Expected Greatness: UMMA's "The Power Family Program for Inuit Art: Tillirnanngittuq" shows Ann Arbor's role in popularizing indigenous Arctic art

The influx of Inuit art in Ann Arbor began with Ann Arbor’s Eugene Power and Canadian artist James Houston. Power, a friend of Houston, became interested in the art and culture of Inuit peoples following his friend Houston’s research there, beginning in 1948. A decade later, Eugene Power and his son Philip founded a non-profit organization called Eskimo Art Inc. in Ann Arbor that operated as a wholesale distribution center for artworks imported from Kinngait (known then as Cape Dorset) Hudson Bay and Baffin Island. The organization sent profits to artists, funded art supplies, and organized artist training, including Japanese printmaking techniques. Inuit art continued to remain popular in the area, with Eskimo Art Inc. remaining open through 1994.

The Power Family Program for Inuit Art: Tillirnanngittuq exhibition includes many works that date to the beginning of the Power Family’s involvement with Inuit art and the subsequent creation of Eskimo Art Inc. Currently being shown at the University of Michigan Museum of Arts, the exhibition “celebrat[es] the exceptional gift of 20th-century Inuit art to the Museum by the Power family.” The exhibit features 58 works from the collection, which were promised as a gift to the museum in 2018. The title of the exhibition, Tillirnanngittuq, is the Inuktitut word for “unexpected,” referencing the tremendously positive public response to Canadian Inuit Art in Ann Arbor, and globally, beginning in the mid-20th century.

The collection was most recently owned by Philip and Kathy Power, and most of the work is from the early period of export, created in the 1950s to 1960s. The exhibit includes prints made with stonecut and stencil techniques, and sculptures carved from ivory, bone, and stone. Seven of the 24 prints are from the first annual print collection in 1959. Collections like these are valuable resources, and UMMA notes that “the exhibition also serves as a promising launch pad for future groundbreaking research, exhibitions, and programming related to Inuit art and culture at the University of Michigan, thanks to the generosity of the Power family.” The Power family plays a central role in the two stories traced by the exhibit. The first story is that of the Power family, which played a prominent role in introducing Inuit art not only to Ann Arbor but to a broad U.S. audience. The second is the development of Inuit art techniques that lead to Inuit art’s “subsequent worldwide acclaim.”

The exhibition explores the history and developments that lead to the distribution and consumption of Inuit art. The gallery texts offer insight into the historical forces that shaped the production and sale of art. Before the 1950s, the Inuits maintained their livelihood through hunting. A few things happened that changed the way of life, from the shift in migration patterns of Arctic animals to the collapse of fur trade (white fox, specifically), and the introduction of disease by whalers and traders up to that point. Inuit peoples became a focus of the Canadian federal government when administration posts were created in the Arctic to “provide health, education, and other services to the Inuit.” This coincided with a decrease in the availability of natural resources to sustain the traditional Inuit way of life, forcing them to rely on other means to provide for themselves. One of these means became the exportation of sculpture, which the Inuit traditionally created from ivory. James Houston encouraged the use of soapstone, an element readily available in the environment. Over time, soapstone became a primary medium for Inuit sculptors, with ivory being used for adornment and decorative elements. After the 1950s, Inuit art was impacted by increased availability in materials and techniques. Previously, whalers had exchanged goods with the Inuit people, but it was not until the 1950s that paper was introduced. Using drawing skills that had previously been carried out with incising techniques on ivory, artists began drawing.

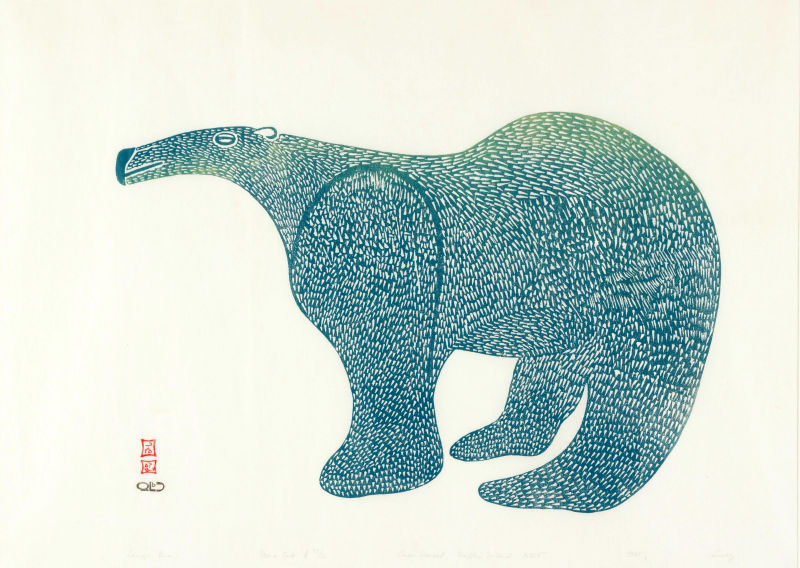

Niviaksiak, Polar Bear and Cub in Ice, Cape Dorset, 1959, stencil. Promised gift of Philip and Kathy Power. © Dorset Fine Arts. Photography: Charlie Edwards

In 1957, printmaking experiments were introduced at Kinngait (Cape Dorset) when James Houston gave a demonstration to local artists. Sculptor Osuitok Ipellie was enthusiastic about the process and was eager to adapt it for use with Inuit imagery. Shortly after, the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, a locally owned and managed organization, began releasing annual print collections at Kinngait Studios, also known as Cape Dorset Graphics, which provided the artwork for the annual shows beginning at the Stratford Festival in Ontario in 1959. Houston also worked with organizations such as the Canadian Guild of Crafts, Hudson’s Bay Company, and Power’s Eskimo Art Inc. to promote Inuit art in the United States and Canada.

The stoneblock printmaking technique was employed by many artists represented in the exhibition. One such artist was Lucy Quinnuayuak, whose print Goose Fighting for Fish is displayed above the carved stone block from which the prints were pulled.

The most recently-created artwork on display in the gallery is the work by artist Saila Kipanik, titled Two Narwhals, 2012. Narwhals play an important role in Inuit mythology. The legend says the Narwhal was once a woman. The woman had long hair that she twisted into a single braid. The woman had a daughter and a stepson, but she was cruel to the son, who was blind. After the woman tricks him, her stepson claims revenge on his stepmother by tying her to a beluga whale. She and the whale disappear, merging together and turning into the narwhal, her braid becoming the narwhal’s tusk.

Some of the renowned Inuit artists featured at UMMA are Kenojuak Ashevak, Niviaksiak, Osuitok Ipeelee, Kananginak Pootoogook, and Johnny Inukpuk.

UMMA’s wall text summarizes the success of Inuit art, saying: “Seventy years ago, neither the Inuit artists nor the Power family could have foreseen the tremendous popularity that this work would come to enjoy,” and “in less than a generation, contemporary Inuit art was recognized worldwide for its artistic excellence and became a stable source of income for the Inuit.” Now, UMMA will have an important resource for future artists and historians. Through the current exhibition, it is clear that many more than two stories can be told from the collection.

Elizabeth Smith is an AADL staff member and is interested in art history and visual culture.

"The Power Family Program for Inuit Art: Tillirnanngittuq" is on display 3/19-10/6 at UMMA. Curated by Marion “Mame” Jackson in collaboration with Patricia Feheley.