Willow Run's Glory Days

During World War II, the Ypsilanti factory became a worldwide symbol of American industrial might. To get it built, Charlie Sorensen had to overcome red tape from Washington, skepticism from the aircraft industry, and his own quixotic boss, Henry Ford.

Ann Arbor High senior Don Exinger spent the summer of 1941 working on a farm east of Ypsilanti. Named Camp Willow Run, after the creek that wound through its woods and gently rolling fields, it belonged to auto pioneer Henry Ford. Ford was determined to instill his own work ethic in the teenaged campers: they slept in army tents and were roused at 5:30 a.m. to attend church services before breakfast and a hard day's work in the fields.

But even as Exinger's group planted and reaped, bulldozers were leveling Camp Willow Run's woodlot. By the next summer, the first of a corps of 50,000 factory workers were crowding out Ford's youthful campers. Two years after that, new B-24 Liberator bombers were pouring out of the Ford Willow Run plant at the rate of one each hour, headed for battle in the European or Pacific theaters.

Then, almost as quickly as it began, it was over: fifty years ago, on June 24, 1945, the farm-turned-factory completed its last bomber and halted production.

At the outbreak of World War II, Henry Ford was an elderly, unpredictable man riddled with contradictions. Decades earlier, he had been far ahead of his time in paying workers at the unheard-of rate of $5 a day. Now he was threatening to close down Ford Motor Company rather than accept workers' efforts to unionize. He was often spiteful toward his only son, Edsel, although he doted on his four grandchildren. At first loath to build weapons for a conflict he believed to be driven by a conspiracy of moneyed interests, he ended up as one of World War II's most prolific arms makers.

Ford abandoned his stand against the war when the Nazis swarmed across Europe in May 1940. But at first he insisted that his weapons be used only to defend the United States. In June, he vetoed a contract Edsel had negotiated to manufacture Rolls-Royce aircraft engines under license, because most of the engines were destined for England. A few months later, the elder Ford accepted a contract to build 4,000 Pratt & Whitney engines for U.S. aircraft.

In January 1941, Ford executives were invited to visit Consolidated Aircraft in San Diego, California, in the hope that the company might expand its involvement in aircraft production. Henry Ford had made it clear that he wasn't interested in collaborating with any aviation company, but Edsel made the fateful journey anyway, accompanied by Ford manufacturing boss Charles Sorensen.

Sorensen had begun his Ford career in 1905 as a $3-a-day pattern maker. The Danish immigrant was Hollywood-handsome, with a commanding presence, piercing blue eyes, and swept-back blond hair. Associates admired his quick mind as much as they feared his hot temper. Though little known compared to his publicity-hungry boss, Sorensen was Ford Motor Company's top manufacturing expert.

The Ford executives were polite to their hosts, but Sorensen in particular was unimpressed by the methods Consolidated was using to produce its B-24 Liberator bomber. There were no blueprints or accurate measuring tools. Major components were custom fit, so each plane was different from the next. Final assembly took place outside in the California sun. In his memoirs Sorensen observed sourly, "What I saw reminded me of the way we built cars at Ford 35 years earlier."

Sorensen knew that the assembly line method he had perfected in building more than thirty million Ford automobiles could easily eclipse Consolidated's modest goal of one airplane per day. When asked how he would manufacture the B-24, Sorensen replied confidently, "I'll have something for you tomorrow morning."

He wasn't kidding. He sequestered himself in his Coronado Hotel room, and by 4 a.m. the next day, he had sketched out the plan that became Willow Run. Working solely from figures he carried in his head, Sorensen estimated that it would take 100,000 workers and a $200 million plant to meet his goal of delivering one finished airplane every hour.

Over breakfast the next morning, Edsel Ford pledged his full support for Sorensen's bold stroke. George Mead, the government's director of procurement, was delighted, but Major Reuben Fleet, Consolidated's president, wasn't convinced. His counteroffer: a contract for Ford to build just 1,000 wing sections. Sorensen flatly replied, "We'll make the complete airplane or nothing."

