A Full Dance Card: Ann Arbor's Chequamegon Band & Orchestra

It was a crisp Tuesday evening, the last week of April 1884. Hundreds of people gathered in downtown Ann Arbor. Outside a new brick building, near the corner of Ashley & Huron Streets, they waited for the city's first roller rink to open its doors. By the end of the night, roughly 700 people had enjoyed roller skating to the marvelous music performed by the Chequamegons. During intermissions, starstruck women approached the handsomely suited musicians, hoping to find a skating partner. The Chequamegons were in constant demand. Their performances always guaranteed a crowd. The Rink, as it was known, would eventually disappear into Ann Arbor's past. The Chequamegons may not sound familiar to you either, but this talented group of students laid the groundwork for University of Michigan bands and orchestras, and were shining stars in Ann Arbor's music history.

1880 - 1883: MUSICIANS WANTED

In the early, early days of the University of Michigan, music was not an educational offering. If a musical group was to form on campus, it was up to student musicians or vocalists to find each other, provide their own resources, and hatch a plan that everyone could agree on. Professional orchestras, like The City Band of Detroit, were hired from outside the university for major events like commencements. This is not to say that student musical groups didn't exist, but they came and went as frequently as the student population enrolled and graduated.

In 1880, Fred Hamilton Weir was a University of Michigan student from Indiana. When he wasn't studying for his medical degree, he was trying to create a musical group on campus. He managed to arrange a small--yet talented and enthusiastic--orchestra of medical and dentistry students. Their first few years together were haphazard and inconsistent. Their lucky break came when Sarah Caswell Angell, wife of the University's president, invited them to perform at a commencement reception. The group called themselves the U of M Orchestra, despite having no formal support from the University. In June of 1883, the stars aligned for these young performers when they were offered a three month paid position at the Hotel Chequamegon in Ashland, Wisconsin. Five musicians from the group - Fred Hamilton Weir, Herman Frank, Stanley Holden, Will Park, and George A. Isbell - accepted the opportunity. They invested in uniforms, which were manufactured by Ann Arbor clothier A. L. Noble, and travelled to Lake Superior for a summer residency.

The name Chequamegon (prounounced “shi-wa-me-gone”) is of Ojibwe origin. It is derived from chagaouamigoung, a French transliteration of the Ojibwe Zhaagawaamikong or jagawamikiong, meaning a "a sand bar place" or "place of shallow water". In this case, it refers to Wisconsin's Chequamegon Bay on Lake Superior. Performing as summer musicians overlooking the bay, the U of M Orchestra began calling themselves the Chequamegon Band And Orchestra. When they returned to Ann Arbor, they brought their new name with them.

1884: ANN ARBOR'S CELEBRATED BAND

Looking back on the history of this musical group, 1884 is when the Chequamegon Band And Orchestra was fully formed. The number of musicians in the band grew. Homer Drake, a dental student, joined the band and assumed leadership with Fred Weir. During the years 1884-87, the Chequamegon group retained their original members although a percussionist and a clarinet player were eventually added. Soon it seemed that every notable city event (like the opening of the skating rink mentioned earlier) was accompanied by a Chequamegon performance, and the band was tightly woven into the fabric of Ann Arbor. Usually around nine or ten musicians, they were able to "double" on both string and wind instruments. This versatility meant they could function as a brass band or string orchestra, whatever was appropriate for the situation.

One important factor in their popularity was that the University of Michigan did not have dormitories in the 1800s. Ann Arbor's population in the 1880s was roughly 8,500 people, and U of M students were living in boarding houses and rented rooms around the small city. The line between "town and gown" was nothing like it is today. The Chequamegons, as they were locally known, became popular not only with students, but with Ann Arbor residents as well. Many fans referred to them as "Ann Arbor's Celebrated Band", disregarding their student status altogether.

WHEN DID THEY HAVE TIME TO STUDY?

Led by Homer Drake, and later by his brother, Rollin E. Drake, the ensemble often performed at Ann Arbor’s St. James Hotel and played many, many evenings at The Rink. If a parade happened in Ann Arbor, the Chequamegons would be there. Dedication of a new building? Major city event? The Chequamegons would be there. In June of 1884, 10 members of the band headed back to Ashland, Wisconsin for another summer residency at the Chequamegon Hotel. This happened after the group played at numerous commencement ceremonies around the greater Washtenaw County area. Knowing how popular the band was, the town of Ashland went as far as to advertise tourism within the University of Michigan's 1884 commencement program - "Where the University of Michigan Band Plays!".

