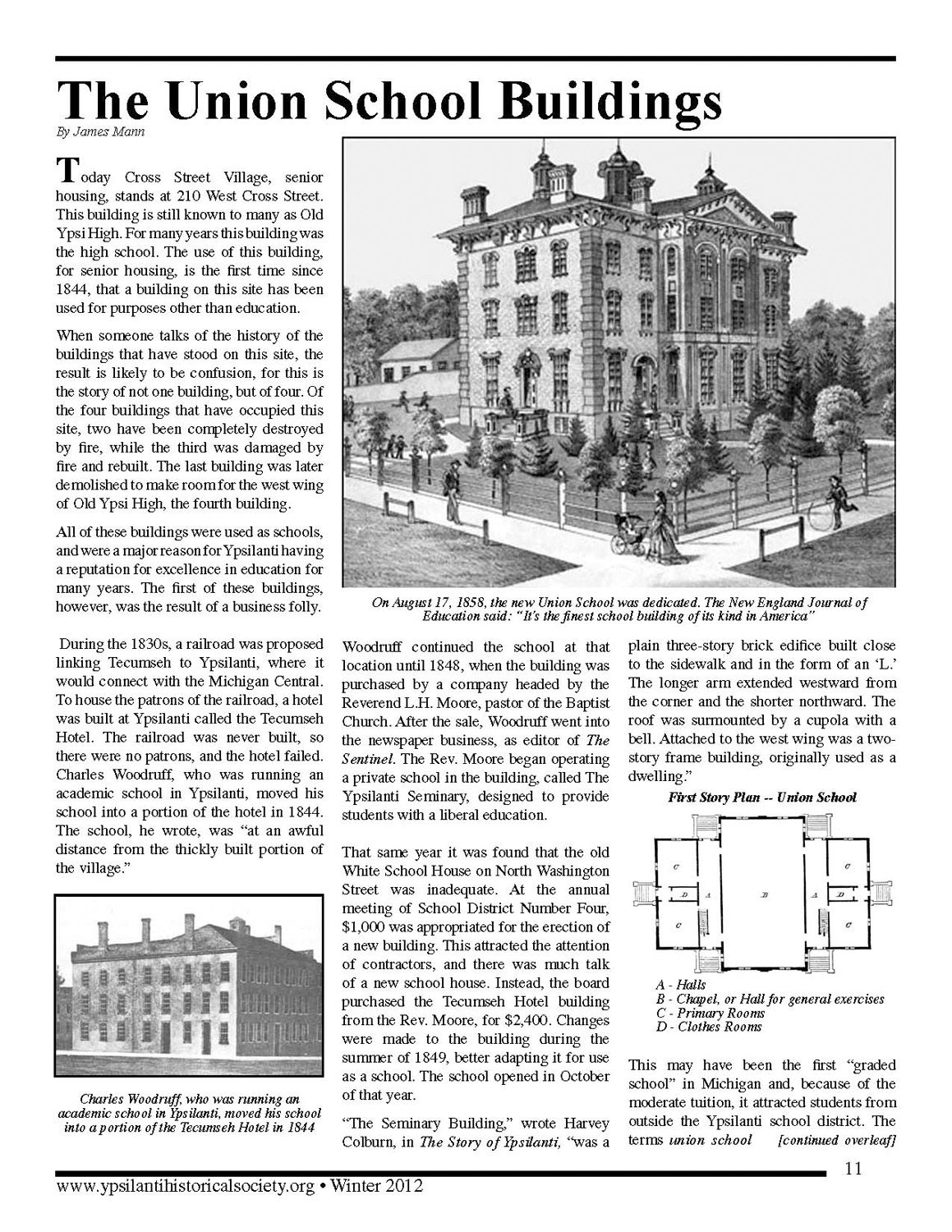

A Piece of Henry Ford's Dream

Phoenix Packaging has revamped his one-room Saline schoolhouse.

Henry Ford knew how to run a car company, and he thought he knew how to run the country. In his view, the rural values of his childhood, including education in a one-room schoolhouse, represented America at its best.

In 1935 Ford turned Saline's Schuyler Mill, on Michigan Avenue, into a soybean processing plant. Soon after, he moved a dilapidated old school from Macon Road to a site directly across the street. He intended it for the children of the men who were producing plastics and paints at the restored mill (today Wellers' banquet facility).

Ford spared no expense to restore the school, complete with cloakroom, potbellied stove, and two-person desks. He even installed two outhouses (modernized with real plumbing and heating). On September 7, 1943, Ford attended the opening of the school.

Many of the thirty-five students, who ranged from kindergarten through eighth grade, had tenuous connections to Ford, or none at all. Allen Rentschler's father was farmer, although his uncle, Carl Bredernitz, worked at the soybean factory. Bob Cook's father was a Chevrolet dealer. Thelma Wahl Stremler's dad worked at Bridgewater Lumber.

