U-M Goes Nuclear: The Michigan Memorial Phoenix Project

Origins: From J-Hop Raffle to Functional Memorial

It was December 1946 -- just over a year after the end of World War II -- and University of Michigan students were excited to bring back the highly popular Junior Hop (J-Hop), a glittering three-day student formal started by fraternities in the 1860s that included dancing, morning-after breakfasts, hayrides, and house parties. This year's lineup featured big band leader and saxophonist Jimmie Lunceford, and former star trumpeter with the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra, Ziggy Ellman. However, many students were concerned that such frivolity clashed with the tenor of a world so recently ravaged by war. As a result, the J-Hop Committee persuaded the Student Legislature to turn its traditional J-Hop raffle into a fundraiser for a living memorial, and a student committee urged the University regents to adopt a resolution to pursue the idea of such a functional memorial.

Functional - or living - memorials were becoming increasingly popular after World War II as a more palatable alternative to the traditional statue or obelisk associated with memorials of earlier generations. The J-Hop committee’s initial idea was to build a chapel or recreation building in the Arboretum.

By January 1947, there was considerable enthusiasm for the project -- especially among the burgeoning World War II student veterans taking advantage of the G.I. Bill (of the 18,000 U-M students at the time, 12,000 were WWII veterans) -- and this prompted the creation of a significantly larger joint student-faculty-alumni fundraiser and the J-Hop raffle funds were turned over to this effort. An executive committee was formed that included a central committee of all student organizations; a sub-committee of the student legislature; and a faculty-alumni advisory group.

Thus began the University’s first major fundraising effort to date.

The Board of Regents unanimously approved this yet-to-be-named project upon the recommendation of U-M President Alexander Ruthven. Ralph Sawyer, Dean of the Rackham Graduate School, took up the initiative by appointing a War Memorial Committee. Among this committee's members were three WWII veterans: Arthur DerDerian, an aviation cadet; Arthur Rude, a first lieutenant in the Army; and E. Virginia Smith, a nurse in the Pacific Theater.

Harnessing Atomic Energy for the Greater Good

But what would this memorial look like and how would it function? What would it be called?

War Memorial Committee chair and Dean of Students, Erich A. Walter, approached several friends and former alumni. The University also sent letters to world leaders, authors, and stars -- figures such as Winston Churchill, Bertrand Russell, C. S. Lewis, E. B. White, and Orson Welles -- seeking advice and input.

But it was Fred Smith, a 39-year-old U-M alumnus and New York publishing executive, whose proposal for the memorial most engaged U-M’s student body and administrative leadership. His idea? To harness the power of the atom for the greater good. He wrote, “As vital to the future of mankind as the continuation of religion; and the devotion of the people involved in it should be no less unstinted... We have named the memorial The Phoenix Project because the whole concept is one of giving birth to a new enlightenment, a conversion of ashes into life and beauty.”

The Michigan Memorial Phoenix Project (MMPP) would be "a living, continuous memorial" - a unique endeavor dedicated to exploring ways that the atom could aid mankind rather than destroy it. The MMPP was created by action of the U-M Board of Regents on May 1, 1948, and in his Memorial Day address that year, U-M President Alexander Ruthven called it “A memorial that would eliminate future war memorials.”

The idealism was matched only by its danger: To bring such a destructive force to a college campus with the intent of harnessing its power for the benefit of mankind was a radical idea requiring a radical approach.

"The most important undertaking in our University's history."

Under the leadership of National Executive Chairman Chester Lang, the Phoenix Campaign grew into a national effort that would be the first significant fundraising campaign initiated by the University -- at the time "the most important undertaking in our University's history," according to Ruthven. The Michigan Memorial Phoenix Project Laboratory would eventually be funded by over 30,000 alumni and corporate donors. By 1953, the campaign raised $7.3 million for a research building and endowment eventually amounting to over $20 million.

The project would mark many firsts:

* The first fundraising effort in U-M history

* The first set of laboratory buildings on the new U-M North Campus

* The first university in the world to explore the peaceful uses of atomic energy

* And it would initiate the U-M’s new Department of Nuclear Engineering and Radiological Sciences, the first such university program in the world

“M Glow Blue!” Henry Ford Donates a Nuclear Reactor

The Ford Motor Company alone donated $1 million to build the Ford Nuclear Reactor (FNR) as part of the Laboratory.