In 1885, Ann Arbor's Masonic Temple was dedicated and, of course, the Chequamegon orchestra played the event. They could also be seen performing in the 1884-1885 University Musical Society concert season. 1885 was the year that the University of Michigan first won a national collegiate championship. When fellow medical student Fred Bonine helped lead the track team to victory, the Chequamegon Band played at his welcome home celebration. Band members were making enough money from their frequent performances to pay their college expenses. In the summer of 1885, the group took a break from Wisconsin and spent two months in Marquette, Michigan. They split their time between performing at a popular roller skating rink and a residency at the Clifton House Hotel.

In 1886, The Chequamegon Band and Orchestra incorporated, becoming an official business entity. The demand for their performances held steady, and they spent the summer back in Ashland at the Hotel Chequamegon. 1887 saw a change in the band's lineup as several original members graduated, but the group continued to be successful. It became standard practice for area schools (Saline High School, in particular) to fundraise annually in hopes of hiring the Chequamegons to play their commencement ceremonies. One of the groups most notable gigs came in the summer of 1889 when they spent three months playing at Plank's hotel on Mackinac Island--better known to us today as The Grand Hotel, Michigan's beloved home away from home. They even performed on the boat ride north.

In 1893, the Ann Arbor Argus published "A Successful Organization" about the group's unwavering presence around town. "The dull times does not seem to affect the Chequamegons. Last Thursday evening they furnished music for the Kennedy wedding; last Friday, for Foley Guild dance at Nichols'; Tuesday night, for the Hallowe'en party, at Nichol's, tonight they play for the Wolverine Cyclers; tomorrow evening for the freshman spread, at Granger's, and Saturday, for Hobart Hall social. They have also secured the contract for furnishing the music for the El Astro Club series of five parties, and the Thanksgiving party, at Ypsilanti." Maintaining a schedule like this, along with an education in medicine or dentistry, must have been a challenge.

CHEQUAMEGONS IN THE 20TH CENTURY

On June 20, 1900, the Ann Arbor Courier-Register reported "The Chequamegon orchestra is probably the busiest musical organization in the state these days. They have so many engagements that it is necessary to secure a few outside men for assistance. Dundee, Manchester and Pinckney are among the out of town places that will hear Ann Arbor musicians this week." Despite the great demand, popular music and dancing styles were changing, and band member numbers began to dwindle. The University of Michigan's School of Music had emerged, numerous local music groups had formed, and musically-inclined students had a much wider variety of opportunities to choose from around Ann Arbor. Student turnover at the university continued to be a factor as well. 1902 saw one of the final summer residencies of the Chequamegons, on Stag Island in the St. Clair River. In 1903, the Chequamegon Orchestra played at the wedding of their trombone soloist, Louis Otto. Otto was the leader of his own band, and was one of the most popular musicians in Ann Arbor. 1905 was the last instance of the Chequamegon Orchestra being listed in the Ann Arbor City Directory, and soon the pioneering group became part of the city's history.

Years later, in 1954, The Michigan Daily interviewed retired dentist Dr. Rollin E. Drake ('88D) about his time in the Chequamegon Orchestra and Band. "We had to buy our own music, hire halls and make contracts," Dr. Drake said. Speaking about a long-running position at Ann Arbor's Whitney Theatre, "The rottener the show, the more the music was needed. We would play in the pit, while the greats like Edwin Booth and Madame Modjeska were on stage. For those engagements each man was paid $1.37 per engagement, including rehearsal time." Drake, like many of his fellow bandmates, went on to a career in medicine. Others became bankers, judges, and businessmen. Some, like Edward N. Bilbie and George A. Isbell, continued on to professional careers in music.

MAY I PENCIL YOU IN?

This dance card, from an 1888 Chequamegon Orchestra formal, was an important piece of social etiquette. Ladies would wear these on their wrists, to keep track of the music and who their dance partner would be for each song.

Thanks to the Library of Congress's collection of audio recordings, you can hear a few songs that were played at this event. To immerse yourself in the Chequamegon music scene of the late 1800s, give the following playlist a listen:

- WALTZ, Dreams of Childhood, Emil Waldteufel

- WALTZ, Erminie: Selection, Edward Jakobowski

- SCHOTTISCHE, I'm Happiest When I Dance, J. Lemoire

- WALTZ, Gypsy Baron, Johann Strauss

Dance Card - Interior, The Chequamegon Dance, November 23, 1888. Courtesy Of The University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library.

