The Saline railroad depot

A hiking trail turns old tracks to good use

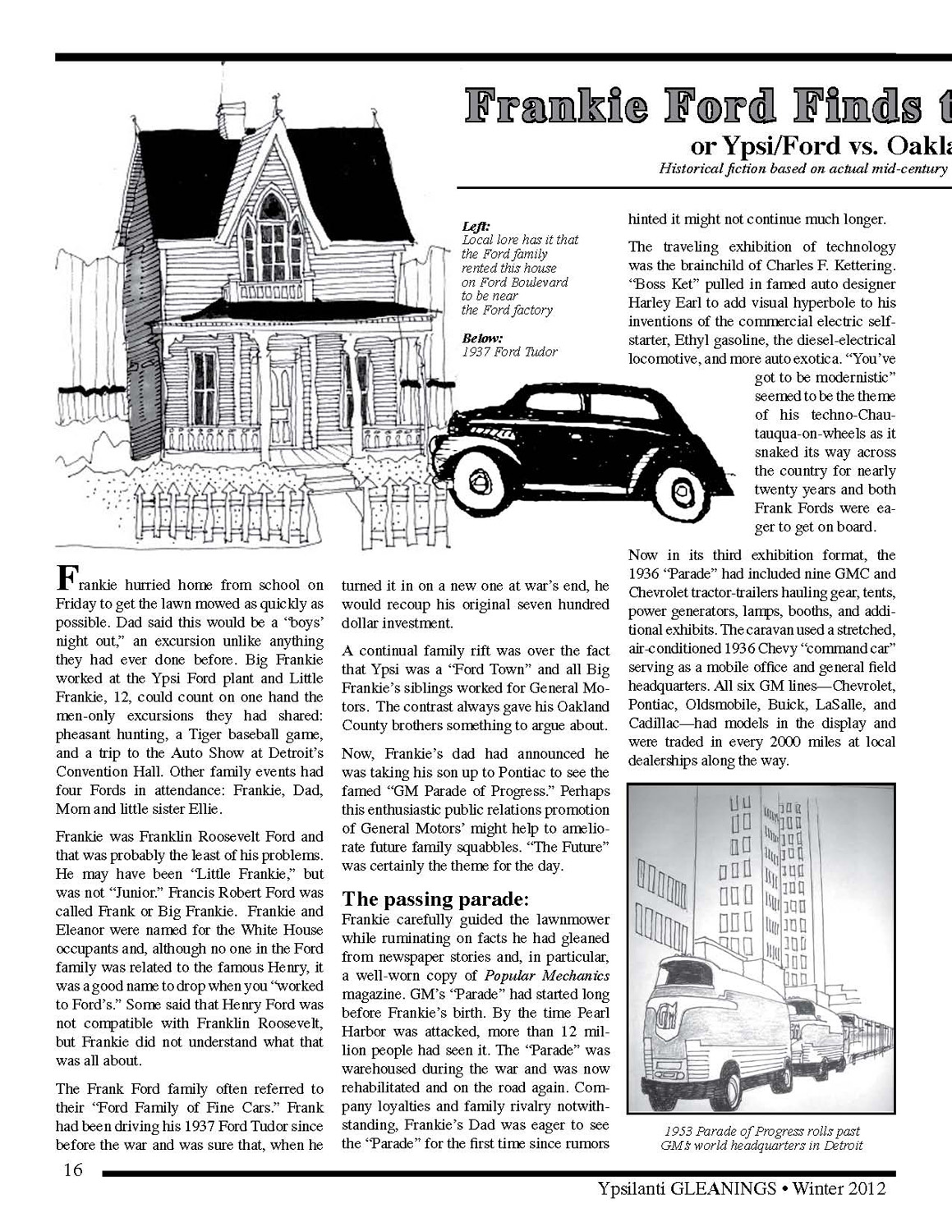

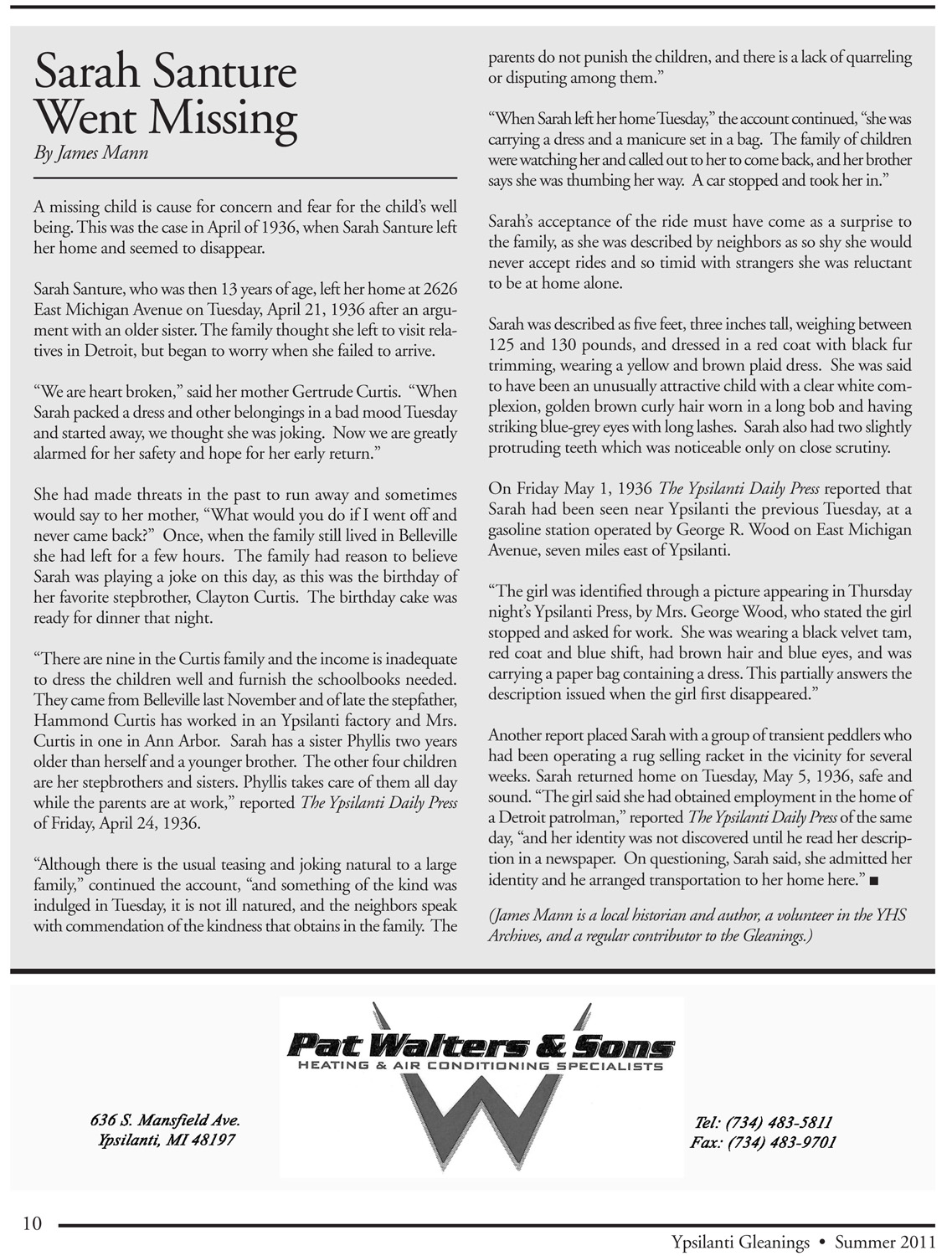

In the nineteenth century, the area around the railroad depot was the noisiest, busiest spot in Saline. Steam engines puffed in six times a day to drop off and pick up people and freight. Nearby were a busy grain elevator, two barns, a blacksmith shop, and a lumberyard.