In February 1955, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) licensed the Ford Nuclear Reactor (FNR) and construction on the reactor began later that summer. The reactor would be built in a special unit at the north end of the Laboratory and it was the first reactor ever requested for construction by an agency other than the AEC. The FNR was dedicated on November 16, 1956, reaching its first critical mass on September 19, 1957, and level 1 megawatt on August 11, 1958. Eventually operating at two megawatts of power, the “icy blue glow” of the more than 55,000-gallon reactor pool inspired the motto of the reactor workers: “M-Glow Blue!”

Moreover, the Department of Energy would fabricate, transport, and dispose of the fuel at no cost to the University.

U-M professor of electrical engineering Henry Gomberg was the first director of the Phoenix Project. And the College of Engineering was responsible for developing its instructional and research program. The FNR would operate 24 hours per day for the next 50 years.

Bubble Chambers and Mummies: Research at the Phoenix Laboratory

Research at the Laboratory took place across multiple disciplines, helping to fund studies on the applications of nuclear technology in fields as diverse as medicine, chemistry, physics, mineralogy, archeology, engineering, zoology, anthropology, and law. It saw uses for cancer treatment, bone grafts, medieval coins, and even an Egyptian mummy.

Former MMPP director David Wehe remembers, “I recall lively lunchroom discussions with engine researchers from GM and Ford discussing measurement techniques with the nuclear chemists inventing new diagnostic pharmaceuticals and archeologists testing the authenticity of ancient relics -- all of them working within the Phoenix Memorial Laboratory.”

Project highlights include Gamma ray sterilization; carbon-14 dating; radioactive iodine for cancer treatment and detection; gravitationally-induced quantum interference, as well as the bubble chamber design allowing rapid, easily interpreted photographs of rare atomic interactions that won Donald Glaser a 1960 Nobel Prize in Physics. The laboratory also included a greenhouse and saw foundational research on the effects of radiation on plant life.

The FNR was also used to train utility workers in nuclear instrumentation and reactor operation and was visited over the years by world leaders and distinguished scientists such as Robert Oppenheimer and Hans Bethe. MMPP leadership was also instrumental in founding the International Cooperation Administration (ICA) arm of the AEC.

By June 1997, however, the Ford Nuclear Reactor Review Committee estimated the reactor was costing the university an average of $1 million a year and requested input from university departments, as well as organizations outside the university community, on continued use of the facility. Although many groups actively campaigned to keep the reactor operational, the decision was made to close it. The reactor took nearly a decade to dismantle and was officially decommissioned in 2003.

Rededicating the MMPP

After extensive renovations, the former Phoenix Memorial Laboratory in 2013 became the home of the U-M Energy Institute, which continued to support the Project’s unique memorial mission. In spring 2017, after a decade of dismantling the FNR and clearing the building of radiation, the building was rededicated as the Nuclear Engineering Laboratory with a focus on advancing nuclear security, nonproliferation, safety, and energy. In 2021, the Energy Institute was disbanded and the Nuclear Engineering and Radiological Sciences (NERS) program regained proprietorship. In April 2019, the department launched the Fastest Path to Zero Initiative, with the mission of “identifying, innovating, and pursuing the fastest path to zero emissions by optimizing clean energy deployment through energy innovation, interdisciplinary analysis, and evidence-driven approaches to community engagement.” The Fastest Path offices are now housed within the MMPP.

A rededication of the MMPP took place in 2022. The labs and offices are occupied by two groups: NERS and the Materials Research Institute (MRI).

According to former MMPP director David Wehe, “Today, the MMPP continues its legacy of honoring WWII veterans by providing seed funding to researchers seeking to harness the atom for the public good. While the building also serves other purposes now, the hall still echoes those exciting discoveries that came from the MMPP.”

Historical photos and articles about the Michigan Memorial Phoenix Project

The M.U.G. (Michigan Union Grill) in the 1950s-1960s

Although an affluent community like Ann Arbor was hardly the culture in which ‘The Beat’ movement (theoretically) thrived and was designed for, nonetheless the influence of ‘The Beats’ was present and very much felt in Ann Arbor back in the late 1950s and the early 1960s, student poets and hanging out.

The October 15, 1969 Peace Rally

The peace rally at Michigan Stadium on October 15, 1969, was the largest of all the anti-war protests in the 1960s in Ann Arbor. Including some 20,000 attendees, the rally was the culmination of Ann Arbor’s participation in a nationwide event - The Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam - that took place that day, with many businesses, churches, and colleges across the country closing to protest continued involvement in the War. Related events at the University of Michigan included teach-ins and forums, and the day concluded with a 6 p.m. torchlight parade winding from the University of Michigan central Diag to Michigan Stadium, followed by a rally inside the Stadium.