Back home in Dearborn, Sorensen explained his scheme to Henry Ford. First he got an antiwar lecture, then a diatribe on how General Motors, the Du Fonts, and President Roosevelt were conspiring to drag the country into war and take over Ford's business. But in the end the cranky Henry agreed to the plan.

With little more than a letter of intent from the government, an army of Ford laborers set to work in a frenzy. Late in March 1941, 300 men with saws, axes, and bulldozers attacked the 100-acre woodlot where the plant would be situated. A steam-powered sawmill was brought in from Greenfield Village, Henry Ford's outdoor museum, to convert the felled trees to 400,000 board feet of lumber.

The fields were cleared for construction of the plant, designed by renowned Detroit architect Albert Kahn. Tool designers and other engineers were dispatched to San Diego to learn everything they could about building B-24's. Tool and die maker Martin Chapin traveled to San Diego with the first wave of 240 Ford personnel. "Consolidated had built and assembled aircraft for generations, and they thought our innovations were almost sacrilegious," he recalls, "They built airplanes with plumb bobs and levels, while we were used to sophisticated fixtures and gauges."

Ford engineers were particularly amazed by Consolidated's design fora landing-gear pivot. It was assembled out of half a dozen pieces of steel, a couple of large tubes, and some flat plates, all held together by nearly a hundred welds, each of which had to be X-rayed. Back in Dearborn, the inevitable conclusion was that Consolidated had never engineered the B-24 for high-volume production. Ford engineers reduced the landing-gear pivot to just three large castings.

Nine hundred men and women worked night and day seven days a week to design the critical tooling. More than 30,000 metal stamping dies—equivalent to eight or nine car model changeovers—were ultimately required to manufacture the bomber's 1,225,000 parts.

On April 18, 1941, five weeks after receiving an initial $3.4 million contract to build B-24 subassemblies, Ford broke ground for the plant. It was dedicated less than two months later, shortly before Henry Ford finally consented to the very first contract between the United Auto Workers and the Ford Motor Company. The last load of concrete for the adjoining mile-square airport was poured on December 4, three days before Pearl Harbor.

The harsh spotlights of publicity now shone on Willow Run. The sheer size of the facility was daunting. In his journal, Charles Lindbergh called Willow Run "a Grand Canyon of the mechanized world." With 2.5 million square feet of usable floor space, Willow Run had more aircraft manufacturing area than Consolidated, Douglas, and Boeing combined. The press extolled the sheer size of the undertaking without understanding that Willow Run still had to be equipped with effective tools and a functioning workforce. Production began in November 1941, but ten months passed before the first B-24 rolled off the mile-long assembly line. People began calling the plant "Willit Run?" prompting Senator Harry Truman to undertake a special investigation. According to a May 1943 article in Flying magazine, "The Truman Committee, which came to Detroit with blood in its eye, felt better after touring the plant and talking to Ford officials, and left with the pronouncement that 'Willow Run compares favorably with any other airplane plant in the country as far as actual production work is concerned—and we have seen them all.' "

Ted Heusel, then a teenager working in plant protection at Willow Run, remembers getting a call on Sunday morning from his boss, the infamous Harry Bennett, to help shepherd the Truman Committee around the factory. Ordinarily, Heusel's job was to listen in on phone calls made from the plant to watch for possible security leaks. The future WAAM radio host was just one of many Ann Arborites who found jobs at the plant. Based on interviews with people who lived in Ann Arbor during the war, it seems that anyone who didn't work at Willow Run themselves had a friend or family member who did.

Warren Staebler's uncle, Herman Staebler, co-owned the Pontiac dealership, but with car production halted for the duration of the war, he took an office job at Willow Run. Steve Filipiak, retired manager of WHRV (WAAM's forerunner), ran the factory's internal radio station, playing music, interviewing Truman and other distinguished visitors, and selling war bonds. Attorney John Hathaway remembers that almost everyone in his family worked at the plant. His sister Betsy was a long distance telephone operator in Harry Bennett's office. She sometimes drove to work with Ted Heusel. Hathaway's other sister, Mary, inspected hydraulic tubing, while her husband, Ned, worked in shipping and receiving. Hathaway's mother, Lucile Hathaway, identified and inventoried tools. "At Miller's Dairy Store, I had been working for 35 cents per hour," she wrote in an unpublished memoir. "When I drew my first pay at Willow Run I nearly fainted. We were working 9 hours per day and all day Saturday so that my pay at $1.10 per hour was really staggering."

