'm catching up, and this music keeps me going. I'm 78 years old now. This music is keeping me going. You know, I'd be sitting around or something, I'd probably be real down. When I play my guitar, I feel like I'm 16 years old.

Q: So when you were "putting it down and picking it up again," what were you doing for a living?

A: I always kept a job. Some of the jobs were really rough. Working at a sawmill, doing coal mining, digging ditches, and whatever. When I got to New Orleans in '65, that's where I stayed. I got a job at the World Trade Center of New Orleans. I worked there 24 years. I was a porter there. In other words, a maintenance man. When they had parties and things, that's when I really made my big money. That was a nice job. And I had my little band going, and we were doing pretty good.

Q: You have a distinct style we don't hear as much today. I saw someone describe it in a YouTube comment as "Blues with possibly the fewest notes." It was a compliment, and I agree. Where did that style come from, and is that something you're conscious of?

A: The blues tells a story, because the real blues is the problems that you have and things that you're going through. That's real blues: heartache, or something that you want, you can't get it; or you think you can get it, but you're like, "Why can't I get it?" So you've got the blues.

And then if you love someone and something's going wrong and your woman quits you or something, man, you've really got the blues!

Q: I'm thinking about the sound. There's a tendency in newer groups to focus on big solos. When I listen to you and watch you with the band, it's like everything just fits together.

A: Right. You know, a lot of guys come out here today and talk about playing the blues, but their set will be halfway blues and halfway rockin' stuff. But the real blues, you just can't get around it.

Q: That heartache, it really comes through in your songs, and you're telling these stories about "The Mighty Flood" and "Crack Alley." Are these real experiences you've lived through?

A: Yeah, man! I been through that stuff. I'm serious. It's funny, I hooked up with a girl, and I really didn't know at the time, and then I found out she was addicted to crack, and I had to cut her loose. And I was in the flood. I saw it.

Q: Are you living in New Orleans now?

A: Yeah, that's where I live right now. When the flood hit, I went to Dallas, because my wife has two sisters out there. So me and Little Freddie and my wife went there and stayed about 14 months, then I came back to New Orleans.

Q: When you were in Dallas, is that when you started thinking about making the first album?

A: That's when I put it together. Sure did. I was devastated with that Katrina. Water everywhere. Oh, my God. If you listen to the record real good, I tell the whole story of it.

It's kind of amazing how something so disruptive gave you an opportunity you might never have had.

That's right.

Related:

➥ Resurrected: James Partridge on the 2017 Ann Arbor Blues Festival

➥ Put a Spell on You: Michael Erlewine on the 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival

Eric Gallippo is an Ypsilanti-based freelance writer and a regular contributor to Concentrate Ann Arbor.

Alabama Slim plays the Ann Arbor Blues Festival at 2 pm on Saturday, August 19, at the Washtenaw Farm Council Fairgrounds, 5055 Ann Arbor-Saline Road, in Ann Arbor. The whole event runs from 1-11 pm and advance tickets are $35 ($17.50 for kids age 13-18, free for kids 12 and younger). For tickets and more info, visit a2bluesfestival.com.

Resurrected: James Partridge on the 2017 Ann Arbor Blues Festival

by christopherporter

As an East Coast transplant and late-comer to the blues, you can forgive James Partridge for not knowing Ann Arbor's storied history with the world's greatest blues musicians until fairly recently (or exactly blame him -- there's no Beale Street or other marker to speak of).

But as founder of the recently formed Ann Arbor Blues Society and co-organizer behind the return of the Ann Arbor Blues Festival, which takes place Saturday, August 19, at Washtenaw Farm Council Fairgrounds, he's making up for lost time quickly.

Partridge was turned on to the blues by a guitar teacher while taking lessons as an adult and was soon thinking of ways to get more live blues into his life on a regular basis locally.

When he started doing his homework, he soon learned he was basically living in the birthplace of the electric blues festival.

"I started doing some research and was like, 'Whoa!" he says. "Not only did Ann Arbor have blues festivals here years ago, but we invented the blues festival for crying out loud. I couldn't believe that."