Rally organizers were New Mobilization leader Douglas Dowd of Cornell University and Ann Arbor Mobilization leader Eugene Gladstone. Speakers included U.S. Senator Philip A. Hart; SDS founder and Chicago 8 member, Tom Hayden; U. S. Representative John Conyers; State Senator Coleman Young; State Representative Roger Craig; Eugene Charles of the Black Panthers; Rhoades W. Murphy, U-M geography professor; and Ann Arbor City Councilman for the Third Ward, Nicholas Kazarinoff. The local rock band SRC performed at the Rally. Both the U-M parade and rally remained peaceful, a minor incident occurring when a participant near the speakers' platform spit on speaker Tom Hayden and was removed by Ann Arbor police.

A month earlier, on September 19, in a speech at Hill Auditorium during the “Tactic-In” events on the University of Michigan campus, U-M President Robben Fleming came out against the war in Vietnam and promised to make University facilities available for the upcoming October 15 Moratorium. He further indicated that if enough people came out to express opposition to the War during the event, he would personally deliver their message to Washington. Fleming’s anti-war declaration was controversial at the time, as was his endorsement of a University venue for an anti-war protest; however, his decision, made on the heels of many contentious campus-wide protests that had occurred in preceding months - most significantly, the 1969 South University Riot - signaled his evolving belief that suppressing protests would only lead to violence.

In the days after the Moratorium, President Fleming remained true to his word and wrote a letter to Washington stating that the mood on the University of Michigan campus was one of “broad and deep opposition. This opposition is not simply emotional, it is thoughtful. It does not occur because of ignorance, but only after sober reflection.”

The 1969 South University Riot

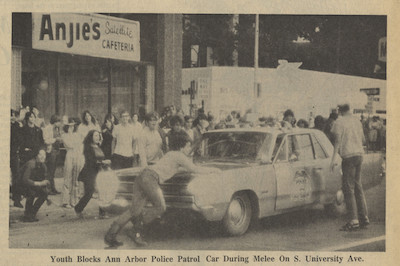

The 1969 South University Riot was a series of confrontations between local law enforcement and factions of Ann Arbor’s counterculture population that extended over three nights, from June 16-18, on or near the four-block South University Avenue shopping district in Ann Arbor.

Monday, June 16

Varying accounts in local and regional media make it difficult to determine exactly what occurred on the first night, June 16, but according to the Ann Arbor News, events began around 10:00 pm when an Ann Arbor police officer attracted a crowd of about 50 people while attempting to ticket a motorcyclist for stunt-riding in the street. The officer called for reinforcements and four additional police cars arrived, but when they eventually left without issuing the motorcyclist a ticket, the crowd -- now estimated at about 300 and comprised of various countercultural groups -- celebrated by staging a spontaneous "liberation party" and cordoning off a block of South University Avenue with tires, boards, garbage cans, and similar items.

Over the next few hours, the crowd swelled to somewhere between 500 and 1000, and members engaged in activities such as dancing, singing, drinking, and throwing firecrackers. Local newspapers also reported that a couple engaged in sexual relations in the middle of South University Avenue. During the revelry, Ann Arbor Police Chief Walter E. Krasny requested that both the Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Department and Michigan State Police be on standby in the nearby town of Ypsilanti. Plain clothes police officers were sent in to observe the crowd, but no tickets were issued out of fear that it would cause an “instant riot,” as Lieutenant Eugene Staudenmaeir told the campus newspaper The Michigan Daily. (Ann Arbor Police Chief Walter Krasny would later state that they declined to issue tickets because of “limited manpower.”) The crowd eventually broke up around 1:00 am, with some attendees returning to sweep up the debris and broken glass. Damages were minor, with some broken windows and slogans painted on parking signs and shop windows.

Tuesday, June 17

Although Monday’s event appeared to occur spontaneously, expectations were high for the next night, June 17, after some among Monday night’s attendees were overheard declaring they would attempt another street party on Tuesday at the same time and location. Furthermore, members of the White Panther Party, a local radical anti-establishment organization, issued a statement calling for the transformation of the South University Avenue shopping area into a pedestrian mall or “people’s park,” a pointed reference to the recent People’s Park movement in Berkeley, California that had been violently suppressed only a month prior. As a result, reporters from Detroit and further afield were in attendance that evening; and several high-ranking local officials, among them Washtenaw County Sheriff Douglas Harvey, Ann Arbor Police Chief Walter E. Krasny, and Prosecuting attorney William F. Delhey, made plans for a “show of force if the ‘street liberations’” took place.

