Affordable Care

Last February the doctors at Packard Health began seeing some strange illnesses.

The coughs, troubled breathing, sweats, and fevers didn't test as any kind of influenza that they knew. Nevertheless, they were in a "state of shock and awe," says executive director Ray Rion, when in March the first confirmed Covid-19 cases were reported in Michigan.

Polio in Ann Arbor

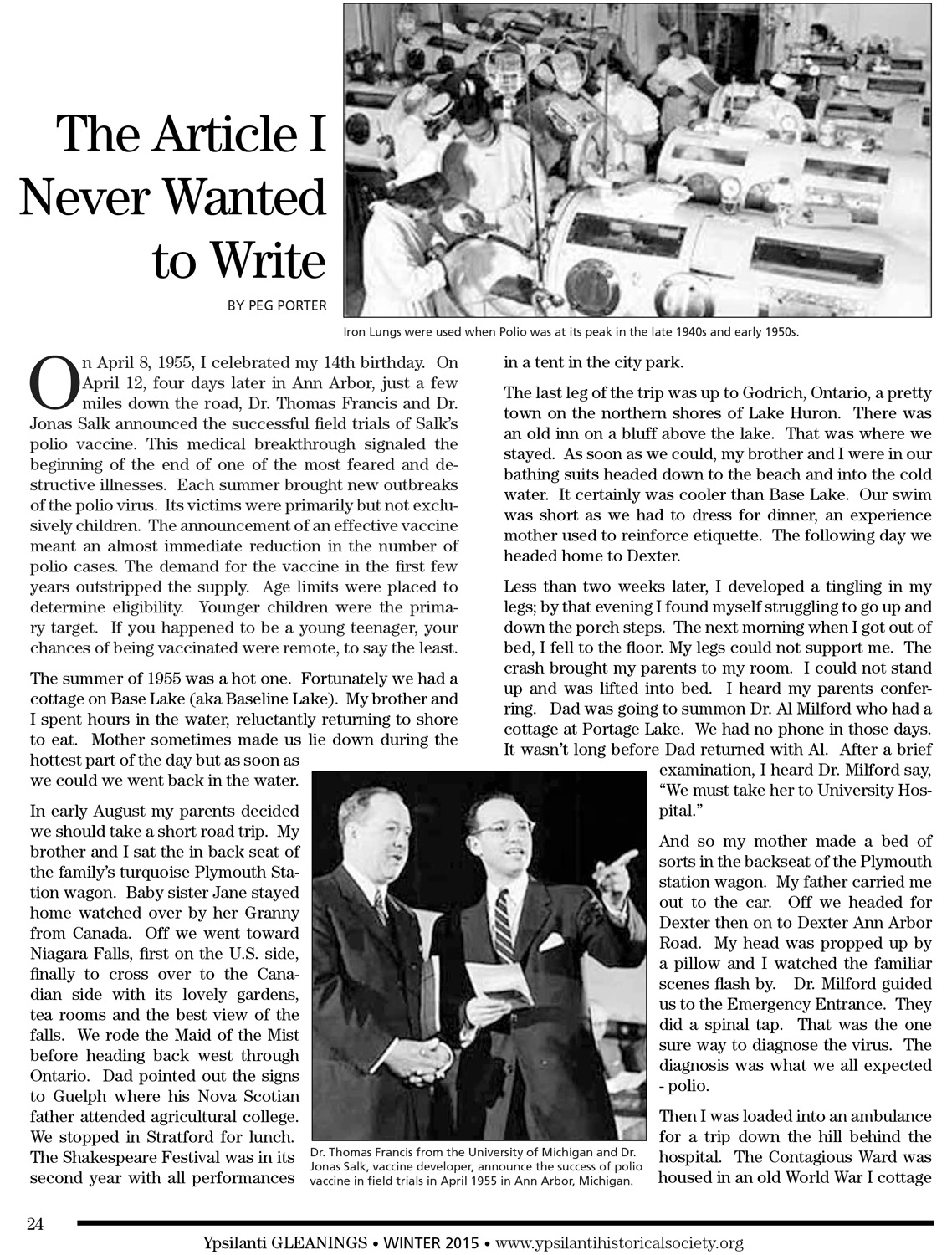

People were so desperate to save their children from the dreaded disease of polio, that when the first vaccines were sent to Ann Arbor in 1955, they were stored at the police department in a refrigerator, locked with a chain around it. Just three weeks previously, on April 12, Dr. Thomas Francis of the U-M’s School of Public Health had made the momentous announcement that the vaccine developed by Dr. Jonas Salk, which used killed polio viruses to give immunity, was “safe, effective and potent.”

