Manchester Mill

The landmark that shaped the village

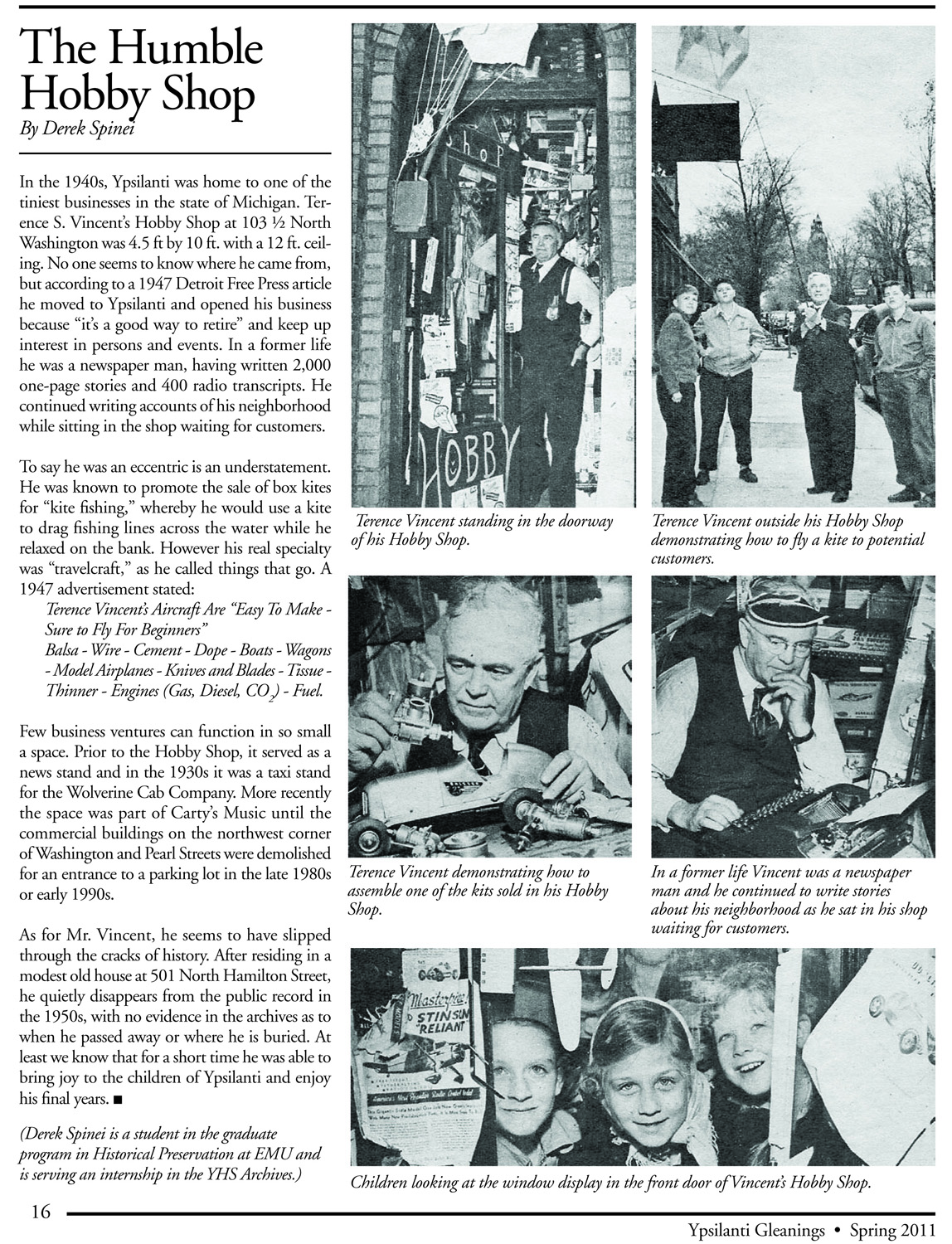

Perched on the edge of the bridge in the center of Manchester, the Manchester Mill visually defines the town. Historically, the mill is the reason for the village's existence.

In 1826, John Gilbert bought the land that would later become Manchester. He contracted with Emanuel Case and Harry Gilbert to build a mill on the River Raisin in 1832. Since then, there has always been a mill on that site—although the building has burned down twice and the dam has been rebuilt twice.

According to Chapman's 1881 History of Washtenaw County, Case built a gristmill and a sawmill. Those mills, plus one on the east side of town (now the site of a Johnson Controls factory), furnished the power that made Manchester a leading nineteenth-century industrial town, served by two railroad lines. Case also built the first hotel in Manchester and was the village's first justice of the peace, office in his hotel.

Out of the three mills, the grist the only one that has survived—and it has had to be rebuilt repeated mill burned for the first time in 1853.