Crowds began to gather in the early evening and by 8:00 pm attendees were participating in a variety of activities: Some erected a barricade of traffic cans, signs, and similar materials; two girls sat down in the middle of the street blocking a car; others set a fire in a garbage can. At around 9:00 pm the crowd had reached roughly 1,000 people, some of whom were merely onlookers hoping for a show. Deputy Police Chief Harold E. Olson attempted to disperse the crowd with the use of a bullhorn, but when he was met with resistance and shouted obscenities, riot-equipped officers from city and county agencies, including nearby Oakland and Monroe counties, were instructed to advance on the crowd, moving westward, with nightsticks, rifles held at port arms, and a half dozen crowd-control dogs from the Sheriff’s Department. Most of the crowd broke and ran, but a few people stood ground until they were seized and removed to an awaiting prisoner bus.

Further down the line, members of the crowd responded by hurling bricks, rocks, and bottles; some objects were thrown from the tops of buildings on either side of South University Avenue. Sheriff Harvey countered these efforts by ordering the firing of tear gas in their direction. Police cleared the street in roughly one hour, making 25 arrests, while some officers traveled further afield onto private property and the U-M campus, using tear gas and flares to illuminate gatherings that had reformed there.

Following the dispersal of the crowd, the area remained relatively quiet, with the exception of periodic police routings of stragglers, until around midnight when another crowd of about 800 gathered near U-M President Robben Fleming’s house a little further west on South University Avenue. Fleming appeared briefly, trying but failing to calm down the crowd. Ken Kelly, a staff member of the Ann Arbor Argus, an underground newspaper, also tried in vain to persuade the crowd to move away.

During this period, President Fleming also engaged in a heated conversation with Sheriff Harvey, urging him to exercise restraint. Deputy Chief Olson, the other key command officer on the scene, agreed to grant the president some time, but when one of his riot officers was hit by a brick thrown from the crowd, he and Sheriff Harvey ordered their officers to advance. With the crowd still throwing rocks and officers swinging clubs, the confrontation split into three segments, one moving west on South University Avenue, others moving north or south on East University Avenue, and officers pursuing factions down side streets.

By 2:00 am it was over, with 47 arrests. Roughly half of those arrested were charged with “contention in the street,” a misdemeanor; the other half were charged with inciting a riot, a violation of Michigan’s new riot statute that was put in place following the Detroit Riots in 1967 and which was punishable by up to ten years in prison and/or a fine of up to $10,000. Several persons arrested were treated at hospitals for injuries sustained by police, and fifteen police officers were injured by flying rocks, bottles, and, in one instance, a flurry of cherry bombs.

President Fleming and Ann Arbor Mayor Robert Harris quickly issued statements generally supportive of police action; however, Fleming suggested that the use of tear gas caused more excitement than it helped. Other attendees, including Detroit News photographer James Hubbard, disagreed with this assessment of the previous night’s police action, stating that it was worse than what he’d experienced first-hand during the 1967 Detroit Riots.

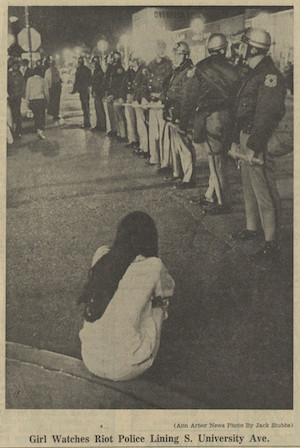

Wednesday, June 18

During the day on June 18, an ad hoc alliance of local radicals and student government officials (the Radical Caucus, Students for a Democratic Society, and the Rent Strike Committee) staged a rally on central campus attended by nearly 1,000 people, including President Fleming, who urged students to remain calm. Lawrence (Pun) Plamondon, a leader in the White Panther Party, spoke on behalf of the group and asked the audience for a vote on whether they should demand that South University Avenue be closed immediately to make a pedestrian mall. The vote was turned down.

