A Century at State and Huron

A Century at State and Huron

The Union School and Ann Arbor High were once the city's pride.

Ann Arbor's first public high school opened on October 5, 1856. Known as the Union High School, it stood on State Street between Huron and Washington. Destroyed fifty years later in a spectacular New Year's Eve fire, it was replaced by what is now the U-M Frieze Building—a structure that many Ann Arborites of retirement age still think of fondly as Ann Arbor High.

Earlier this year, the regents voted to demolish the Frieze Building to make room for a new dormitory, consigning to memory the public schools that occupied the site for a century. But the hopes and headaches that surrounded their construction remain surprisingly current today.

The path to the Union High School was tortuous, slow, and often contentious. At least fifteen communities — from Flint to Tecumseh —opened public high schools before Ann Arbor did. The reasons for the delay were timeless: money and politics: Ann Arbor's first schoolhouse, built on land donated by village founder John Allen, opened in September 1825. By 1830 the township of Ann Arbor was divided into eleven school districts, with District 1 including the village. The first report of District 1's commissioners, in 1832, summarized the situation briskly: "No. of children between 5 and 15 years of age in the district, 161. Average No. in school, 35. No public moneys received."

Support for publicly funded education was slow to develop. Many residents, especially the wealthy who could afford private schools, opposed any tax for operating public schools. As a result, complained the Michigan State Journal in 1835, "a neglect of schools has become almost a proverbial reproach upon our village."

The situation was complicated by the multiplicity of school districts. By 1839 the eleven districts of Ann Arbor Township had been consolidated into four, and in 1842 those were consolidated into one. But in the 1881 History of Washtenaw County, Michigan, W. S. Perry, superintendent of schools from 1870 to 1897, records that in 1845, "a petition, which secured the names of nearly all the solid men of the town north of Huron St., the aristocratic part of the village, was presented to the school inspectors, praying them to divide the districts 'before any expenses incurred in preparing to build a mammoth school-house, as we prefer the system which experience has proved to the visionary and costly experiments.' Counter petitions of those living in the south and west portions of the town were made, but nevertheless the division was made, and for eight years the town supported two schools and two sets of officers throughout."

The two school districts were finally unified in November 1853. Within days, a committee was appointed to develop plans for the "Union School." By the end of December, the school board had decided on a site—one and three-fifths acres, bounded by Huron, State, Washington, and Thayer streets. The property, owned by Elijah W. and Lucy Morgan/cost $2,000.

The board presented plans and construction cost estimates for the building at a public meeting on February 4, 1854. After a long and vehement debate, it was resolved "that the District Board be, once it is hereby authorized and directed to erect and furnish at the expense, and on the faith and credit, of this District, a brick building for a Union High School."

The board voted to raise $10,000 by tax to cover the anticipated cost. "We do not like to pay taxes better than others, but when we know that we are paying for school purposes the money goes freely and without regret," the Michigan Argus editorialized. "We must have good schools or big jails."

The Morgans' land was on the extreme eastern end of the village—so far from the center of town that it had been used only for pasture and the occasional circus performance. But once the school was sited, development soon followed. "Many new houses are being built and yet the demand is not supplied," the Argus reported in September 1857. "People are moving here to take advantage of the University and our model Union School."

In its haste to get the school under way, the board had badly misjudged its cost. In addition to the $10,000 voted at the meeting in February 1854, the Argus reported in September that a "tax of $7,000 was voted to be raised the present year, and to be appropriated toward the erection of a new School building. A tax of 70 cents per scholar was voted for School purposes, and other small amounts for contingent expenses."

The following January the Argus reported on a bill, just passed by the Michigan Legislature, that seems to have been aimed at removing all possible obstacles to progress on the building. The legislation gave school boards the "power to designate sites for as many school-houses, including a Union High School? as they may think proper, by a vote of two thirds of the legal voters present, at any regular meeting." Boards were also granted the power to purchase land, raise taxes upon property within the district, fix tuition for nonresident scholars, make and enforce bylaws and regulations, borrow money, and repay loans.

Ann Arbor's board now could proceed in the knowledge that its actions bore legal sanction—a timely reassurance, as construction funds were once again found insufficient. In addition to the $10,000 voted in February 1854 and $7,000 in September of the same year, a meeting in September 1855 authorized borrowing $10,000, bringing the total appropriation for the building to $27,000. The following January, another public meeting approved borrowing a final $8,000 to complete and furnish the building and fence and grade the grounds.

School records do not provide a total cost figure for the building.

However, from 1855 through 1863 the district issued 167 individual bonds, ranging in value from $50 to $1,100, and totaling $32,637.50. That matches closely with the expenditure figures given in the Argus, which add up to $35,000—more than triple the original estimate.

For its money, though, the city got a show-place—a building a railroad publication called "the crowning glory of the town." Built of brick on a fieldstone foundation, the handsome Italianate school stood three stories tall, set well back from the street, with a curving driveway in front. The third floor was one huge assembly hall, used for public gatherings of all sorts, including the U-M graduation exercises. The basement, wrote the state superintendent for public instruction, "contained living quarters for a janitor and his family, a writing room, a recitation room, and a primary school room."

The following January, the Argus published a long story praising the new facilities--as well as the orderliness, efficiency, and spirit of the student body and faculty. The paper reported that the curriculum included:

"Four classes in Latin, two in Greek, two in French, two i%,German, two in Bourdon's Algebra, three in Elementary Algebra, one in Geometry, one in Natural Philosophy, tour in Arithmetic, one in Book Keeping, and three in English Grammar. . . . Instruction was also given regularly to both departments in Writing, Drawing and Vocal Music; and private lessons are given in Instrumental Music."