Though an exact cause was never determined, fires were common in mills because of the high flammability of grain dust. With wooden buildings and low-tech volunteer fire departments, they would spread quickly. The 1853 fire swept half of the downtown, destroying fourteen businesses and one dwelling before being brought under control.

In 1875 and again in 1908. the River Raisin flooded and washed out the dam. After the second flood, a temporary dam washed out again just two months later. It was replaced with sixty-foot-wide poured-cement structure, which has lasted to this day. Don Limpert, present owner of the Manchester Mill, believes the dam one of the oldest poured-cement structures in the state.

The mill burned for the second time in

By the time the night watchman

red the fire and sounded the alarm,

were shooting through the sides of

ding. The mill was rebuilt again,

it opened for business in January of 1926, it no longer ground flour, just feed for livestock.

Although Henry Ford bought most of the mills in the area, including the one on the east side of town and mills in Saline and Dexter, he decided the Manchester Mill, at a price of $6,000, cost too much. The high price probably reflected the fact that the mill was still in use, unlike the abandoned mills he usually purchased.

E. G. Mann and his two sons, Willard and Earl, bought the mill in 1940. E. G. had been in the mill business since 1927, when he bought a feed mill in Bridgewater, which is still run by his descendants. In 1976, Willard's son, Ron Mann, who had been working at the Manchester Mill, took over. Ron remembers that in the 1960s, the mill was open from 7:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. and that the workers were grinding all day. But by the time he became the owner, grinding was only about five percent of the business, and more of a service than a moneymaker. The surrounding farmland was being steadily sold off until there were hardly any livestock farmers left. (Today there is only one full-time livestock farmer in Manchester Township.)

In 1981, Mann decided to end the milling part of his business; at the time, it was the oldest operating mill in continuous use on me same site in the entire state. By then, he had expanded into lawn and garden supplies and premixed animal food. He moved this part of the business to the west side of town, where it is still running, under a new owner.

After Don Limpert bought the old building from Mann, he removed the mill equipment, some of which had to be taken out through the roof by a crane. Limpert, who has restored numerous other buildings in Manchester, divided the mill into smaller spaces, starting with an apartment at the top that he calls "Manchester's high-rise." (Bill Farmer, a former member of the Raisin Pickers string band, lives there.) The remainder of the space is rented by stores and businesses. One of the turbines is still in place and could be used to generate electricity if ever needed.

A feeling of the old use still pervades the mill. One of the turbines is used for a coffee table in the Red Mill Cafe, and an original corn-shucking bin empties into the office of the Manchester Chronicle, where editor Kathy Kueffner looks out at the River Raisin while she writes her copy.

—Grace Shackman

Photo Caption: Through fire and flood, Manchester's mill ground grain from 1832 to 1981.

Turning the clock ahead in Dexter

From car showroom to coffee shop

Before car salesrooms and gas stations were relegated to the outskirts of town, Ralph Kingsbury's Ford dealership stood on the corner of Main and Broad streets in Dexter. Today the building is the Clock Works Coffee house.

"It's as different as you can get in the same space," says Elizabeth Kingsbury Davenport, Kingsbury's daughter. The Clock Works, although located in the former dealership's post-Civil War Commercial Italianate building, manages to look very modem and airy with exposed brick walls, scenic watercolors, and generously spaced tables and chairs.

In Davenport's time, when her father's business included the main storefront, a garage on the east, and gas pumps on the west, this same site was anything but open: a single Ford floor model took up most of the showroom, surrounded by vats of car parts, barrels of freebies for the gas station, and cane-bottom chairs for people to sit on while they waited for their cars to be repaired.

Harvey Blanchard opened Dexter's first Ford dealership in 1911. Ten years later he started a bus line between Ann Arbor and Dexter using Fords. In 1926, in the last years of the Model T, Blanchard gave up the car business and Kingsbury took over.

"He always loved cars," recalls Davenport of her father. "He drove a Studebaker, but the Dexter Ford dealership was open and his mother bought it for him."

Kingsbury had graduated in 1912 from the U-M's railroad accounting program, the precursor of today's business school. He had been working for the Pere Marquette Railroad in Detroit when the opportunity arose. He moved to Dexter with his wife, Marian, who became the local piano teacher; their three young children, Elizabeth, Doris, and Stewart; his mother, Loretta Kingsbury; and his mother-in-law, Jennie David. They were later joined by his brother-in-law, William David—"Uncle Will," as Davenport knew him.

The new ownership was celebrated with a grand opening. The building was decorated with red and white flags furnished by the Ford Motor Company, and salami, liverwurst, cheese and crackers, and pop were served inside. According to Davenport, the fanfare was probably a bit "too much" for local residents. "They were used to a quieter approach," she explains. "It was a farming community. There were some prosperous farmers, but it was not a rich community. People lived simply. They played cards on Saturday night; they went to weekly dances or church suppers."