Meanwhile, hoping to avoid another night of conflict, university and city officials scheduled a free rock concert for 8:30 pm in Jefferson Plaza near the U-M Administration Building. During the concert, which was attended by roughly 2,000 people, Mayor Harris addressed the crowd, promising to appoint a special City Council committee to look into the viability of creating a pedestrian mall on South University Avenue or elsewhere in the vicinity. Several other university and city officials, including most members of Ann Arbor City Council, circulated among the crowd to talk with attendees and urge restraint.

There was no police presence at the concert. However, across town on South University Avenue, in anticipation of repeated conflict in that area, law enforcement presence included 300 police officers from six different agencies, an armored car with machine guns, and a police helicopter overhead.

No confrontations occurred during this period on South University Avenue, with most newspaper accounts describing a festive atmosphere and crowds diminishing by 11:00 pm. Shortly thereafter, however, a crowd once again began to form, blocking traffic in the street. When university officials and local clergy both failed to break it up, Deputy Chief Olson ordered roughly 200 police officers to either end of South University and, using a pincer movement with rifles leveled and bayonets fixed, closed in on the crowd.

20 arrests were made and two civilian injuries reported, including that of Dr. Edward Pierce, a physician, former Ann Arbor City councilman, mayoral candidate, and local Democratic Party chairman, who had attended at the request of U-M students for a trained medical presence. Dr. Pierce stated that police knocked him to the ground, struck him repeatedly with billy clubs, and dragged him 30 yards to the prisoner bus. Police claimed in return that Dr. Pierce had crossed the line of officers. He was arrested on a felony riot charge that was dropped the next morning.

Thursday, June 19, and the Aftermath

Although the atmosphere on South University Avenue remained somewhat tense on the following evening, Thursday, June 19, and police were held in a staging area nearby, city and university officials gambled that civilian peacekeeping efforts would be more effective than a show of police force - and their gamble paid off. Crowds thinned out by midnight and dispersed for good around 2:00 am when it started to rain heavily.

By most accounts, the confrontation between local law enforcement and factions of Ann Arbor’s counterculture - what the Detroit Free Press called “The Battle of Ann Arbor” - was a draw. Officials looking into the cause of the riot would later suggest that some attendees in the crowd that first night, June 16, may have been motivated to act out of frustration after attending a City Council meeting earlier that evening where they learned their favorite rock concerts at West Park would be canceled due to citizen complaints. However, the consensus seems to be that what started in the spirit of fun, or even frustration, never amounted to a serious or calculated take-over of South University property, despite attempts by more radical elements among the crowd to turn events in that direction.

The left and right were also divided on the use of police force. Letters to the city's newspaper, The Ann Arbor News, were strongly pro-police; whereas letters to the university’s student-run newspaper, The Michigan Daily, where almost universally anti-police and, in particular, anti-Sheriff Douglas Harvey. Ann Arbor Mayor Robert Harris was attacked from both sides - from the right for not hitting hard enough and from the left for not doing enough to hold back the police.

Learn More

Harper's Weekly on Professor Adams.

Harper's weekly on Prof. Adams.

Under the caption "The new president of Cornell," Harper's Weekly has the following on Prof. Adams' recent good fortune:

Charles Kendall Adams, professor of history in the University of Michigan, was on Monday, the 13th, elected president of Cornell University, in the room of the retiring President White, by an almost unanimous vote of the trustees, the numbers being 13, to 3 for General Morgan. The new president, who is a native of Vermont, in which state he was born in 1835, owes this flattering election to the influence of the late president, between whom and him the most intimate relations existed during their acquaintance at Ann Arbor, where Professor Adams graduated in 1861, and where Professor White is the chair of history when the latter accepted the presidency of Cornell. Professor Adams id the author of "Democracy and Monarchy in France," and of the "Manual of Historical Literature," comprising descriptions of the most important histories in English, French, and German, together with practical suggestions as to methods and course of historical study, and of which the philosophic character, the profundity of learning, and judicious historical conclusions have given him high standing as a author. At the meeting of the trustees numerous tributes were received, speaking in the strongest terms of testimony to his executive ability and his thorough knowledge of educational systems both in this country and in Europe. The new president, indeed, is generally conceded by scholars to posses qualities of that sterling and lasting kind which, although not showy or brilliant at first sight as those which might be possessed by others, would yet tend to impress the board of trustees and alumni more and more as they know him better and more closely, and through his new position, with an increasing conviction of his scholarship, executive ability, and wide range of educational thought and experience. He has really been the responsible promoter of most of the successful plans of higher education at Michigan University, though others have received the larger share of the credit, and it was entirely through his exertions that the library system at Ann Arbor was built up; and those -- and they are many -- who are not willing to give him credit for the necessary force of character, will find themselves most grievously mistaken.