Noting that the number in attendance was 356, the report concluded:

"Our school is well organized, well disciplined, and well instructed; thus far it has more than answered our most sanguine expectations, and it now gives the most cheering promise or continued prosperity."

Though the U-M would not admit women until 1870, the Union School was coed from the start. The Argus noted in fall 1857 that residents paid nothing for the basic course of study, aside from a "modest fee" for those wishing to pursue foreign languages, art, or music.

"For the information or our friends residing in adjoining Towns, we give the terms—per quarter or 11 weeks—on which non-resident scholars are admitted: Higher Dept., English Studies, $4. Higher Dept., English and Languages, $5. Intermediate English, $3. Intermediate English and Languages, $4."

The high school was still educating many nonresidents when superintendent Perry wrote his history of the school district, circa 1880:

"It is one or the largest preparatory and academical schools in the country, and its reputation has become well nigh national. Or its 400 to 500 pupils, about 60 per cent are non-residents. Its annual tuition receipts go far toward cancelling the cost or its support, while many families become temporary residents or the city in order to secure the advantages of its superior instruction. Since 1861, the date or its rirst graduation class, the school has graduated 870 pupils, a large portion or whom entered the University of Michigan. It is doubtful if any other enterprise of the city has contributed more, even to its material prosperity, than has the Ann Arbor high school."

The initial curriculum was divided into two sections—classics and English. They covered similar material, but the former was more rigorous for college preparation. In 1872 a commercial course was started, and two years later, Horatio Chute was hired to teach science. He designed some of the first comprehensive courses in high school physics, astronomy, and chemistry, which were copied all over the country.

As enrollment grew, so did the building. A portico was added to the west side in 1857. In 1872 the school was extended on the east side by about forty feet, nearly doubling in size. That same year new heating equipment, seats, and bells were purchased. In 1889 a final expansion nearly doubled its size again, extending the school all the way to Huron Street.

The Gothic-style addition was no sooner completed than it was nearly destroyed: on September 10, 1889, smoke was seen pouring out of a window on the first floor. Fortunately, firemen and a group of about 100 boys were able to extinguish the fire in short order. Afterward there was discussion of taking steps to fireproof the building—but nothing was done.

Fifteen years later, on New Year's Eve 1904, the entire school was consumed by flames. Because water pressure was low and the fire was well advanced when it was discovered, the firemen could not save the building. Even though the blaze occurred in the middle of the night, most of the town came out to watch.

Principal Judson Pattengill, science teacher Horatio Chute, math teacher Levi Wines, and school superintendent Herbert Slauson organized a rescue mission. Aided by about 100 students, they were able to save much of Chute's prized physics laboratory equipment and most of the 8,000 library books. But much more was lost— textbooks, botany and chemistry equipment, school records, teaching aids, and sports equipment.

"Friends of mine who were high school students at the time tell me that they stood with tears running down their cheeks, crying unashamed as they saw the flames break out in one after another of their classrooms," local historian Lela Duff wrote in 1956. Overnight, the city had lost its showplace, the anchor of the development of a large section of the local real estate market, and a trendsetting educational institution.

Christmas vacation was extended just two days. With an outpouring of community support, classes resumed on January 12. The eighth grade moved en masse to Perry School, while high school classes met in borrowed churches and student religious centers, Moran's School of Shorthand, and the basement and storerooms of the new Hamilton Block at Thayer and North University.

Efforts to replace the school started the morning after the fire with an emergency meeting of the school board. A bond issue to fund a new building passed in March, 370-42. The district hired Malcomson and Higginbotham of Detroit to design both the new school and an adjoining library facing Huron (the district had already received a Carnegie grant for the library before the fire). Both are neoclassical designs with pillars, multisectioned windows, and arched main entrances. But the school is made of brick, while the library has a stone facade, and details differ subtly on the roofs and entrances.

The new school opened for classes on April 2, 1907, and was dedicated in a community ceremony ten days later. "That Ann Arbor now possesses the finest public school building in Michigan, if not in the United States, is admitted by all who have visited whether residents of the district or of other sections of the country," the Daily Times enthused.

If students entered at the side doors on Washington or Huron, which most did since they had their lockers there, they were on the bottom floor. About a third of that floor was the domain of Chute, who had been allowed to design it for science instruction. The gym was in the middle. At the back, on the Thayer Street side, were rooms equipped for vocational classes — wood and metal shops and drafting rooms.

Students who came in through the grand entrance on State Street could go down half a flight to the gym or half a flight up to reach the auditorium. The top floor had two big session rooms—combination study halls and places for students to be when not in class—facing State Street. Divided by sexes at the Union School, in the new school they were separated by alphabet. Longtime (1946-1968) principal Nick Schreiber was hired in 1936 to be the session teacher for L-Z. His counterpart, Sara Keen—called "Miss Kerosene" by the school wags—took care of the first part of the alphabet.

As in the Union School, the curriculum centered on subjects needed to get into college. But the new school also offered greatly expanded vocational courses—the state's 1905 compulsory school attendance law required the school to serve more students who weren't college-bound.

Many alumni remember the school assemblies. Veteran local radio personality Ted Heusel heard a broadcast of one of Hitler's speeches at an assembly in 1938. In another assembly he saw the chief archer from the movie Robin Hood stand in the balcony and hit targets on the stage. Another assembly featured U-M football star Tom Harmon. "He came down the aisles with everyone screaming," says Heusel.

Ted Palmer never forgot the assembly at which his history teacher played a trick on the students. "Miss Perry came from the right side and another Miss Perry came from the left and met in the center. It astounded everyone to see two Miss Perrys. It turned out she was an identical twin." Three years later, the sisters played a variation of the same trick on Dick DeLong and his classmates.

