Rescued from the Scrap Heap

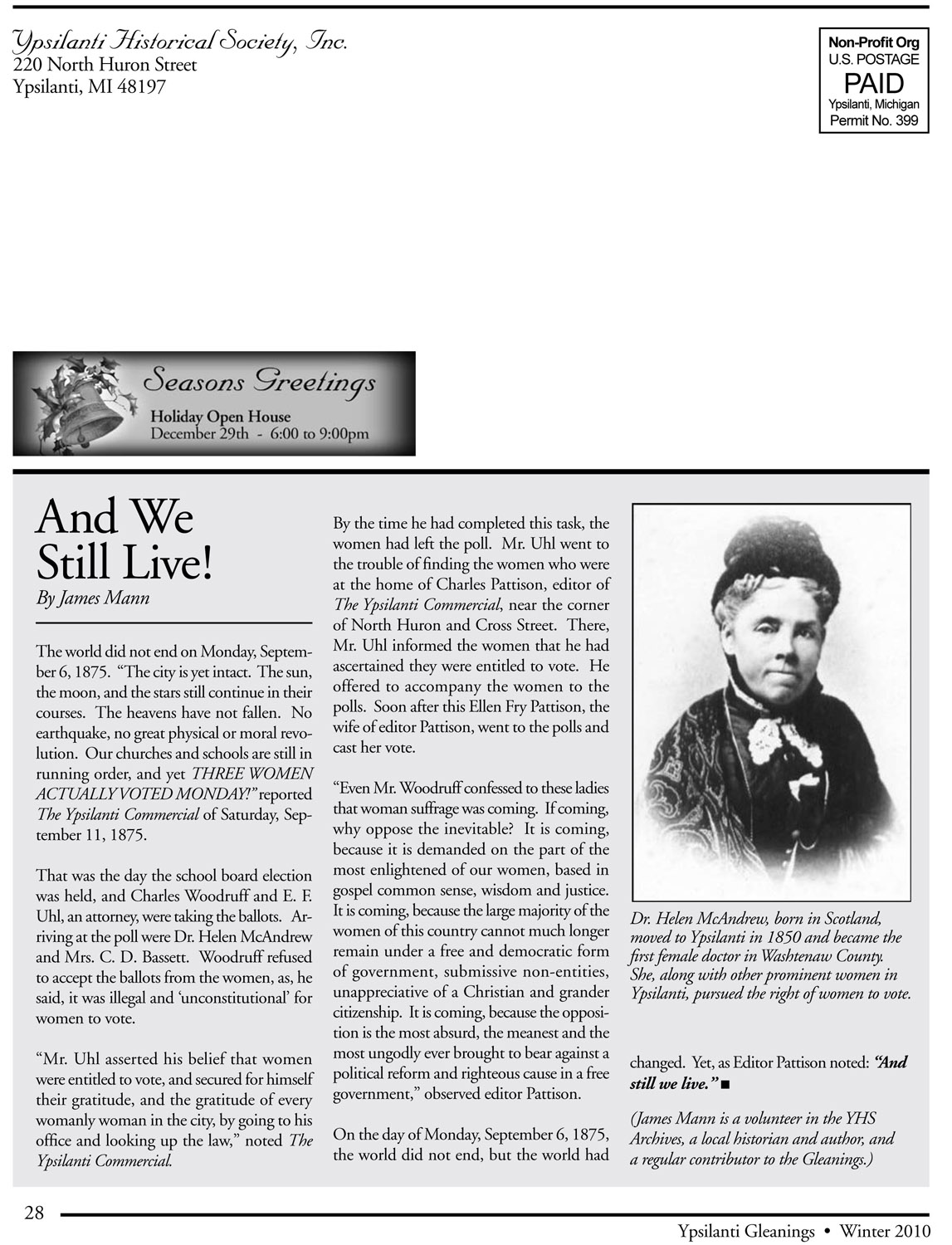

New owners are restoring the digs of Chelsea's most notorious figure—and villagers are pitching in.

For almost a century after Frank Glazier left Chelsea in 1910 to serve a term in Jackson State Prison, his huge house at 208 South Street went downhill. Despite Glazier's notoriety in local history, Chelsea residents did nothing to save it beyond occasional complaining.

Last January Todd and Janice Ortbring bought the twenty-one-room mansion, complete with tower, despite an eleven-page inspection report that mentioned termites, foundation cracks, and faulty wiring, among other problems. "We're probably crazy for doing it," says Todd Ortbring. "But we saw the opportunity to save a house that needed saving pretty darn quick." A lifelong resident of Chelsea, Ortbring appreciated Glazier's importance. His great-grandfather played in Glazier's band, and his grandfather owned the drugstore that Glazier had inherited from his father.