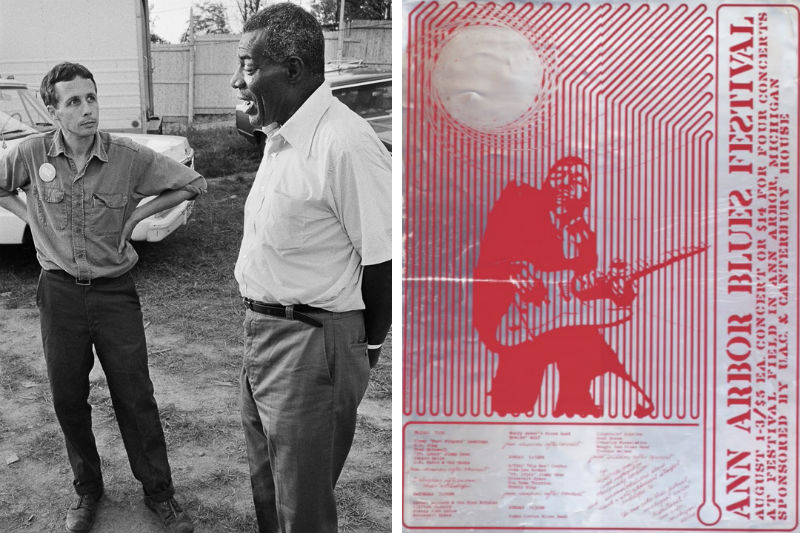

The original 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival is believed by many to be the first and greatest of its kind, with headliners including just about any name a casual blues fan could think of -- B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Son House, Big Mama Thornton, Otis Rush.

The follow-up event in 1970 was a close second, and after taking a year off, the festival returned in 1972 under new management as the Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival. Under the direction of John Sinclair, the fest expanded to include jazz giants, like Miles Davis and Sun Ra, before dying out a few years later. Another run of Blues and Jazz Festivals ran from the early '90s to mid-'00s with a slightly different format, ending in 2006.

With the 50th anniversary of the original Ann Arbor Blues Festival approaching, Partridge contacted several local event promoters and others in the music industry with the idea of trying to revive the fest in time to commemorate that milestone. When he didn't get any takers, he eventually decided to do it himself, thanks in part to the encouragement of co-organizer and local blues musician Chris Canas.

"The fact Ann Arbor had such a tremendous impact on the genre and on the lives of the musicians who played here and the people who organized it and the people who attended but nearly 50 years later it was like nobody knew that had happened except for a really small group of people was just startling," Partridge says. "I could not fathom that."

With the help of about a dozen volunteers, Partridge and Canas set to booking the venue and artists, securing sponsors, advertisers, and vendors, and promoting the festival. Thanks to a successful GoFundMe campaign, Partridge says attendees can expect a first-rate stage and sound system for the all-day event.

"We've done a significant amount of work in a very short period of time," Partridge says. "Far more than most people ever thought possible. I thought we would need a year of planning, and we put it together in like four months."

Partridge hopes to get at least 1,000 people out for this first "dress-rehearsal" festival Saturday, with his on eye substantially growing the festival each year from there.

"We talked to people who performed in 1969 and '70 and '72 and their management, and they are very aware of what's happening here this year and very interested in participating in the future," he says. "To the extent that this event is successful and advertisers and sponsors are on board for the future, we're going to be able to draw some incredibly talented and big name artists in the future."

For this year's acts, Partridge says the organizers curated a selection of national, regional, and local acts covering a range of styles, from the heavy, blues-rock of the Nick Moss Band to the more traditionalist leanings of Alabama Slim and Benny Turner, who also played the 1972 Blues and Jazz Festival.

"It's so significant to me not just that [Benny] is coming, but that he's so excited about playing here," Partridge says. "That connection to the old festivals and old Ann Arbor and what we accomplished was really important. That's something we want to carry through as we move up into 2019."

It's important to Partridge to honor those earlier festivals and the city's ties to the music while also building what he hopes will be a future for it, to the extent that he sought counsel from previous producers, like Peter Andrews and Sinclair. The latter actually made contact with Partridge when he heard what he was up to.

"I'm in my 50s, and I knew of John Sinclair through the John Lennon song," Partridge says. "He was larger than life. He was a legend to me. The fact that this guy who has been immortalized in song by a member of The Beatles wanted to talk to me was just, I couldn't even fathom that."

In the future, Partridge also hopes to do something ceremonial to honor Ann Arbor and the role it has played in blues music.

"I think it's time the city get its due and the people who participated in that and had the vision to do that at the time also get some recognition," he says. "I'd like the city to become proud of what it did and recognize what it did in terms of blues music and how it shaped what we listen to today."