Like the physical structure, school ac- tivities were a mix of modern and old-fashioned. "We had the latest books, the latest teaching methods," recalls Cook. The older children often served as teacher aides. "I helped the younger ones read, but I felt I was just having fun," remembers Stremler.

Each day started with a chapel service that included recitations by students and hymns led by Stremler on the piano. At recess children of all ages joined in games such as kickball and softball. Ford furnished the school with looms of various sizes.

For students and parents, one attraction of the school was free medical and dental care. Both Rentschler and Stremler got their first eyeglasses thanks to Ford.

The Saline school was one of several Ford built near his small plants. Don Currie, the first teacher, moved on after a year to become principal of Ford High School in Macon. Clare Collins, later a shop teacher at Saline High School, took over from Currie.

The one-room school didn't last long. In 1946, Ford, in failing health, decreed that all his schools would close at the end of the semester. The students returned to public schools; they had little trouble adjusting. Ford died a year later at age eighty-three.

The Saline public schools were not interested in the building, so it was sold to Elizabeth and Bruce Parsons. The Parsonses moved the entrance to the side, added a two-story wing with four bedrooms, and divided the schoolroom into a kitchen, dining room, and living room.

By 2002, when Patricia and Chris Molloy bought the building, a series of owners had let it deteriorate. The Molloys wanted to turn it into an office for their company, Phoenix Packaging. After some negotiations with the city, the Molloys agreed on a historic-preservation easement in exchange for business zoning. In the future, the exteriors of the buildings may not be altered without the city's permission.

The Molloys carefully preserved and restored what was left of the original school, including the hardwood doors, floors, and wainscoting. The first floor is their office; they rent the upstairs to attorney Russell Brown and a separate shed to architect Dan Kohler.

The Molloys have a collection of Ford School pictures on the wall. They acquired an old potbellied stove but then learned that the Saline Area Historical Society has the school's actual stove. The Molloys have agreed to a swap. Now they are keeping their eyes out for one of the old two-seater desks.