Glazier is without doubt the most important person in Chelsea's history after the founding Congdon brothers. In 1895 he started a company that manufactured cooking and heating stoves, and he was soon selling stoves worldwide. A civic leader, Glazier benefited Chelsea in countless ways—bringing electricity and water to town, providing jobs, and erecting landmark buildings that still define Chelsea, including the Clock Tower, the Welfare Building, the Methodist church, and a bank that is now 14A District Court. He was also a leader in state and local politics; in 1906 he was elected state treasurer and was being mentioned as a possible governor.

But at this peak of his prominence, his financial shenanigans were exposed: putting state money in his own bank, and taking out separate loans from banks all over the state using identical collateral from his stove company. Forced to resign as treasurer, Glazier spent two years in Jackson Prison before his sentence was reduce for good behavior. He spent the last ten years of his life at his cottage on Cavanaugh Lake.

Even today, reactions to Glazier are mixed. Some condemn him. Others excuse him by saying that what he did was common practice in those days and that he was being squeezed by the nationwide financial panic of 1907.

Glazier's house was divided into four apartments. For a long time it still looked beautiful from the outside; in the 1970s, however, an owner put up an ugly concrete-block addition for a fifth apartment, totally obscuring the elegant wraparound porch held up by fluted pillars.

The Ortbrings aim to make the house a single-family home again. Years of use as apartments obscured its original functions; it now appears that the house is actually two houses pushed together. The Ortbrings found a treasure trove of elements in a basement room—front porch columns, wooden doors with metal hardware, leaded glass windows, banisters, wooden benches, and two boxes of wooden pieces for the disassembled parquet floor—that are all elements of the puzzle.

Exactly when Glazier built his house is not clear. In 1895 a photo of it as a smaller house without a tower appeared in the Chelsea Headlight, a publication of the Michigan Central Railroad. Graffiti in the tower, written by Glazier's daughter Dorothy, are dated 1899. Ortbring believes the front was added to the back, but others say the back, the tower, and the front porch might have been the additions.

The Ortbrings have assembled a group of experts to help them, such as builder Bob Chizek and Chelsea architect Scott McElrath. Their strategy is to first replace the roof and paint the exterior. They plan to attack the inside apartment by apartment. The Ortbrings are living in the second-floor rear apartment and renting out three units while working on the apartment below them, which contains the original dining room. Taking off paneling and dropped ceilings, they found pocket doors, parquet floors, ceiling moldings, and a fireplace.

Restoring a house is almost like living with an original tenant. Todd Ortbring pictures the dining room as it was in Glazier's time. "Glazier was a man who liked to eat," he says. "The dining room would have been the most important room in the house, the site of many parties." Ortbring also imagines many meetings of civic and business leaders there. "They'd close the doors, smoke cigars, eat, and plot."

The Ortbrings hope to be done with their restoration by the time their sons, eight-year-old Blake and seven-year-old Grant, graduate from high school. They haven't ruled out someday turning it into a bed-and-breakfast or renting out a part of it.

Lots of Chelsea residents have offered to help in various ways, with information, labor, and even money. Recently the Ortbrings hosted a community open house. The huge turnout on a rainy day suggests that the people of Chelsea are prepared to forgive, or at least forget, Frank Glazier's misdeeds and celebrate all that he brought to the village.

—Grace Shackman

Photo Caption: Todd and Janice Ortbring, with builder Bob Chizek (right), are restoring the Glazier home, which has changed a lot since 1895.

Jeff Schaffer

Building Manchester

Jeff Schaffer was still in his twenties in 1976 when Manchester's village president, David Little, recruited him to join the village council.

"He knew a lot about construction," recalls Little. "He was a young guy, but so was I."

At the time, Manchester was building two bridges and overhauling its sewer and water systems. Schaffer worked at Wolverine Pipe Line, a company that pipes gas from Texas, and Little wanted the benefit of his experience.

At the next election. Little stepped down as village president. Schaffer succeeded him, staying two terms. During Schaffer's time in Manchester government, the village separated its storm and sanitary sewers, upgraded its sewage treatment plant, built a water tower, and added new fire hydrants.

Last March Schaffer was again elected village president, twenty years after his first stint. Today Manchester's main issue is growth—another good project for a man who takes pride, as Little puts it, in "physical acheivements."

Schaffer has lived in the Manchester area all his life, except for a brief stay in Ypsilanti while he attended Cleary College. His grandfather owned a dairy farm west of town at Austin and Sharon Hollow roads, and also co-owned a lumber yard where the Manchester Township Hall now stands. Schaffer says he grew up to value community service after seeing how his grandfather was always willing to help his neighbors.