If the opening sparked any resistance among members of the community, it didn't affect the business, which grew big enough to employ three mechanics, two salesmen, and a bookkeeper. Davenport remembers her dad sitting at his Mission-style desk in the back of the store wearing a green visor and cooling himself with a palm-leaf fan. In front of him stood the dark green metal counter. With an old-fashioned cash register and a Philco beehive radio. Uncle Will, a short man who always wore a hat—either a fedora or, in summer, a straw boater—managed the two gas pumps (regular and ethyl), although "whoever was around did the gas. They didn't exactly line up for service," Davenport says. To keep customers coming, premiums were given for buying certain amounts of gas. Davenport remembers Depression Glass dessert plates, cups and saucers, creamers, sugars bowls, and salad plates, later replaced by lacy pressed glass that was a yellow-amber color, a light green, or pink.

The store itself was decorated in "Ford Motor olive drab," recalls Davenport. The company had a standard look for its showrooms and sent out posters of cars, large cardboard cutouts of cars, ad materials, and flyers, things that all Ford dealers were expected to use. The repair area (now a video store) was connected to the salesroom by a side door; it had roll-up garage doors on the street, an oil-change pit (hoists were rare in those days), and a back door large enough for cars to exit to the alley.

In the early days of the dealership, Kingsbury sold one car at a time—after a customer bought the floor model, he would order another. Occasionally a Fordson tractor or an additional car or two would be on display outside near the gas pumps.

Later Ford switched to a quota system, sending a car hauler with Kingsbury's assigned delivery. New models were celebrated at the dealership with blue and white triangular banners, while yellow banners were used for special sales. Davenport still remembers the day in 1927 when the Model A was introduced: "I went to the candy store and told them it went sixty miles an hour. They didn't believe me."

Once a month the Ford road man came and inspected the books, an event that Davenport recalls as "always stressful." Henry Ford's visits were even worse. He and his henchman, Harry Bennett, would park in front and "sit and watch," she remembers. "It was like God watching. We were paralyzed with fear and not allowed anywhere near them."

When the Great Depression hit, it was harder to sell cars. "Dad sold a lot of cars to U-M faculty and to his frat brothers or their friends. The repair work was for Dexter folks," recalls Davenport. Area farmers needed to keep their old trucks and tractors running and would sometimes bring them into the dealership "literally held together with baling wire. Dad had a soft heart and knew you couldn't farm without gas. Some people paid their bills with in-kind goods instead of money, a practice frowned on by Mr. Ford, but we ate very well," she says.

During the depression the car dealership was also the repository for surplus food, which was lined up against the west wall. People came in and signed for the food they took. "I was embarrassed that people had to come in and pick up food. I'd always make myself scarce when I could," recalls Davenport.

Kingsbury moved the dealership twice, each time to bigger quarters—first to the top of Monument Park in the building now home to Cottage Inn pizza, and then to the top of the hill, now an AAA office. In 1941 he sold the business to Al Gross, who had been a salesman with him from the beginning. Kingsbury took a job as bookkeeper at the Buhr Tool Company in Ann Arbor, where he worked until he retired. He died in 1976.

After Kingsbury moved out of the Blanchard building, it stood empty until 1944, when Art Lovell moved his appliance store into it from across the street. Lovell, an excellent mechanic, kept the garage as a car repair place and continued to run the gas station, although he changed it to a Dixie Gas station, supplied by the Staebler Oil Company of Ann Arbor. He used the storefront to sell Frigidaire appliances. As engines improved and cars needed fewer overhauls, he segued into doing more appliance repair.

Kate and Mike Bostic opened the Clock Works Coffee Shop in the building in 1997. They survived the first two years despite heavy construction going on around them. "Fortunately we're serving an addicted population," laughs Kate. In addition to coffee the Bostics serve morning snacks and light lunches. They are obviously filling a community need; people come in on the way to work, parents stop in after dropping their children off at school, and local merchants come in for lunch. In warm weather, people can drink their coffee at tables on the side of the building where the gas pumps once stood.

In one respect the present operation is not as divergent from the car dealership as it seems. Davenport recalls that when her father ran the place people came in throughout the day, some waiting for their cars to be fixed, others stopping in if they were buying gas or just passing by. Although the dealership didn't serve coffee (as many do now), "there were newspapers to read," says Davenport. Or, she adds, people would simply drop by, coming in to "sit and talk"—just as they do at the Clock Works today.

—Grace Shackman

Gunther Gardens

A motionless windmill marked the gardens of a renowned landscape architect

For many years, a huge deserted windmill north of Saline puzzled those who passed by it on Ann Arbor-Saline Road. Neighborhood children said it was haunted.

The windmill never ground grain. It was actually built as a tearoom for the Gunther Gardens, a formal garden and nursery that operated from 1927 to 1939. Developed by Edmund Gunther, a brilliant but eccentric landscape architect, and his hardworking wife, Elsie, the gardens covered 160 acres.