People were so desperate to save their children from the dreaded disease of polio, that when the first vaccines were sent to Ann Arbor in 1955, they were stored at the police department in a refrigerator, locked with a chain around it. Just three weeks previously, on April 12, Dr. Thomas Francis of the U-M’s School of Public Health had made the momentous announcement that the vaccine developed by Dr. Jonas Salk, which used killed polio viruses to give immunity, was “safe, effective and potent.”

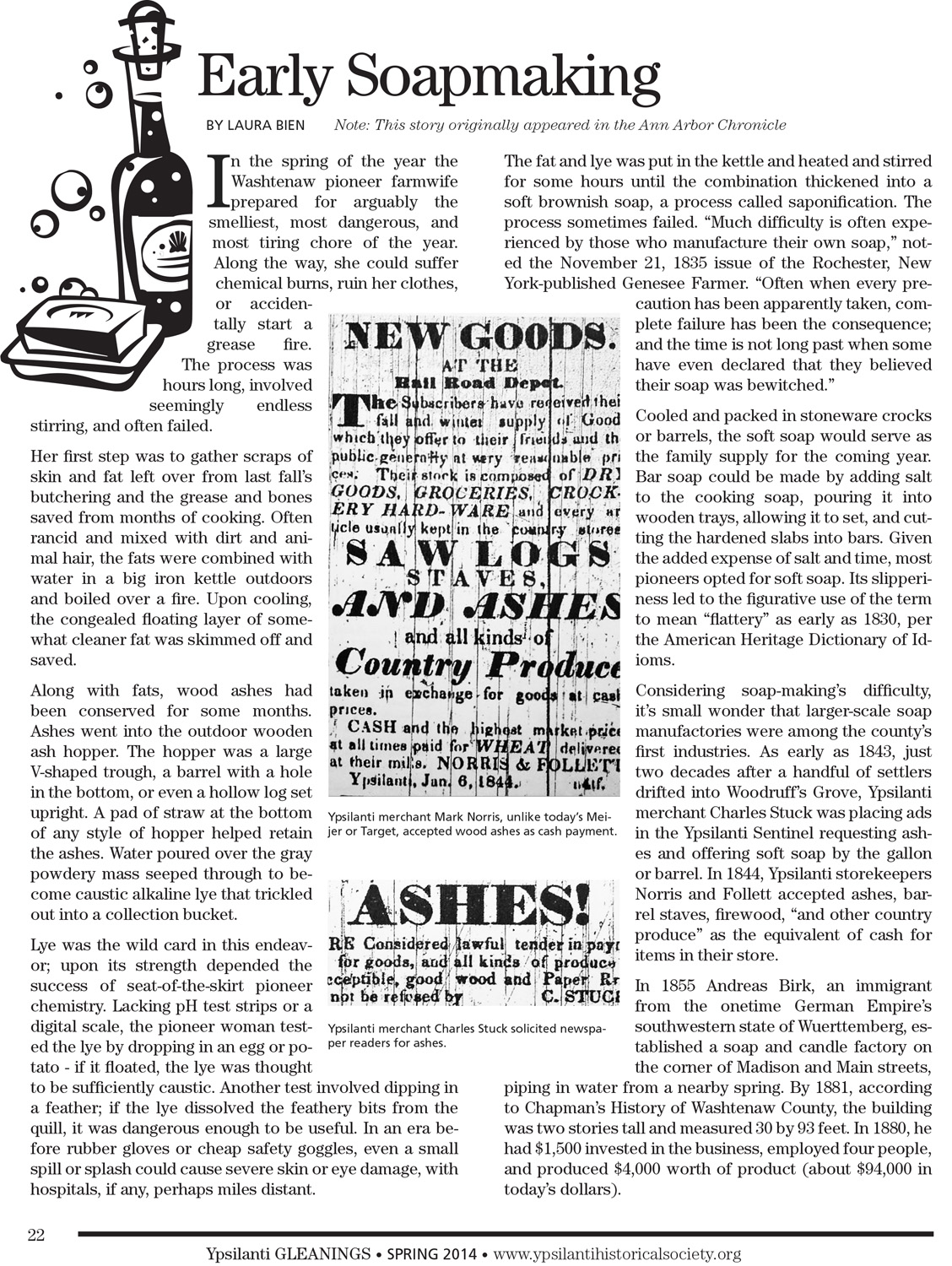

“Vaccine will end polio as a major health threat,” was the headline in the April 12, 1955 Ann Arbor News, shortly after Francis gave his report at Rackham Auditorium. The announcement was made in Ann Arbor because of the key role the University of Michigan had played in the vaccine’s development. Francis, who had earlier developed a flu vaccine, joined U-M’s Public Health Department in 1941, followed the next year by Salk, who Francis had mentored at New York University. Salk left in 1947 for a job at the University of Pittsburgh, where he developed the polio vaccine using tools he had learned from Francis.

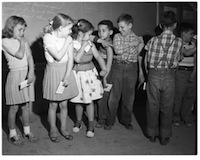

Francis was hired by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (often called the March of Dimes after its major fundraiser) to conduct tests to determine if Salk’s vaccine worked and was safe. Using blind studies so that none of the almost two million children who were tested knew whether they were receiving the vaccine or a placebo, he found that it met both criteria. The children who had received the placebo were at the head of the line to get the real vaccine.

Francis was hired by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (often called the March of Dimes after its major fundraiser) to conduct tests to determine if Salk’s vaccine worked and was safe. Using blind studies so that none of the almost two million children who were tested knew whether they were receiving the vaccine or a placebo, he found that it met both criteria. The children who had received the placebo were at the head of the line to get the real vaccine.

