Clarinet Sour Notes Over, Triumphant Inventors Say

Parent Issue

Day

27

Month

October

Year

1950

Copyright

Copyright Protected

- Read more about Clarinet Sour Notes Over, Triumphant Inventors Say

- Log in or register to post comments

Woodwind 'Stradivarius' Carries On Trade Here

Parent Issue

Day

22

Month

May

Year

1953

Copyright

Copyright Protected

- Read more about Woodwind 'Stradivarius' Carries On Trade Here

- Log in or register to post comments

Inventor Honored: Elijah McCoy's Name Signifies High Quality

Parent Issue

Day

28

Month

June

Year

1994

Copyright

Copyright Protected

Legacies Project Oral History: Larry Millben

Lt. Col. Larry Millben was born in 1936 in Detroit. His parents immigrated from Chatham and Windsor, Canada. Fascinated by airplanes from an early age, he was one of only a few Black students to attend Aero Mechanics High School (now Davis Aerospace Technical High School) in Detroit in the early 1950s. Millben went on to become an aircraft mechanic, a military avionics officer, and base commander of Selfridge Air National Guard Base. Prior to his military career, he also worked in research and development in the private sector. He married his wife Jeannie in 1959, and they have three children.

Larry Millben was interviewed in partnership with the Museum of African American History of Detroit and Y Arts Detroit

Local Men Develop, Sell Colorant Dispenser Unit

Parent Issue

Day

24

Month

October

Year

1959

Copyright

Copyright Protected

- Read more about Local Men Develop, Sell Colorant Dispenser Unit

- Log in or register to post comments

Spaghetti Fork Patent Received By Fenerli

Parent Issue

Day

30

Month

January

Year

1970

Copyright

Copyright Protected

- Read more about Spaghetti Fork Patent Received By Fenerli

- Log in or register to post comments

Gelman Develops Method To Treat Polluted Water

Parent Issue

Day

15

Month

June

Year

1987

Copyright

Copyright Protected

- Read more about Gelman Develops Method To Treat Polluted Water

- Log in or register to post comments

Local Inventors Seek Patent For Their 'Energy Device'

Parent Issue

Day

17

Month

April

Year

1975

Copyright

Copyright Protected

- Read more about Local Inventors Seek Patent For Their 'Energy Device'

- Log in or register to post comments

Omnitext, a local manufacturer of video display terminals

Parent Issue

Day

24

Month

January

Year

1975

Copyright

Copyright Protected

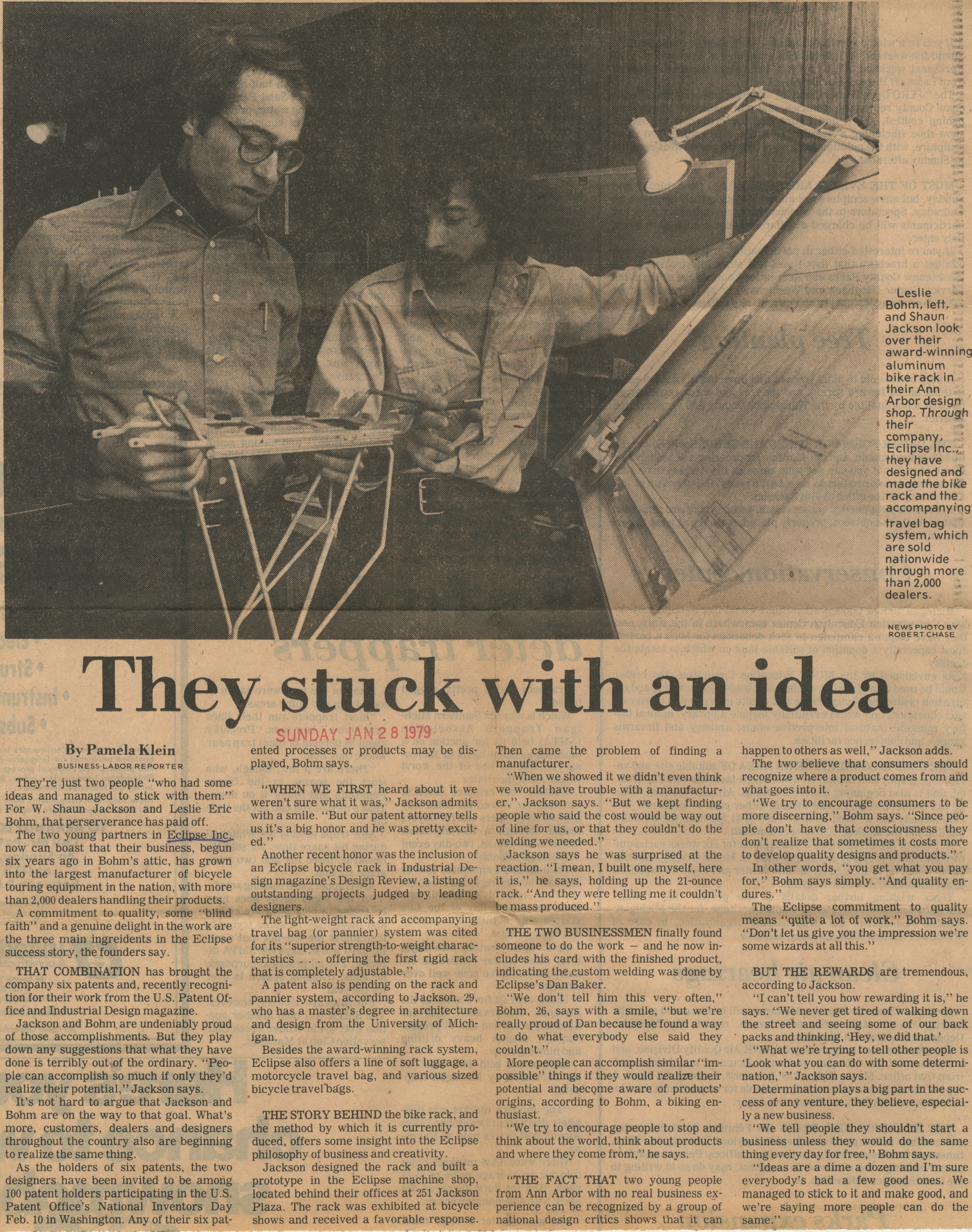

They Stuck With An Idea

Parent Issue

Day

28

Month

January

Year

1979

Copyright

Copyright Protected

- Read more about They Stuck With An Idea

- Log in or register to post comments