The "windmill" was an inspired piece of recycling: it was built around the remains of an old silo. The tearoom's sixty-five-seat dining room, which occupied an addition around the base, was furnished with Arts-and-Crafts-style handmade furniture and wrought iron lantern-style lamps. The silo itself contained the kitchen, bathrooms, and a stairway that led to a balcony. From the balcony, visitors could see the gardens spread out below them and the vanes of the windmill rising above them.

"It didn't rotate; it was just for looks," explains the Gunthers' son, also named Edmund.

Why did Gunther build it?

"When you live in Europe, you have different ideas," says Gunther's daughter, Viola Hall.

The tearoom was not open to the public but was used for special events. Groups such as garden clubs or university organizations would book special events at the tearoom. They'd come for a catered meal, a talk by Gunther, and a tour of the gardens.

Because of the windmill, many assumed that Gunther was from the Netherlands, but actually he and Elsie were born in Germany. He studied landscaping in Zurich before immigrating to the United States and attending theology school in Rochester, New York, to become a Congregational minister.

"During World War I, he couldn't preach," says Hall. "They thought he was a German spy. So he moved lo East Lansing and got a degree in the [MSU] landscape program." Gunther worked at a botanical station in Florida and then moved to Ann Arbor to work as a landscape architect.

In 1926 the Gunthers bought a dilapidated farm outside Saline and developed their gardens. They filled in a swamp with loads of dirt. Elsie Gunther, who had learned gardening from her father, supervised the crews and selected the plants. Edmund was the dreamer. "His head was always up in the clouds," recalled Elsie in a 1976 interview.

Edmund Gunther's specialty was wild gardens, so his showpiece featured plants native to the area. Artesian wells on the property fed a kidney-shaped pool with a waterfall in front of the teahouse, and an artificial lake behind Gunther's office. He created rock gardens and sunken gardens, to give potential buyers ideas of what could be done with the plants he specialized in. He increased the variety in his designs by changing the temperatures in his greenhouses, forcing plants to bloom early or holding them back. He went to Indiana to collect dogwoods, to the Carolinas for rhododendrons, and to northern Michigan for cedars.

Gunther's unusual designs brought him awards and wealthy customers. He landscaped factory sites, Hillsdale College, a park in Adrian, and residences in most of southeast Michigan's affluent suburbs. In 1927, he won first prize at the North American Garden Show with a wild garden exhibit. He won again the next year, this time with an octagonal garden. He created a ten-acre flowering meadow for Detroit industrialist William Knudson, and a lavish garden to set off a display of new Chryslers. He also worked for Henry Ford—once designing a rose garden for Ford's wife, Clara—and Ford visited periodically to talk about soybean farming.

Gunther Gardens was a critical success, but not a financial one. During the Great Depression, landscape gardening was a luxury few could afford. The Gunthers tried every way they could to keep the business afloat, including renting out some of the land to farmers. The younger Edmund Gunther recalls that at the end, his dad was working with a religious group in Cleveland to re-create the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, trying to develop a synthetic rubber out of milkweed (in anticipation of World War II), and building dormitories behind his house in hopes of offering classes on landscaping.

But the Gunthers couldn't make the payments on their land contract, and their endeavor ended inelegantly. The sheriff's deputy evicted them, throwing all their possessions out on the road.

The Gunthers were devastated. Their marriage ended, and they both went through hard times for a while. Edmund remarried and returned to the ministry at a small church in Gibraltar, south of Detroit. Elsie moved back to Ann Arbor and ran several boardinghouses, with the financial help of Clara Ford. She showed her gratitude by baking Clara coffee cakes.

After the Gunthers left, the gardens became overgrown, but the windmill remained standing until 1965, when it fell over in a storm. About five years ago, Ann Arbor's Guenther Building Company—no relation to the Gunther family—bought the land and developed it into a subdivision. It was also named Gunther Gardens in honor of the family. In a touch that Edmund Gunther himself would surely have appreciated, the company built a faux-historic covered bridge at the entrance.

—Grace Shackman

The Aura Inn

The heart of Fredonia

"I'm surprised at how many people say, 'I met my husband at a dance at your dad's place,' or 'I met my wife at a dance there,'" says Billie Sodt Mann, whose father owned the Pleasant Lake House from 1925 to 1943. A bar and restaurant now known as the Aura Inn, the Pleasant Lake House was the center of Fredonia, a hamlet that in the nineteenth century was large enough to have its own post office. Many people in the area have happy memories of swimming, fishing, picnicking, and dancing there.

Situated on Pleasant Lake, in the middle of Freedom Township, the inn began in a two-story house that was built about 1880 by German immigrant Jacob Lutz. Since Fredonia was a pleasant stopping point between Ann Arbor and Jackson, and the lake an enjoyable place to relax, Lutz turned the front part of his house into a saloon and grocery store and rented upstairs rooms to travelers.