—Grace Shackman

Re-creating the Rentschler Farm

Setting the clock back a century

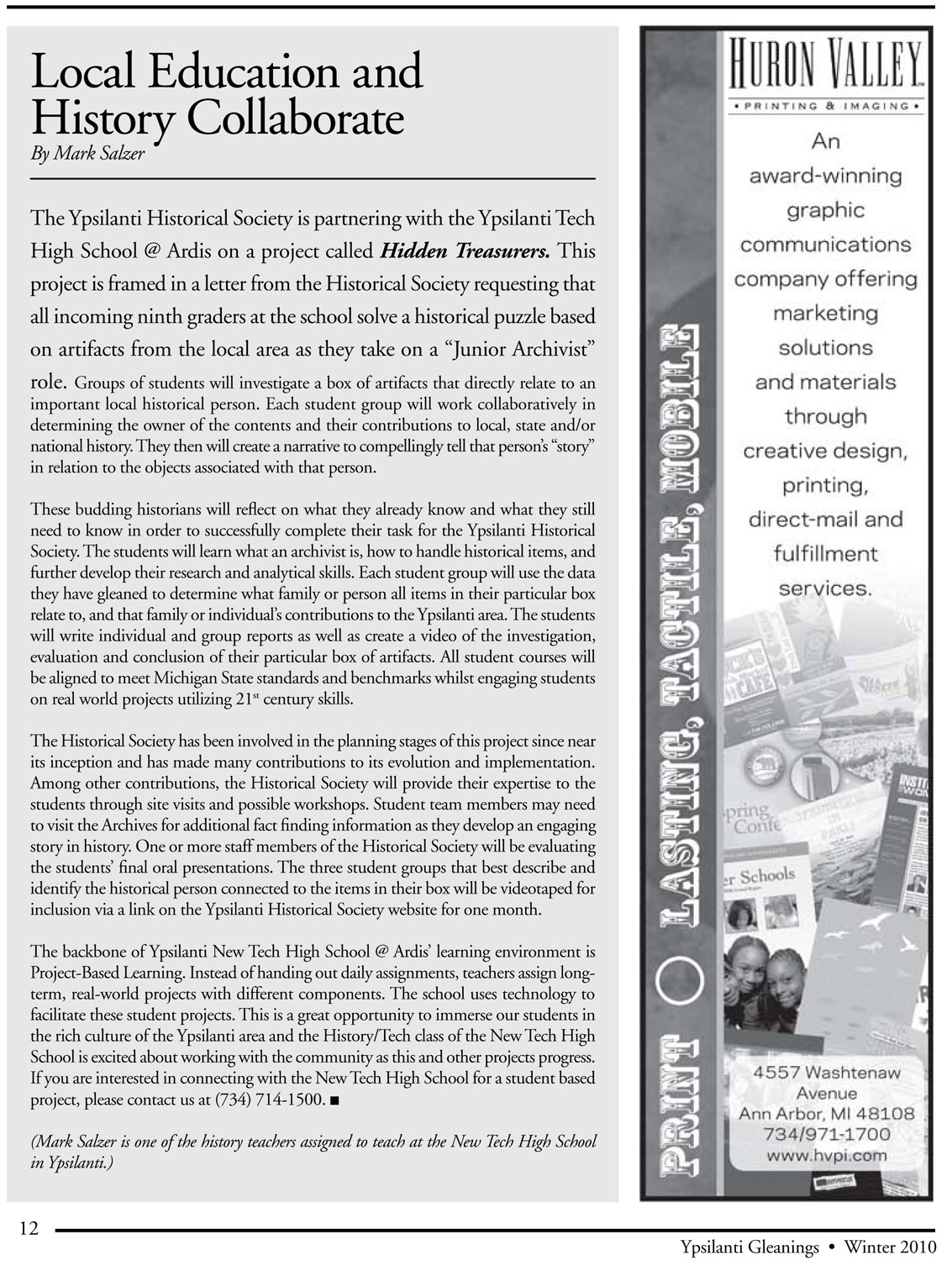

Enthusiastic and knowledgeable volunteers are transforming the Rentschler farm on the edge of Saline into a teaching tool. They're restoring the house to show how a farm family lived at the beginning of the century, bringing in livestock to demonstrate the working of the farm, and re-creating a kitchen garden to teach children how to grow plants—all with the unusual advantage of having the last owner of the farm nearby to answer questions.

The farm is on Michigan Avenue, just east of the Ford plant. It was built in 1906 by Matthew Rentschler on 216 acres that his brother, Emanuel, had bought two years earlier. The land would eventually be farmed by three generations of Rentschlers.

The last was Warren Rentschler, who lived on the farm almost all his life. "We had sheep and chickens, sold eggs at the door, had pigs; we grew corn, hay, wheat, oats," Rentschler says. "We sold hay to the horse trade."

As the city of Saline crept up to the farm, Rentschler gradually split parcels off and sold them, starting with a field for the Ford plant in the 1960s. A few years ago, then-mayor Rick Kuss heard that Rentschler was about to sell the last of his farm to Farmer Jack for a shopping center. Kuss talked to him about selling the house and outbuildings to the city instead.

Rentschler was delighted with the idea. In spring 1998 the city of Saline bought Rentschler's property at a discount, and the Saline Area Historical Society went to work at the farm right away.

The restoration of the house's interior is being organized by Janet Swope, antiques dealer, teacher of antiques classes, organizer of the Saline Antiques Fair, and former owner of the Pineapple House. Swope's plan is to restore the home to the way it looked between 1900 and 1930. "We may have some older things," she says. "People inherit things. But we'll have nothing newer than 1930."

Her goal is to "restore it to what a farmhouse would be like—not real affluent, middle class, but nice." This winter she hopes to finish the downstairs rooms: the master bedroom, dining room, and parlor. If time allows, she and her fellow volunteers will also work on the hired man's room upstairs. The master bedroom will be decorated with a historic Saline wallpaper design, found in the Bondie house on Maple, that's being reproduced by the Thibaut wallpaper company. Next spring, Saline resident and former county clerk Bob Harrison plans to re-create the front porch, using a 1910 photo for guidance.

Cathy Andrews, master gardener and historic furniture restorer, created a kitchen garden with help from area schoolkids. She laid out the beds in long, narrow rows, as the Rentschlers would have in the 1930s, and planted vegetable and flower species common for that period, such as a tasty, pinkish beefsteak tomato and a very red variety developed at Rutgers University that was considered good for canning. She kept the rhubarb and horseradish she found at the farm.

Rick Kuss and Jeff Hess, among others, are tending the animals already housed in the outbuildings. Roosters, ducks, and pigeons were donated from Animal Rescue, while Domino's Farms provided two miniature goats. A local farmer gave two piglets, which have since grown big enough to knock Kuss down. "I liked them better when they were babies," he jokes.

Wayne Clements, president of the historical society, bought two lambs for the farm at the 4-H fair. Others followed his example and began donating their prize lambs to the farm to save them from slaughter.

Today, Warren Rentschler lives on the north side of Saline. What does he think of what's happening at his old farm?

"I like it fine," he says. "They'll preserve it. Who wouldn't want that? My granddad and dad worked so hard to keep it up, and I spent a bit of time too."

—Grace Shackman

Photo Caption: Elizabeth and Emanuel Rentschler with their children. Alma, Alvin, & Herman, in front of their farmhouse around 1910.