Ann Arbor Yesterdays

- Read more about Ann Arbor Yesterdays

- Log in or register to post comments

D. S. McIntyre, Theater Owner, Passes At 76

- Read more about D. S. McIntyre, Theater Owner, Passes At 76

- Log in or register to post comments

Stage, Screen

- Read more about Stage, Screen

- Log in or register to post comments

Stage, Screen

- Read more about Stage, Screen

- Log in or register to post comments

Stage, Screen

- Read more about Stage, Screen

- Log in or register to post comments

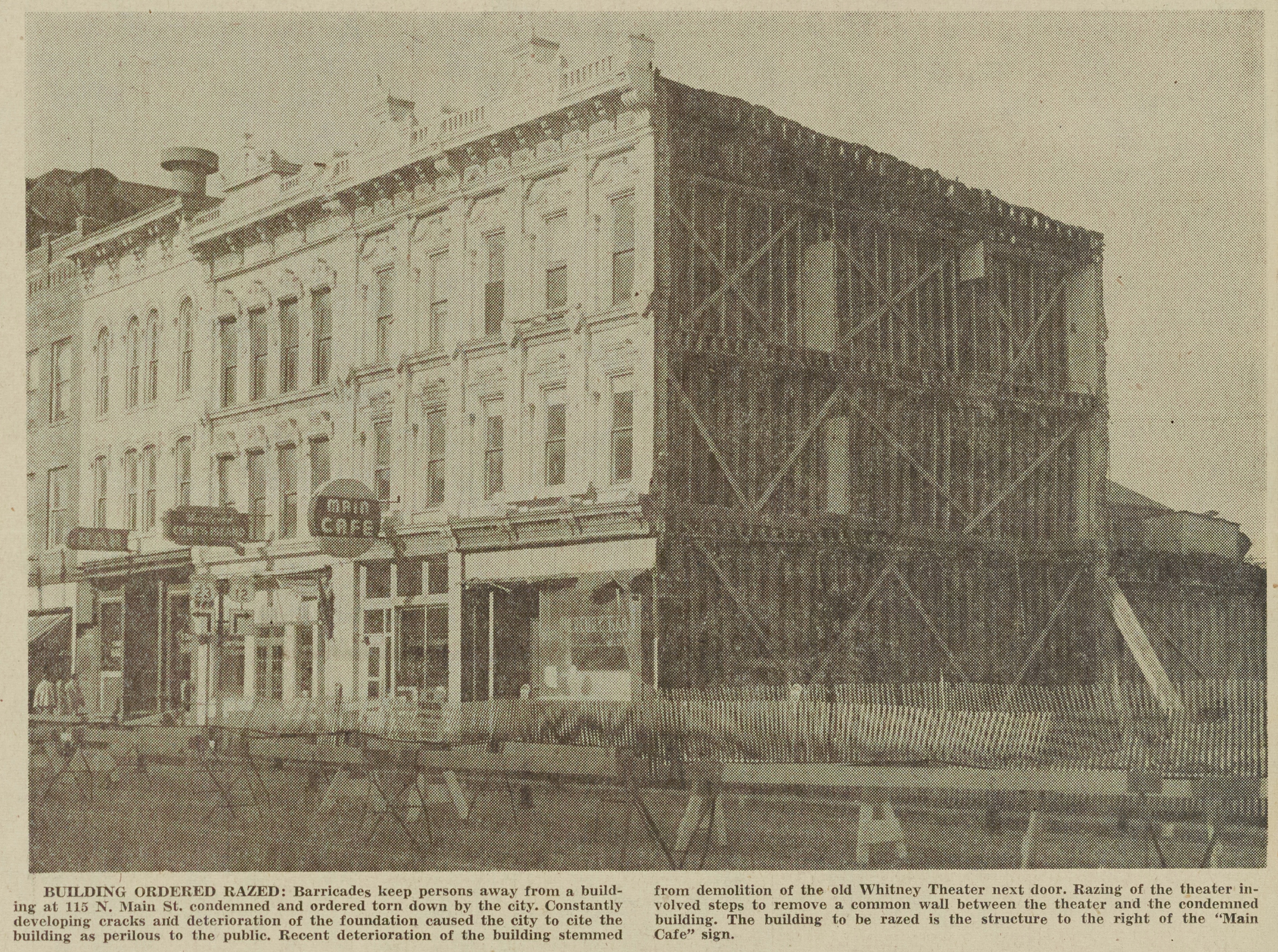

Building Ordered Razed

- Read more about Building Ordered Razed

- Log in or register to post comments

Main St. Building Demolition Starts

- Read more about Main St. Building Demolition Starts

- Log in or register to post comments