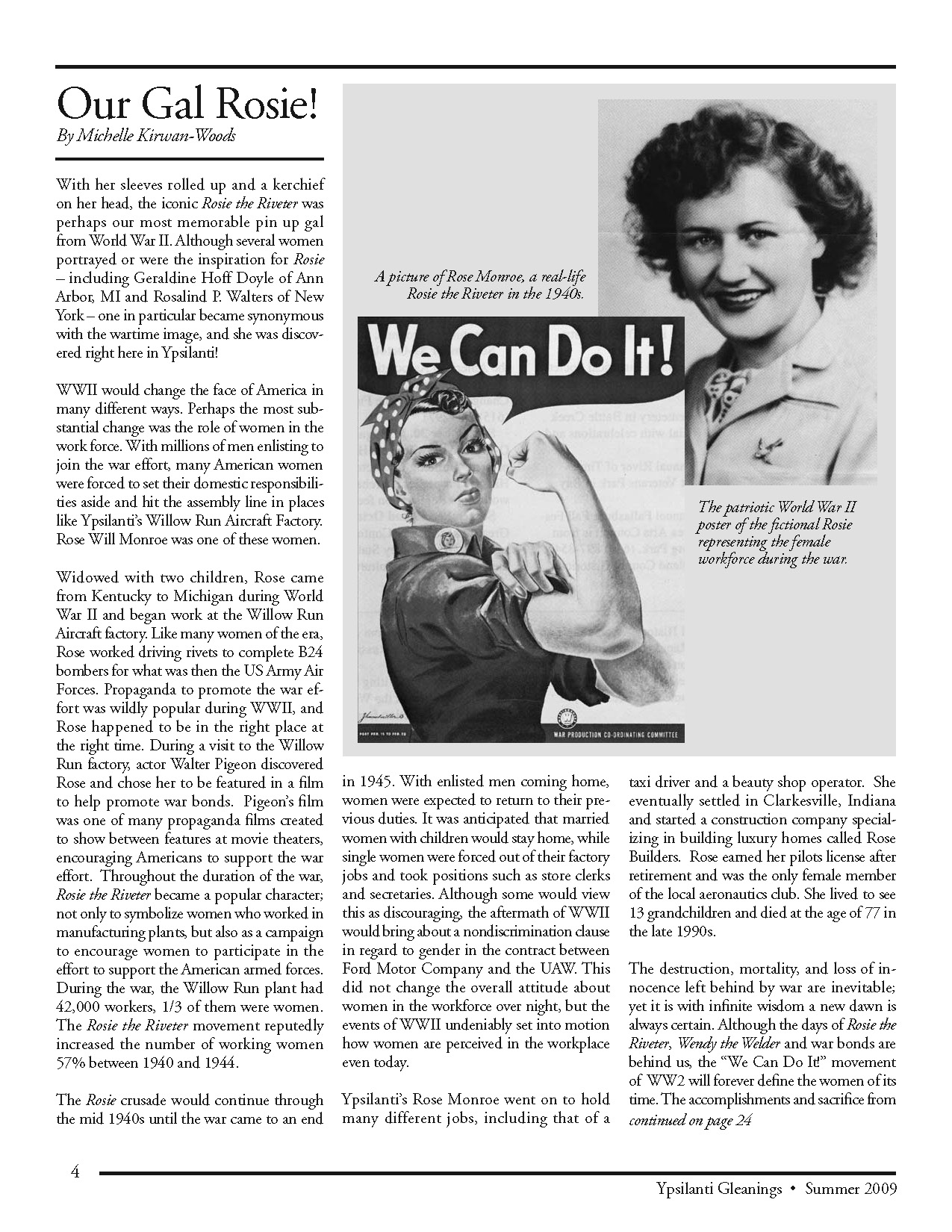

In all, more than 10,000 women worked at Willow Run. Anne Morrow Lindbergh lived in Bloomfield Hills while her husband, Charles, was helping Ford develop the planes. (Opinions differ on whether he was merely window dressing or an important advisor, but many report having seen him at the plant.) After a tour of Willow Run, Anne wrote in her diary, "One noticed chiefly the size, and the number of women working (they all looked like housewives—quite ordinary Middle Western housewives—not a new breed of 'modern women,' as I had expected ...)."