Memories of the One-Room Schoolhouse

Reading, writing, and getting along.

The idea of the rustic one-room schoolhouse looms large in the American imagination, calling up images of kids with cowlicks seated in rows at sturdy wooden desks, all eyes front on the teacher whose homespun brand of tough love taught them everything from penmanship to good posture. But for almost everyone who lived on a farm in Washtenaw County before World War II, the one-room schoolhouse is not a romantic legend but a centerpiece of their personal history. Many residents still remember fondly the experience of attending one of the roughly 150 one-room schools in the area.

Graduates of one-room schools tend to forget or gloss over their limitations, which to modern sensibilities were considerable: walking long distances, enrollments so small that a student might be the only one in a grade, lack of supplies, and no electricity, running water, or telephones. Instead, they remember what is arguably more important—the personal benefits of learning how to work together and the lifetime friendships such schooling fosters. Says Taylor Jacobsen (Lodi Plains, 1946-1950), "Anything I lost out on I gained in other ways—the camaraderie of the kids, a way of listening, doing chores, being part of that thing." Marge Hepburn, who attended Canfield (1938-1939), liked school so much that she insisted on going even in terrible weather. "I had wonderful times at school," she recalls. "One bad winter day, the teacher didn't come, but the kids all showed up." It was so cold that day that Hepburn remembers having to stop at a neighbor's house to warm up before making it all the way home. Another former student, Billie Sodt Mann (Pleasant Lake, 1922-1931), puts it succinctly: "All I can say is I loved it."

The one-room schools operated under an 1869 state law that mandated free education for all, paid for by taxes. (Previously, parents had paid tuition based on the number of days their children attended school.) A 1915 county map shows 140 one-room schools; the number evidently grew slightly after that date, to about 153 schools between 1926 and 1939. School districts were small enough that students would not have to walk more than a few miles to school, and were adjusted periodically to equalize the number of students.

Most one-room schools enrolled fewer than twenty students, sometimes all from just a few large families. Rarely were there more than two or three in a grade, and some grade levels might not be represented. Marge Hepburn, for example, was the only student in her seventh- and eighth- grade classes at Canfield, while Jean Eisenbeiser Schmidt was one of three (the two others were boys) in her fifth- and sixth-grade classes there. (Before Canfield, Schmidt also attended North Lake,1934-1936.) Similarly, Billie Sodt Mann was the only one in her grade at Pleasant Lake, while Lenora Haas Parr and Ruth Weidmayer Kuebler were the only two in their grades there from 1924 to 1933.

Schools were built near the center of the district, on land that was given or lent by farmers. Residents elected a school board that ran the school, seeing to its construction and maintenance and providing materials. (The first schools were usually wood-frame buildings, but they often were replaced with brick schoolhouses when the community became more established.) The school would typically be named after the site's donor in a symbolic gesture of thanks; if the farming community went by a particular name, such as Pleasant Lake or Lodi Plains, that became part of the school name as well.

Women of many talents

School boards were also responsible for hiring the teachers and setting their salaries. Indeed, the success of one-room schools depended largely on the teachers, mostly women, who were called on to do everything from tap dance to stage manage to umpire, creating a safe and supportive home-away-from-home for countless children whose parents were hard at work in the fertile fields of the county.

Generally, the rural schools could not afford to pay salaries as high as those at the town schools (the school board's appropriation was based on the number of students), and the qualifications to teach were not as high. Jane Schairer, who taught at Freer School in Lima Township from 1944 to 1947, was hired after completing two years at Michigan State Normal College (now EMU) with a limited certificate qualifying her to teach in rural schools. In the early days of one-room schools, salaries were so low that teachers often had to board at their students' homes, like Laura Ingalls Wilder in These Happy Golden Years. By the twentieth century they were paid enough that they could live on their own. Young teachers often got their start in one-room schools, before moving to a more remunerative assignment or leaving to get married.

But others made a career out of teaching at a particular school, perhaps because they themselves were from the area or just because they loved the work. Although rural teachers needed less training than their urban counterparts, they had to be well versed in every subject, play the piano, keep a diverse group in order, and be able to juggle many assignments at once. Even with all the material a rural teacher had to cover, the classes were small enough that she or he (although way out-numbered, male teachers did exist) could tailor the curriculum to make sure mat no one got left behind and that quicker students could move ahead.

Jean Schmidt, for example, started kindergarten with two boys who were not as interested in reading as she was, so her teacher let her do the first-grade work, and the next year she moved into second grade. George Brassow (Lodi Plains, 1934-1943) was the only one in his eighth-grade class, so he moved at his own speed and finished all the work by February. (He stayed home the rest of the term, working on his family's farm.)