Festival Lineup

1:00 pm - Blair Miller

1:30 pm - Tino G's Dumpster Machine

2:00 pm - Alabama Slim

3:00 pm - Hank Mowery & The Hawktones featuring Kate Moss

4:15 pm - The Norman Jackson Band

5:30 pm - Chris Canas Band

6:45 pm - Eliza Neals & The Narcotics

8:00 pm - Nick Moss Band

9:30 pm - Benny Turner & Real Blues featuring Brandon "Taz" Niederaurer

Related:

➥ Slow Burner: Alabama Slim at the Ann Arbor Blues Festival

➥ Put a Spell on You: Michael Erlewine on the 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival

Eric Gallippo is an Ypsilanti-based freelance writer and a regular contributor to Concentrate Ann Arbor.

The Ann Arbor Blues Festival is from 1-11 pm Saturday, August 19, at the Washtenaw Farm Council Fairgrounds, 5055 Ann Arbor-Saline Road, in Ann Arbor. Advance tickets are $35 ($17.50 for kids age 13-18, free for kids 12 and younger). For tickets and more info, visit a2bluesfestival.com.

Put a Spell on You: Michael Erlewine on the 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival

by christopherporter

During the early folk revival of the pre-Bob Dylan 1960s, music historian and author Michael Erlewine says fans were more interested in finding the most authentic form of the music than the next great songwriter. Conserving a dying art form was the priority at gatherings like the Newport Folk Festival.

So when music heads turned their attention to the electric blues, which was largely ignored on the folk circuit, they had the same impulse. But they soon learned it was misguided.

"We wanted to revive it -- to preserve it, protect it, and save it," Erlewine says. "But to our huge surprise, it wasn't dead. It didn't need reviving. It was just playing across town behind a racial curtain of some kind. To find what we thought was a dying music was very much alive, it was just another whole world for us."

In August 1969, a group of University of Michigan students led by organizers Cary Gordon and John Fishel, brought that world home to Ann Arbor with the first ever Ann Arbor Blues Festival.

As founders of the town's resident blues band, The Prime Movers -- which eventually featured drummer Iggy Pop --

and avid students of Chicago blues, Erlewine and his brother Daniel Erlewine were enlisted to help track down and care for the talent.

And there was so much talent: B.B. King, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Muddy Waters, Magic Sam, Big Mama Thornton, Son House. The list goes on. Nearly 20,000 people are estimated to have witnessed that first-of-its-kind gathering at the Fuller Flatlands near U-M's North Campus.

With another Ann Arbor Blues Festival reboot coming on Saturday, August 19, at the Washtenaw County Fairgrounds, it seemed like a good time to check in with Erlewine, who went on to found the All-Music Guide and edit several books on blues and jazz. His 2010 book with photographer Stanley Livingston, Blues in Black and White, is an excellent, loving tribute to the original blues festivals in pictures and prose.

Erlewine talked with us by phone from his home in Big Rapids about the heady days of those early fests, tripping out on Howlin' Wolf's massive voice, and drinking early into the morning with Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup and Big Mama Thornton.

Q: How did you first get involved with the original blues festival?

A: The group that started the Ann Arbor Blues Festival in '69, they hadn't been to Chicago, I don't believe. But we had been to Chicago and seen people like Little Walter and Big Walter and Howlin' Wolf and all these people live. So they turned to us, just because we were the only blues band around, and we knew not only the material but had met many of the artists.

Q: When you say us, you mean The Prime Movers?

A: Yeah, my band. My brother Daniel and I, primarily. He was the lead guitarist and I was the singer and harmonica player. We were totally bonkers on the blues and totally happy to be accessed. We ended up being in charge of taking care of the artists. We saw to it that they got food and also alcohol, so we were really popular.

This was the largest, and still is the largest, group of great blues musicians, especially electric, that ever was assembled. There's never been any group of blues artists larger than those (first) two festivals. The funny thing is, some of them started to arrive in Ann Arbor, for reasons I don't know, like a week before the festival. The university put them up mostly in the Michigan League or in West Quad.

We would go to the League or West Quad, and here were these great incredible people, like Big Mama Thornton or Big Boy Crudup, who is where Elvis' first song came from. I remember one time Dan and I went, and Big Boy Crudup was a huge guy, and he opened the door and there he was, and Daniel just opened his basket and showed him a bottle of Jack Daniels, and Big Boy Crudup just said, "Come on in, boys." We'd spend the whole night drinking whiskey and talking with him. We did the same thing with Big Mama Thornton and many other artists.