Today the tracks are gone, replaced by a quiet walking trail. On September 24 a ribbon-cutting ceremony marked the official opening of the path that runs along the old railroad bed from Ann Arbor Street to Harris Street past the former depot, now a museum operated by the Saline Area Historical Society. Though the path is less than a quarter mile long, there's hope that it will be the fast leg of a much longer trail.

Saline's first train arrived in 1870 on the Detroit, Hillsdale, and Indiana line (DHI). "Detroit" and "Indiana" were both wishful thinking: the line ran only from Ypsilanti to Bankers, a little town west of Hillsdale. But it connected with the Michigan Central Railroad in Ypsilanti, the Ann Arbor Railroad at Pittsfield Junction south of Ann Arbor, and the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern in Hillsdale.

Although not a major line, the DHI was important to Saline, allowing local farmers to ship wheat, oats, apples, wool, and livestock to larger markets. Saline was the state's busiest shipping point for animals during the nineteenth century, says Saline historian Bob Lane. Livestock were herded down unpaved Bennett Street and held in pens on the south side of the depot. In 1875 the Saline Standard Windmill Company began making windmills and pumps, and the railroad made it a nationwide business.

The barn closer to the station is listed on maps as a hay and fertilizer warehouse. The other was operated by Gay Harris and Willis Fowler, who would buy wool from local sheep raisers and store it until they had enough to send a train car load to wool mills. In mediate nineteenth century Washtenaw County was the nation's leading producer of wool.

A windmill between the station and the first barn pumped water into an underground tank, and from there to a water tower across the tracks. Steam engines filled their tanks from this tower. Around 1900, an electric pump replaced the windmill.

E. W. Ford's lumberyard was west of the station, occupying most of the land from there to the intersection of Ann Arbor and Bennett streets. South of the tracks, Hy Liesemer's grain elevator faced Ann Arbor Street According to an 1888 map, it could hold 10,000 bushels. North of the tracks was Feuerbacher's blacksmith and welding shop, run by John Feuerbacher, who came from Germany in 1870, and his son Edward. The Feuerbachers also bought and sold scrap iron behind the shop, shipping it out by train.

During the twentieth century, rail service declined. The depot saw its last passenger train in 1931; shortly after that, the passenger lobby was removed. Freight operations continued, but in 1961 the depot was closed completely.

Today all that survives is two-thirds of the depot. The wool barn burned down in the 1940s. The hay and fertilizer building has also disappeared, as have the windmill, water tower, lumberyard, grain elevator, and blacksmith shop. There's a small commercial area where the lumberyard stood, and an auto parts store at the blacksmith shop location.

In 1980, after a few years of intermittent use by a couple of businesses, the old, dilapidated depot was given to the Saline Area Historical Society. It looked like a shack, but the society lovingly restored it and made it into a museum.

Today the entrance is through a door that was once the interior entrance to the station agent's office. The bigger room beyond the office, originally the baggage area, is used for displays and meeting space.

The historical society brought in a real caboose, which schoolchildren love. A ten-foot windmill, similar to one that was there originally, was installed as an Eagle Scout project. Across the tracks you can still see traces of the water tower foundation. The society's president. Wayne Clements, would like to move another water tower there or reconstruct one.

Where the hay and fertilizer barn once stood, the historical society has moved a livery barn from 101 North Lewis Street, where Orange Risdon. the founder of Saline, once lived. A real Saline Standard windmill is stored inside.

The idea of a walking path along the old rail bed percolated for years, but it took a while for the society to reach agreement with the Ann Arbor Railroad, which owns the tracks. In November 2005 the society signed a lease with the railroad, and the project quickly gained support; its backers include the health promotion group Pick Up the Pace, Saline!