The next owner, David Schneider, added a dance hall upstairs. In the early 1920s, when guests began arriving by automobile, he dismantled the barn and used the wood to build a bigger dance hall, with a high, beamed ceiling, down by the lake. The hall boasted a hardwood floor, a loft where bands played, tall windows to let in light, and two wood stoves in opposite corners for heat.

Manny Sodt bought the inn in 1925 and moved the dance hall next to the house (it took a whole summer, with relatives and volunteers helping) and added electricity and central heating. The spot by the lake became a campground and boat rental; abandoned waiting rooms for the interurban trains, which had recently been discontinued, were moved to the site and made into vacation cabins. A former policeman (he was Ann Arbor's first motorcycle cop), Sodt enforced rules of good conduct. "No one did anything bad. You'd quiet down or you knew where you were going: to jail," recalls Mann.

On weekends the grounds were used for all-day picnics, weddings, or family reunions, with dances in the evenings. "Friday was old-timers' night. They did square dances and waltzes," remembers Mann. "On Saturday it was more modern. The bands didn't have a name; it was 'this guy and that guy.'" The Friday night crowd tended to live nearby; Saturday night dances attracted younger people from farther away. Mann sold tickets while her older sister, Ginnie, helped their mother sell hot dogs and coffee during intermission.

In failing health from a weak heart, her father sold his place in 1943. He died the day the papers were signed. The new owner, Ray Hoener, installed an antique bar—which is still there—in the dance hall. Rich Diamond, the present owner, took over from Vicky and John Weber, who owned the place from 1965 to 1978.

County commissioner Mike DuRussel worked for the last two owners. "I learned my diplomacy cracking heads and pouring drinks," he jokes. The Webers were deeply rooted in the community, and they attracted a crowd of locals with lunch specials and weekly euchre and pool tournaments. They also sponsored a Pleasant Lake Inn baseball team—most of the players drove beer trucks for a living—that won several championships in the Manchester league.

Rich Diamond and three of his friends bought the bar in 1978 and renamed it the Aura Inn ("Aura," he says, is short for "An Unusual Roadside Attraction"). They dispensed with lunch, opened at 4 p.m., and hired loud rock bands. In the early 1980s, DuRussel recalls, the inn was very popular—"There'd be people five deep at the bar"—and too noisy for him to hear customers' orders. "We had to read lips," he says.

With an increased awareness that drinking and driving don't mix, the partygoers have tapered off, and the bar is now more the neighborhood place it once was. The kitchen was closed a lot while Diamond was negotiating a possible sale of the inn. But the deal fell through in May, and Diamond is now reopening the inn as a full restaurant.

—Grace Shackman

Goetz Meat Market

When home was upstairs

In December, the DDA Citizens Advisory Committee hosted a loft tour to get people interested in living upstairs over downtown stores. When Elsa Goetz Ordway was a girl, it was common. From 1905 to 1913, when the Goetz family ran a meat market at 118 West Liberty (now the Bella Ciao restaurant), they were just one of many families who lived downtown where they worked.

Ordway's parents, George and Mathilda Goetz, were born in Wurttemberg, Germany, and came to the United States in 1899. After five years working for a relative who owned a hotel in Niagara Falls, New York, they moved to Detroit, where George Goetz worked as a butcher. A year later they came to Ann Arbor with their sons, Willie and George. They opened the Goetz Meat Market on the street level of the Liberty Street building and moved into the top two stories. Daughter Elsa was born there a year later, with a Dr. Belser in attendance.

The Goetz's family life was intertwined with the store. Mathilda Goetz prepared the family's meals in the workroom behind the shop where her husband made bologna and other meat products. The family's dining room was on the first floor, too, so that they could take care of customers who came in while they were eating. The Goetzes worked long hours—until almost midnight on Saturdays. In those days before refrigeration, people shopped on Saturday night for Sunday dinner. On Sundays the shop was closed, but it was not unusual for a customer to phone and say they were having unexpected company and could they please come over and get some meat?

Ordway's brother Willie, who eventually took over the business, helped his dad make the products then considered standard fare for butcher shops—lard, breakfast sausage, bologna, knockwurst, and frankfurters. Ordway remembers, "My dad would slice the bologna and look at it to see whether it was done right—like a person at a fair looking at cake texture." He made his frankfurters with natural casings, "just so," and was upset when people overcooked them and they burst.

Brother George, in delicate health because of a congenital heart defect (he died at twenty-two), was a photographer. He took pictures of excellent quality despite the slow film and glass negatives then in use. Many of his photos are reproduced today in local histories. He was also knowledgeable about electricity; the family had the first electrically lighted Christmas tree in Ann Arbor. To help his dad, who often carried heavy things up and down the cellar stairs, he wired the cellar lighting to switch on and off when someone stepped on the upper stair tread. When the light began to be on when it should have been off, and vice versa, they finally discovered the culprit: the family cat.