Flora Meyers worked first in fingerprinting (another wartime security measure) and then on the telephones—for instance, she'd call cleanup people when there were accidental spills. Johanna Wiese, retired assistant dean of the U-M School of Nursing, worked as a librarian in the Ford Airplane School, where new workers learned such skills as riveting. Betty Walters Robinson, although trained as a beautician, found herself working as a carpenter at Willow Run, hammering lids onto waterproof boxes that held replacement parts to be shipped to air bases all over the world.

Workers flooded in.from all forty-eight states, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Canada, and Latin America. John Hathaway, who bought his house from shoe store owners Fred and Gertrude Smith, remembers them saying that some of their customers had never worn shoes before and had to be taught how to walk in them. The late Art Schlanderer remembered bomber plant workers, many of them enjoying real money for the first time in their lives, coming to his jewelry store and making extravagant purchases, like diamond-studded watches. Helen Mast, who was running Mast's shoe store by herself while her husband, Walter, was in the service, sold hard-toed protective shoes to many women who worked at the plant.

By early 1942 there were no rental rooms to be found within a fifteen-mile radius of Willow Run. Resourceful landlords often collected double or even triple rent for rooms: while one tenant worked, the other slept. Many larger single-family homes in Ann Arbor were divided into rental rooms or apartments during this time. Warren Staebler's parents, Dora and Albert, rented a room to a Willow Run control tower operator. Fritz and Bertha Metzger, owners of the German Inn on Huron, rented rooms to four or five lucky people who for $11 a week got not only a bed but meals at the German Inn.

At first Henry Ford balked at building housing for Willow Run workers, but under federal pressure he finally relented. Guy Larcom, later Ann Arbor's city manager, came to Willow Run to work for the Public Housing Administration. The PHA erected an entire town—Willow Village—almost overnight, with dormitories for single workers and small houses for families. The first set of fifteen buildings, accommodating 3,000 people, opened early in 1943. A mobile home park that followed was promptly jammed with 1,000 trailer homes. Ramshackle prefab houses rolled in by the truckload. They were loaded with the floor sections on top and roofs on the bottom, and as a crane lifted the pieces off, workers nailed them up in speedy succession. Each house had a crude coal stove, and residents had to get by with iceboxes instead of refrigerators. They were the lucky ones: many workers lived in converted gas stations, shacks, or tents. By the end of 1943, when 42,331 employees worked at the plant, Willow Village was providing temporary shelter for 15,000—a population greater than the city of Ypsilanti's.

Gradually, Willow Run's production numbers began to mount: from a net output of fifty-six airplanes for all of 1942 (most of them assembled by Consolidated and Douglas, in Oklahoma and Texas) to thirty-one airplanes in January 1943 and 190 in June. By March 1944—shortly after Charlie Sorensen was pressured into resigning from Ford in a power struggle—Willow Run realized his dream, producing 453 airplanes in 468 working hours. Willow Run's output nearly equaled the entire airplane production of Japan that year. Ford's efficient assembly line methods led to a remarkable drop in the delivered price of a B-24: from $238,000 in 1942 to $137,000 in 1944. In all, 8,685 B-24's were built at Willow Run before the last contract expired in June 1945—including 1,894 knocked-down kits shipped to other plants for assembly.

After the war ended, Ford chose not exercise its option to buy Willow Run from the government. The airport served as southeast Michigan's main passenger airport until the late 1950's when all the main carriers moved to Detroit Metro. The plant was sold to Kaiser-Fraser for production of automobiles (and, later, of C-119 cargo planes). General Motors acquired the facility in 1953 after fire ravaged its Hydra-Matic transmission plant in Livonia. After a frantic twelve-week conversion, GM began making automatic transmissions at Willow Run and continues making them there to this day. Some of the overhead cranes and hangar doors installed by Ford more than fifty years ago are still in regular use.