To cut costs, the organizers abandoned plans for lighting and paving the trail and used some volunteer labor. Washtenaw County Public Health contributed $18,170 from a state grant. Saline CARES (a millage that provides funding for recreational programs) awarded $8,000, while the City of Saline agreed to help cover interim costs.

Heritage Lawn Care, a landscaping firm on Wagner Road, offered a discounted price for installation. The company created a walking trail alongside the tracks by clearing out trees and other obstacles, leveling the ground, installing a landscape fabric, and laying six inches of limestone on top. The finished path is suitable not only for hikers but also for bicycles and wheelchairs.

The area between the rails was also cleared and filled with larger stones. "We thought delineating the tracks would make it more attractive," says David Rhoads, who led the volunteer effort. Hikers can see the challenge the work crews faced by looking at how much vegetation has overgrown the remaining sets of tracks to the north.

The clearing also made it possible to ride the depot's one-person handcar, which train employees used to check the tracks. Rhoads and Clements plan to work on repairing the switch at the Harris Street end of the trail so that the handcar can make a round trip from the depot.

Future plans include adding benches and trash receptacles along the trail. The Saline Garden Club is preparing to plant a perennial garden made up mainly of native plants in a clearing next to the tracks. Other ideas in the talking stage include installing art along the path and putting in bike racks that look like steam engines.

The organizers hope to extend the trail east to the Saline District Library on Maple Road and west to Mill Creek Park. The western end would run near Brecon Village Retirement Community and pass a gorgeous trestle now hidden in the woods. Some neighbors along the route have objected, though, so the plan's future is uncertain.