In the gym underneath the auditorium, students took physical education and played indoor competitive games. Palmer ran track by circling the gym, twenty-two laps per mile. "It wasn't much straightway, but some schools had less," he recalls. To practice the forty-yard dash, students ran the length of the hall that connected the Washington and Huron street entrances. This practice was halted when one student didn't stop in time and went right though the glass, seriously injuring himself.

For cross-country, Palmer jogged to West Park and ran there, returning to school for showers. Students participating in football or baseball ran to Wines (now Elbel) Field but were lucky in having a little building there where they could change and shower. Kip Taylor, who scored the first touchdown in Michigan Stadium, was one of their coaches. Beginning in 1938, Ann Arbor High's teams were nicknamed the Pioneers. A 1962 school booklet explains that the name was appropriate because the high school was "a pioneer in the true sense of the word, being one of the first schools in the state to have an organized athletic program."

At lunchtime students could eat at school, but "we liked to mingle with the college kids on State Street," recalls Palmer. The area was full of lunch places, well remembered by high school alumni — Kresge's counter for hot dogs, next door at Granada's for hot beef sandwiches, Betsy Ross in Nickels Arcade for deviled ham sandwiches, Toppers on Division for 150 hamburgers.

The lures of the neighborhood included the State Theater. In his memoirs, principal Nick Schreiber recalled a day, after a heavy snowstorm, when other schools closed but the high school remained open. In protest, a large number of students left for the matinee at the State. "When I learned of the exodus to the theater, I went over and asked the manager, a Rotarian friend, if I might have the theater lighted while I took the stage and announced that those students who did not return to classes were in for disciplinary action," Schreiber remembered. "They left the theater in haste."

The high school served well through the city's explosive growth in the 1920s, the Depression, and World War II. But after the war it was increasingly overcrowded. Built for 800 students, it was serving close to 1,400 by the time it closed in 1956. "The wood floors were creaky when we went there," recalls Bob Kuhn, a student in the 1940s. "The school seemed old. The cement stairs were worn."

The U-M, too, was growing rapidly and needed more space. So the city and university worked out a swap: the university got the high school, while the public schools got a large university-owned parcel diagonally across from Michigan Stadium—the site of the present Pioneer High. Included in the trade was Wines Field, now renamed Elbel, after Louis Elbel, author of "The Victors"; today, it is used for U-M band practice.

The university renamed the old high school the Frieze Building, after an esteemed nineteenth-century professor, and built an addition on the back. Even though people thought the building was run down during its last years as a high school, it lasted fifty years more with very little maintenance. But this year is likely to be its last.

In January the U-M regents voted to demolish the Frieze Building to make room for what they are provisionally calling "North Quad." Preservation activists and Ann Arbor High alumni argued for saving the building or at least the facade, but U-M planner Sue Gott rules that out, saying the university needs to use the entire site, including the State Street lawn. Still on the table is the possibility of preserving the Carnegie Library—if it can be combined successfully with the new building.

This article is based in part on Wil Cumming's history of the Ann Arbor Union High School. The complete text is aailable in the Ann Arbor Public Schools collection at the U-M Bentley Historical Library.

[Photo caption from original print edition]: When Ann Arbor High was dedicated in April 1907, the Daily Times declared it "the finest public building in Michigan, if not in the United States."

[Photo caption from original print edition]: After the fire on New Year's Eve, 1904. Overnight, the city lost its showplace, the anchor of the development of a large section of the local real estate market, and a trendsetting educational institution.

[Photo caption from original print edition]: The city and university worked out a swap, trading the old school for a large parcel diagonally across from Michigan Stadium—the site of the present Pioneer High

The Roy Hoyer Dance Studio

A taste of Broadway in Ann Arbor

Performers tap dancing on drums or flying out over the audience on swings, women in fancy gowns and plumes floating onto the stage to the strains of "A Pretty Girl Is Like a Melody." A Busby Berkeley musical on Broadway? No, it was right here in Ann Arbor at the Lydia Mendelssohn theater: "Juniors on Parade," a Ziegfeld-style production created by Broadway veteran Roy Hoyer to showcase the talents of his dance students and to raise money for worthy causes.

Hoyer came to Ann Arbor in 1930, at age forty-one. With his wrap-around camel hair coat, starched and pleated white duck trousers, open-necked shirts, and even a light touch of makeup, he cut a cosmopolitan figure in the Depression-era town. For almost twenty years, his Hoyer Studio initiated Ann Arbor students into the thrills of performance dancing as well as the more sedate steps and social graces of ballroom dancing.

Born in Altoona, Pennsylvania, Hoyer appeared in many hometown productions before a role as Aladdin in a musical called "Chin Chin" led him to a contract with New York's Ziegfeld organization. His fifteen-year Broadway career included leading roles in "Tip-Top," "Stepping Stones," "Criss Cross," "The Royal Family," and "Pleasure Bound." Movie musical star Jeanette MacDonald was discovered while playing opposite Hoyer in "Angela." But Hoyer himself by the end of the 1920's was getting too old to play juvenile leads. When the Depression devastated Broadway--in 1930, fifty fewer plays were produced than in 1929--Hoyer, like many other actor-dancers, was forced to seek his fortune elsewhere.

Hoyer came to Ann Arbor because he already had contacts here. In the 1920s he had choreographed the Michigan Union Opera, a very popular annual all-male show with script and score by students. His Roy Hoyer Studio taught every kind of dancing, even ballet (although the more advanced toe dancers usually transferred to Sylvia Hamer). On the strength of his stage career, he also taught acrobatics, body building, weight reducing classes, musical comedy, and acting.