They had zero to do. They weren't used to coming. They were never amassed in that quantity ever. Maybe they saw each other at a club. They'd be crisscrossing at gigs, but never like 100 of them or more.

Q: Did you get a feeling there was a novelty to this for them? Were they like, "What is going on here?"

A: It wasn't, "What is going on here?" it was "Oh, is this wonderful." They were celebrating. We were exposing their music to a white audience for them mostly for the first time in quantity. They were amassing, celebrating one another and immensely enjoying being appreciated.

Q: It's hard today to imagine a first-of-its-kind blues festival. Electric blues is so ubiquitous now.

A: Not back then. Nobody thought that much of electric blues because it was not dying out. We concentrated on Chicago blues because they were our neighbors. They also had some of the greatest artists that ever lived. I mean, how much blues do you know?

Q: I know enough to know there are hundreds of names I don't know and never will. I like Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Magic Sam ...

A: If you like Magic Sam, going to see him in person was unbelieveable. His voice would literally raise the hair on the back of your neck. It was just so incredible.

The person who taught Robert Johnson his syncopated style was another blues guitarist named Lonnie Johnson, who was as old or older than Robert. We spent a whole afternoon in Canada interviewing him and hanging out with him.

We got smart early about trying to learn from these people. Not just their music, but what made their music so wonderful. There had to be something in them that made them great musicians. That was as interesting to me as the music itself.

That's how we wound up being in charge of those artists, and I ended up interviewing all of them. First with audio and then with video and audio, and then I went into the Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festivals and did the same thing. The university lost most of my stuff.

Q: The university lost most of your stuff?

A: Yep. There have been a number of historians who have gone down to Ann Arbor in recent years and tried to find it. They've searched and searched. I have written copies of some of it -- stuff that I transcribed. My Howlin' Wolf interview is pretty famous. John Sinclair says that's the finest Howlin' Wolf interview ever made, and I think so, too, because he's talking like an acid trip.

Q: How many hours of tape did you have?

A: I have no idea. Just lots and lots. Remember, I created the All-Music Guide and the All Game Guide. They just opened something in San Francisco a few weeks ago, the largest poster collection in the world, including 30,000 photos I took of posters. So, I'm very, very thorough. It was the same thing with those guys. I didn't care if it was a band member or it was a headliner, to me, they were the grandfather I never had. Their life wisdom was stuff I couldn't get on the street, and I couldn't get in Ann Arbor. When I talked to them, I asked them all kinds of stuff. I wish I did have it. I feel heartbroken.

Q: Did you find any common thread over the course of interviewing all these people?

A: The life wisdom they accrued from the suffering and stuff they had to go through just to survive. A lot of these guys carried guns and knives and, apparently, some of them used them. You weren't going to get that at Ann Arbor High School. We didn't know how it was to really live. I think that's what we learned along with their music, and we also played their music for years.

Q: Were there any noteworthy obstacles or opposition faced by the organizers or were people generally on board?

A: Originally the university organized a little group to have some kind of a music thing, and they wanted to kind of honor the blues, so they were thinking, believe or not, of bringing a U.K. artist, like John Mayall or somebody over. But John Fishel stood up to them and said, "Are you crazy? They're derivative. Why wouldn't you want to hear the sources themselves who are still living and the people who wrote all the songs these guys are covering?"

That's an obstacle he sorted out. Otherwise, we'd have heard just warmed over, U.K., Eric Clapton kind of stuff or Rolling Stones kind of stuff: what I call "reenactment blues." We instead had a festival with all the original artists.

Q: But as far as in the community or with the university, there was no trouble pulling this together as a group of young people staging a first-of-its kind event?

A: Not that I know of. You have to realize that the university, or even the rest of the crew, had no idea what was about to happen. How would they know? They might have heard Josh White or Art Tatum or something like that, but they had no idea what was coming down the pike.

Q: Were you surprised at all by how many people showed up?

A: It was a good crowd. I wasn't surprised. I didn't even think. It was just like, "These are the greatest guys in the world, of course you'd want to hear them." But it didn't occur to me how people would know enough to even want to come hear them. I didn't really think about that, but I probably should have.