—Grace Shackman

Turning the clock ahead in Dexter

From car showroom to coffee shop

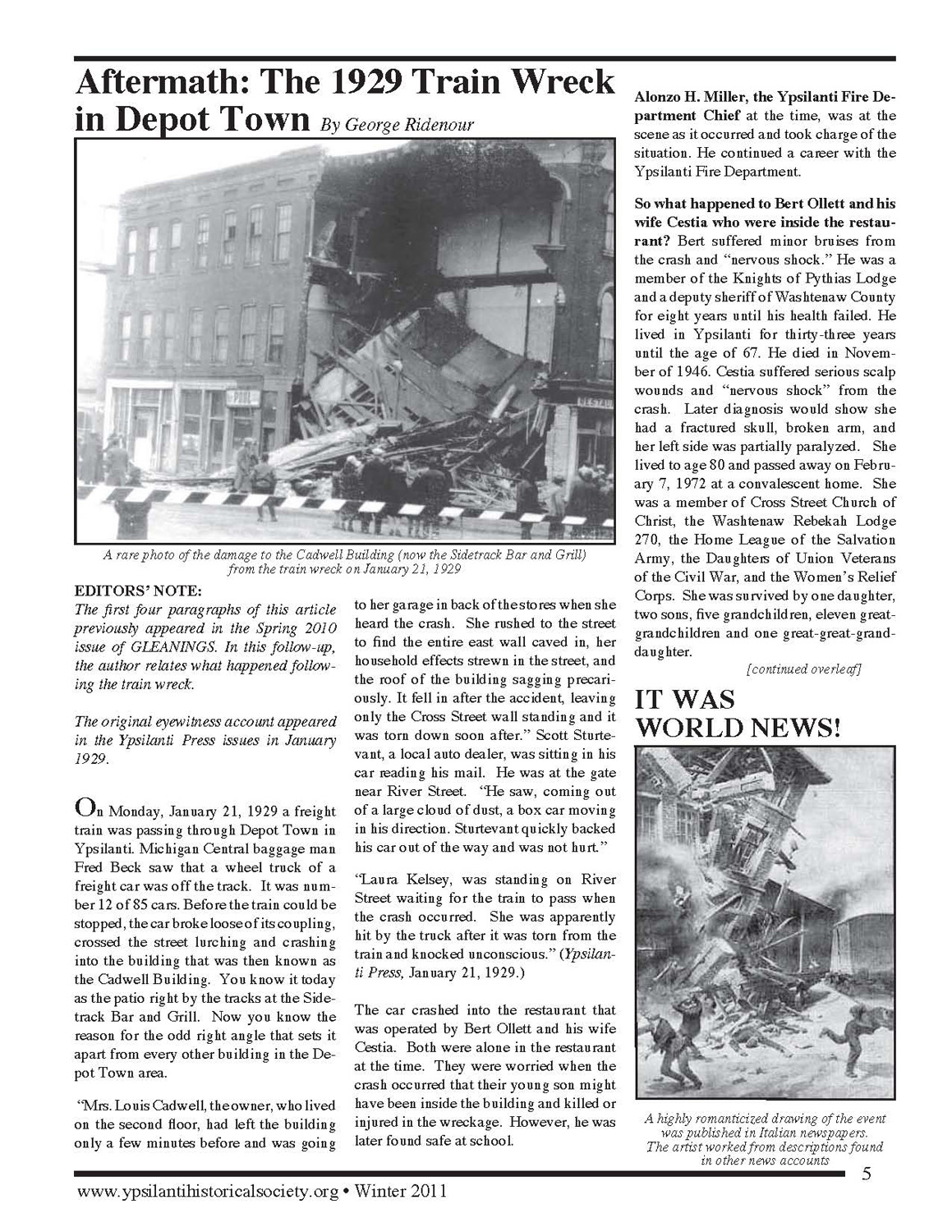

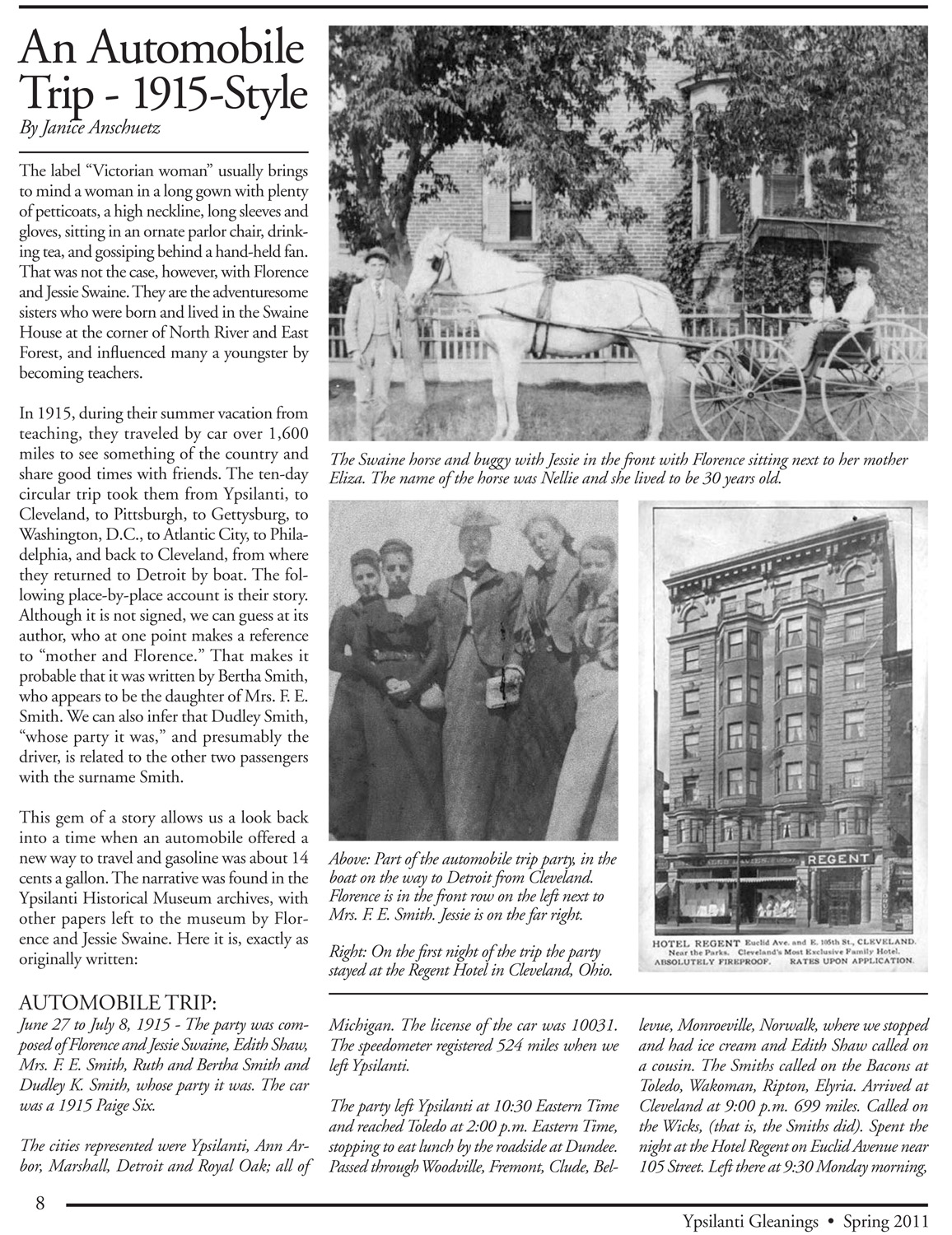

Before car salesrooms and gas stations were relegated to the outskirts of town, Ralph Kingsbury's Ford dealership stood on the corner of Main and Broad streets in Dexter. Today the building is the Clock Works Coffee house.

"It's as different as you can get in the same space," says Elizabeth Kingsbury Davenport, Kingsbury's daughter. The Clock Works, although located in the former dealership's post-Civil War Commercial Italianate building, manages to look very modem and airy with exposed brick walls, scenic watercolors, and generously spaced tables and chairs.

In Davenport's time, when her father's business included the main storefront, a garage on the east, and gas pumps on the west, this same site was anything but open: a single Ford floor model took up most of the showroom, surrounded by vats of car parts, barrels of freebies for the gas station, and cane-bottom chairs for people to sit on while they waited for their cars to be repaired.

Harvey Blanchard opened Dexter's first Ford dealership in 1911. Ten years later he started a bus line between Ann Arbor and Dexter using Fords. In 1926, in the last years of the Model T, Blanchard gave up the car business and Kingsbury took over.

"He always loved cars," recalls Davenport of her father. "He drove a Studebaker, but the Dexter Ford dealership was open and his mother bought it for him."

Kingsbury had graduated in 1912 from the U-M's railroad accounting program, the precursor of today's business school. He had been working for the Pere Marquette Railroad in Detroit when the opportunity arose. He moved to Dexter with his wife, Marian, who became the local piano teacher; their three young children, Elizabeth, Doris, and Stewart; his mother, Loretta Kingsbury; and his mother-in-law, Jennie David. They were later joined by his brother-in-law, William David—"Uncle Will," as Davenport knew him.

The new ownership was celebrated with a grand opening. The building was decorated with red and white flags furnished by the Ford Motor Company, and salami, liverwurst, cheese and crackers, and pop were served inside. According to Davenport, the fanfare was probably a bit "too much" for local residents. "They were used to a quieter approach," she explains. "It was a farming community. There were some prosperous farmers, but it was not a rich community. People lived simply. They played cards on Saturday night; they went to weekly dances or church suppers."

If the opening sparked any resistance among members of the community, it didn't affect the business, which grew big enough to employ three mechanics, two salesmen, and a bookkeeper. Davenport remembers her dad sitting at his Mission-style desk in the back of the store wearing a green visor and cooling himself with a palm-leaf fan. In front of him stood the dark green metal counter. With an old-fashioned cash register and a Philco beehive radio. Uncle Will, a short man who always wore a hat—either a fedora or, in summer, a straw boater—managed the two gas pumps (regular and ethyl), although "whoever was around did the gas. They didn't exactly line up for service," Davenport says. To keep customers coming, premiums were given for buying certain amounts of gas. Davenport remembers Depression Glass dessert plates, cups and saucers, creamers, sugars bowls, and salad plates, later replaced by lacy pressed glass that was a yellow-amber color, a light green, or pink.