If a teacher had special interests or talents, she could share them with her students. Brassow and Mary Anne Groeb Hanselman (1933-1943) recall with appreciation one Lodi Plains teacher, Gertrude Kromer, whose skills included writing school plays and tap dancing. Although gym wasn't part of the curriculum, she used to lead the class in exercises. "She had a great disposition. She never came unglued," recalls Hanselman. Barbara Wing (Peatt 1932-1935, Arnold 1937-1941) had a Mrs. Engle, who was very good at teaching reading. She later became a reading specialist in the Dexter schools.

Taylor Jacobsen had a teacher named Phoebe Summerhill. "She noticed I had a flair for art, so she would get out the chalk and have me draw. She wasn't an art teacher, but she did what she could," says Jacobsen, who recently retired after nearly forty years as a high school art teacher. Summerhill also convinced her landlord, Art Miller, to help teach shop and also to ump for softball games. In quiet moments she would regale the class with stories of the copper country in the Upper Peninsula. "I thought she was a terrible woman, strict—she made us do our lessons. But as I got older, I understood how wonderful she was," muses Jacobsen.

Although many teachers were wonderful, some weren't. "I heard of a few teachers who didn't do much," says Jacobsen, while Schairer admits, "If the teacher was not good at music or art, it was unfortunate."

Making the grade

Preview and review were the cornerstone of the rural schools' educational philosophy. Students were called up grade by grade to recite their lessons while the rest of the children sat at their desks working. "You sat in the same room with classes of different grades—you heard what was coming up," recalls Parr. "If you didn't get it that time, you got it another time," explains Hanselman.

The curriculum included basic subjects such as history, geography, reading, and math, as well as those - penmanship, for example - no longer emphazised. "If you didn't learn anything else, you learned penmanship and spelling," says Hanselman. Kuebler recalls that her teacher set aside a time, maybe once a week, to observe all the students' penmanship. "She'd walk around as we were writing and told us how to sit, how our postures should be."

Reading instruction included recitation. "Everyone teamed to read out loud. You couldn't use your finger—you had to do it with your eyes," recalls Hanselman. Spelling was made more fun by periodic spelling bees. Several of the winners report that they still own the dictionaries that the Detroit News awarded to them. Brassow recalls similar special events related to math.

Although science was not listed on the 1935 report card, a subject called "agriculture/nature study" was. Several students remember that agriculture, taught in seventh and eighth grade, included how to grow crops such as wheat, corn, and oats. Informal opportunities for nature study abounded. "As we walked to school, we heard the bobolink and meadowlarks from cow pastures," recalls Jacobsen. "Walking to and from school we'd notice nature much more than [we would have] in a bus," adds Hepbum, remembering how in the spring she and other students would scoop up frog eggs in a marsh behind the school.

Students and teachers alike went beyond the boundaries of their schoolroom in other ways, too, driven by necessity and invention. There was no such thing as a school janitor, for example, so the teacher, or sometimes a school board member who lived nearby, came early to feed the wood-burning stove. Older kids helped keep it going and banked it at night. Students hauled water from a neighbor's pump. At the end of the day, students cleaned the blackboard, pounded the erasers, and swept the school.

And just as everyone worked together, the students all played together, too. All ages and sexes were welcome to join recess games, since everyone was needed to make up teams. They played games that needed little or no equipment, such as fox-and-hounds, blindman's buff, hide-and-seek, and Annie-over, a game that involved throwing the ball over the schoolhouse, essentially using it as a net.

Girls played softball. George Brassow recalls, "It wasn't known as coeducation. We just said, 'We've got five girls on our team—they're pretty good.' " At Pleasant Lake, even the teacher joined in.

Students also came together for special events. Every school had a Christmas program involving all the children in recitations, songs, and pageants. For performances, most schools improvised to create a stage within the schoolroom. Pleasant Lake, however, had a real stage, complete with curtain and dressing area: Mann's father, Manny Sodt, was proprietor of the Pleasant Lake House tavern and let the students use his place. Other events varied from school to school. For instance, when Schmidt was a student at North Lake, the students had a pet show. "I rode my pony to school. Everyone brought pets," she recalls, noting that were a few dogfights as a result.

For the kids themselves, however, discipline was rarely a problem. "We were all good kids—we didn't have anything to get in trouble with," recalls Mann, although she admits a couple of boys liked playing tricks such as sticking their feet out in the aisle to make girls trip. Schmidt recalled a boy bringing in a blue racer snake that he had killed on the playground and putting it around a girl's neck, causing her to scream. Hanselman recalls that one Halloween students balanced the teeter-totter boards on the roof of the school.

In spite of such minor diversionary incidents, students attending the one-room schools did well overall academically. An elected county commissioner of schools oversaw the rural schools, trying to maintain high standards so that all students received a good education. Cora Haas, Washtenaw's commissioner of schools from 1926 to 1939, supervised all the teachers, making unannounced visits to each school twice a year. Her assistant, Mildred Robinson, also made frequent visits to assist teachers.