Q: Why Ann Arbor? Why didn't this happen in Chicago, Detroit, Memphis, New York -- someplace like that?

A: The proper circumstances coalesced and came together and there it was. Why was Woodstock in Woodstock? I just think it was circumstantial. There was no second plan. There was nothing behind it trying to shine through. This was it. This just came together in a period in the world, and we all took advantage of it.

Q: What kind of lasting impact do those first fests have today?

A: First of all, most of the original artists have died. What you're hearing now, no matter how good they are, will never be the equivalent of the original, fresh, Chicago style. What you get now are, no offense, a reenactment of what it was. It's great that people love the blues. But who's going to sing like Muddy Waters? Who's going to sing like Magic Sam? Nobody.

Somewhere in my book, I think I describe what it was like to hear Howlin' Wolf in Chicago late at night one night. Nobody else there, maybe one person. It was just Wolf singing. For a while, I lost all sense of my body. I thought I was on an acid trip way out in the universe somewhere, because his voice -- you have to realize when these guys get in a groove, your and my sense of time is taken over by their sense of time, and they take us to places we've never been and will never get to and don't want to get to even.

Your sense of time would kind of fold into their sense of time, at least for the moment. That's what it was like.

There was no time in my life exactly like that one. Everything came together. Like a flower that blooms. We have a plant here called a night blooming cereus. It's a foot-long flower. It blooms for one night, then boom. It's gone in the morning. Those festivals were like that.

Related:

➥ Ann Arbor News coverage of the 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival.

➥ Memories of the 1969 fest by Jim Fishel, co-organizer of the original event.

➥ Cary Gordon, co-organizer of the original festival, shared his memories in the Ann Arbor News in 1992.

➥ Bob Franck's photos from the 1969 festival.

➥ The Michigan Daily's coverage of the 1969 fest.

➥ The Ann Arbor Chronicle's Alan Glenn recalled the 1969 festival in a 2009 column.

➥ Resurrected: James Partridge on the 2017 Ann Arbor Blues Festival.

➥ Slow Burner: Alabama Slim at the Ann Arbor Blues Festival.

Eric Gallippo is an Ypsilanti-based freelance writer and a regular contributor to Concentrate Ann Arbor.

The Ann Arbor Blues Festival is from 1-11 pm Saturday, August 19, at the Washtenaw Farm Council Fairgrounds, 5055 Ann Arbor-Saline Road, in Ann Arbor. Advance tickets are $35 ($17.50 for kids age 13-18, free for kids 12 and younger). For tickets and more info, visit a2bluesfestival.com.

From the Sludgy Banks of the Huron: Bubak at FuzzFest 4

by christopherporter

If you feel lured by some mysterious wailing over the next couple of weeks, be warned. Like the shadowy, mythic figure of its namesake, Ypsilanti-based stoner-metal duo Bubak are skilled in deception, masking sinister riffs and morbid tales within hook-filled earworms from which you may never escape.

"Bubak is from Czech folklore: pretty much their version of a Boogeyman," said drummer Justin O'Neill by email. This "scarecrow-looking creature, whose face is usually obscured by its hat," hides out by riverbanks and makes sounds like a baby crying, which lures unsuspecting victims to it. "Bubak then kills them, weaves their souls into garments, rides around in a cart pulled by black cats ... y'know, like a Bubak does."

Also featuring Jeff West on bass and vocals, the band is effectively the rhythm section of defunct psychedelic-metal band Zen Banditos, which split up when guitarist Andy Furda left town.

Bubak released its debut EP late last year online. CDs are now available, too, and the duo still plan to press it on vinyl. Like its fantastic comic-horror cover art by Tony Fero, the EP's four songs are as fun as they are menacing, heavy on fuzzed-out chromatic bass runs, swaggering shuffle beats, and West's awesome growl.

We traded emails with O'Neill and West in advance of their Thursday, June 1, show as part of FuzzFest 4 at the Blind Pig.

Q: How did the band get started? It's basically two-thirds of Zen Banditos, right? Was it as simple as Andy moving away and you two wanting to keep going, or did it take some time/trial and error to get to this point?

O'Neill: Yeah, pretty much. Andy Furda and we formed Zen Banditos after parting ways from the Mike Hard band. Andy has a really cool noisy, heavy psychedelic style on the guitar, and Jeff and I found our groove in the pocket and playing off of each other a lot, giving Andy the room to do his thing over top. After Andy made the move down to Arkansas, Jeff and I were already super comfortable jamming together, and it just seemed natural to keep going.