On April 11, the day before Francis presented his report, officials from the polio foundation and the scientific world began arriving by train. They were welcomed with much fanfare at the New York Central Station (now the Gandy Dancer). The most important arrival was Salk, who came with his wife and three boys. The two oldest had been born in the old maternity wing of University Hospital, which by an interesting coincidence had been turned into Francis’s evaluation office where he and his assistants did the monumental job of collating the data, which in the days before computers was very labor intensive. Pictures show rows of file cabinets, a card catalog, and piles and piles of papers.

Francis had refused to give any prior information on his findings, not even a hint if they were positive or negative, saying he wanted to make absolutely sure that everything was accounted for. He presented his report at a closed meeting by invitation only. As well as scientists, the audience included 400 reporters. When Francis finished, copies of his report were wheeled in on a cart. The reporters started grabbing them and running to telephones to phone their respective newspapers, magazines, radio and TV networks. A room had been set aside for the reporters with four teletype machines and ten tables with seating for six people sharing three phones. The Ann Arbor News let the AP use their darkroom to send pictures to their wire services.

Three weeks after Francis announced his findings, local children began getting the vaccine. On April 29, 1955, one hundred volunteer doctors began vaccinating first and second graders at thirty area schools. The newspaper was filled with pictures of brave children getting their shots. The 7000 doses were provided by the polio foundation. They arrived at the county health department a few days earlier and were stored at the police department.

The county health department found the money to buy enough vaccine to inoculate the more than a thousand children receiving welfare support, again using volunteer doctors. The rest of population went through their private doctors. The physicians were so overwhelmed with calls that a post card system was set up for parents to send in and even these got so out of hand that the doctors asked that parents only request shots for children at least one year old and not yet in first grade. The decision to start with the younger children was no doubt made because that was the age group most likely to die of the disease. Parental permission forms were needed but hardly any parents refused. In the first batch, out of 804, only ten said no.