His sales pitch played up his Broadway background: “There are many so-called dance instructors, but only a few who have even distinguished themselves in the art they profess to teach," he wrote in his program notes for "Juniors on Parade." "Mr. Hoyer's stage work and association with some of the most famous and highest paid artists in America reflects the type of training given in the Roy Hoyer School."

Pictures of Hoyer on the Broadway stage lined his waiting room, and former students remember that he casually dropped names like Fred and Adele, referring to the Astaire siblings. (Fred Astaire did know Hoyer, but evidently not well. When Hoyer dressed up his 1938 "Juniors on Parade" program with quotes from letters he'd received from friends and former students, the best he could come up with from Astaire was, "Nice to have heard from you.")

Hoyer's first Ann Arbor studio was in an abandoned fraternity house at 919 Oakland. He lived upstairs. Pat Bird Allen remembers taking lessons in the sparsely furnished first-floor living room. In 1933 the Hoyer Studio moved to 3 Nickels Arcade, above the then post office. Students would climb the stairs, turn right, and pass through a small reception area into a studio that ran all the way to Maynard. Joan Reilly Burke remembers that there were no chairs in the studio, making it hard for people taking social dancing not to participate. Across the hall was a practice room used for private lessons and smaller classes.

Back then, young people needed to know at least basic ballroom steps if they wanted to have any kind of social life. John McHale, who took lessons from Hoyer as a student at University High, says that for years afterward he could execute a fox trot or a waltz when the occasion demanded. Dick DeLong remembers that Hoyer kept up with the latest dances, for instance teaching the Lambeth Walk, an English import popular in the early years of World War II. (DeLong recalls Hoyer taking the boys aside and suggesting that they keep their left-hand thumbs against their palms when dancing so as not to leave sweaty hand prints on their partners' backs.)

Hoyer's assistants were Bill Collins and Betty Hewett, both excellent dancers. Burke remembers that when the two demonstrated social dancing, their students were "just enchanted." Several ballroom students remember the thrill of dancing with football star Tom Harmon. As a performer in the Union Opera, Harmon came up to the studio for help in learning his dance steps and while there obliged a few of the female ballroom students. "I'll never forget it," says Janet Schoendube.

While ballroom dancing was mostly for teens or preteens, tap and ballet students ranged from children who could barely walk to young adults in their twenties. (Helen Curtis Wolf remembers taking her younger brother Lauren to lessons when he was three or four.) Classes met all year round, but the high point of the year was the annual spring production, "Juniors on Parade."

The show was sponsored by the King's Daughters, a service group that paid the up-front costs and then used the profits for charity—medical causes in the early years and British war relief later. The three evening performances and one matinee were packed, and not just with the parents of the performers. During the drab Depression, people looked forward to Hoyer's extravaganzas all year long. Hoyer "jazzed us up when we needed it," recalls Angela Dobson Welch.

"Juniors on Parade" was a place to see and be seen. In 1933 the Ann Arbor News called it a "social event judging by the list of patrons and patronesses and the list of young actors and actresses whose parents are socially prominent." But the show's appeal wasn't limited to high society. Even in the midst of the Depression many less well-to-do families managed to save the money for lessons or worked out other arrangements in lieu of payment. Allen's mother helped make costumes; senior dance student Mary Meyers Schlecht helped teach ballroom dancing; Rosemary Malejan Pane, the acrobat who soloed in numbers that included cartwheels and splits, was recruited by Hoyer, who offered her free lessons when he learned she couldn't afford to pay.

The first act of the show featured younger children, wearing locally made costumes, while the second act showcased the more advanced students, who wore professional costumes. Every year Hoyer and Collins traveled to Chicago to select the dancers' outfits. For one 1935 number, the girls wore gowns that duplicated those worn by such famous stars as Ruby Keeler, Dolores Del Rio, and Carole Lombard. Live piano music was provided either by Georgia Bliss (on loan from Sylvia Hamer) or Paul Tompkins.

Sixty-some years later, students still remember such Hoyer-created numbers as "Winter Wonderland," a ballet featuring Hoyer and Betty Seitner, who stepped out of a snowball; "Floradora," six guys pushing baby buggies; "Sweethearts of Nations," eight girls in costumes from different countries, including red-haired Doris Schumacher Dixon as an Irish lass and Angela Dobson Welch as a Dutch girl. In "Toy Shop," dancers dressed like dolls; in another number, five girls, including Judy Gushing Newton and Nancy Hannah Cunningham, were done up in matching outfits and hairdos as the Dionne quintuplets.

"Juniors on Parade" ended with a high-kicking Rockettes-style chorus line of senior students. Then the stars returned home to their normal lives. Although some of them became very good dancers, none went on to careers in dance. (Doris Dixon later worked at Radio City Music Hall and was offered a job as a Rockette, but turned it down when she saw how hard it was.)

The last big show was in 1941. When the war started, Hoyer cut back on his studio schedule and went to work at Argus Camera, where they were running two shifts building military equipment. He worked in the lens centering area and is remembered by former Argus employee Jan Gala as "a lot of fun, full of jokes." Another employee, Catherine Starts, remembers that "he was so graceful. He took rags and danced around with them."

After the war Hoyer kept his studio open, but people who knew him remember he did very little teaching in those years. His health was failing, and his former cadre of students and stars had moved on to college and careers.

In 1949 ill health led him to move back to Altoona. He worked as assistant manager at a hotel there, then as a floor manager and cashier at a department store. He was still alive in 1965, when an Altoona newspaper reported that he was back home after a nine-month hospital stay.