The store itself was decorated in "Ford Motor olive drab," recalls Davenport. The company had a standard look for its showrooms and sent out posters of cars, large cardboard cutouts of cars, ad materials, and flyers, things that all Ford dealers were expected to use. The repair area (now a video store) was connected to the salesroom by a side door; it had roll-up garage doors on the street, an oil-change pit (hoists were rare in those days), and a back door large enough for cars to exit to the alley.

In the early days of the dealership, Kingsbury sold one car at a time—after a customer bought the floor model, he would order another. Occasionally a Fordson tractor or an additional car or two would be on display outside near the gas pumps.

Later Ford switched to a quota system, sending a car hauler with Kingsbury's assigned delivery. New models were celebrated at the dealership with blue and white triangular banners, while yellow banners were used for special sales. Davenport still remembers the day in 1927 when the Model A was introduced: "I went to the candy store and told them it went sixty miles an hour. They didn't believe me."

Once a month the Ford road man came and inspected the books, an event that Davenport recalls as "always stressful." Henry Ford's visits were even worse. He and his henchman, Harry Bennett, would park in front and "sit and watch," she remembers. "It was like God watching. We were paralyzed with fear and not allowed anywhere near them."

When the Great Depression hit, it was harder to sell cars. "Dad sold a lot of cars to U-M faculty and to his frat brothers or their friends. The repair work was for Dexter folks," recalls Davenport. Area farmers needed to keep their old trucks and tractors running and would sometimes bring them into the dealership "literally held together with baling wire. Dad had a soft heart and knew you couldn't farm without gas. Some people paid their bills with in-kind goods instead of money, a practice frowned on by Mr. Ford, but we ate very well," she says.

During the depression the car dealership was also the repository for surplus food, which was lined up against the west wall. People came in and signed for the food they took. "I was embarrassed that people had to come in and pick up food. I'd always make myself scarce when I could," recalls Davenport.

Kingsbury moved the dealership twice, each time to bigger quarters—first to the top of Monument Park in the building now home to Cottage Inn pizza, and then to the top of the hill, now an AAA office. In 1941 he sold the business to Al Gross, who had been a salesman with him from the beginning. Kingsbury took a job as bookkeeper at the Buhr Tool Company in Ann Arbor, where he worked until he retired. He died in 1976.

After Kingsbury moved out of the Blanchard building, it stood empty until 1944, when Art Lovell moved his appliance store into it from across the street. Lovell, an excellent mechanic, kept the garage as a car repair place and continued to run the gas station, although he changed it to a Dixie Gas station, supplied by the Staebler Oil Company of Ann Arbor. He used the storefront to sell Frigidaire appliances. As engines improved and cars needed fewer overhauls, he segued into doing more appliance repair.

Kate and Mike Bostic opened the Clock Works Coffee Shop in the building in 1997. They survived the first two years despite heavy construction going on around them. "Fortunately we're serving an addicted population," laughs Kate. In addition to coffee the Bostics serve morning snacks and light lunches. They are obviously filling a community need; people come in on the way to work, parents stop in after dropping their children off at school, and local merchants come in for lunch. In warm weather, people can drink their coffee at tables on the side of the building where the gas pumps once stood.

In one respect the present operation is not as divergent from the car dealership as it seems. Davenport recalls that when her father ran the place people came in throughout the day, some waiting for their cars to be fixed, others stopping in if they were buying gas or just passing by. Although the dealership didn't serve coffee (as many do now), "there were newspapers to read," says Davenport. Or, she adds, people would simply drop by, coming in to "sit and talk"—just as they do at the Clock Works today.

—Grace Shackman