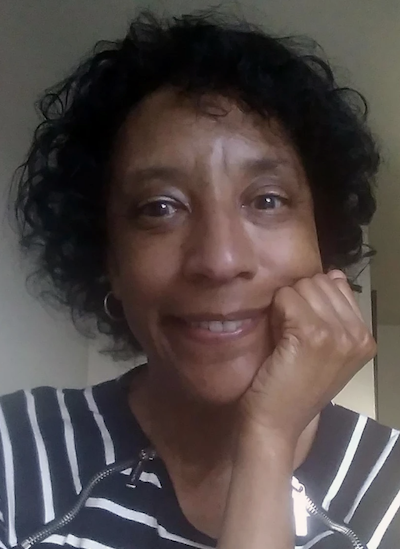

AADL Talks To: Bev Willis

When: June 22, 2023

Bev Willis is an Ann Arbor historian who has worked with several historical organizations, including the African American Cultural and Historical Museum, the city’s Historic District Commission, and the Washtenaw County Historical Society’s Museum on Main Street. Bev talks with us about her passion for local history and the mentors, family members, and cultural influences that helped chart the course of her career.

Washtenaw County Historical Society's Museum on Main Street

African American Cultural and Historical Museum

Media

June 22, 2023

Length: 00:42:34

Copyright: Creative Commons (Attribution, Non-Commercial, Share-alike)

Rights Held by: Ann Arbor District Library

Downloads

Subjects

Museum on Main Street

Washtenaw County Historical Society

Ann Arbor Historic District Commission

Black American Community

Old West Side

African American Cultural & Historical Museum of Washtenaw County

Black Americans

University of Michigan - Student Housing

Streets & Roads

House B

Black History

Historic Preservation

Museums

Beverly Willis

Louisa Pieper

Coleman Jewett

Jill Thatcher

George Jewett

Ann Arbor 200