"He'd say to someone who lost a barn and couldn't afford a new one, 'Don't worry, we'll give you the lumber,'" Schaffer recalls.

In the years between his two stints as village president, Schaffer served on Manchester's school board, and he and his wife, Connie, raised two children, Dawn and William. After twenty-seven years at Wolverine Pipe Line, he is now in charge of above-ground maintenance on Wolverine's systems from Kalamazoo to Detroit to Toledo.

Although Schaffer is a grandfather, he's still slender and still blond. He wears jeans, a T-shirt, and cowboy boots to work and treats colleagues and customers with small-town politeness—he addresses people as "ma'am" and "sir." His style, both as a boss and as a village leader, is to work as part of a team. "I encourage people on council to talk," he says.

In the last twenty years, Manchester has changed in many ways. There is no longer any active farming within the village limits. A few new industries have moved in. A village manager, Jeff Wallace, now runs day-to-day operations.

But Manchester is still a small town, and Schaffer says he appreciates the values that come with that—"the closeness, the willingness to be a good neighbor."

Still, he says, growth is a fact of life. Two housing projects are being built in the village, the homes and condos of Manchester Woods and the River Ridge apartments. Several other housing and light industry projects are in the discussion stage. "I'm not adverse to growth," explains Schaffer, "but we need to control growth, shape it so it's a good deal."

Appropriately, Schaffer uses a construction metaphor to describe his work as village president. "I keep laying the bricks in the foundation," he says. "It'll be here when we're long gone."

—Grace Shackman

Hubert Beach

Saline's eccentric ex-mayor

Hubert Beach, mayor of Saline from 1971 to 1974, lives in a house on McKay Street that has also been the home of three other mayors. But among all the mayors Saline has elected in its years as a city, Beach may well qualify as the most eccentric. For instance. Beach takes periodic trips to solar eclipse sites, from Acapulco to Nova Scotia, to "slay the cosmic dragon." He wears a mask, brandishes a sword, and beats a drum—his way, he says, of making sure the sun returns.

Beach also qualifies as the most hands-on mayor Saline has ever seen. While he was in office, the city and the state fought over whether to close Michigan Avenue, a U.S. highway, for the Memorial Day parade. Beach got in front of traffic and closed the street himself.

Beach was for years the city's one-man volunteer public works office. People remember Beach driving around town in "The Beast," an old school bus he converted into a mobile workshop. He was often pictured in the Saline Reporter scaling heights to do upper-story work, such as moving the bell from the old Methodist church to its new location and painting the flagpole in front of the post office. His motto: "If it's out of reach, call Beach."

"I've always loved climbing," he explains. "As a kid I climbed every tree I could, up to the tiniest branches."

He installed a sound system at the cemetery for the Memorial Day program, strung Christmas lights across the main intersection, and put in the finishing line banners for races. He designed and built a panel that lit up Yes or No to show how council members voted. When there was a blockage in the storm sewer, he looked down a manhole to see what was wrong, and discovered that a contractor had thrown old boards down the hole to get rid of them.

Mary Hess, who served her first term on city council when Beach was mayor, recalls that his expertise on TV systems, which he acquired from putting up antennas, came in handy when the city negotiated its first cable TV contract. And his knowledge of construction was very useful when the building code was amended.

Beach also worked as a tax preparer, and he used his accounting skills to develop clear budgets. "He wanted to make sure that the people we served understood where their money went," explains Hess. Bob Harrison, a friend of Beach's, remembers that Beach caught a major error while discussing adding sewage capacity with representatives of Ford Motor and a civil engineering firm. "Hubert's mind was sharper with numbers than if he was standing there with a calculator," says Harrison.

Growing up on a farm near Clinton, Beach learned to be practical and thrifty. He was born in 1923 and attended a one-room school. His dad died when he was nine, and he helped his mother run the farm. At age fifteen he started hauling milk from area farms. He moved to Saline in 1948, after marrying Catherine (Katie) Sliker.

Never one to sit still, he started his contracting business because he finished his milk route in midafternoon. He did almost anything—electrical work, carpentry, servicing fire extinguishers, installing security and sound systems. His specialty was height work: aerials, eaves troughs, flagpoles, lightning rods, church towers. To keep busy in the winter, he ran a tax business out of his house.

Beach first ran for public office because he was concerned about the fate of the dam at Wellers' that had washed out in the 1968 flood. The narrowing of the millpond had created a wetland, and there was talk of putting a trailer park there. After one term on city council, Beach ran for mayor. During his two terms, he saw the dam restored and the millpond dredged and restocked with fish.