Although it has been forty-five years since Hoyer left Ann Arbor, he is not forgotten. Hoyer Studio alumni say they still use their ballroom dancing on occasion, and even the tappers sometimes perform. Angela Welch remembers a party about ten years ago at which the Heath sisters, Harriet and Barbara, back in town for a visit, reprised their Hoyer tap dance number. And years after the studio closed, accompanist Paul Tompkins worked as a pianist at Weber's. Whenever he recognized a Hoyer alumna coming in, he started playing "A Pretty Girl Is Like a Melody."

Lane Hall

From the YMCA to women's studies

If the walls of Lane Hall could talk, they might recall discussions on ethical, religious, and international topics, and distinguished visitors such as Bertrand Russell, Reinhold Niebuhr, and the Dalai Lama. The elegantly understated Georgian Colonial Revival building on the south-west corner of State and Washington has been an intellectual center for student discussions since it was built. From 1917 to 1956 all varieties of religious topics were examined; from 1964 to 1997 it changed to an international focus. In October, after a major expansion and renovation, it was rededicated as the new home for women's studies at the U-M.

Lane Hall was built in 1916-1917 by the U-M YMCA. Within a few years it came under the control of the university's Student Christian Association, which included the campus branches of both the YMCA and the YWCA. In addition to organizing traditional religious activities, SCA published a student handbook, ran a rooming service, and helped students get jobs.

Funded in part by a $60,000 gift from John D. Rockefeller, Lane Hall was named after Victor H. Lane, a law professor and former judge who was active in SCA. When it opened in 1917, students could read books on religion in the library, listen to music in the music room, meet with student pastors in individual offices, or attend functions, either in the 450-seat auditorium upstairs or the social room in the basement.

SCA cooperated with area churches and also provided meeting places for groups that didn't have a home church, such as Chinese Christians and Baha'is. But Lane Hall is most remembered for its own nondenominational programs, which were open to all students on campus. Some, like Bible study, had an obvious religious connection, but the programs also included the Fresh Air Camp (which enlisted U-M students to serve as big brothers to neglected boys), extensive services for foreign students, and eating clubs.

Lane Hall became one of the most intellectually stimulating places on campus. "While the university was, much more than now, organized in tightly bounded disciplines and departments, our program was working with the connections between them, and particularly the ethical implications of those interconnections," recalls C. Grey Austin, who was assistant coordinator of religious affairs in the 1950s. "Religion was similarly organized in clearly defined institutions, and we were working, again, with that fascinating area in which they touch one another."

With the coming of the Great Depression, many students struggled financially. In 1932, looking for a way to save money, a local activist named Sher Quraishi (later an advocate for post-partition Pakistan) organized the Wolverine Eating Club in the basement of Lane Hall. The club's cook, Anna Panzner, recalled in a 1983 interview that they fed about 250 people three meals a day. She was assisted with the cooking by John Ragland, who later became the only black lawyer in town. About forty students helped with the prep and cleanup in exchange for free meals, while the rest paid $2.50 a week.

Lane Hall itself had trouble keeping going during the depression, often limping along without adequate staffing. Finally, in 1936, SCA gave Lane Hall to the university. The group didn't stipulate the use of the building but said they hoped it might "serve the purpose for which it was originally intended, that is, a center of religious study and activities for all students in the university." The university agreed and, while changing the name to Student Religious Association, kept and expanded the SCA programming.

The official head of Lane Hall would be a minister hired by the university, but the work was done by Edna Alber," recalls Jerry Rees, who worked there in the 1950s. "Alber ran Lane Hall like a drill sergeant," agrees Lew Towler, who was active in Lane Hall activities. "You'd try to stay on her good side."

The first university-hired director of Lane Hall was Kenneth Morgan. The high point of his tenure was a series of lectures on "The Existence and Nature of God" given by Bertrand Russell, Fulton Sheen, and Reinhold Niebuhr.

Morgan left during World War II and was replaced by Frank Littell. "He was a dynamic man who you either liked or didn't," recalls Jo Glass, who was active at Lane Hall after the war. "He made changes and left." After Littell, DeWitt C. Baldwin, who had been Lane Hall's assistant director, took over. Called "Uncle Cy" by many, he was an idealistic former missionary who also led the Lisle Fellowship, a summer program to encourage international understanding.

Although social action was important, religion as the study of the Bible was not ignored. For instance, Littell led a seminar for grad students on aspects of religion in the Old and New Testament. Participant Marilyn Mason, now a U-M music prof and the university organist, compares the seminar to a jam session, saying, "They were very open minded."

Other Lane Hall activities were just plain fun. Jerry Rees enjoyed folk dancing on Tuesday evenings in the basement social hall. Jo Glass has happy memories of the Friday afternoon teas held in the library. "You'd go to religious teas and meet people you met on Sunday, or go to international teas and meet people from other countries," she says, "but you'd go to Lane Hall and meet a mixture of everybody--all kinds of people wandered in."

Doris Reed Ramon was head of international activities at Lane Hall. She remembers that in addition to providing room for international students to meet, the building had a Muslim prayer room and space for Indian students to cook meals together. After World War II, with the campus full of returning servicemen struggling to make it on the GI Bill, a new eating co-op was organized, called the Barnaby Club. Member Russell Fuller, later pastor of Memorial Christian Church, recalls that the group hired a cook but did all the other work themselves, coming early to peel potatoes or set the table, or staying afterward to clean up.