West: It was basically that simple. Since Justin and I meld together as a rhythm section so well, why stop true chemistry?

Q: The bass tone is so huge, and the drumming has so many things happening that it actually took me a couple of listens to realize this was just bass and drums and singing. How has losing the guitar affected the way you write?

O'Neill: It definitely has tightened us up. Jeff plays a riff, I’ll come up with a drum part. If we like it, we’ll expand on it. I’ve generally been in three-pieces in the past, so differing opinions and ideas were pretty easy to iron out. With a two-piece, it’s even easier. Jeff has hours and hours of music he’s written and recorded over the past two decades. I’ve heard him say, “I wrote that riff over 15 years ago,” several times. It’s really sweet to jam with a dude who knows his craft, has been doing it for so long, and there’s no bullshit involved. He’s the consummate musician.

I’ll let Jeff tell you why his bass sounds like that. I just hit things with sticks.

West: I got lucky achieving that tone. I just put the different Frankenstein rigs I have together. My bass runs through a guitar head into a bass cab, and the guitar tones are run through a bass head into a guitar cab, via a few pedals. I have really never used pedals before, and I am still getting used to it. There may be a POG (Polyphonic Octave Generator from Electro-Harmonix) or two involved in the mix.

Q: How does your history going back to playing in Mike Hard's band together play into what you do?

O'Neill: I was only playing in Mike’s band for a month or two. I’m pretty sure Jeff joined not too long before I did. Andy, who’d been playing with Mike for a couple years at that point, reached out to me to play drums for a couple of gigs. We played in Chicago and at Theater Bizarre. It was fun. Mike went a different route and reformed a different project with some guys he’d been playing with for years. Andy, Jeff, and I formed Zen Banditos.

West: Andy asked if I would want to jam [with Mike Hard] because their current bass player was exploring new ideas. Since Andy and I had jammed together before in ChristPuncher and Bonk, I said, "Yes," after not having played live with anyone in a decade. I am so glad I said yes because I would have never had the opportunity to jam with Justin.

Q: I hear what sounds like a pretty solid High on Fire influence in the vocals and intensity, but these songs are also super hooky. What are some recurring reference points for your sound? Any we might be surprised by?

O'Neill: For sure, you can hear a lot of the obvious influences in our music. High on Fire definitely, Sabbath, Melvins, older Clutch, etc. Honestly, I like a lot of random stuff. I'm a huge Ween fan, Mr. Bungle, The Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Jesus Lizard, Don Ellis, Santigold, Russian Circles, Bjork, A Tribe Called Quest, early thrash metal, early hardcore/D-beat. I could go on and on, but I'd say all the music I love sticks with me and influences me in one way or another.

West: For me, if it has a good melody and a strong groove, I dig it. I really dig a lot of different types of music, from jazz to funk to classical to rock, metal, blues, and try to incorporate that into what I play. It's all about how the riff makes me feel. Vocally, I wish I could sound like Paul McCartney in The Beatles' later years. ("Oh! Darling," "Helter Skelter") but that’s not gonna happen. So I do what I can.

Q: For the EP, it was interesting to me how a lot of the lyrics are very story-driven. Who writes the words and where do the stories come from? Are they exaggerations on real life or just pure fantasy?

O'Neill: Other than "The Fall" Jeff wrote all the lyrics. From what I can tell, they're all telling fairly fictional stories.

West: I will be the first to tell you I am not a lyricist. I can't write worth a shit. So my songs are pretty much just babbling about things I am thinking or see in movies. I get an idea and go with it. Yes, I do sing about weed a lot, because it's just so fun to sing about. It's not as evil as some would lead you to believe. Some of my best ideas are when I'm on that plane.

Q: From what I can tell, three of the four tunes are, in some way or another, about weed. I'm not positive on "Bio-Grey'd," but there seem to be clues. But "The Fall" is very clearly a call-to-arms of sorts for social justice and maybe Trump resistance. What was the inspiration for that song?

O'Neill: I wrote "The Fall." I just can't seem to write anything that isn't politically charged lately. There's a lot to be pissed about nowadays, at least for me and many others. It's a statement about how I'm feeling about different social issues -- systemic racism, cops beating and murdering people of color with impunity, Trump and his supporters’ dreams of a wall. That's the gist of that tune. If it inspires someone to speak up, write their congressmen or get out and protest, that’s awesome! It may be a little selfish, but it’s more of a way for me to get my thoughts and feelings out there.