At the end of the school year, schools administered the same sealed tests across the county. Rural seventh- and eighth-graders went into Ann Arbor to take more comprehensive tests and then enrolled in high school if their parents could afford it. (During the Depression years, some children were needed to work on the farm and had to quit school after eighth grade to help support their families.)

The county's attention to maintaining standards paid off. Those who attended one-room schools report having no trouble academically when they moved on to city or village high schools. It was not unusual for valedictorians and salutatorians to be country school graduates. But it was often hard to make the social adjustment. "It was scary," admits Mann, who had limited contacted with the world outside her immediate community before starting high school in Manchester. "If we got into town it was a miracle. My folks had a store, so we never had to go shopping."

Rural schools were communities within themselves; for most of the year they were quite isolated. In the spring they might sometimes go a little farther afield by challenging nearby schools to baseball games. "It would be another nation—the school four miles down the road," recalls Jacobsen. Joyce Boyce (Arnold 1935) remembers that one year there were only nine students in her school, all girls, but they still challenged nearby Spiegelberg School to a baseball game. "We didn't do so well—we were all girls—but it was good to get acquainted," she says. Brassow remembers having track meets with Dold, the school just north of Lodi Plains.

The village schools were much bigger by comparison (though still small by today's standards). Boyce recalls there were twenty-one in her Dexter High graduating class. Jacobsen found the biggest challenge was in athletics. "The city kids played basketball in junior high. I was like a boat out of water."

Postwar consolidation

After World War II the country schools began consolidating with those in the closest villages. Their populations were decreasing as people left farming, but consolidation efforts were usually set off when a village high school became over-crowded and village residents wanted a larger tax base to build a new school. Consolidation was decided by elections in each country school district and was often hotly contested. Parents feared loss of local control, higher taxes, and long, tiring bus rides for their children. On the other hand, larger schools could offer many more amenities such as gyms, shops, science labs, and home economics rooms, plus more highly trained teachers.

After consolidation it often took years to untangle the legal status of the abandoned buildings and the land they stood on—to determine whether the site had been formally given to the school district or just used by tradition. In the former case, the building was sold, with the money going to the consolidated school district. In the latter, it reverted to the family of the farmer who had lent the property.

Today, most of the schoolhouses have been torn down or converted to homes. Surviving buildings have often changed so completely that it is hard to recognize their original use. Canfield (Lyndon Township at Waterloo and M-52), Pleasant Lake (Freedom Township on Pleasant Lake Road), and Lodi Plains (Lodi Township on Ann Arbor Saline Road at Brassow) have all been torn down. North Lake (Dexter Township at Hankerd and North Lake roads) was used for a while as a Boy Scout lodge, and Peatt (Webster Township on Gregory at the end of Vaughn) was used as a pigpen, but both have also been torn down. Arnold (Dexter Township, Island Lake Road) and Dold (Lodi Township, 3481 Ellsworth) have both been converted to homes. Other uses include church offices (Webster Church on Webster Church Road) and nursery schools (Beach on Chelsea-Dexter Road and Stone School on Packard in Ann Arbor).

Washtenaw County has two school museums and will someday have at least one more. The 1895 Town Hall School was moved to the EMU campus from the corner of Morgan and Thomas roads in Pittsfield Township. Podunk School, circa 1850, originally on Walsh Road, has been moved by the Webster Historical Society to Webster Church Road, near the society's other historic structures. The Saline Area Historical Society plans to move Blaess School on Gensley Road after it completes other projects. These three surviving structures together stand as a symbol of the kind of education whose lessons last a lifetime—an educational experience that alumnus Taylor Jacobsen describes simply as "a gem."

Educate us!

Our local history expert, Grace Shackman, tells us there are many more former one-room schoolhouses out there than the five she describes in this article. "Some of them have probably been converted to houses or moved.'' she explains. We're inviting our readers to help us find them. It you know about any old one-room schoolhouses in the area served by the Chelsea, Dexter, Manchester, and Saline post offices, let us know at Schoolhouse Contest, Community Observer, 201 Catherine Street, Ann Arbor. Michigan 48104 (fax: (734) 769-3375; e-mail: mike@aaobserver.com). Whoever finds the most and can offer some proof of each building's former status as a schoolhouse will receive a $25 gift certificate to any business advertising in this issue. (In the case of a tie, there will be a random drawing.) We'll publish a complete list in our fall issue. So take some leisurely drives out in the country this summer - you've got till August 24 to tell us what you find.