The Lane Hall programming came to an end in 1956, when the religious office was moved to the Student Activities Building. The niche that Lane Hall held had gradually eroded as more churches established campus centers and the university founded an academic program in religious studies. Also, according to Grey Austin, there were more questions about the role of religion in a secular school. "The growing consensus was that the study of religions was okay but that experience with religion was better left to the religious organizations that ringed the campus."

In the 1960s, centers for area studies began moving into Lane Hall--Japanese studies, Chinese studies, Middle and North African studies, and South Asian and Southeast Asian studies, all of which were rising in importance during the Cold War. Many townsfolk, as well as students, remember attending stimulating brown-bag lunches on various international topics, as well as enjoying the Japanese pool garden in the lobby. During this time visitors ranged from president Gerald Ford and governor James Blanchard (who was delighted with the help the center gave him in developing trade with China) to foreign leaders such as the Dalai Lama and Bashir Gemayel, who became president of Lebanon, and famous writers such as Joseph Brodsky and Czeslaw Milosz.

One of the people who passed through Lane Hall during this period was Hugo Lane, great-grandson of Victor Lane. In response to an e-mail query, Lane recalled that he had an office in Lane Hall when he worked as a graduate assistant for the East European Survey, a project of the Center for Russian and East European Studies. "Needless to say, I took great pleasure in that coincidence. . . . On those occasions when my parents visited Ann Arbor, a stop at the hall was obligatory."

The centers for area studies eventually joined the U-M International Center in the new School of Social Work building across the Diag. After they left, Lane Hall became a temporary headquarters for the School of Natural Resources and Environment while its building was renovated. Then Lane Hall was vacated for its own extensive addition and renovation.

Today, the new and improved Lane Hall is home to the U-M's Women's Studies Program and the Institute for Research on Women and Gender. "It's wonderful space to the occupants, very affirming," says institute director Abby Stewart. "It feels good to be here."

The Detroit Observatory

It launched the U-M on the path to greatness

“How can we truly be called a nation, if we cannot possess within ourselves the sources of a literary, scientific, and artistic life?” asked Henry Philip Tappan, the first president of the University of Michigan, at his inaugural address in 1852. Henry N. Walker, a prominent Detroit lawyer in the audience, was inspired by Tappan’s vision and asked what he could do to help. Tappan suggested he raise money to build an astronomical observatory.

Born into a prominent New York family, Tappan had astonished his friends by agreeing, at age forty-seven, to head what was then an obscure frontier college. The attraction for Tappan, who previously had been a minister, professor, and writer, was the chance Michigan offered to put his educational philosophy into practice—“to change the wilderness into fruitful fields,” as he put it in his inaugural address.

An adherent of the Prussian model of education, Tappan believed that universities should expand their curriculum beyond the classics to teach science and encourage research. An observatory would embody the new approach perfectly—and Walker was ideally positioned to make it a reality.

Walker was a former state attorney general who often handled railroad cases. Well connected to both intellectuals and business people in Detroit, he attracted contributors who desired to advance scientific knowledge, as well as those who were interested in astronomy’s practical uses, particularly in establishing accurate time.

Because Walker raised most of its $22,000 cost from Detroiters, the building was named the “Detroit Observatory.” Tappan originally planned to have just one telescope, a refractor, suitable for research and instruction. But Walker offered to pay for a meridian-circle telescope as well. It would be better suited for measuring the transit of the stars and thus for establishing more accurate time—a matter of vital importance to railroads, which needed to run on schedule.

The regents sited the observatory on a four-acre lot, high on a hill outside the city limits. Although only half a mile east of Central Campus, it was then considered way out in the country. In the early days it could be reached only by a footpath, and astronomers complained of the long walk.

Tappan said later that he took credit for everything about the observatory except its location, which he would have preferred be on the main campus. “It has proved an inconvenient location, and has caused much fatigue to the astronomer,” he wrote. However, the remote site probably saved it: nearly every building of its age on Central Campus has long since been torn down.

In 1853, Tappan and Walker traveled to New York to order the refracting telescope from Henry Fitz, the country’s leading telescope maker. With an objective lens twelve and five-eighths inches across, it would be the largest refractor yet built in the United States, and the third largest telescope in the world, after instruments in Pulkovo, Russia, and at Harvard.

Meridian-circle telescopes were not manufactured in the United States, so Tappan went to Europe. On the advice of Johann Encke, director of the Prussian Royal Observatory in Berlin, he ordered a brass meridian-circle telescope from Pistor and Martins, a Berlin firm.

Tappan asked several American astronomers to head the new observatory, but they all turned him down. At that point he thought of Franz Brunnow, Encke’s assistant, who had been very enthusiastic about the project. Some objected to hiring a foreigner as astronomer, but Tappan prevailed. And certainly Brunnow was eminently qualified--he was the first Ph.D. on the U-M faculty. Under his direction, Ann Arbor soon became “the place to study astronomy,” according to Patricia Whitesell, the observatory director, curator, and author of A Creation of His Own: Tappan’s Detroit Observatory. Brunnow socialized with the Tappans and in 1857 married Tappan’s daughter Rebecca.

Tappan launched many other initiatives to turn the U-M into a first-rate university. He moved the students out of the two classroom buildings, letting them board in town, to make more space for academic uses--classrooms, natural history and art museums, and library. He encouraged the growth of the medical school, started the law school, and built the first chemistry laboratory in the country to be used exclusively for research and teaching. Under his leadership, the U-M granted its first bachelor of science degrees in 1855, its first graduate degrees in 1859, and its first civil engineering degrees in 1860.

But Tappan also made enemies--people who found his changes too precipitous or his manner too haughty. In 1863, Tappan was fired in a surprise vote by a lame-duck board of regents. Tappan moved his family to Europe, never to return; he died in Switzerland in 1881. Fortunately, his successors continued on the course he’d set, securing the U-M’s reputation as one of the nation’s leading universities.