Beach went through a period of political eclipse when he ran unsuccessfully for county commissioner twice in the 1970s and for mayor three times in the 1980s. In 1987, he won a seat on city council. He kept it until 1996; he resigned after an automobile accident and has still not totally recovered from his injuries.

Beach warned colleagues, "If you don't want the truth, don't ask me." His straightforward style and eccentric behavior earned him both admirers and enemies— which may explain why he lost elections despite his popularity.

"People either loved or hated him," says his daughter, April Pronk.

"Sometimes it's hard to change a first impression," explains Hess. "There was never any question where he was coming from. Compromise was not one of his strong points; he was firm in his convictions."

Beach describes his politics as populist, motivated by a concern for the underdog. "I always said garbagemen should make as much as administrators," he says. In his first race for county commission, he ran as a Democrat. In the next race, he ran as a Republican, since the Republicans are the dominant party in the Saline area. Although he counted both liberals and conservatives as political allies, he says he's a Democrat at heart "Republicans are too stuffy," he explains.

People appreciated Beach's accessibility. A regular for years among the friendly crowd at Benny's Bakery, Beach enjoyed debating and listening to others' opinions.

"He loved the city as no one I know," says Hess. Saline plans to honor him by naming a street in the new industrial park Beach Drive.

—Grace Shackman

The 1882 Firehouse

Ann Arbor's 19th-century showpiece recalls the time when fire was an ever-present peril

When Ann Arbor's 1882 firehouse opened, it was the most elegant and expensive building the city owned. That was fitting, because the greatest danger facing Ann Arbor in the nineteenth century was fire.

As late as the Civil War, Ann Arbor was still built almost entirely of wood--even the storefronts and sidewalks downtown. A spark was never far away because the city was lit by candles and oil lamps and heated by fireplaces and parlor stoves. Homes and businesses went up in flames so often that in 1865, a U-M student matter-of-factly referred to helping volunteers fight "the first fire of the winter."

Fires were also much more devastating then. In the early 1840's alone, fire destroyed Klinelob's distillery, S. Denton's ashery and soap factory, and the Michigan Central Railroad depot. The Michigan Central fire took out three neighboring properties as well, one of them a mill warehouse containing nearly 20,000 barrels of flour. Firemen couldn't even save their own buildings. In 1875, fire completely destroyed the Lower Town engine house, which had been erected just two years previously.

In Ann Arbor's first decade, the village's main fire-fighting strategy was simply to keep the town pump in good repair. That was vital because citizens responding to the call of "Fire!" needed plenty of water for bucket brigades. In 1836, responding to public pressure, the village council appointed fire wardens and other officers in each of the town's two wards, and men in both wards soon organized themselves into volunteer fire-fighting companies. The following year, the village bought its first fire engine, a hand pump on wheels that the firefighters dragged to the scene of a fire and filled by bucket brigades from the Huron River or nearby wells.

After the big fire at the Michigan Central station in 1845, the village bought its first hook and ladder wagon. It also started building cisterns at strategic locations around town to store rainwater for fire-fighters' pumps. In 1849, two new volunteer companies were organized: Eagle Fire Company No. One was a hose company with a hand-operated pump engine; Eagle Fire Company No. Two was composed of hook and ladder men. A year later, Ann Arbor levied a special tax to purchase ladders and new equipment for three more new companies: Deluge, Relief, and Huron.

Another new company was organized and named after their new pump engine, the Mayflower, just in time to fight a disastrous fire at the Clark School on Division Street in 1865. This fire led to a second cistern-building spree (a shortage of water was blamed for the severity of the damage to the school). Eventually there were cisterns at most major intersections, each about ten feet wide and fifteen to eighteen feet deep, protected with a manhole cover.

The volunteer companies were reorganized and renamed over the years, but there were usually four active at any one time, most divided internally into hose crews and hook and ladder teams. The different companies took turns being on call; for a big fire every firefighter in the city would respond.

After 1868 the firefighters were paid $5 a year (a ballot initiative to pay them $10 a year was defeated), but their real pay was the camaraderie they shared. Families felt connected to certain companies, and their sons would join when they came of age. (The tradition of fire-fighting families continues today: the son and grandson of Ben Zahn, fire chief from 1939 to 1955, joined the department, as did the son of Fred Schmid, fire chief from 1974 to 1985.) The companies met regularly for training and practice and to clean and repair their equipment. They sponsored balls and picnics, marched in parades, and toured fire departments in other cities to check out their methods--a practice so widespread that to this day, professionals on junkets are still sometimes referred to as "visiting firemen."