West: "Hang Em' Higher" is loosely based on the Clint Eastwood movie Hang 'Em High. "Space Weed" is, obviously, about grass. "Bio-Grey'd" is purely sci-fi: creating a creature in a lab, and it gets loose and wreaks havoc on the world.

Q: What's next for the band? Any plans for a full-length?

O'Neill: A full length will happen. First, we wanna get the EP on vinyl, maybe a split with another band. Right now we're focusing on a handful of gigs, trying to raise funds for the vinyl, shirts, stickers, and other merch, and getting our music out there.

West: We are currently writing new material for [a full-length] and to extend the length of our set. And we just like jamming together. Why stop a fun thing?

Related:

➥ Read our interview with Fuzz Fest founder Chris Taylor and our articles on Fuzz Fest 4 bands Wizard Union, Junglefowl, and Scissor Now!.

Eric Gallippo is an Ypsilanti-based freelance writer and a regular contributor to Concentrate Ann Arbor.

Bubak plays Thursday, June 1, as part of FuzzFest 4 at the Blind Pig.

Exploring the vibrational universe of Avram Fefer and Michael Bisio

by christopherporter

If saxophonist Avram Fefer can play a compelling duet with a towering wall of sheet metal, chances are good he sounds great improvising with just about anyone. Which sets the bar pretty high for tonight's Kerrytown Concert House performance with longtime collaborator bassist Michael Bisio.

Fefer was recently in London for the latest session in his Resonant Sculpture Project -- which he described by email as "a series of immersive, site-specific performances exploring the relationship between improvisation, space, acoustics, permanence, and sculpture" -- during which the reedman plays at, around, and sometimes within the large-scale, minimalist creations of sculptor Richard Serra.

It's easy to imagine tonight's show going more like a conversation between old friends who happen to be experts in their fields; a two-person TED Talk on intersecting disciplines as told on reeds and strings.

Or as Bisio put it by email, "Both Avram and I tell a good musical story."

The two players, composers, and bandleaders have been telling that story together in some form since the 1990s, either in Bisio's Quartet or as a duo. Fefer's lyrical approach to sax and bass clarinet effortlessly folds in several styles to create an organic, singular sound that pairs perfectly with Bisio's limber double-bass lines and expressive bowing.

We talked with Fefer by email -- with Bisio chiming in, too -- about developing his rich, varied style; composing and tracking the duo's lone solo record in roughly 25 years of playing together; and how he got started jamming with inanimate objects.

Q: There's a really fluid blend of sounds in your playing -- from blues to Ethio-jazz to European "out" -- that all sounds very natural together. How did you come to appreciate and digest these diverse styles? Do you think in these terms when you're writing and improvising, or is it based more on feel?

Fefer: I’ve been told my playing shows a wide variety of influences. I guess I’m not surprised since I have had the pleasure of listening to and playing a lot of different music over the years. My earliest influences were Stanley Turrentine, Grover Washington, Stevie Wonder, Ohio Players, and all sorts of funky music. Later I became obsessed with a variety of sophisticated jazz, including straight ahead, free, and avant-garde. I lived in Paris and Barcelona for a few years and was introduced to an abundance of African Music -- North, West, East, and South -- but, honestly, I was not attracted to European improv at that time because as a young aspiring musician I was extremely focused on playing with my fellow Americans and learning from them. People like Bobby Few, Alan Silva, Archie Shepp, Kirk Lightsey, Steve Lacy, John Betsch, Rasul Siddik, etc.

I’m sure my music has been informed by my travels throughout the world, my embrace of different languages and cultures, and the huge influence of other arts, like literature, cinema, painting, dance, and sculpture. My main interest has always been producing music that is authentic, heartfelt, provocative, and organic. It needs to be approachable on different levels -- intellectually, spiritually, and physically. So long as these criteria are met, style is not really relevant.

Q: How did you and Michael first come to work together and what has kept it interesting for the two of you over the years?

Bisio: It was so long ago neither of us remembers the first time, but certainly in the early '90s we'd do West Coast dates. I was living in Seattle and Avram would come for visits. He was living in Paris and/or New York at the time.

Both Avram and I tell a good musical story. Therein lies the interest, not only for us but for everyone willing to journey with us. We also share a deep level of commitment to this music and strive to continually grow within its borderless parameters an entire vibrational universe.