Photo Captions:

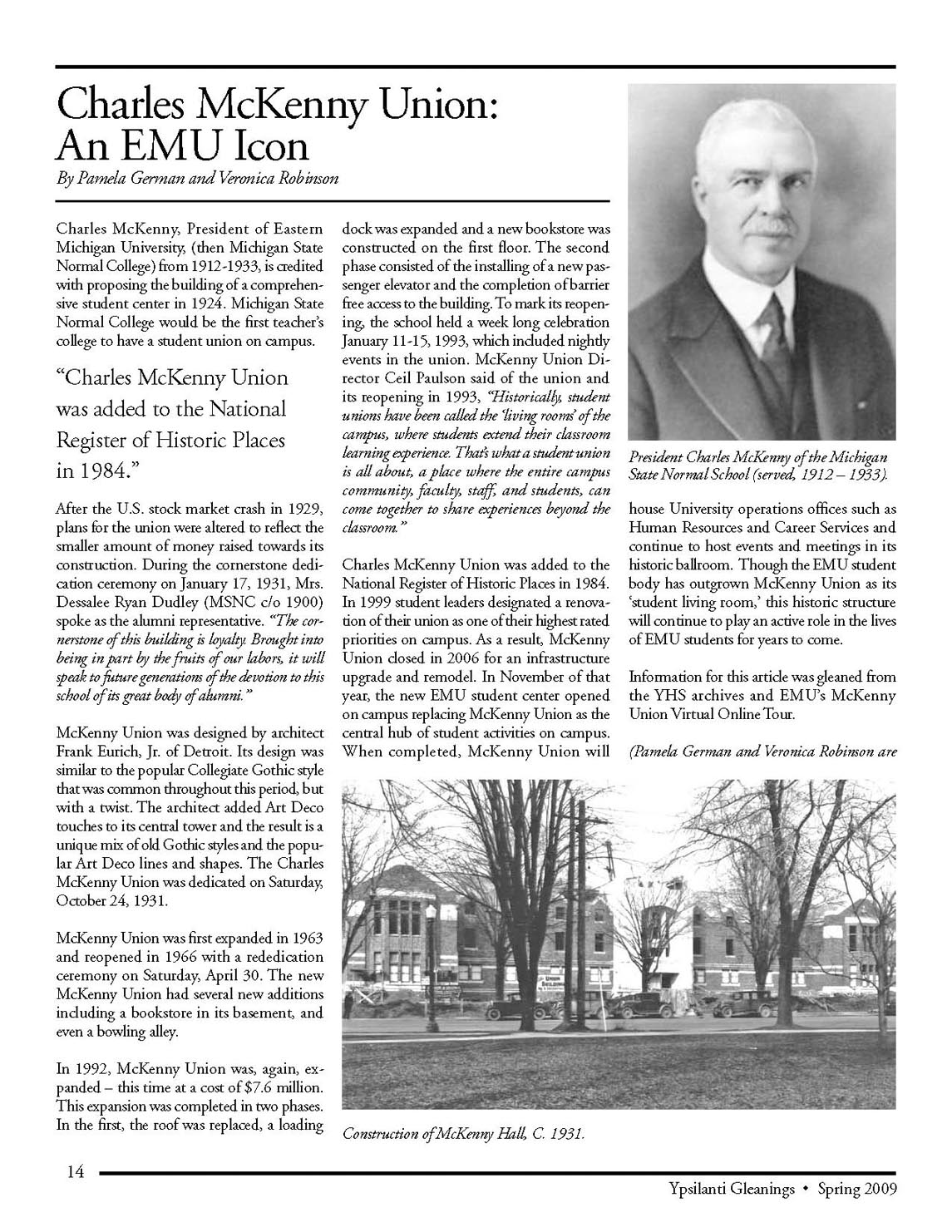

Mclntee School in Lyndon Township, built 1888. Older students helped teachers tend wood-burning stoves like the one in this 1900 photo.

Memories of St. Mary's

The old parish school thrives as Chelsea’s arts center

A stairway to the sidewalk on Chelsea’s Congdon Street is all that’s left of old St. Mary Catholic Church. The church rectory and convent are now private homes. The parochial school building, however, still resonates with art and music, as it did in the days when Dominican sisters ran the place: it’s now the home of the Chelsea Center for the Arts.

St. Mary School was a center of activity from 1907 to 1972. Passersby at recess time could see children climbing on playground equipment, playing baseball in an empty field behind the church and rectory, and enjoying marbles and other games in an area blocked off by sawhorses on the street.

Ann Arbor’s Koch Brothers constructed the two-story brick school. Its first students were mostly descendants of Irish immigrants who had fled the potato famine and of Germans from Alsace-Lorraine who had come to avoid serving in Napoleon III’s army. Father William Considine, who started the school, was a good friend of Frank Glazier, Chelsea’s leading citizen. At Considine’s behest, Glazier, a Methodist, spoke at the school’s opening in January 1907.