Having the proper fire-fighting equipment was a matter of civic pride. In 1870, when the city acquired a new hose, the whole town assembled to see which company could throw a stream of water the farthest. Using the cistern at the intersection of Main and Washington, the Protection company was able to shoot water 165 feet and 4 inches, beating the Relief company, who managed only 161 feet and 7 inches. In 1883, when the Vigilant hose boys got a new hose cart from Chicago, they showed it off by parading through town accompanied by a brass band.

Ann Arbor's volunteer firemen formed an enthusiastic lobbying group, most often convincing city council to make desired expenditures after major fires. The construction of the 1882 firehouse was their greatest success--and, it turned out, their last hurrah.

The new firehouse replaced an old one on the same site, a wooden structure not much bigger than a two-car garage, with a tower behind it to dry hoses. City council asked voters to approve an expenditure of $10,000 to build the new structure. It was an extraordinary amount at the time, and twice what was needed, according to an editorial in the Ann Arbor Courier. Nevertheless, voters approved it on the first ballot attempt. Choosing among four architects' submissions, council accepted a plan by William Scott of Detroit and hired local contractors Tessmer and Ross to build it.

The first floor of the new building was designed to store the hook and ladder and pumper wagons, while the second floor had a sizable hall for meetings and social events. The building was capped off with the bell tower, used to summon the volunteers (the number of rings indicated the ward the fire was in). Outside, a big cistern collected up to 300 barrels of rainwater. Architectural historian Kingsley Marzoff, in a 1970's article, described the building as a "modified Italian villa" and called it "a rare example ... of the nondo-mestic use of this type of design." He also compared the bell tower to those in Siena and Florence.

At the time the firehouse was built, there were 105 volunteer firemen (women wouldn't become firefighters until 1980) in four companies, which the 1881 county history lists as Vigilant, Protection, Defiance, and Huron. Each group had its own room in the firehouse, which it fitted up at its own expense. However, only Protection and Vigilant (which operated the town's only steam-powered pumper) kept their equipment there. Huron, which protected Lower Town (the part of Ann Arbor north of the Huron River), had a small station house north of the railroad tracks just off Broadway. Defiance's station was on East University, where the U-M's East Engineering building stands today.

The main fire hall's big upstairs room often served as a meeting place for other town functions. For instance, the Washtenaw Historical Society held their meetings there, and a very successful set of temperance meetings was held the year it was completed. The firemen celebrated the completion of the new hall with two major dances: a Thanksgiving dance, sponsored by the Vigilant Engine and Hose Company, and another on December 21--billed as "the dance of the season"--with the Chequamagon Orchestra, sponsored by Protection's hose company.

The volunteers didn't enjoy the use of the hall for long, however. The 1880's proved to be a pivotal decade for the city's fire-fighting efforts, and by its end, the citizen volunteers had been replaced by professional firefighters.

In 1885, the city's first piped water system was installed. It included 100 fire hydrants and largely solved the water shortage that had hindered fire-fighting efforts since the city's founding. Just three years later, Ann Arbor hired its first full-time firefighters. Responding to lobbying by volunteer fire chief Albert Sorg, city council hired Chris Matthews to live in the fire-house and William Carroll to be on duty nights. A year later, city council authorized a sixty-day trial period for a completely professional department, and Fred Sipley was hired as the first paid fire chief. The big upstairs room in the firehouse was divided into two dormitories and a recreation area. By 1893 the city had eight full-time firemen and five more on call.

Horses probably moved into the fire-house shortly after the firemen. Originally, the volunteers had pulled the equipment themselves, but as distances grew longer and the equipment heavier, horses became more desirable. They became an absolute necessity after the purchase in 1879 of the steam-powered pumper, which weighed so much it took more than a dozen men to pull it.

At first, horses were furnished by draymen, who would rush over when they heard the fire bell (the first to arrive got the job). For a short time the fire department paid the firehouse janitor, Jake Hauser, a biannual sum of $90 to use his horses whenever there was a fire. But when firemen threatened to quit if they didn't get their own horses, city council relented and purchased two in 1882, the same year work commenced on the new hall.

By 1888 the department owned five horses: three to pull the steam engine and two to pull the hook and ladder wagon. When the fire alarm rang, the horses knew exactly what to do. Released from their stable on the north side of the firehouse, they would stand in front of the wagon they were to pull and wait until their harnesses, which were held up by a system of pulleys and ropes, were lowered. On days when there were no fires, the horses had to be exercised, and there was a special cart for this, which was also used in parades.

The need to motorize the department was discussed in the early years of the twentieth century, especially after the devastating fires at the Argo Mill in 1903 and the high school in 1904. But the citizens were fond of the horses and resisted: as late as 1914, they voted against ballot issues to buy self-propelled fire engines. The voters finally relented in 1915, after a big fire at the Koch and Henne furniture store, but even then, the horses weren't replaced immediately. For a while the department used a combination of motorized and horse-drawn engines.