Q: I could only find one duo recording of the two of you -- 2005's Painting Breath, Stoking Fire -- what were those sessions like to record, and why haven't there been any more since? Any plans to get back into the studio, just the two of you?

Bisio: I returned to New York in August 2005. If memory serves, this session is from earlier that year, maybe January. In addition to our duo, I was leading a quartet at the time with a front line of Avram and Stephen Gauci. Jay Rosen and I were the rhythm section. We were all part of the Cadence/CIMP (Records) stable, having recorded both as leaders and sidemen numerous times. Producer Bob Rusch wanted one Michael Bisio Quartet and one Fefer/Bisio Duo recording, both from the same couple of days. It was bitter cold that January in the North Country (of New York), and the fire in the Spirit Room (recording studio) was blazing on many levels. This situation had a profound impact on both recordings. The warmth of the studio was instantly vaporized by the stinging cold -- negative 14 degrees Fahrenheit. Waiting outside, your breath would simply hang in the air. Thus Painting Breath, Stoking Fire.

Fefer: We’ve only recorded one duo album, but we have five albums together as the Michael Bisio Quartet and have performed so many times as a trio and duo that I’m sure another small group document is not far off.

Q: There's a beautiful restraint to the playing on the album that's well demonstrated a little over halfway through "BC Reverie/Inner Child." It sounds like you're both playing free during this big climax, but it's still so controlled. How much thought goes into setting and keeping a tone like that, and how does locking in with another player at that same, measured pace work?

Fefer: I wrote the 60-minute suite that comprises the album specifically for Mike and I. I wanted to document a variety of ways we approach the duo format, including using a number of different textures and woodwind pairings with Mike’s bass. I think Mike would agree that most of the thought goes into the written material and choice of musicians. After that, we are expected to think, play, listen, and feel the music on a level that we’ve grown accustomed to in our travels and here in New York City.

Q: Where did the idea for the Resonant Sculpture Project come from, and what has the response been? Are there any sculptures you'd love to try playing with and haven't gotten to yet?

Fefer: I was performing with sculptures in the Hamptons, just outside of New York in 2012. I noticed that there were powerful acoustic effects produced by the sculptures as I was playing. This gave me the idea for my project, and I began searching for the best pieces to work with. I had always loved Richard Serra’s work and soon found that many of his sculptures were not only profoundly inspiring but also perfect for exploring sonic resonance with a live audience.

Musically, the challenge is to create a coherent improvisation that is expressive and compelling, while remaining open and responsive to the effects produced by the sculpture. I recently returned from London from what was probably the best event so far, and I have a list of 20 different Serra pieces around the world that are perfect for the project. My production team and I are in the midst of planning the next events now.

The audience reaction has been incredible at these events, and it’s especially rewarding to be able to share the excitement and surprise of live performance, sculpture, and sound exploration together.

Q: What else are you excited about working on currently or do you have coming up down the road?

Fefer: Mike and I have a trio with Michael Wimberly that will play more in the future, and I am supposed to go to Paris to play with my old friend Bobby Few, with whom I’ve recorded a number of albums. I will continue to play regularly with Adam Rudolph’s Go:Organic Orchestra and Greg Tate’s Burnt Sugar, two very different, but equally amazing ensembles.

I am especially excited about two recent projects of my own that are in the middle of recording our first albums. One is a four-piece abstract, electric groove ensemble called Rivers on Mars that features laptop, electric guitar, drums, and myself, and the other is a three-piece African Chamber Ensemble, featuring percussionist Tim Keiper on Malian ngoni (string instrument). These groups are on opposite ends of the sound spectrum, but I love them both and they are equally challenging to me as a player.

I also continue to play with my six-piece Afro-funk project Big Picture Holiday, which features Kenny Wessel and Alexis Marcelo, among others. Our debut album (Shimmer and Melt) came out last year on Ropeadope Records and, thankfully, people seem to love it!

Eric Gallippo is an Ypsilanti-based freelance writer and a regular contributor to Concentrate Ann Arbor.

Avram Fefer/Michael Bisio Duo play on Monday, April 24 at Kerrytown Concert House, 415 N. 4th Ave., Ann Arbor, at 8 pm. Tickets are $5-$30.

Need a light? Wizard Union Collective carries a heavy torch

by christopherporter