The Lost University - The Forgotten Campus of 1900

Ann Arbor today would be just another small Michigan town- no bigger, perhaps, than Saline or Chelsea- had it not been for one crucial event: in 1837, just thirteen years after its founding, it was designated the site for the University of Michigan.

The initial campus, situated on forty acres donated by the Ann Arbor Land Company, was a tiny affair, consisting of one combination classroom building and dormitory along with four professors' houses. The president's house on South University is the lone survivor from that first generation of campus buildings. Though still used as a residence, it has been vastly altered over the intervening 160 years.

The "Diag" took its name from the diagonal walk that crossed what was then largely an open field. But the campus grew quickly, particularly under dynamic presidents Henry Phillip Tappan (1852-1863) and James Burrill Angell (1871-1909).

Except for Tappan's observatory and Angell's Catherine Street hospitals, almost all of the nineteenth century construction took place on the Diag. By the turn of the century, campus was thick with structures, most built of a red brick in a weighty Romanesque style.

Almost all were swept away as the U-M's growth accelerated in the twentieth century. The Diag was completely rebuilt, and surrounding properties were acquired to extend the university's presence far beyond the original campus borders. Today only tiny Tappan Hall, hidden away between the art museum and the president's house, survives as a reminder of the red-brick campus of 1900

When James Burrill Angell arrived as president in 1871, the U-M had nine buildings. He oversaw the addition of fifty more before stepping down in 1909. The elegant oval shape of Angell's 1883 University Library had been truncated by the turn of the century with the addition of new book storage "stacks" at the rear of the building (left), but a gracefully curved reading room still looked out on the center of the Diag. Though the older portions of the building were torn down in 1918, the stacks were incorporated into the present Graduate Library, completed in 1920.

The Waterman and Barbour gymnasiums, at the comer of North University and East University, were the longest-lived of Angell's great red brick buildings. Their demolition was also a turning point in campus interest in historic preservation. In 1976, when the university announced its intentions to tear down the historic complex, a group called the Committee for Reuse of the Barbour-Waterman Buildings was established and lobbied hard for the university to take another look at alternative uses for the structures, which dated to the 1890s. Petitions were circulated and signed by thousands, citizens wore buttons saying "Recycle Barbour-Waterman," and many spoke before the regents to urge reconsideration.

The regents were not swayed, and the buildings were demolished in 1977 (their site is now part of the chemistry building). But the university has since shown greater sensitivity to historic buildings. And one unexpected result of the regents' intransigence on Barbour-Waterman was the listing of the entire original Central Campus, and other significant buildings such as Rackham and the Law Quad, on the National Register of Historic Places.

President Tappan's Law Building stood at the corner of State and North University. It was completed in 1863, the same year that the U-M's visionary founding president was fired by the regents (see "President Tappan Fired" in "The Top Ten Ann Arbor Stories of the Millennium," p. 31).

The formidable turret was added in a remodeling in 1893 but didn't quite make it to 1900—it was removed during another expansion in 1898. After completion of the Law Quad in the 1920s, the building was renamed Haven Hall and used for LS&A faculty offices. In 1950, a disgruntled student determined to obliterate a bad grade burned it down.

The modern Haven Hall is closer to the center of the Diag. The place where Tappan's Law Building stood is now a lovely, tree-shaded lawn.

When it opened in 1881, the U-M's natural science museum was the first owned by a public university. Designed by architecture prof William LeBaron Jenney—later

famous as the "father of the skyscraper"—the museum had a collection ranging from stuffed animals to Asian manuscripts.

The exhibits moved to the present Ruthven Museums Building in 1928. Jenney's building housed the Romance language departments for three decades before being demolished in 1958.

Exceot for the crowning dome, this long, massive building parallel to State Street bears an uncanny resemblance to Angell Hall. University Hall, completed in 1871, was the U-M's first great classroom building. The impressive dome shown here was actually the building's second- the first was deemed structurally unsound and replaced in 1896. Hidden from State Street when Angell Hall was built directly in front of it in 1924, University Hall lingered on for another twenty-six years before being torn down in 1950.

Stretching the tum-of-the-century date slightly, this multipanel postcard shows the U-M's hospitals as they stood following completion of the Palmer children's ward in 1904. One of the two hospitals flanking the Palmer ward had been built for the U-M's medical doctors, the other for its homeopathic physicians. By 1900, however, the homeopaths had moved out to a new hospital on North University.