Barney, Duke, and Jim were the last three fire horses. Luckily for them, the chief at the time, Charlie Andrews, was an animal lover. According to his grandson, Bill Mundus, when the horses were no longer needed, Andrews sent them to the Heinzman farm west of town where they could enjoy their retirement years.

The stable behind the firehouse was converted to a workshop where firemen painted signs for the city between fires. Later it was converted to a garage, first used by the public works department to store their grader and dump truck and later by the fire department for the chief's car. Fred Schmid remembers moving the chief's car out onto the street so the firemen could play badminton there. The space is now part of the present fire station.

The fire department stayed in the 1882 building for ninety-six years. In 1978 they moved into the present main fire station, which had been built just north of the old building on Fifth Avenue.

"I didn't like the [old] building until I left," admits Schmid, the fire chief at the time of the move. "It was not easy to keep clean; there was a stoker boiler in the basement, high ceilings, the windows were rattlely, and the stairs were worn down." The old firehouse was also too small for modern equipment--one of the department's trucks didn't even fit and had to be housed at the substation at Stadium and Packard.

"Today, serious fires are few and far between," says fire battalion chief John Schnur. "We usually get them when they're small." In the past thirty years only a few fires have totally destroyed a building--Gallup Silkworth (a heating oil company) and the Old German restaurant in the 1970's, and the U-M economics building and the Whiffletree restaurant in the 1980's. So far in the 1990's, the most serious fires have been two abandoned fraternity houses.

"Houses just don't burn down anymore," says Schmid. He and Schnur list a number of reasons: earlier detection by smoke detectors and automatic alarms, faster response due to telephones and motorized vehicles (the average response time is now four minutes--less time than it previously took volunteers to reach the firehouse itself), sprinkler systems and unlimited water supply, and more fire-retardant building materials and techniques.

But with all these improvements, there are trade-offs. For instance, firefighters now wear more fireproof uniforms and use air tanks, but this means they can go deeper into a burning building and are closer to possible explosions. Also, according to Schnur, "Fires are smaller but more deadly." While in the nineteenth century most home furnishings were made of natural materials like wood or cotton, today there is a preponderance of synthetic materials, such as polyester and polyurethane, which give off gases when they melt. While the natural materials filled the firefighters' lungs with smoke, Schnur is worried that the chemicals they now breathe may be even more harmful to their future health.

With fires no longer the daily worry they were in the nineteenth century, fire marshall Scott Rayburn is concerned that the public has become too complacent. "It's a full-time job to keep the message out," he says. Today, with fewer fires to rush to, the 121-member fire department keeps busy being proactive: educating the public, performing fire inspections, and engaging in a constant schedule of training.

[Photo caption from original print edition]: Nineteenth century fires were frequent and devastating. This 1899 blaze on Main St. destroyed a branch of the Mack & Co. department store.

[Photo caption from original print edition]: A horse-drawn hook and ladder rig. The city bought its first horses around the time the 1882 firehouse was built.

The Three Courthouses of Washtenaw County

Conclusive proof that newer isn't always better

Just two weeks after he and Elisha Rumsey founded Ann Arbor in 1824, John Allen offered the state government free land for a courthouse. Though the site, at the corner of" "Huron" and "Main" on the partners' map, was uncleared wilderness, the state accepted, and designated Ann Arbor as the county seat. Allen had gambled (correctly, it turned out) that by giving up a small part of his 480-acre plot to get the county seat, he would be able to sell the remaining land for more. (The same ploy would later be used with similar success by the Ann Arbor Land Company to convince the University of Michigan to locate here.)

The courthouse was built a decade later by John Bryan, an early settler of Ypsilanti, at a cost of $5,350. It was a two-story building of brown-painted brick. On top was a cupola with a bell. The courtroom was upstairs, and the downstairs was rented to lawyers. Smaller one-story structures flanked the courthouse - one for the county clerk, the other for the register of deeds.

The courthouse square was surrounded by a white picket fence with a gate and turnstyle at each corner. There was a hitching rail on the corner of Huron and Fourth where people left their horses while they did business inside.

From the beginning, the courthouse and its surrounding square were the center of Ann Arbor's community life. Public events were held in the upstairs courtroom, and the grounds were used for larger gatherings. In 1860, summoned by the courthouse bell, citizens heard a city official standing on the courthouse steps read a telegram announcing that Fort Sumter had been fired on.

By the end of the Civil War it was obvious that Washtenaw County had outgrown its courthouse. Voters turned down the first request to fund a new one, in 1866. Put to the voters a second time in 1877, a funding measure passed, thanks partly to a fire in the sheriff's office that scared people: a similar fire in the courthouse, they realized, could have wiped out all the county's legal records.