Brunnow resigned after Tappan was fired; his star student, James Craig Watson, succeeded him. During Watson’s tenure, a director’s house was built west of the observatory.

In 1908 an addition was built to the east to hold a thirty-seven-inch reflector telescope. But as the campus grew out to the observatory, lights from the power plant (1914) and from the Ann Street hospital and Couzens Hall (both 1925) interfered with viewing. Over the decades that followed, the astronomy department transferred its serious research to a series of increasingly remote locations (currently Arizona and Chile). But the old observatory continued to be used for educational purposes until 1963, when the Dennison physics and astronomy building was completed.

In the tight-budget 1970s, there was talk of bulldozing the observatory. After World War II, the director’s house had been torn down to make room for an expansion of Couzens Hall, and the 1908 addition was razed in 1976, when the university decided it was too run down to maintain. But the original observatory was saved—though the rescue took a three-part campaign lasting close to thirty years.

Step one took place in the early 1970s, when a group of local preservationists led by John Hathaway, then chair of the Historic District Commission, and Dr. Hazel Losh, legendary U-M astronomy professor, convinced the university to give it a stay of execution.

Next, enter history professors Nick and Peg Steneck, who were called in by Al Hiltner, then chair of the astronomy department, and Orren Mohler, the former chair. Peg Steneck remembers that on her first tour of the building, “squatters were gaining access by climbing the chestnut tree out front and entering through the trapdoor in the roof. Evidence of occupancy, such as mattresses and Kentucky Fried Chicken boxes, littered the dome room, and a mural was painted around the wall of the dome.”

Nick Steneck tried to keep the building in use, setting up his office there, teaching classes, and using the upper level for the Collegiate Institute for Values in Science. Peg Steneck started research on the observatory’s history, which grew into a course she still teaches on the history of the university. Under the Stenecks’ prodding, the university took steps to stop the deterioration, fixing the roof, masonry foundation, and stucco.

Step three took place in 1994, when the university history and traditions committee asked vice president for research Homer Neal to restore the observatory. Neal assigned Whitesell, who was working in his office, to write a proposal, which she happily did, starting with Peg Steneck’s research.

Whitesell had a Ph.D. in higher education, was interested in both historic preservation and the history of science, and had long admired the observatory. Her new assignment, she says, “was a dream come true.” Neal agreed to the restoration and appointed Whitesell project manager.

Like the original construction, the million-dollar project, spearheaded enthusiastically by Anne and Jim Duderstadt, was paid for by gifts from private donors. The work began in June 1997 and was completed a year and a half later.

The university’s first total restoration project, the observatory has a lot of “first” and “only” distinctions. It is the oldest unaltered observatory in America that has its original instruments intact, in their original mounts, and operational. The meridian-circle telescope is the oldest in its original mount in the entire world. The building is the second oldest on campus (next to the president’s house) and the oldest unaltered one.

Restored, the observatory serves both as a museum of astronomical history and as a location for many academic events.

Ann Arbor's Carnegie Library

The steel magnate's gift was grafted onto the public high school Look closely at the north side of the U-M's Frieze Building on Huron opposite North Thayer, and you'll see that part of it is actually a distinct structure, set closer to Huron Street and built of stone blocks rather than brick. The main brick building was built in 1907 as Ann Arbor High School. The smaller stone one was built the same year, as one of America's 1,679 Carnegie libraries. Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) was a Scottish immigrant who made his fortune in steel (he replaced many wooden bridges with steel ones) and railroads (he introduced the first sleeping cars). After he sold Carnegie Steel to financier J. P. Morgan in 1901, he devoted his energies to giving away his vast fortune for social and educational advancement. Carnegie believed that great wealth was a public trust that should be shared. But he did not believe in straight alms-giving. (This was, after all, the Carnegie who broke the 1886 strike at his steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania, with 200 Pinkerton detectives. It took the state militia to put down the riots that resulted.) Building libraries to encourage self-improvement was consistent with Carnegie's philosophy of helping people help themselves. He paid for the buildings but required the community to provide the site and to pay for books and maintenance in perpetuity. At the time it was built, Ann Arbor's Carnegie Library was believed to be the only one in the country attached to another building. But it was a natural pairing in a town where the library and the high school had already been associated for nearly fifty years. The contents of the high school's library, which started operating in 1858, were the city's first publicly owned books. In 1883, the collection was given its own quarters on the second floor of the school, and Nellie Loving was hired to be the first librarian. At this time, or soon after, the general public also was allowed to use the library, thus setting the precedent, continued to this day, of the school board taking responsibility for the public library.