Ordway was too young to work in the store, but she kept busy. She played on the roof of the back room, which was reached from the second-floor living quarters. Her friends in the neighborhood included Bernice Staebler, who lived in her parents' hotel, the American House, now the Earle building, around the corner (Then & Now, May 1993). Riding her tricycle up and down Liberty, Ordway got to know all the store owners, buying penny candy at the grocery store or a ribbon to put around her cat's neck at Mack and Company. She recalls that "an employee of Mack and Company made me a set of large wooden dolls, one of the Ehnises gave me a hand-tooled leather strap for my doll buggy, and Miss Gundert, the principal of Bach School, taught me how to make outline drawings of people and animals when she came to buy meat.

Store owners even knew their customers' pets. Dogs were given free bones, and in those days before leash laws, some came in by themselves to pick them up. Ordway's cat was well known, too - fortunately. As she explains, "One afternoon a customer who worked for the Ann Arbor Railroad came into the store after work and said, 'I see your cat is back.' We hadn't known she'd been away. He told us that he had seen my cat in a boxcar in Toledo and - as that train had been headed for a very distant place - he had carried her over to a boxcar headed [back to] Ann Arbor."

The Goetz family took good care of their customers, too. The meat was never prepackaged, but hung in quarter sections, to be cut to customers' exact specifications. Children who came in with their parents were usually given a slice of bologna. In those days before cars were common, many customers phoned in their orders, which were delivered by the horse-drawn wagons of Merchants Delivery, a company that served the smaller stores that didn't have their own delivery services.

In 1913, wanting a break from the store, the Goetz family moved to a house they had built at 549 South First Street and rented the store out, first to Weinmann Geusendorfer, then to Robert Seeger. They rented the upstairs living quarters to relatives. George Goetz kept a hand in the meat business, filling in at other butcher shops and helping out their owners by making bologna. He also supplied veal to meat markers, traveling around in a horse and buggy to buy the calves from farmers. He died in 1929. Willie, called Bill as an adult, took over the store about 1923. He renamed it Liberty Market and ran it until he retired in 1952. Since then the building has housed restaurants—first Leo Ping's, then Leopold Bloom's, Trattoria Bongiovanni, and now Bella Ciao. The former living quarters are now used as a banquet room (second floor), offices, and storage (third floor).

A return to the practice of living above one's own business will probably not happen in these days of chains, franchises, and large corporations. But the upstairs lofts over downtown businesses can still be made into very desirable apartments. Proponents point out that using downtown's upper stories in this way can keep the area both more vibrant and safer (with more people out and about around the clock). And downtown residents have the advantage of being within easy walking distance of shops, restaurants, and entertainment. Children's author Joan Blos, a member of the DDA advisory council and herself a downtown resident, says of downtown lofts, "Their somewhat eccentric charm appeals to many persons of quite different lifestyles and requirements. Renovated lofts have the potential to provide a useful socioeconomic bridge between the upscale housing of newer buildings and the affordable housing often associated with the downtown area."

—Grace Shackman

Photo Captions:

About 1923, Bill Goetz (far left, next to partner Frank Livernois) took over the former family store and renamed it Liberty Market. He ran it until he retired in 1952; after passin through many uses, the building today is the Bella Ciao restaurant.

Elsa Goetz (later Ordway) about 1910. Born upstairs from the family meat market, she grew up with Liberty Street as her playground. She bought penny candy and ribbons from nearby stores and one of the Ehnises contributed a leather strap for her doll's buggy.

The Village Tap

A local hangout for decades

Eighty years ago you couldn't buy a beer at the Village Tap—then known as Mary's Saloon—because of Prohibition. But in all other respects, the establishment was a bar and a village hangout. Customers would enter through a set of swinging doors, and after passing the candy, tobacco, and ice cream counters in front, they'd find a stand-up bar with a foot rail, surrounded by tables and chairs.

Mary's was named for its owner, Mary Singer. Customers "would sit around kibitzing, smoking a pipe, or chewing tobacco. They'd talk about farming or about old times," recalls Glenn Lehr, who worked there in the 1920s, when he was a teenager. He recalls interesting characters such as Dyke Lehman, who lived three doors north of the bar and hung out there most of the day, going home only to eat meals. Lehman used to tell of the gold rush (Lehr thinks it was probably the one in South Dakota), when he got rich by rolling drunks. "He'd help himself to any cash they had, gold nuggets or coins," says Lehr.

Customers entertained themselves with chugging contests, seeing who could swallow a near beer or a bottle of pop the fastest. (Lehr says he usually won because he had more practice.) They'd play euchre and other card games such as Five Hundred or Pedro. In the winter, people would come in after sledding or ice skating to warm up around the potbellied stove.