The new courthouse, designed by G. W. Bunting, cost $88,000, and was far more ostentatious than the modest structure of 1834. Perched in the middle of the square, surrounded by a grassy lawn full of shade trees, the red brick building trimmed with limestone stood three stories high and was topped with a seven-story clock tower. There were smaller towers at each corner and a statue of Justice above each of the four entrances.

The inside of the courthouse was as splendid as the outside. According to Milo Ryan's autobiography View of a Universe, "all of the four doors entered into the same central lobby. From there grand staircases ascended between carved railings, of some dark wood deep-hued with stain and, probably, dust. On the main floor very tall doors opened into vast high-ceilinged offices, their walls lined with shelves of large books."

The new courthouse, like the original, was a center of community events. Memorial Day parades started there. Fourth of July programs were held on the grounds, and summer band concerts. Visiting celebrities, including William Jennings Bryan, spoke from the courthouse steps. When no events were scheduled, workers ate lunch there, children played around the war memorial on the lawn, and others exchanged gossip on warm summer evenings.

The second courthouse served the county for over seventy years. But like the first, it eventually became too small as Washtenaw County continued to grow. Micki Crawford, recently retired as chief deputy county clerk, remembers that when she began work for the county in 1950, the nineteenth-century courthouse was crowded, unsafe, and inefficient. "It may have been beautiful, but it was no joy to work in," she recalls. Clerk's forms were stored in the hallway. Records were kept under the stairs. Rats and mice were a problem. And most seriously, it was no longer felt to be safe from fire. The seven-story clock tower had been removed in 1948 because there were fears it might topple. The Main Street entrance was closed because the steps were in such bad shape.

County residents and officials offered various solutions. One was to build the new courthouse on the site of the County Infirmary (now County Farm Park), or at Vets Park. Most residents, though, wanted the courthouse to stay in the center of town, near the title companies and law offices. What really cinched the decision to put the new courthouse on the same downtown site was the discovery that under the terms of the original grant, if the courthouse land was sold for another use, the proceeds would go to John Allen's heirs, not to the county.

In the whole debate, no one seems to have mentioned the possibility of keeping the 1877 courthouse and renovating it. But in the age before preservation became a common cause, replacement seemed the only option. Mayor William Brown, speaking in favor of a new courthouse, demonstrated the assumptions of the era perfectly: "The present courthouse was built before the turn of the century. Need I say more?"

Again, it took two elections for the voters to approve the necessary funds. Voted down in 1950, the new courthouse was approved in 1955. The final plan, designed by architect Ralph Gerganoff of Ypsilanti, cleverly addressed the problems of parking and having to move twice, which had worried proponents of the other sites. The new courthouse would be built around three sides of the existing one, which would continue functioning until the new one was finished. Then the old would be torn down and that space used for parking.

The project worked as envisioned. Helen Rice, who was working at the courthouse at the time, remembers, "I could open my window and reach out about twelve inches and touch the new building." Much of the move was effected by employees handing materials out the old windows into the new.

Today, many lament the passing of the old courthouse, both for its architecture and for the sense of community fostered by the green around it. When the Downtown Landmarks Commission finished their work in 1988, they unanimously agreed to use Milt Kemnitz's portrait of the 1877 courthouse on the cover of their report. Commission chair Susan Wineberg explains, "It's the one that got away."

[Photo caption from original print edition]: The courthouses of 1834 (above) and 1877 (left). To avoid moving twice, the current courthouse (bottom) was built on the old one's lawn in the 1950's.

Ann Arbor's Permanent Polling Places

Dotted around the city, they were the headquarters of seven self-reliant wards.

These days, Ann Arbor's five political wards are transitory entities. Wards are redrawn every ten years to insure that they represent as equal populations as possible, and boundaries are freely adjusted by the party in power to create the maximum number of winnable seats.

That wasn't the case before the current city charter was adopted in 1956. Ann Arbor's old ward boundaries lasted much longer--some for more than 100 years--and the wards formed cities-within-the-city that provided residents with an identity more significant than a mere voting address. By 1896 there were seven wards, each with its own school, its own constables and fire wardens, and even its own permanent headquarters: a city-owned polling place.

Four of those polling places were in buildings expressly built for the purpose: 310 S. Ashley, 926 Mary Street, 420 Miller, and 411 S. Forest (now 411 Washtenaw). Another, at 1006 Swift, was a remodeled house. The other two wards had permanent homes in larger buildings: the old City Hall and the Armory. All but the old City Hall still stand, but only the Mary Street structure will actually be used as a polling place in the April 3 election.