The low, many-windowed "pavilion" hospitals reflected the emerging medical thinking of the nineteenth century before the role of germs was understood, disease was thought to be spread by "morbid" air exhaled by sick patients. It wasn't a bad guess, since it led to the division of hospitals into isolated, well-ventilated wards—steps that did help reduce the rate of hospital-induced infections.

By the turn of the century, the germ theory and antiseptic surgery were fueling great strides in health care. The homeopaths soon faded, while the M.D.'s moved into a succession of huge new hospitals—on Ann Street in the 1920s, and overlooking Fuller Road in the 1980s. The site of the old pavilion hospitals is now occupied by the Victor Vaughan Building, Med Sci II, and the Taubman Medical Library.

An impressive testimonial to the growing importance of the physical sciences, the 1885 Engineering Laboratory bore a striking resemblance in both style and scale to the University Library just to the north. It was designed by Gordon Lloyd, the celebrated Gothic architect best known locally for his work on two prominent churches, St. Andrew's and First Congregational.

The engineers expanded into larger quarters bordering the southeast comer of the Diag (home of the famous "Engin Arch"), then leapfrogged East University, and finally relocated en masse to a still-growing complex on North Campus. By then the 1885 laboratory was long gone—it was torn down in 1956.

As the university expanded in the early twentieth century, it acquired and demolished many of the buildings that had bordered the original campus. Between 1909 and 1920, the university gained title to some 114 separate parcels of land, including the Arboretum, the Botanical Gardens off Packard Road, and the site of the power plant on Huron Street. But perhaps its most dramatic acquisition was professor Alexander Winchell's spectac-ular octagon house on North University.

Winchell served at various times as professor of geology, zoology, botany, physics, and engineering. The strong-minded Winchell was one of president Tappan's most vociferous opponents but also a powerful advocate of opening the university to women, and perhaps America's most influential supporter of Charles Darwin's then-novel theory of evolution. His unusual octagon home, built according to the tenets of Orson Fuller, a well-known phrenologist and prolific writer on health, happiness, and sex, was surrounded by extensive gardens that complemented his collections of flora and fauna, some of which are now at the Smithsonian.

After Winchell left the university in the mid-1870s, his home was rented by various fraternities. Acquired by the university in 1909, it was demolished shortly afterward to make way for Hill Auditorium.

The original professors' residences from the 1840s found new uses as the campus grew. This one facing South University housed the Dental College from 1877 to 1891, adding a wing (right) in the process. The engineering department took over in 1892 and stayed until 1922. when the building was demolished to make way for the Clements Library.

The U-M Law Quad has a timeless feel, but in fact it is of comparatively recent construction. Two entire blocks of residences were demolished in the 1920s to make room for it. One of the more spectacular of the buildings lost was the 1880 Psi Upsilon fraternity house, which faced South University at the comer of State. A newspaper account from June 30, 1923, noted that "since the beginning of the second semester men have been tearing down the former fraternity houses on State Street, which occupied the land needed for the new [Lawyers] Club. Practically all of the work of the demolishing of the Psi Upsilon house has been completed and the steam shovel will clear away the remainder of the ruins. . . . Practically all of the homes in this block are now being torn down."

Until recently, it seemed that the same fate might befall the row of four nineteenth century houses the U-M owns on Huron across from the Power Center.But after years of designating the location as a future building site, the university is now renovating and rehabbing the houses—an encouraging sign that it has finally begun to develop a preservation ethic.

Learning from the Halo

Burned by the firestorm over its controversial Michigan Stadium halo, the architectural firm of Venturi, Scott Brown & Associates is taking a much more conservative tack with its first U-M building.

The Philadelphia firm, headed by the husband-and-wife team of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, is nationally famous for daring designs. When U-M president Lee Bollinger hired VSBA to work on a campus master plan two years ago, one of their first suggestions was to ditch the traditional brick trim planned for the expanded stadium in favor of a maize-and-blue metal halo decorated with gigantic football icons and slogans. The couple, authors (with Steven Izenour) of Learning from Las Vegas, thought the colorful band would, in Venturi's words, "create a gala quality at that end of campus."

They quickly discovered that to many people Wolverine football is more than a game. Infuriated at the halo's breezy irreverence, football fans protested verbally, wrote angry letters, and withheld donations. This past spring, Bollinger finally caved and had the halo taken down.