The school had four classrooms on the first floor and an auditorium on the second. Originally it housed only grades 1 through 8, but in 1909 a two-year commercial course was added, which turned into a four-year high school in 1916. Six women enrolled in the first commercial course, and two students made up the first high school graduation class. During World War I classes were moved into the convent because there was not enough coal to heat the school.

The school’s auditorium included a stage, an orchestra area, and dressing rooms. The school regularly produced concerts, recitals, and plays. A 1917–1918 St. Mary’s musicale program listed thirty-two student numbers; the instruments included violins, cornet, bells, drums, and piano. Several times a year students put on plays or pageants, and not always on religious themes. The hall was also used for church and community functions and as a gym.

John Keusch, a 1927 graduate, recalls shooting baskets at recess, after school, and at night. Some parishioners complained about the cost of lighting the gym at night, but the parish priest at that time, Father Henry Van Dyke, was an ardent supporter of athletics. A former student remembers him watching a baseball game out his window. “The bell rang and they started to come in, but he called out that they should finish the game,” she recalls.

Keeping the gym open at night paid off. In 1923 a team composed mostly of St. Mary’s students won a state basketball championship. In 1925 an official St. Mary’s team won the class D title. The next year the team, with an added member from Chelsea High School, won a three-state tournament sponsored by the Ann Arbor YMCA. St. Mary’s also had an excellent girls’ basketball team that often accompanied the boys to out-of-town games and played against girls from the competing school.

These victories, especially the 1925 championship, were remembered and celebrated for decades. When Rich Wood attended St. Mary’s in the 1950s, the winning teams’ pictures were still hanging prominently on the wall, and students knew which classmates’ fathers had participated.

The 1925 basketball triumph was especially memorable, since it came on the heels of a fire that destroyed the school on February 6. Keusch recalls, “I had been there that evening practicing basketball until nine or ten. I was woken up at one when the fire whistle blew.” He rushed over from his house. “The volunteer fire department all came out, but they couldn’t save the building,” he remembers. All that was left was the foundation and some walls.

After the fire, classes moved to the church, with groups gathering in separate corners. The younger students sat on the kneelers and used the seats of the pews as desks. The basketball team practiced and played games in the Glazier Stove Company Welfare Building’s unheated second-floor gym.

Within two days of the fire, farmers came with teams of horses, pushed down the walls, and cleaned up the debris. Detroit architect William DesRosiers designed a new building, which was constructed by Detroit builder George Talbot, who had a summer place at Cavanaugh Lake. Keusch, then fifteen, worked as a mason’s assistant that summer. By November the building was ready for use.

The new school was built on the same foundation but had only one floor. An auditorium was added to the side of the building. It was named after one of St. Mary’s first graduates, Herbert McKune, who was killed in World War I. (McKune also gave his name to Chelsea’s American Legion post.)

The basement served the social functions of the hall. It had a full kitchen where food was prepared for Altar Society dinners, fish fries in Lent, and other events. At Thanksgiving “feather parties,” parishioners played keno to win live turkeys and chickens.

In 1934, in the midst of the Depression, the high school closed. Four seniors graduated that June, and the next year the rest went to the public high school. A student recalls that the move was traumatic: “We couldn’t remember not to stand up when the teacher called on us. We were trained to stand up and say ‘No, Sister,’ ‘Yes, Sister.’ The kids made fun of us and did things like put gum on our seats.”

Pat Dietz, who went to elementary school at St. Mary’s in the late 1930s, recalls that she was petrified attending the public high school. “It was a whole new challenge,” she says. “St. Mary’s was so much smaller.” But she found the sisters had prepared her well, especially in math, penmanship, and grammar. A generation later, in the late 1960s, her son Todd Ortbring also found he was ahead academically, especially in subjects that were conducive to rote learning, but public school was “a major cultural shock. The girls wore miniskirts and the boys bell-bottoms, and they all talked about music, drugs, and sex.”

In the 1960s, as nuns became scarcer, lay teachers were increasingly employed at St. Mary’s School. In 1968 seventh and eighth grades were discontinued, and in 1972 the school closed. One sister stayed on to teach religious education, and the hall continued to be used for functions such as wakes.

In 1998 Jeff and Kathleen Daniels bought the school to use the hall as rehearsal space for the Purple Rose Theater. Since they didn’t need the rest of the building, they sold it to the Chelsea Center for the Arts for $1. The center, founded in 1994, offers adults’ and children’s art and music classes as well as revolving art shows. A nonprofit group, it raises most of its funds at an annual autumn jubilee.

“It was one of my life’s blessings that I was able to attend the school under the Dominican sisters,” says Keusch, adding, “They would be proud of the present use of the school building.”