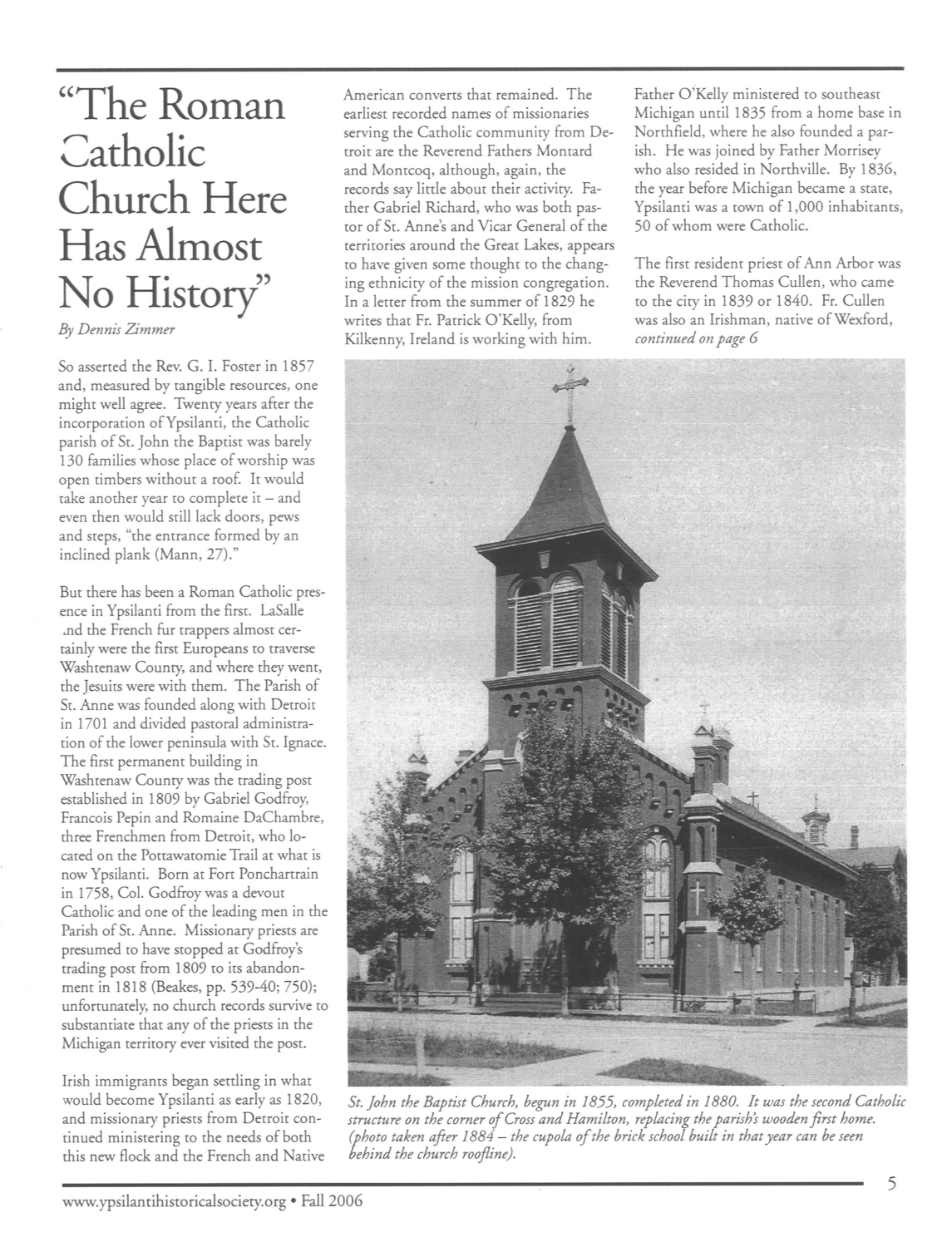

Another source of books for nineteenth-century readers was the Ladies Library Association. It was organized in 1866 by thirty-five women as a subscription library, based on a model started by Benjamin Franklin. By 1885, members had raised enough money — through Easter and Christmas fairs, lectures, cantatas, and strawberry festivals — to build their own library on Huron Street between Division and Fifth, in a building since torn down to make room for Michigan Bell. In 1902, Anna Botsford Bach, then president of the Ladies Library Association, suggested applying for a Carnegie grant to build a city library. The city's application was supported by the school board, the city council, and the Ladies Library Association. But after Carnegie granted $20,000 for the project in 1903, the applicants could not agree among themselves on a site. (The school board wanted the new library to be near the high school so the students could continue using it. The Ladies Library Association thought an entirely separate location would better serve the general public.) The deadlock was resolved only after the application was resubmitted in 1904 without the participation of the Ladies Library Association. This time, the city and school board were awarded $30,000. The Carnegie grant came just in time: on the night of December 31, 1904, the high school burned down. Luckily, school officials and students who rushed to the scene were able to save most of the library's 8,000 books before the building was destroyed. A few months later, voters approved a bond issue to build a new school. The school and the library went up simultaneously; both were designed by architects Malcomson and Higginbottom of Detroit, and built by M. Campbell of Findlay, Ohio. (The interior finishing work was done by the Lewis Company of Bay City, which later began building kit homes.) Despite its unusual connection to the high school, the library looked much like other Carnegie libraries: large pillars on the front, big windows, high ceilings, and a massive center staircase. The board of education, pleased with the result, called the new building "beautiful and commodious." In 1932, the high school library moved into separate quarters on the library's third floor, but students continued to use the lower floors after school. Gene Wilson, retired director of the public library, remembers that when he began working there in 1951, the busiest time of day was right after school, when the students would flock over to do their homework. By the time Wilson came to the library, the once spacious building was, in his words, "obscured by shelving on top of shelving. It was a rabbit warren of a building, typical of libraries at the end of their life, with six times as many books as planned for with stacks all over." Since the late 1940's, citizens' groups had been talking about the need for a new library. The school board took action in 1953, selling the high school and library building to the U-M for $1.4 million. (By then the new Ann Arbor High — now Pioneer — was under construction at the corner of West Stadium and South Main.) The board used the proceeds of the sale to buy the Beal property at the corner of Fifth and William as the site for a new library, ending nearly a century of close association between the high school and the public library. The library remained in the old Carnegie building for a few years after the high school moved out. It left in 1957, when the new public library on Fifth Avenue was ready for occupancy. The university remodeled and enlarged the old library and high school building and renamed it the Henry S. Frieze Building, after a professor of classics who also had served as acting president. In 2004 the university announced plans to build a dormitory on the site.