So when Venturi presented plans for his first U-M building to a group of community leaders in April, the first question on everyone's mind was, Could this be another disaster? Those concerns were soon allayed: presenting the plans for the U-M's new Life Sciences Institute building, Venturi took pains to show how it would fit with the rest of the campus.

After Scott Brown gave an update on the campus plan, Venturi, wearing his usual professorial scruffy sport coat, diffidently held up two poster boards. The audience impatiently craned their necks to see, and then laughed as mayor Ingrid Sheldon stepped forward, seized the boards, and lifted them high overhead. One showed the proposed institute, which will face Washtenaw at an angle south of Palmer Drive. The other compared the new design with similar buildings already on campus.

While saying that he doesn't consider himself a "historical revivalist," Venturi stressed that he does believe that new buildings should harmonize with their surroundings. He called his six-story Life Sciences design "a generic loft building, like the early buildings on campus by Albert Kahn and Smith, Hinchman & Grylls." The simple, functional designs of Albert Kahn (architect notably of the Hatcher Library and Hill Auditorium) and SHG (Chemistry Building, Rackham Auditorium) still look good many decades after they were built, and have proven themselves highly adaptable to changing academic needs—goals that Venturi says he aspires to as well.

The regents approved the Life Sciences Institute plan at their April meeting and went on to appoint VSBA as architects for the Commons—the second new Life Sciences building, which will face Washtenaw in front of the power plant. If VSBA succeed, as they have elsewhere, in combining classic elements in new and unusual ways, they may well be remembered for their U-M buildings long after the halo fiasco is forgotten.

The Latke versus the Hamantasch

Sophisticated debates on a silly subject

The latke and the hamantasch, two traditional Jewish holiday foods, were also the unlikely subjects of debates held at the U-M Hillel Society in the 1960s and 1970s and then at the Jewish Community Center from 1988 to 1994.

"It was absolutely nothing serious," recalls participant Chuck Newman. Each dish had two defenders who would argue for the superiority of their chosen food, often citing evidence from their professions or specialties.

"Sophisticated people arguing in a sophisticated way on a silly subject" is how longtime moderator Carl Cohen, a U-M philosophy professor, describes the events.

The latke, a potato pancake, is often eaten at Hanukkah, a Jewish festival celebrated in December. Because it's cooked in oil, it's considered a symbol of the one day's supply of oil that miraculously kept a menorah burning for eight days after a Jewish army took Jerusalem back from the Syrians in 165 B.C.

The hamantasch, a three-sided pastry filled with prunes or poppy seeds, is eaten at Purim, which falls in February or March. It is meant to resemble the hat worn by Haman, who advised the Persian king Ahasuerus to destroy the Jews; his plot was thwarted by the queen, Esther, who was a Jew.

The idea of-the holiday debate originated at the University of Chicago and quickly spread to other campuses. Herman Jacobs, head of Hillel at the time, introduced it to Ann Arbor in the 1960s.

Cohen recalls that he chose participants for their "willingness to engage in whimsy—flights of fancy—and be downright silly." The debaters lived up to that mission. Computer scientist Bernie Galler remembers that the late James McConnell, psychologist and editor of the Worm Runners Digest, talked of the effects of feeding prunes to his rats. McConnell packed the audience with friends wearing T-shirts with a logo for his side; at an appropriate moment, they tore open their shirts to reveal the logos. The late Bennett Cohen, a professor of veterinary medicine, used slides of animals from his research, with altered captions, to show the allegedly dire effects of whichever food he was against.

Rabbi Robert Dobrusin used biblical arguments to show that the fruit involved in Adam and Eve's fall was really a potato. Rabbi Robert Levy took off his rabbinical robes to reveal a green doctor's coat and offered medical charts that, he claimed, proved hamantaschen were healthier. Surgeon Lazar Greenfield warned that humans have a "grease gland" that could be activated by eating too many latkes, and Lana Pollack, then a state senator, read a Michigan Senate resolution proclaiming that the latke was best.

Chuck Newman ran a negative campaign—"I juggled a latke, showing how it fell apart," he recalls. He also demonstrated how oily the latke was by putting one in a balloon and squeezing out the oil. "But I was faking, because it had oil in it already," he admits.

After a chance for rebuttal and questions from the audience, a vote was taken. The side that received the loudest applause won. The debaters and audience would then adjourn for refreshments—latkes and hamantaschen.

—Grace Shackman

ILLUSTRATION BY WENDY HARLESS