Ann Arbor's four original wards were established when the city was incorporated in 1851. They were divided east and west by Huron Street, and north and south by S. Main and N. Fourth. The First Ward consisted of the southeast quadrant--basically the downtown. The Second Ward, today the Old West Side, went southwest. Northwest was the Third Ward, the area between downtown and Mack School. Northeast was the area known today as "the Old Fourth Ward."

The remaining wards were added gradually over the next fifty years: the Fifth Ward in 1861, when Lower Town, the settlement across the Broadway bridge, decided to join the city, and the Sixth (1868) and Seventh (1896) in response to growth in the university area.

In the nineteenth century, a ward's entire population voted in one place, usually either a public building or a store. The move to acquire permanent ward polling places began in 1895, when City Council appointed a committee "to investigate the matter of a location for ward buildings in the First and Second Wards." The committee reported back that there were "certain desirable pieces of property that can be obtained at reasonable prices, which if they are not now secured may soon pass into other uses and out of the reach of the city entirely." Acting on the committee's recommendation, the council purchased two pieces of land: the southwest corner of Huron and Fifth Avenue in the First Ward and 310 S. Ashley in the Second.

The Second Ward polling place was the first built, in 1901, using bricks from a university building torn down the previous year. Next came the Seventh Ward building, completed in 1905 on Mary Street. The First Ward followed with its own polling place in 1908, but not in the freestanding building originally planned. By buying property adjacent to its first lot, City Council eked out enough land to build a complete City Hall. The First Ward polling place was relegated to the basement.

The Third Ward building was erected in 1911 on the northeast corner of Miller and Spring. The same year, Fourth Warders were given a room in the new Armory on Ann Street at Fifth Avenue, and the city remodeled an existing house on Swift Street for the Fifth Ward. Finally, in 1930, the Sixth Ward got its own polling place when the city built an attractive Tudor-style brick building at 411 S. Forest.

Although the ward buildings were set up primarily for voting, groups often requested permission to use them for social gatherings. Petitioners included the Third Ward Men's Club, the Boy Scouts, a Sunday school, and the Players Club. Several times, stores asked permission to use the polling places for temporary storage. In World War II, the Second Ward polling place on S. Ashley was used by the draft board and as a civil defense headquarters.

Paper ballots were used in city elections until 1941. That year, City Council, acting on the recommendation of a special committee, decided to purchase twenty-three nine-party, forty-column, manually operated voting machines. (Some of them are still in use.) A few months later, council appointed deputy treasurer Fred Looker as "custodian of voting machines." Mickie Crawford, deputy county clerk, remembers Looker telling her that in the early days of the new system, people were very distrustful of the machines and frequently asked for recounts on the suspicion that the machines had messed up.

In 1944, the man who eventually replaced Looker, Sam Schlecht, worked on his first election. Looker asked Schlecht, who worked in the Water Department, to help at the Miller Avenue polling place. "In those days, everyone voted," Schlecht says. He recalls that candidates' supporters brought in carloads of people to vote. Many voters were illiterate, and Schlecht spent the day showing them, at their request, where President Franklin D. Roosevelt's name was on the ballot.

Later, as custodian of the machines, Schlecht would start preparations several days before an election. He had to take wood, coal, or kerosene to each of the polling places to start up the potbellied stoves, not only for the comfort of the poll workers, but to warm up the machines enough to be used. He also brought in all the supplies needed, including paper, sharpened pencils, signs, ropes to show the voters how to line up, and the huge old poll books that listed every voter in the ward. The books were so heavy, Schlecht says, that it took two men to lift them.

The use of the ward polling buildings was phased out in the 1950s and 1960s as the city's population growth and the consequent division of wards into precincts created the need for more and larger voting places. Schlecht doesn't remember a specific decision, but one by one, except for Mary Street, the polling places stopped being used. Today, there are sixty-three voting precincts, the majority of them in schools.

The Second Ward building was the first to leave city hands, in 1959. Today it's owned by John and Mary Hathaway, who use it as a meeting place. The old City Hall was replaced by the City Center Building, but all the other ward polling places survive. The Third Ward building, expanded and remodeled, is now Knight's Market. The Fourth Ward polling room has been reclaimed by the Armory. The Fifth Ward polling place on Swift has reverted to a private home, and the Sixth Ward building on Washtenaw has also been converted into housing.

[Photo caption from original print edition]: The polling place at 926 Mary (above) is the only one of seven built between 1901 and 1930 that's still used in elections. 1006 Swift (top left)--originally a private home--has reverted to residential use. The brick First Ward building at 310 S. Ashley is now owned by John and Mary Hathaway, who use it as a meeting place.