The saloon served two brands of near beer, a special brew allowed to ferment only to about 1.3 percent alcohol content; ginger ale, cream soda, and root beer; and soda pop in several flavors like lemon, strawberry, and cherry. Lehr recalls that orange, the most popular flavor, sold more than the rest put together.

Singer sold cheese sandwiches for a nickel and ham or pickled tongue for a dime. Lehr made the last himself, buying tongue from the butcher two doors up, mixing it with wine vinegar, sugar, and onions, and cooking it for four or five hours.

Kids came in after school to buy penny candy and ice cream. Since there were no freezers, the ice cream was delivered in ten-gallon steel containers packed in big wooden buckets filled with ice and salt. It came in three flavors: vanilla, chocolate, and strawberry. Lehr made ice cream bars using skewers borrowed from the butcher. He'd stick a paper cap from a milk bottle on the skewer, add the ice cream, and dip it in chocolate.

Wednesday and Saturday nights, when the farmers came to town, were the busiest times. Lehr was supposed to close the saloon at nine o'clock but usually didn't lock up until closer to eleven. The farmers bought a lot of tobacco. "All the farmers chewed," recalls Lehr. "They would buy ten or more packages at a time. Beech Nut was the favorite." Mary's also sold snuff, sweet tobacco, cigarettes, cigars, and pipe tobacco.

The Village Tap has been owned by the Stein family for the last twenty-five years. Today, brothers Chris and Jack manage it while their mother, Jeanette, enjoys semiretirement. Chris grew up in the bar, learning pool and euchre from customers. He's been there long enough to see people who were brought in by their fathers bringing in their own kids.

The menu has expanded greatly since Mary Singer's day. It now includes a roster of daily specials: soups, goulash, knockwurst, and the burgers for which the place is famous. But just as it was eighty years ago, the Village Tap is a local hangout.

Chris Stein says people often come in after softball, bowling, or golf. Lately, he's been organizing special events, such as the recent Oktoberfest held in the parking lot. "Now that Manchester is a bedroom community, people like a chance to meet," he explains. "Times change, but people are the same."

—Grace Shackman

Photo Caption: Chris Stein and Glenn Lehr.

A tale of two funeral homes

Spite spurred a rivalry that still benefits Chelsea

Chelsea is fortunate that an undertaker's twenty-one-year-old son beat Frank Glazier in the 1893 vote for village president. Otherwise, the town wouldn't have its two respected family-owned funeral homes, Cole and Staffan-Mitchell. Glazier, who later become Michigan state treasurer and Chelsea's most famous business and civic leader, was so enraged at losing to George P. Staffan that he convinced Samuel Mapes, a relative, to give up a successful steam laundry and start an undertaking firm to compete with the Staffan family's.

In the nineteenth century, caskets were made by local carpenters—a number of whom, including Frank Staffan, ended up in the funeral business. Staffan arrived in Michigan in 1847 at age fifteen from Alsace-Lorraine and built many of Chelsea's important buildings, including the township hall, two churches, and many of the downtown shops, using skilled stonemasons from the Eisele and Eder families, whom he had summoned from his native land.

Staffan and his wife, Lena, and their six children lived at 705 South Main and ran their contracting and funeral businesses from their home, as was the custom in those days. Their house still stands, although the stables, a storage building for the carriages and hearses, and the workshop are long gone.

A Democrat, Staffan served on the village council and the township highway and drain commissions. His political involvement, successful businesses, and relationship by marriage to prominent local families such as the McKunes and Keusches made him and his family a threat to Glazier, a Republican businessman with lofty political ambitions. By 1898, at Glazier's urging, Mapes had set up his rival undertaking business right behind Glazier's drugstore at the northwest corner of Main and Middle.

In 1906, however. Glazier undermined his own desire to drive the Staffans out of business when he donated land and money for a Methodist old age home. From that time on, there was plenty of business for both funeral homes, and their rivalry was gradually replaced by mutual respect.

When Frank Staffan died in 1915, the business passed to his son, George P. Staffan—the man who'd beaten Frank Glazier for village president more than twenty years earlier. George P. moved the funeral business to a second-floor spot above a tavern on Main Street, using the space to display caskets and to store equipment for funerals. He made his own embalming fluid, which he sold to other undertakers.

George P.'s son, George L. Staffan, is still active in community affairs at ninety-two. George L. remembers the days when funerals were held in the deceased's home. People usually hung a wreath, called a "door badge," to let people know there was a death in the family. His father would bring a folding couch to the home to embalm the body. The family would pick out a casket, and the Staffans would deliver it to the home. Mourners often put potted palms and a screen around the casket. The Staffans would bring a portable organ and folding chairs for the funeral service.

In the early 1920s the Staffan family moved to a big house at 124 Park that had belonged to a doctor. The former examining room on the side of the house was turned into the funeral office. In 1930 the office was torn down and replaced with a chapel, since by then many people wanted funerals outside the home.