Ann Arbor, like the rest of the nation, had been grappling with polio for years before the vaccine. The first mention in the Ann Arbor News was in 1934 when a National Committee of Birthday Balls was organized across the nation on FDR’s birthday, with money earmarked for polio research. The local ball committee included Ann Arbor’s mayor Robert Campbell and the editor of the Ann Arbor News Arthur Stace. In the following years the Ann Arbor News was filled with human interest articles about victims coping with the dreaded disease- a women spending half the day in therapy and the other half learning accounting, a girl playing the piano, a boy able to ride a bike while wearing braces. The public library loaned out a device so sufferers in the hospital who couldn’t raise their head could read on the ceiling.

There was also much fundraising - kids having backyard carnivals or circuses, a bake sale at the hospital, newspaper drives, service clubs like the Eagles taking on projects. The metal workers and the electrical unions made replicas of iron lungs that could be used as canisters to put money in. The March of Dimes was a yearly event when mothers went door to door collecting money, often in dimes. (FDR’s picture is on the dime for this reason.) These articles continued after the announcement of the vaccine, but began to taper off as more people were protected.

Francis died in 1969. Salk, who died in 1995, returned to Ann Arbor twice. In 1977 he was the featured speaker at that year’s U-M Medical School graduation. In 1995, he made another visit, this one on April 12, exactly 40 years after the announcement that his vaccination was effective and safe and at the same place, Rackham Auditorium, to be honored by the March of Dimes. At that time he said his work was focused on finding a vaccine against HIV.

See all Oldnews articles and photos on the history of polio and the polio vaccine in Ann Arbor.

122 West Main Street

From healing souls to healing bodies

When Manchester physician Evelyn Eccles and her husband Tom Ellis bought the former Methodist church on Main Street in 1985, the building hadn't been used for thirteen years. Everything was still in place—the pews, the stained glass windows, and even the organ, still in working order, with bellows in the basement.

"It looked like they finished a service, then locked the door and left," recalls Eccles.

Today the building, built in 1837 and 1838, houses Eccles's family medical practice. She's kept the original stained glass, high ceilings, lights, and wainscoting. Some of the old pews are used as waiting benches. Eccles achieved this miracle of reuse by creating what she calls "a building within a building" All the offices were built away from the outside walls, so that the light from the stained glass pours in unimpeded.

"It's an old-time frame with joists into beams," explains Bob Lowery, who built an addition to the church in 1958. "It's made with oak timber, probably cut at the local sawmill." Emanuel Case's sawmill on the River Raisin, built in 1832, helped draw settlers to what is today the village of Manchester.

The church was originally built by the Presbyterians; Manchester's original settlers were of British descent, and the Presbyterian Church was the first religious group to organize in the village. Seventeen people attended the congregation's first meeting in December 1835 at the home of Dr. William Root. They began work or the church two years later.

The church played an important part in village life in the nineteenth century. A school occupied the building's basement, and the congregation sponsored speakers, such as a controversial antislavery lecturer. But membership dwindled as more churches were organized—Lutheran, Baptist, Universalist, and Roman Catholic. In 1893 the Presbyterians disbanded and sold the building to the Methodists, who had founded their local congregation in 1839. The few remaining members placed a memorial window in the front of the church. (It is still there, partially hidden by a display of medical pamphlets.)

The building served the Methodists well in the first half of the twentieth century. In 1904 they built a parsonage next door, and in 1928 they installed the organ and remodeled the rostrum, pulpit, and communion rail. But after wona War II, the congregation outgrew the building. In 1958 the Methodists built a two-story addition that linked the church and parsonage, and in 1965 they converted the parsonage into Sunday school rooms, moving the pastor to a new parsonage on Ann Arbor Hill. Still, soon after, the congregation decided they needed a new church.

"There was no parking," explains Lowery, especially on Sunday, when the Methodists had to compete with the congregations of nearby St. Mary's Catholic Church and Emanuel United Church of Christ. "The church needed work. It was cheaper to build a new one." Ground was broken on M-52 in 1971, and the first service was held there in 1972.

While the old church stood empty, the new addition was converted to offices and the old parsonage into apartments. Dr. Howard Parr bought the old organ but left it in the church until Eccles and Ellis bought the building. Before moving the organ (which is still in storage awaiting an interested buyer). Parr organized a meeting of the Manchester Area Historical Society in the old church so that people could get a last chance to hear it. Parr himself played hymns, and Historical Society members sang along.

—Grace Shackman