For a time the Staffans also ran an ambulance service, using a converted sedan and their hearses. They often had runs out to the three-lane highway between Jackson and Ann Arbor, where the shared passing lane caused frequent accidents.

George L. Staffan took over the business in 1950 after his father's death. In 1981 he sold it to John and Gloria Mitchell, who had run funeral homes in East Lansing and Rochester. Staffan offered to buy it back if the new owners didn't click with Chelsea, but his generosity proved unnecessary—Gloria Mitchell became so involved in local service projects that she was named the village's citizen of the year in 1997.

The funeral business Frank Glazier instigated also flourished. In 1906 the Mapeses moved to a house at 214 East Middle, using the downstairs for offices and the upstairs for living quarters. A succession of owners sold the funeral business to younger partners—Bruce Plankell, Martin Miller, and Lou Burghardt. In 1977 Burghardt sold it to Don Cole. Cole's son, Alan, and Alan's wife, Wendy, have operated the Cole Funeral Home since 1999. They still run the business out of the house on Middle, although they don't live upstairs.

Recently the Mitchells agreed to a village request that their place be torn down for parking. Gloria Mitchell says the decision was hard, "but now we look back and wonder why the struggle." The new Staffan-Mitchell Funeral Home, less than a mile north of town, has all the latest conveniences, including sound and video systems and a children's play area. Like the founders of the business, the Mitchells live in an attached apartment. Many artifacts from earlier days were moved to the new location. A display cabinet contains such accoutrements of mourning as a vial used to catch a widow's tears, black-bordered handkerchiefs and calling cards, dull black mourning jewelry, and bottles that held George P. Staffan's embalming fluid. And in the garage is an old Staffan horse-drawn hearse. It's occasionally pressed into service, with rented horses, when customers request it.

—Grace Shackman

PHOTOS: FAMILY & HEARSE, CARINE LUTZ; STREET VIEW, COURTESY U-M BENTLEY HISTORICAL LIBRARY

Caption:The Mitchells (above) still have a horse-drawn hearse that can be used for burials, if families request. At one point the Staffan Funeral Home was in a storefront above a tavern on Main Street.

Thriving on the Railroad

Most Washtenaw County towns were founded because of the potential water power nearby. Chelsea, in contrast, owes its existence to the early arrival of the Michigan Central Railroad. When the Michigan Central passed through Sylvan Township in 1841 on its way from Detroit to Chicago, the present site of Chelsea consisted of four small hamlets, each of which had been started in the 1830's. The largest one was Pierceville, founded by Nathan Pierce at the current intersection of M-52 and Old US-12. (Pierce's house can still be seen at 14300 Old US-12.) On the north side of present-day Chelsea, in Lima Township, Nathan's brother Darius had started a town he called Kedron, after a river in Jerusalem. Meanwhile, two other brothers, Elisha and James Congdon, had settled on plots facing each other on either side of the present Main Street. The Congdons, who hailed from Chelsea Landing, Connecticut, called their settlement Chelsea and eventually convinced Darius Pierce to adopt the name for his hamlet, too. In 1848 the railroad built a small station about a mile west of what is now downtown Chelsea. When this station burned down, the Congdons offered free land to the railroad for a new station. In 1850 Michigan Central took them up on their offer, a decision that guaranteed Chelsea's primacy. The same year, Chelsea became a post office, its first store opened, and the Congdons' land was platted. The businesses in the other settlements soon moved into what is now downtown Chelsea. Thanks to the railroad, Chelsea grew and thrived. By 1881, according to Chapman's county history, Chelsea was the largest produce market in the county, shipping grain, apples, stock, and meat, and the largest wool shipper in the state. "With the exception of a day of exceedingly dubious weather. Main and Middle Streets are thronged with farmers' teams," Chapman wrote, "and the stores of these thorough-fares crowded with customers." In 1891, Frank Glazier, son of Chelsea banker George Glazier, started manufacturing oil heating and cooking stoves in two buildings on Main Street. After a disastrous fire, he rebuilt on land north of the railroad station. He built on a grand scale, and the stove works' red-brick clock tower remains Chelsea's best-known landmark. Also active in politics, Glazier rose to become state treasurer, but was forced to resign in 1907, when it was revealed that he had deposited state money in his own bank and had pledged the same stove company stock as collateral for loans all over the state. His company went bankrupt, and Glazier served two years in prison for misusing state funds before returning to Chelsea to live out his life on Cavanaugh Lake. Until ten years ago, Chelsea still had a small-town feel, with the stores on Main Street serving residents' everyday needs. But with the opening of a shopping center at M-52 and Old US-12, downtown stores started moving there, returning full circle to the original site of Pierceville. Almost overnight, downtown Chelsea became a more upscale regional shopping and entertainment area: The Common Grill restaurant replaced Dancer's, the quintessential small-town clothing store, and local son Jeff Daniels opened his excellent new theater, the Purple Rose.